Standing and delivering The resolute Louis Riel-led armed resistance to protect Métis people, their land and language from Ottawa's ill intentions is woven into the fabric of Manitoba 150 years later

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/05/2020 (2033 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

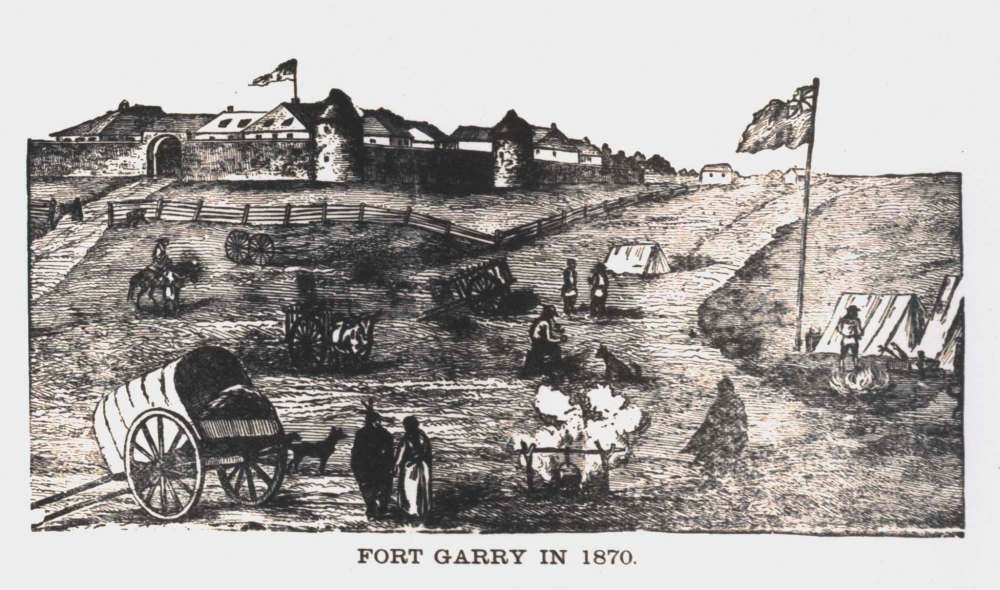

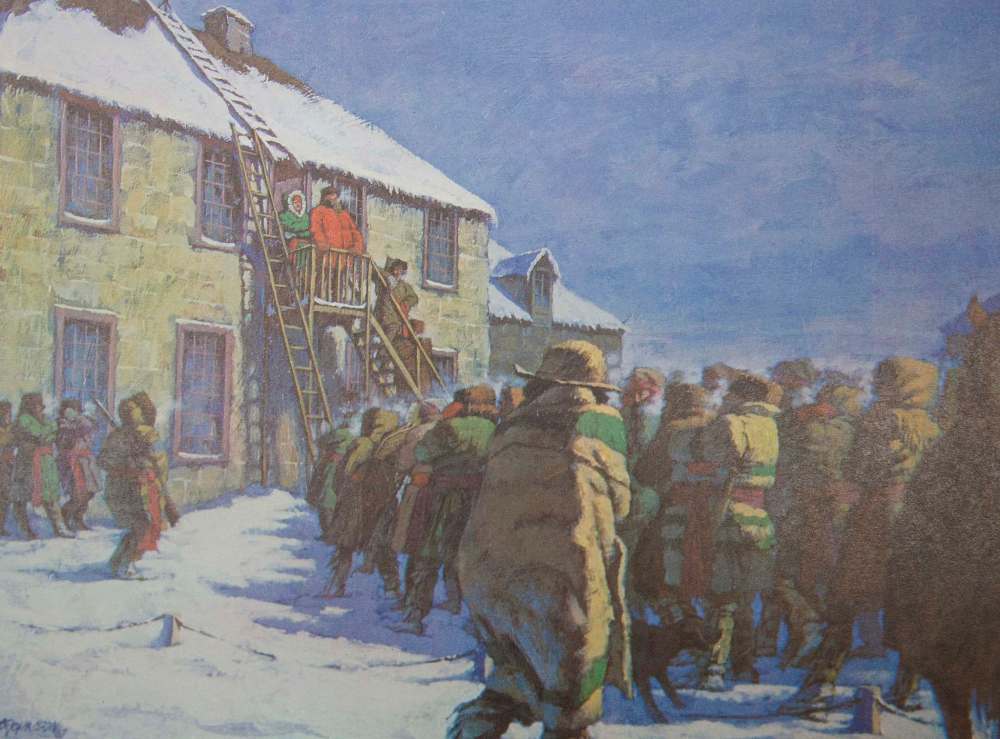

As Manitoba gets set to mark its 150th anniversary in 2020, the Free Press turns back the clock and takes an in-depth look at the dramatic story of how a small community living on the banks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers stood up to the federal government and demanded a say in the terms of joining Canada. The Red River Resistance of 1869-70 is a story of courage and determination by a group of Manitoba Métis who challenged a colonial mindset in Ottawa and took up arms to protect their democratic, cultural and legal rights.

It begins in October 1869 and culminates in the passage of the Manitoba Act by Parliament in May 1870 – a constitutional amendment that still serves today as the legal framework for Manitoba’s place in Canada. The following is the final instalment of a three-part series that follows the timeline of what unfolded in the Red River Settlement 150 years ago, and the events that led to Manitoba’s entry into Confederation.

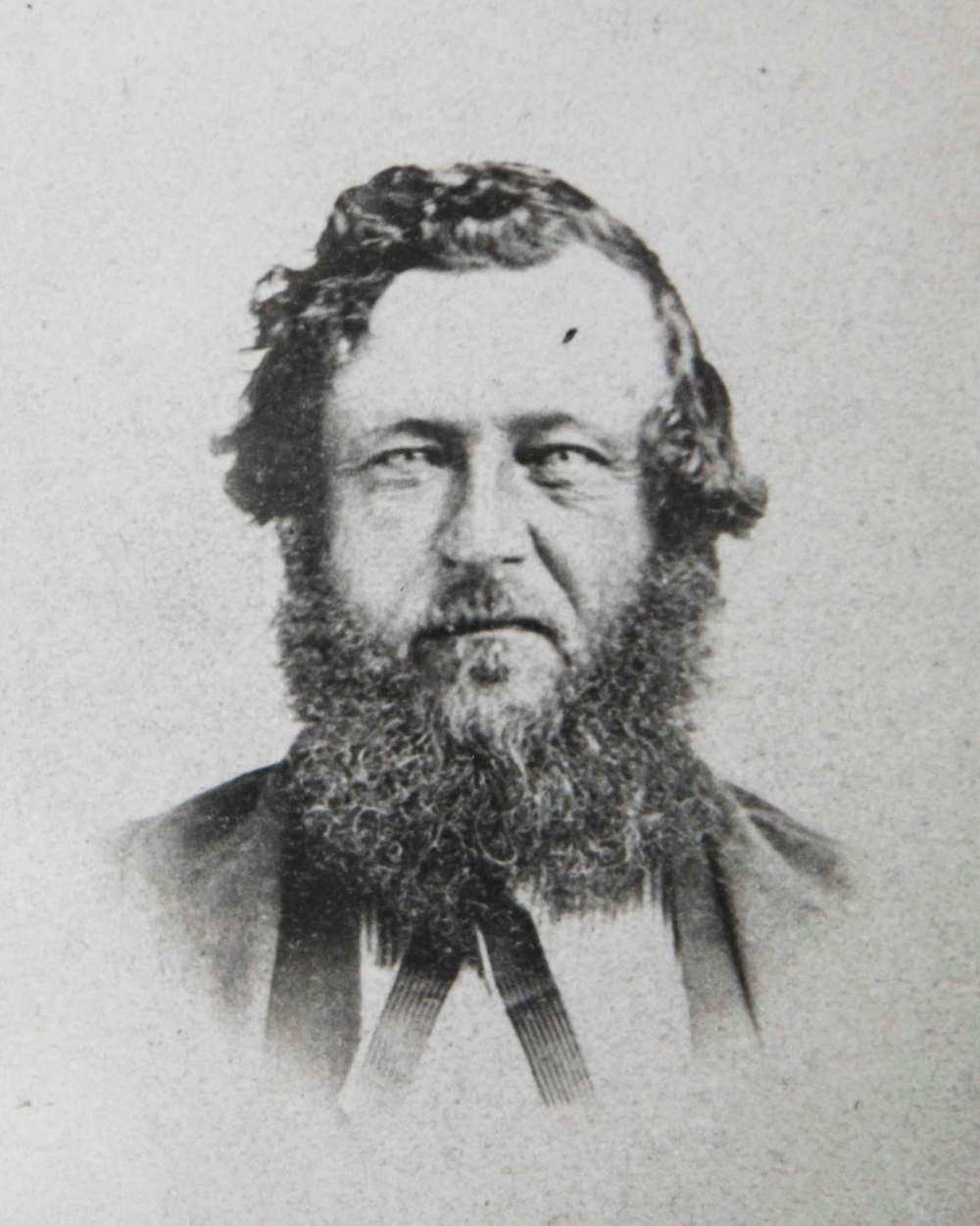

NOEL Joseph Ritchot had the most important job in the Red River settlement in the spring of 1870. The St. Norbert parish priest was about to go toe-to-toe with the most powerful politicians in Ottawa — John A. Macdonald, Canada’s prime minister, and his right-hand man, George Étienne Cartier, the federal minister of militia and defence.

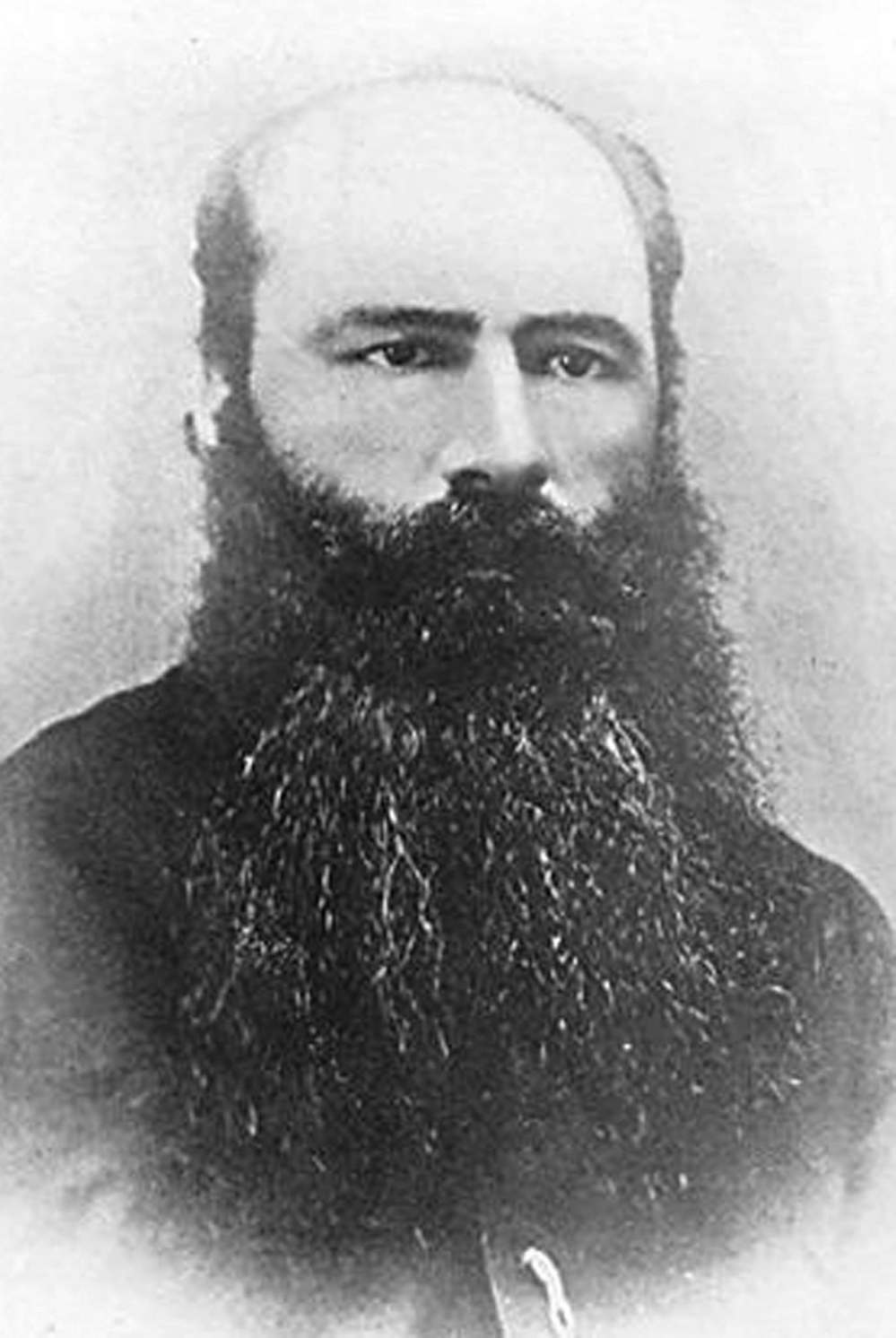

Ritchot, a French-Canadian who moved to Red River in 1862, was one of three delegates chosen by the provisional government at Upper Fort Garry to negotiate the terms of Manitoba’s entry into Confederation. He spoke no English and had no real experience in politics, much less a background in constitutional law. But the man with the long black beard, at age 45, found himself as the principal negotiator for the Red River settlement, more out of necessity than personal desire. Whether he knew it or not at the time, the fate of the settlement now rested on his shoulders.

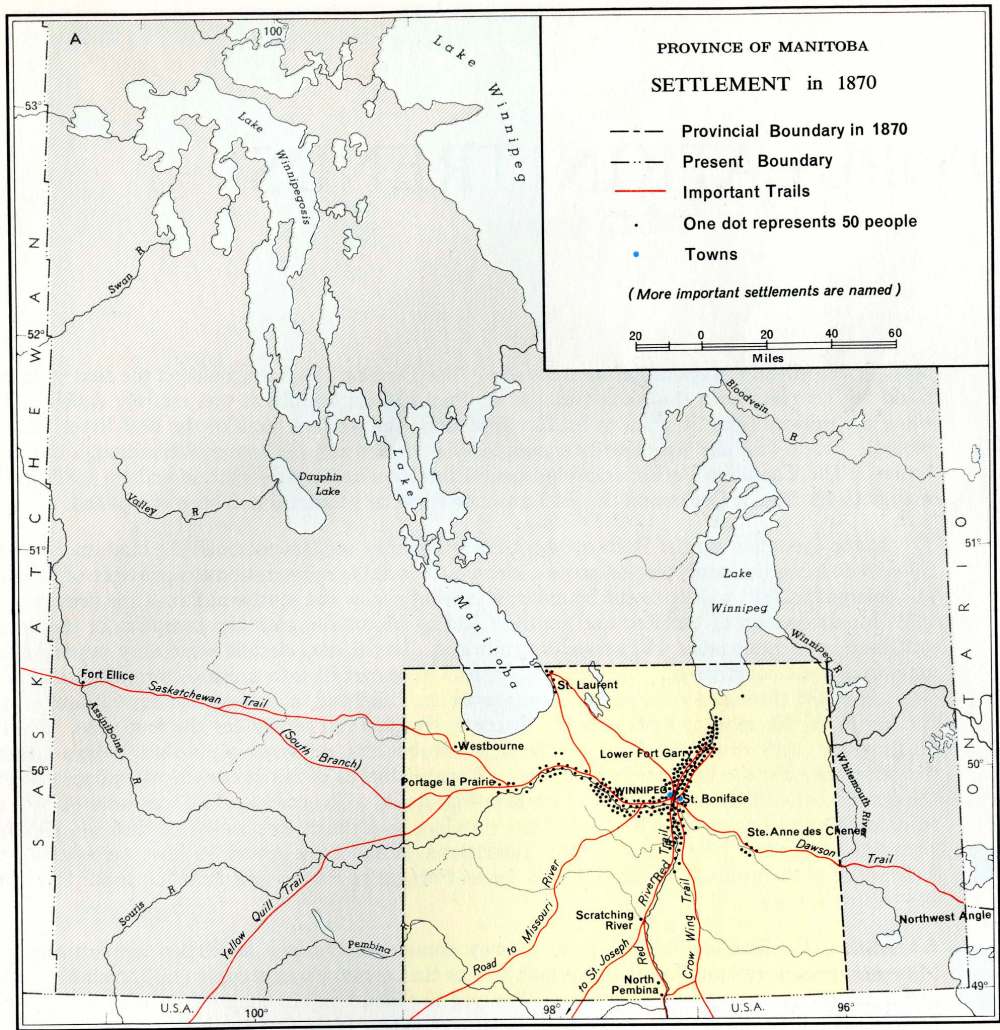

It had been five months since Métis leader Louis Riel and his supporters took a stand against Canada. Ottawa attempted a unilateral annexation of the settlement after striking a deal to purchase Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1869. Federal officials ran into a roadblock when the tiny community of some 12,000 traders, buffalo hunters, farmers, retailers, craftsmen and others (in what was then called the District of Assiniboia) demanded the protection of their democratic, linguistic and land rights before joining the fledgling dominion. The West wanted in, but not at any cost.

Ritchot played a key role in the early stages of the resistance, lending his moral support and guidance to the French Métis — many of whom were his parishioners. His influence helped legitimize the movement. He was an obvious choice as the delegate for the francophone Métis. Judge John Black, the head of the General Quarterly Court of Assiniboia, was chosen as the anglophone representative. Alfred Scott — a bartender and a store clerk in the village of Winnipeg — was the third delegate, selected to look out for the interests of the small group of Americans living in the community.

Ritchot was the clear leader among the delegates. The parish priest was chosen for his persistence, intellectual capacity and his loyalty to the Métis cause. He had no experience bartering with high-powered politicians. But his dogged determination (and a natural political skill set he probably didn’t know he had) made him a formidable opponent at the negotiating table.

Ritchot left for Ottawa March 23, 1870, in the company of Colonel Charles de Salaberry, one of the early emissaries sent to Red River by the federal government. The same week, the Globe newspaper in Toronto carried a front-page story of the March 4 killing of Thomas Scott, the Canadian “loyalist” twice jailed by Riel and the Métis and executed by firing squad outside the walls of Upper Fort Garry. It was an early sign of the political hornet’s nest the Red River negotiating team was about to enter.

After meeting up with his fellow delegates in St. Cloud, Minn., Ritchot began the journey to Ottawa by train. John Black travelled through Detroit to Toronto, then on to Ottawa. Ritchot and Alfred Scott, wary of the political troubles awaiting them in Toronto after being tipped off, took a more clandestine route. They headed to Buffalo and met up with Gilbert McMicken of the Dominion Police at Ogdensburg, N.Y., who escorted them safely to Ottawa April 11. The federal government, aware of a growing Riel backlash in Ontario, not only sought the safe passage of the delegates to Ottawa, they made every effort to keep talks as low-key as possible.

Almost immediately upon arrival in Ottawa, Scott — and later Ritchot — were arrested by local police. Any diplomatic immunity they thought they enjoyed as official delegates from Red River was dashed. Warrants for their arrest were sworn out by members of Canada First, a small but influential group of anti-French and anti-Catholic populists in Ontario. John Christian Schultz, who had been jailed by Riel in Red River after leading a counter-resistance against the Métis, was a member of the group. He and others travelled to Ontario prior to the arrival of the delegates. They spent days whipping up anti-Riel sentiment, organizing large public rallies in and around Toronto and calling for the immediate cancellation of talks between Ottawa and the “murderers” of Red River. They demanded justice for the death of Thomas Scott.

Ritchot and Alfred Scott were twice arrested on charges of complicity for Scott’s killing. But their legal troubles didn’t last long. After a few days of house arrest, the courts declared the warrants invalid and the delegates were free to resume their diplomatic responsibilities. Meanwhile, the third delegate, John Black, arrived in Ottawa unmolested. This wasn’t the kind of welcome Ritchot and his colleagues had expected.

● ● ●

John A. Macdonald had some choppy political waters to navigate in April 1870. Canada First and its supporters proved to be a thorn in his side. Macdonald didn’t want to appear overly sympathetic to Riel and the Métis. He wanted to avoid alienating Ontario voters. But he also had Quebec supporters, including the francophone wing of his caucus — who were more supportive of the Métis cause — to placate. The resistance had been widely reported in Ontario and Quebec newspapers over the winter and divisions were forming along linguistic and religious lines.

Underlying that was a demand by the British government that Ottawa negotiate a fair settlement with the Red River delegation. When Ritchot and Scott were arrested, the British government immediately cabled federal officials and asked if they had approved the warrants; they had not. (The federal government, in fact, provided the delegates with legal resources).

Key players

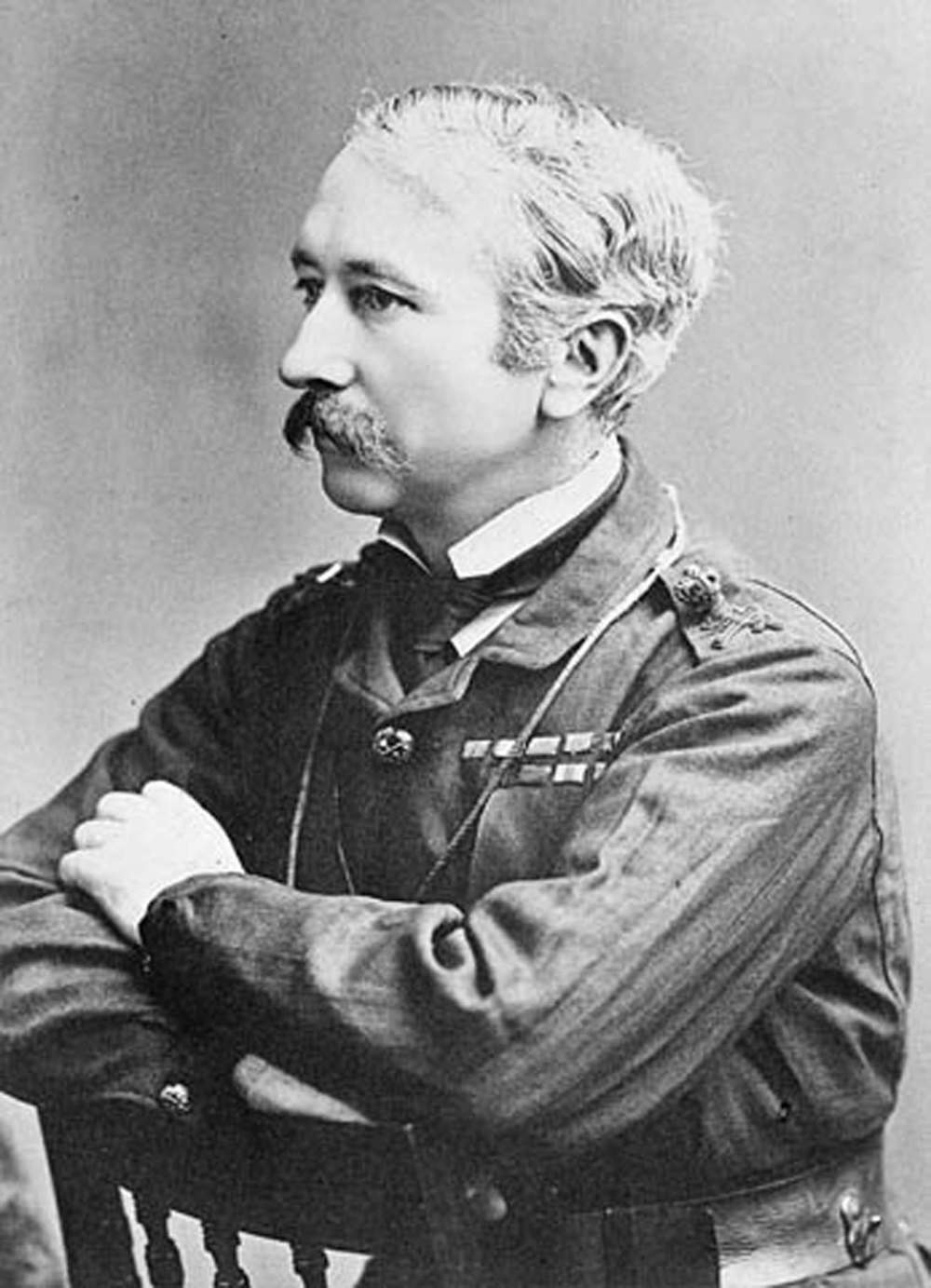

Col. Garnet Wolseley: Field commander of the military expedition sent to Red River in 1870. Wolseley led the British 60th Rifles and two volunteer Canadian militias on a three-month trek through the wilderness from Lake Superior to Upper Fort Garry. Wolseley’s troops arrived in Winnipeg by boat via Lake Winnipeg and the Red River. Despite a pledge the expedition would be a peaceful one, Wolseley would later write of disappointment troops faced no armed resistance from Red River residents (and of having lost the opportunity to “hang” Métis leader Louis Riel). Some of the soldiers under his command were openly hostile towards Métis residents.

Col. Garnet Wolseley: Field commander of the military expedition sent to Red River in 1870. Wolseley led the British 60th Rifles and two volunteer Canadian militias on a three-month trek through the wilderness from Lake Superior to Upper Fort Garry. Wolseley’s troops arrived in Winnipeg by boat via Lake Winnipeg and the Red River. Despite a pledge the expedition would be a peaceful one, Wolseley would later write of disappointment troops faced no armed resistance from Red River residents (and of having lost the opportunity to “hang” Métis leader Louis Riel). Some of the soldiers under his command were openly hostile towards Métis residents.

Noel Joseph Ritchot: The St. Norbert parish priest helped the French Métis organize the resistance in the fall of 1869. He was among three appointed delegates from Red River that travelled to Ottawa in April 1870 to negotiate the terms of the Manitoba Act with the federal government. Ritchot was the principal negotiator and succeeded in securing land rights for the children of Métis families.

Judge John Black: Recorder and president of the General Quarterly Court of Assiniboine (Red River’s top court until 1870), Black was one of three delegates sent to Ottawa. He was a member of the Council of Assiniboia and an English representative on the Convention of Forty (formed in January 1869 to set out the terms of Red River’s entry into Canada). Black spoke against initial provincial status for Manitoba during Convention of Forty talks, but didn’t oppose it as a delegate in Ottawa.

Alfred Scott: A bartender and store clerk in Red River, Scott was the third delegate appointed to attend negotiations in Ottawa. He represented the small contingent of Americans in the settlement.

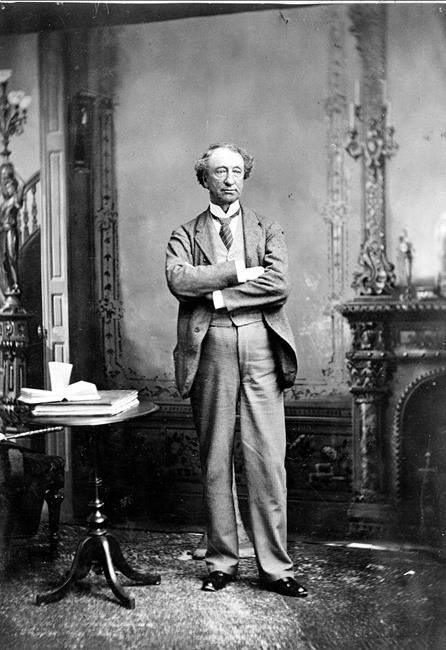

John A. Macdonald: Canada’s prime minister in 1870. He introduced the Manitoba Act in the House of Commons and spoke in favour of it. Macdonald was directly involved in negotiations with the delegates from Red River, although he was not present for much of it due to illness and “incapacitation.” He initially sought territorial status for Manitoba with an appointed council, but eventually agreed to provincial status and a democratically elected government. Macdonald began organizing a military expedition to Red River prior to negotiations with delegates.

George Étienne Cartier: A senior member of federal cabinet and principal negotiator with Red River delegates. Cartier, an influential French-Canadian representative of government and a Father of Confederation, was Macdonald’s right-hand man. He was sympathetic to the French Métis cause. However, his verbal commitments of immunity against prosecution for those involved in the resistance never materialized.

Macdonald had a problem on his hands. He had, for months, been secretly organizing a military expedition to Red River and needed British support. No matter the outcome of negotiations, Ottawa planned to send troops to Red River to assert Canada’s authority in the West. But the prime minster wanted a British battalion to lead the campaign as Canada didn’t have regular troops in 1870. London would agree only if the federal government concluded successful negotiations with the delegates. The British government didn’t want Canada to assume control of the northwest through military force. It was a quid pro quo Ritchot wasn’t aware of at the time. Had he known, it would have given him greater leverage at the bargaining table. Nevertheless, with the British government breathing down his neck, Macdonald was motivated to conclude a deal.

It took two weeks after the arrival of the delegation for talks to begin, a delay Ritchot wasn’t pleased with. While both Macdonald and his lieutenant George Étienne Cartier did the bargaining for Canada, it was Cartier who emerged as government’s chief negotiator. Macdonald was twice absent from talks, once because he was “indisposed” (one of his many bouts with the bottle) and again when he became seriously ill.

Ritchot found an ally in Cartier. The Quebec-born politician — himself involved in a resistance earlier in his life during the rebellion of 1837, where he fought for responsible government — was sympathetic to the Métis cause. Negotiations took place in Cartier’s Ottawa home, away from the prying eyes of newspaper reporters and others. It was there Ritchot and Cartier developed a friendly relationship. Both men spoke French and shared similar cultural backgrounds. Ritchot was often invited for dinner at Cartier’s home.

Still, the two sides were far apart in the early stages of negotiations. Macdonald and Cartier immediately tested the will of their rookie counterparts. They initially refused to even recognize the delegates as official representatives of Red River, proposing instead to hold informal discussions. It wasn’t until Ritchot threatened to return to Red River that Macdonald and Cartier agreed to acknowledge them — in writing — as formal representatives of the Northwest.

Negotiations began in earnest April 25 and both sides bargained hard. Macdonald wanted the settlement to enter Canada as a territory governed by a lieutenant-governor and an appointed council. He argued it would be a temporary measure followed by representative government and provincial status sometime in the future. The motivation was obvious: wait until the settlement is flooded with easterners before allowing people to vote and run for office.

The delegates insisted on immediate provincial status — a key demand of Riel — and an elected legislative assembly. Macdonald proposed a hybrid; half elected, half appointed. The delegates would have none of it, a position they stuck to and won. The settlement would enter Canada with full provincial status, governed by an elected legislative assembly and a senate. The delegates won Round 1.

The new province would also get representation in Parliament — four seats in the House of Commons and two in the Senate. Ritchot demanded, and won, the use of French and English in the provincial legislature and the courts. Denominational schools would be enshrined in law. And on Riel’s recommendation (after writing Ritchot in April and proposing the names “Manitoba” or “North-West”), the new province would be called Manitoba.

There were plenty of compromises the delegates had to accept. Ottawa insisted on maintaining control of Crown lands, not only within the province, but outside of it, too. The boundaries of the province would be severely limited. Ottawa wasn’t about to hand over the entire land mass of the Northwest territories (which was bigger than either Ontario or Quebec at the time) to 12,000 people living in a small, isolated community. The federal government had bigger plans in store, including the construction of a Pacific railway as part of its vision to settle the West. They needed access to Crown lands to accomplish that.

Manitoba got provincial status, but its geographical size would be small; not much bigger than what was then known as the District of Assiniboia, a 50-mile radius around Upper Fort Garry. The “postage stamp” province would span about 11,000 square miles. (Manitoba’s boundaries grew to its current size in 1912).

There were many battles over land rights during negotiations, including how land holdings would be recognized. Some of the provisions agreed to were later changed unilaterally by federal officials during the legislative process, throwing Ritchot into a fit of anger. Of most concern to him, though, was ensuring Métis land rights were protected. Ottawa initially balked at the notion of recognizing Indigenous land rights while granting “civilized government” to the Métis. They argued the Métis couldn’t have it both ways — a 19th century colonial mentality that coloured much of the talks. Eventually, a middle ground was found. The federal government offered the Métis 100,000 acres, an amount Ritchot was able to increase to 1.4-million acres, to be granted to the children of Métis families.

1870 Timeline

April 11: Red River delegates Noel Joseph Ritchot and Alfred Scott arrive in Ottawa for negotiations with the federal government

April 12: Alfred Scott and, later, Ritchot, are arrested on a Toronto warrant for complicity in the murder of Thomas Scott. After release and a second arrest, warrants are dismissed by an Ontario court for both delegates. Third delegate Judge John Black later arrives in Ottawa without incident.

April 11: Red River delegates Noel Joseph Ritchot and Alfred Scott arrive in Ottawa for negotiations with the federal government

April 12: Alfred Scott and, later, Ritchot, are arrested on a Toronto warrant for complicity in the murder of Thomas Scott. After release and a second arrest, warrants are dismissed by an Ontario court for both delegates. Third delegate Judge John Black later arrives in Ottawa without incident.

April 25: First meeting between the delegates and prime minister John A. Macdonald and George Étienne Cartier at the latter’s home. Negotiations last four days.

May 2: John A. Macdonald introduces the Manitoba Act in the House of Commons for first reading. Explains the name “Manitoba” has been chosen for the new province.

May 9: Manitoba Act passes third reading 120-11

May 12: Manitoba Act receives royal assent.

May 14: Ritchot telegraphs Red River, reports negotiations concluded “satisfactorily.”

May 21 – Col. Garnett Wolseley, field commander for the military expedition to Red River, leaves Collingwood, Ont. Troops — including British soldiers and two Canadian volunteer militia — follow in subsequent days for the three-month trek to Manitoba.

May 27: Text of Manitoba Act published in Red River newspaper the New Nation

June 17: Ritchot, travelling through the United States, arrives back in Red River on the steamboat the International to a 21-gun salute

June 24: Legislative assembly in Red River approves Manitoba Act unanimously.

July 15: Manitoba Act proclaimed into law by federal government.

July 31: Wolseley arrives in Fort Frances.

Aug. 20: Battle-ready British troops arrive at Fort Alexander. Canadian militia follows several days behind.

Aug. 22: Troops arrive at the mouth of the Red River.

Aug. 24: Métis leader Louis Riel, realizing he was deceived by Ottawa that Wolseley’s expedition would be a peaceful one, bolts from Upper Fort Garry, crosses Red River to St. Boniface. Troops enter Fort Garry, ransack parts of it.

Sept. 2: Manitoba’s first lieutenant-governor Adams Archibald arrives in Red River.

Sept 10: Wolseley departs Red River; leaves behind Canadian militia to “police” the settlement.

How that land would be distributed became the subject of great debate and years of controversy after 1870. Ottawa promised the land grants would be administered through a local committee. But like many of their verbal promises, federal officials reneged on that. (The land distribution issue was the subject of a landmark Supreme Court of Canada decision 143 years later).

Negotiations were intense. They lasted four days and concluded on April 28. A draft bill of the Manitoba Act was given to Ritchot, who pored over it line by line, marking it up with proposed changes and question marks. It was brought back to the negotiating table for further revision.

Macdonald introduced the bill in the House of Commons on May 2 (although it wasn’t distributed to MPs until two days later). He announced that to honour the original inhabitants of the land “it is considered proper that the province which is to be organized shall be called Manitoba.” The name, he explained, was a “euphonious” Indigenous word meaning “The God who speaks — the speaking of God.”

It was a historic moment, one Ritchot surely savoured as he witnessed the introduction of the bill from the public gallery. But the fiery, sometimes ugly, Commons debate that followed was also sobering for Ritchot, who, along with others from Red River, became the subject of personal attacks from some MPs. Not all MPs were in agreement with the bill. Some had reservations about the Riel-led resistance and the legitimacy of the delegates sent from Red River.

During debate, MP William McDougall, the former lieutenant-governor designate who was refused entry into Red River six months earlier, called those who participated in the resistance “the most disreputable inhabitants of the country” who were “collected together by a bar room loafer.”

It’s unclear if he was referring to Riel (odd, since the Métis leader was neither a drinker nor a frequenter of saloons). But it triggered a lengthy and nasty sparring match between McDougall and Nova Scotia MP Joseph Howe, the government’s secretary of state for the provinces.

Opposition leader Alexander Mackenzie ridiculed the new province’s puny size. He said it “seemed ludicrous” to grant a “little municipality” like Red River provincial status and quipped that it reminded him of the story of Gulliver’s Travels.

Opposition members proposed a number of changes to the bill (including an attempt to remove the land grant provision for Métis families). But most were defeated.

There were some constructive developments during debate. Portage la Prairie, not part of Manitoba in the original bill, was added to the boundaries at second reading after concerns were raised about its exclusion. Portage, located just west of Winnipeg, was made up largely of English-speaking Canadians at the time.

After 10 days of heated debate, the bill — a constitutional amendment — was approved and given royal assent on May 12, a date now celebrated as Manitoba Day. The bill was proclaimed into law July 15.

The amnesty issue became a legal quagmire that dragged on for years. It was a major part of a House of Commons select committee inquiry held in 1874 into the “causes and difficulties in the North-West Territories in 1869-70.”

Ritchot wired Riel to inform him of the good news. Negotiations were completed “satisfactorily” and the Manitoba Act had passed, he wrote. The Red River community got its first look at the legislation May 27, when it was published in the local newspaper the New Nation.

There was still one outstanding issue, though. When negotiations began, Ritchot insisted (on instructions from Riel and the provisional government) that a general amnesty be granted as a condition of any settlement. They wanted an assurance in writing they wouldn’t be prosecuted for actions taken during the fall and winter of 1869-70, including the execution of Scott. However, federal officials argued they had no authority to issue an amnesty. Canada had no jurisdiction over Red River during the resistance. The granting of immunity would have to come from Britain, they said.

The amnesty issue became a legal quagmire that dragged on for years. It was a major part of a House of Commons select committee inquiry held in 1874 into the “causes and difficulties in the North-West Territories in 1869-70.” It was never satisfactorily resolved. Métis Ambroise Lépine, the adjutant-general in the provisional government who presided over the court martial of Thomas Scott, was tried for his death in 1873. Lépine was found guilty and sentenced to death, although his sentence was later commuted. Riel was never tried for Scott’s execution because he remained largely in exile after Manitoba joined Canada.

Alfred Scott and John Black left Ottawa after the passage of the Manitoba Act. Ritchot stayed and continued to lobby Cartier for an amnesty agreement. The best he could get was a verbal assurance that one would eventually come from England. It never did.

His job complete, Ritchot returned to Red River and arrived home via the steamboat the International on June 17. He was welcomed in Winnipeg with a 21-gun salute and greeted personally by Riel. All were anxious for a full briefing of what transpired over the previous two months.

On June 24, eight months after Riel and others prevented federal agents from surveying lands around Red River, the Manitoba Act was formally presented to the legislative assembly and approved unanimously. Local historian Alexander Begg marked the day in his journal as “the turning point in the affairs of the settlement,” celebrated that night with drink and merriment by members of the legislative assembly.

Riel and his provisional government didn’t get everything they wanted from Ottawa in their struggle for self-determination. The question of amnesty still hung in the balance. Years of delay and bureaucratic bungling by the federal government on land distribution proved damaging to the Métis community. Canadians flooded the new province almost immediately after Manitoba entered Confederation and snapped up valuable land. Many Métis families moved west.

Nevertheless, the decision to take up arms to protect their democratic, linguistic and land rights resulted in some level of legal protection for the people of Red River. To a large degree, their actions were vindicated. No matter how one interprets the events of 1869-70, they shaped Manitoba as we know it today.

tom.brodbeck@freepress.mb.ca

Tom has been covering Manitoba politics since the early 1990s and joined the Winnipeg Free Press news team in 2019.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Thursday, May 21, 2020 11:30 AM CDT: Photo removed.

Updated on Thursday, May 21, 2020 2:23 PM CDT: An incorrect image appeared in this story. The published image was of Rev. John Black, not Judge John Black. It has been removed.

![Thomas Scott (c. 1842 – 1870) was an Irish-born Canadian and fervent Orangeman. Scott was born in the Clandeboye area of County Down, in what is now Northern Ireland.[1] He was recruited by Canada to fight in the Red River Rebellion and was captured and imprisoned in Upper Fort Garry by Louis Riel and his men while trying to attack it along with 34 other volunteers. Scott made an attempt to escape but was recaptured by Riel's men and was summarily executed for committing insubordination. Scott's execution led to an outrage in Ontario, and was largely responsible for prompting the Wolseley Expedition, which forced Louis Riel, now branded a murderer, to flee the settlement. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Scott_%28Orangeman%29](https://dev.winnipegfreepress.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2022/05/Thomas+Scott.jpg?w=100)