Referendum requires a thoughtful vote

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

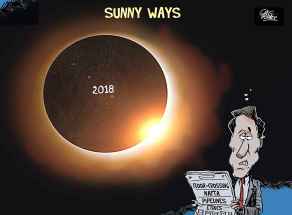

This article was published 20/09/2018 (2639 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

There’s a certain undefinable allure to participating in a referendum, such as the upcoming vote on whether Portage and Main should be opened to above-ground pedestrian crossings.

Voters will feel they are deciding something important, an enticing form of direct democracy, with citizens offering clear instruction to civic government. The result of the Oct. 24 referendum is not binding, but the candidates running for civic office will surely feel obligated to treat it as such.

Previous ballot questions

The last time the City of Winnipeg held a plebiscite was 1983. Here are the two questions voters were asked.

The last time the City of Winnipeg held a plebiscite was 1983. Here are the two questions voters were asked:

"Should the provincial government withdraw its proposed constitutional amendment and allow the Bilodeau case to proceed to be heard and decided by the Supreme Court of Canada on the validity of English-only laws passed by the legislature of Manitoba since 1890?"

The result: 76.49% of Winnipeggers voted “yes.”

"Do you support nuclear disarmament by all nations on a gradual basis with the ultimate goal of a world free of nuclear weapons and mandate the federal government to negotiate and implement with other governments steps leading to the earliest possible accomplishment of this goal?”

The result: 76.91% of voters supported disarmament.

Before 1983, the last city referendum was held in 1968, when voters agreed to allow commercial billiard halls to remain open on Sundays.

As well as empowering the public, referendums are sometimes seen as a way to engage more people in political issues. People given the opportunity to vote directly on issues will — at least according to optimistic theory — get better informed before making their decision.

So, why are referendums in Manitoba even more rare than the Winnipeg Blue Bombers winning the Grey Cup, which last happened in 1990?

Manitobans with good memories might recall the 1983 opportunity to vote on global nuclear disarmament and English-only language laws; those with even greater powers of recall might think back to a 1968 vote regarding whether billiard halls could open on Sundays.

But almost all civic and provincial issues since then have been decided by elected politicians. And that’s as it should be.

What Winnipeg and Manitoba don’t need is the ballot-box chaos experienced in some other jurisdictions. In Switzerland, citizens answered 103 referendum questions during 31 votes over a 10-year period. Among the examples of the mischievous issues referendums can raise are a 2012 Arizona ballot initiative pondering whether the state should claim sole ownership of the Grand Canyon and a 2012 Colorado proposal for a state commission to track outer-space aliens (both were defeated).

Referendums, especially the type that are binding on politicians, can be problematic. People deciding a complicated matter should have a thorough understanding of the issue and its ramifications; referendum questions tend, however, to be decided by emotion-driven responses that favour the status quo. That reality can create opportunities for political mischief-makers to manipulate the outcomes.

Referendums, especially the type that are binding on politicians, can be problematic. People deciding a complicated matter should have a thorough understanding of the issue and its ramifications; referendum questions tend, however, to be decided by emotion-driven responses that favour the status quo. That reality can create opportunities for political mischief-makers to manipulate the outcomes.

It’s possible local projects that are now admired for their long-term vision, such as construction of the Red River Floodway and the transformation of The Forks from an ugly rail yard into an internationally renowned gathering place, would have been voted down if left to the will of citizens at the time.

Rather than the so-called direct democracy of referendums, Winnipeg and Manitoba are better served by the current system of representative democracy. Duly elected politicians study an issue, notify the public of their intended action, allow time for debate and then act.

Call it indirect democracy. The theory is that we vote for smart, ethical politicians whose campaign promises match our priorities and aspirations. Then we let them do their jobs; if they don’t do them well, we fire them at the next election.

We can discuss at length whether Mayor Brian Bowman has abandoned his campaign promise to reopen the intersection, choosing instead to support the referendum and say he will consider the results to be binding. The reality of the political moment is that Mr. Bowman had no other choice.

Like it or not, Winnipeg is heading to a referendum, and citizens should inform themselves before entering the voting booth. To what degree would a reopened intersection help revitalize downtown Winnipeg, making it more appealing to shoppers, tourists and downtown dwellers? What effect would reopening have on rush-hour traffic, including the many buses that use the intersection? What will be the complete financial cost?

We expect our elected leaders to be well informed before they vote on important issues. On Oct. 24, this one’s on us.