Truth, lies and no escape

Laws preventing victims from accessing information about their own lives serve as perverse obstructions of 'justice,' leaving hope of recovery cruelly out of reach

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 25/09/2020 (1902 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Four years ago, the journalist Erika Hayasaki wrote a story in Wired magazine about the unusual case of a woman named Susie McKinnon, who was born without the ability to retain autobiographical memory — which is to say, she cannot remember events from her life as an episode, as if watching snippets from an old film.

In every other regard, her mind functions in a perfectly typical manner. She is happy. She has a great career, a loving husband, good friends, a bright sense of humour. She knows facts about her life, such as when she and her husband went on vacations; she just retains no memories of those trips. And she cannot dream of the future.

Essentially, Hayasaki wrote, McKinnon’s mind frees her to live in the moment, untroubled by past events and largely unconcerned about what comes next. The writer contrasted that with a media sensation over an individual who has exceptional autobiographical memory, born from a compulsion to record events following childhood trauma.

“When it comes to people with highly unusual memories, it’s not clear that we as a culture are so good at choosing who to envy,” Hayasaki wrote.

Over the last month, I have been thinking a lot about memory. The way it is both ephemeral, and yet can be more powerful than almost any other force in the world. The way it does not define who we are, as McKinnon’s example shows, but how we still hold onto our memories as if, without them, we’d be adrift in the storm.

“When it comes to people with highly unusual memories, it’s not clear that we as a culture are so good at choosing who to envy.”–Erika Hayasaki

To the majority of us who can remember in this way, this attachment makes sense. Memories can be precious even when painful. When someone you love walks out the door, your bond to them lives as a memory until you see them again; when you remember something that hurt, you also have a chance to see how far you’ve come.

Still, memory is not static. It is not like a Polaroid, printed and unchanging; it is living and ongoing. It is pliable and can be shaped by new information. It is also not just one set of processes: there are many types of memory, each serving different functions. Only some of them look like a film, and only some of those film clips are saved.

It’s how you can forget the name of a childhood teacher, but remember the electric feel of one person’s touch on your skin. How you can forget what you did after work two days ago, but remember a random conversation years after the fact. How some details are discarded while others remain: some for reasons you can see, and others you can’t.

So what do you do when flashes of memory are the only evidence you have of a crime that happened to you?

Former cop helps Winnipeg woman fill in the blanks of her tortured childhood and youth

Posted:

Nearly four decades after he helped send a battered four-year-old girl's abusive father to jail, a former cop helps a Winnipeg woman fill in the blanks of her tortured childhood

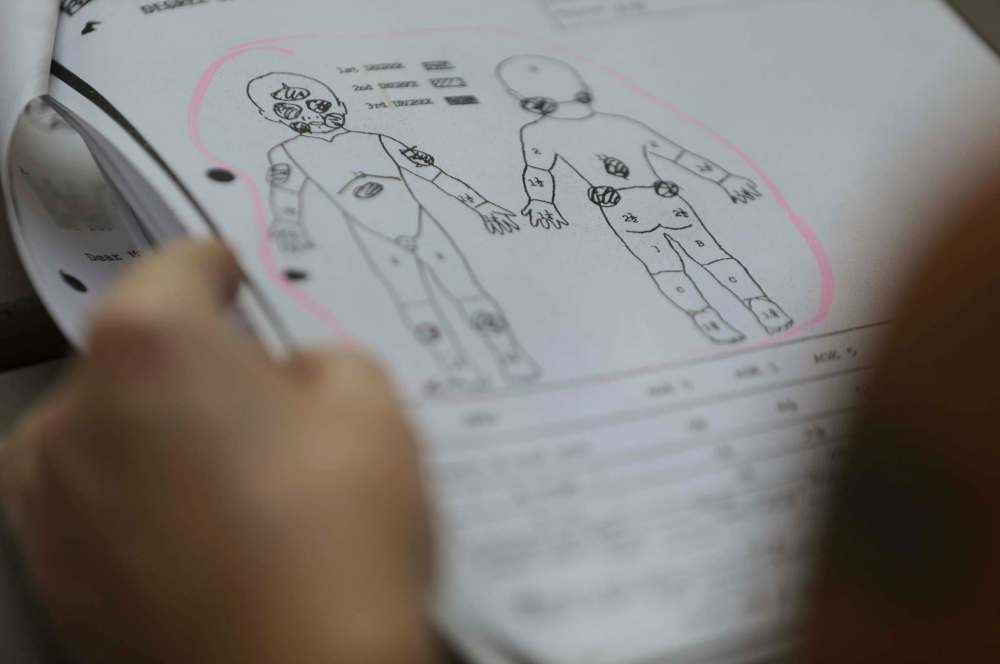

That is the theme of my feature story in this week’s 49.8 section. It is a story I am grateful to bring to light. For the last two months, I’ve gotten to know Payton, whose 25-year journey to uncover the truth of her own childhood abuse led her through systemic barriers, and to make a remarkable — and improbable — reunion.

From the start, her story captured me. Over the years, I’ve read many things about how victims move through the justice and child-welfare systems. I’ve read many things about the supports that are lacking, the oversight that can fail, the gaps kids can fall through. But I’ve never read about a journey that centred on this question.

What right do victims have to information about them?

This is a compelling question, one that sits at the intersection of memory, trauma and healing. It is one about how victims find what they need to know their own story. It is fundamentally a question of who information collected by public institutions belongs to; is it right if those institutions know more about your trauma than you do?

Because if memory is powerful, it can also be confusing, especially when it conflicts with the stories others have told you. It strikes me that Payton’s experience of having her abuse dismissed or concealed by family members will not be uncommon; there are likely many survivors who see, in her journey, echoes of their own stories.

If memory is powerful, it can also be confusing, especially when it conflicts with the stories others have told you.

In her case, the strength of her memory served as a double-edged knife. With it, she struggled to reconcile the pain to which an abuser subjected her, and the confusion of being told it didn’t happen. Without it, she would never have found the truth, and that sense of validation is often a critical part of healing for survivors of abuse.

So what processes are in place to ensure that victims have all the facts that are out there to give them that validation? How can they be improved? How often do we ask ourselves critical questions about how institutions are set up to support survivors, not just in the initial days after their traumas, but years down the road?

While I worked on telling Payton’s story, I found myself wishing for her a mind like McKinnon’s, free from the images of pain that the mind saves and relives, like film clips jumbled out of order. But more than that, I wished for her a life where it did not require so much tenacity to ask for, and receive, facts about what those memories meant.

As part of my research for Payton’s story, I spoke with Dr. Jim Hopper, a Boston-based clinical psychologist and independent consultant who specializes in the impacts of abuse. Hopper was struck by the details of this case, including the barriers that Payton had faced in trying to access records of what happened to her.

“At the heart of trauma and seeking justice must be the empowerment and connection to the survivor,” Hopper told me. With that in mind, laws restricting their access to information about their cases, he said, would be “profoundly disempowering and re-traumatizing to people who are trying to heal and understand their own lives.

“It’s the opposite of what you’d want for someone who is trying to heal from trauma.”

There needs to be a way to secure the truth, for those searching. If memory is all some have, it won’t be enough.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.