Tethered by trauma, driven by truth Nearly four decades after he helped send a battered four-year-old girl's abusive father to jail, a former cop helps a Winnipeg woman fill in the blanks of her tortured childhood

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 25/09/2020 (1903 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

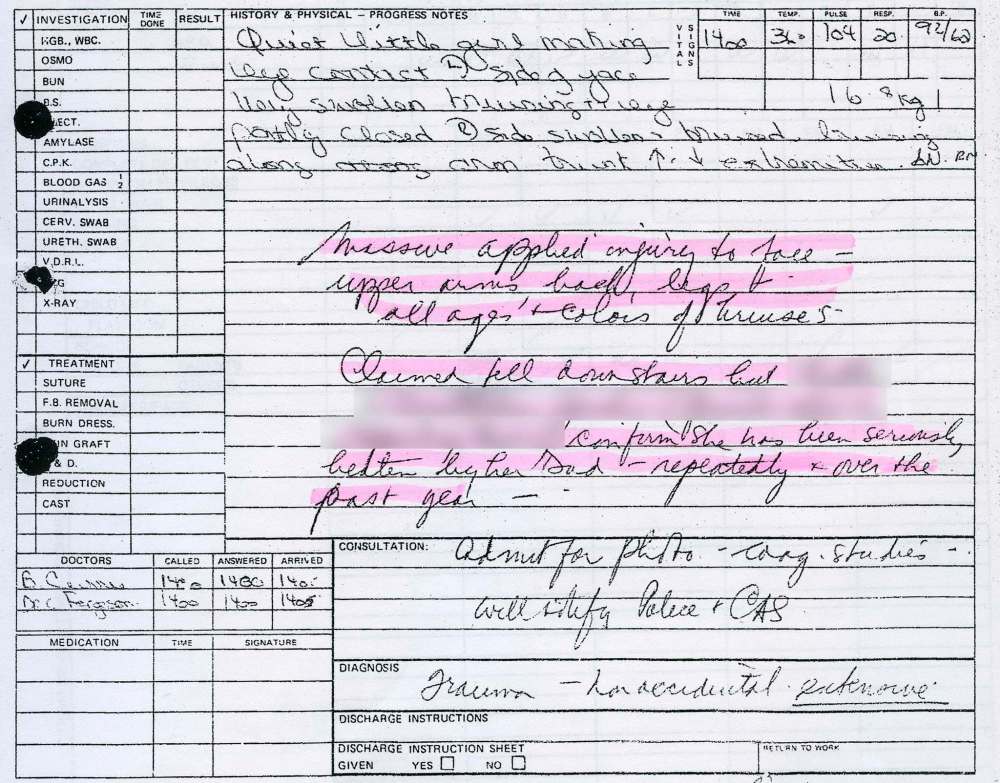

On one late summer day in 1981, a woman takes a little girl to the Children’s Hospital. She is four years old, tiny for her age, and both her eyes are ringed by swollen black and purple bruises. The woman, who is not the girl’s mother, tells a doctor that the child’s father had beaten her with a belt and his hands.

Nobody knows it yet, but years from now, the things put into motion this day will weave a new story, one that no one would have expected. Notes that are taken will come back to light; lives that intersect will be reconnected. Someone searching for the truth will find what was hidden.

More than that, she’ll find a reason to live.

For now, the hospital’s child-abuse team leaps into action. The doctor in charge is named Charles Ferguson. He is the director of ambulatory care, and widely known as a lion for abused children; in 1973, he’d co-published the first paper on child abuse in Canada. When he dies in 2014, he will be remembered as a hero for Manitoba’s kids.

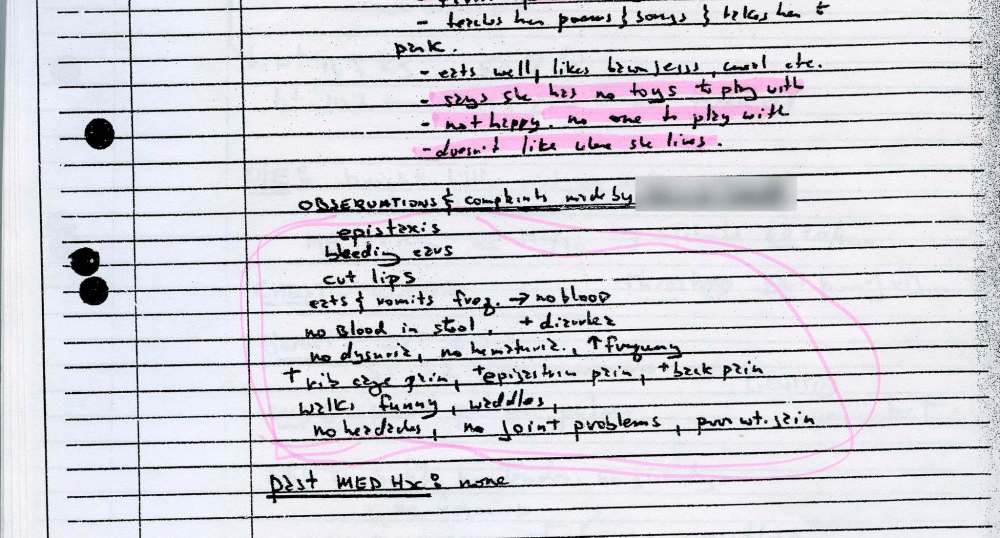

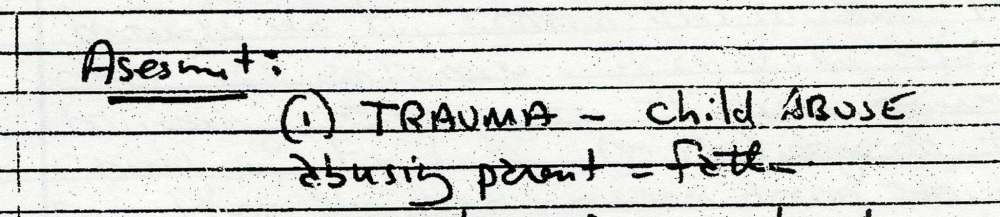

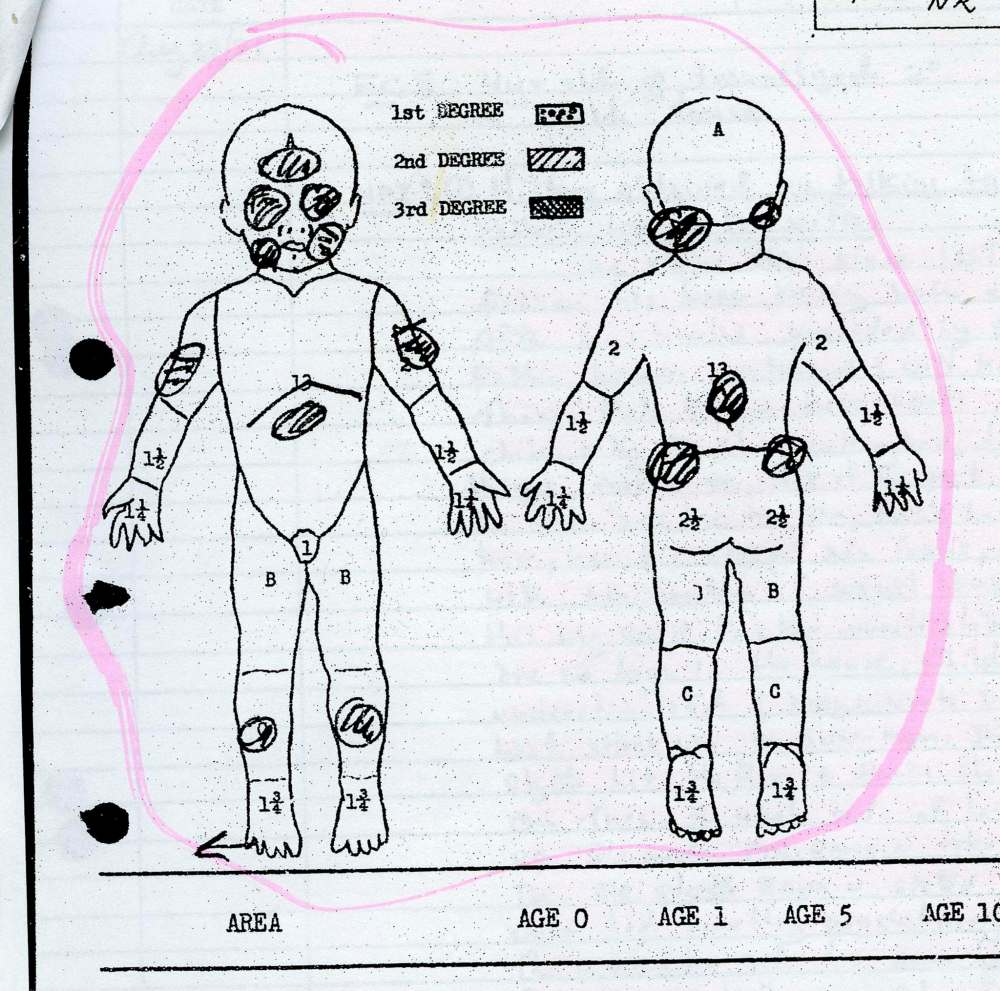

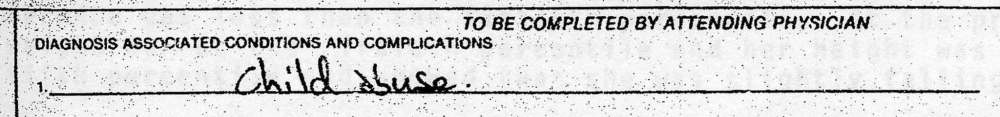

In his notes, he makes a grim tally of the girl’s injuries. There are the bruises on her face and an angry red lesion on the back of her neck. A fresh bruise on her thigh in the shape of a shoe sole; an older bruise on her arm in the shape of a hand. The corners of her eyes are red where blood vessels burst from the force of blows to her head.

At first, the little girl tells the doctor that she fell down the stairs.

Ferguson calls the child’s family doctor, who had seen the girl twice that week with her father. The girl is “disturbed,” says the doctor, who apparently accepted her father’s explanation that her wounds were self-inflicted. In a letter to a social worker, Ferguson drily notes that the doctor had a duty to report “such severe injuries” to authorities.

Many things happen that day at the hospital, and the next. And the one after that. The little girl doesn’t really understand. She doesn’t know why she’s there, or why doctors and social workers hover around her with solemn faces. She does not know a life where little girls are not beaten, and so doesn’t think anything is amiss.

Two police officers come to talk with her. Her young eyes drink them in. One of them is lanky, with a quirky, genial face; the other wears sunglasses and a certain swagger. “A typical cool cop look” is how she will describe that one, much later.

Soon, another police officer comes to take photos of her injuries. When he photographs her from the front, the little girl glares at the camera, electric blue eyes defiant, lips pressed into a sullen line. But in photos taken from the side, her battered body slumps and her chin hangs limp to her chest.

The two police officers leave the hospital and go to the house in south Winnipeg where the girl lives. What they find leaves them unsettled. Most of the house is nicely furnished, but the child’s bedroom is barren except for a mattress on the floor. There are no toys in the house. Little food. A lock on the outside of the child’s door.

That evening, they take her father to the Public Safety Building for questioning. At first he’s obstinate, almost smug. He tells the officers that his daughter is clumsy, but none of his explanations for her injuries add up.

Hours later, his tone changes and he confesses to some of the abuse a witness had reported. Some, but not all.

He will be charged with assault. Eventually, he will plead guilty and receive a nine-month sentence.

The next day, the officers come back to the hospital to visit the girl. The lanky one hands her a big brown teddy bear. She clutches it eagerly and feels a swell of joy.

It’s the first toy she remembers having, and though the bear itself will be lost somewhere to the passage of time, she will never forget the feeling of cuddling it to her chest.

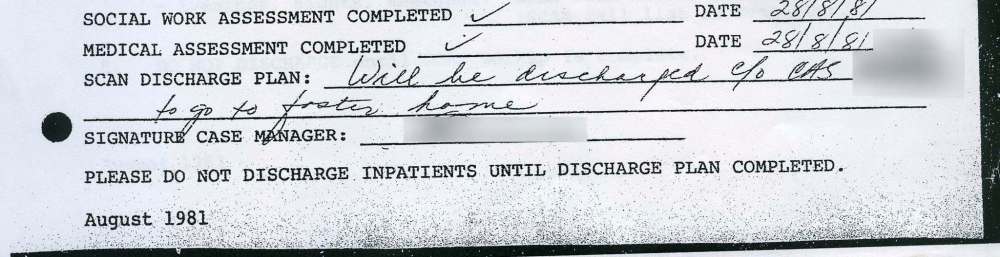

A few days later, before the little girl is discharged from hospital and placed in foster care, Ferguson types up a letter to the Children’s Aid Society, the precursor to today’s Child and Family Services. There’s “no question” the girl needs protection, he writes: “My view would be that the perpetrator of these injuries is a seriously disturbed individual.”

Soon, the police officers finish their paperwork and their minds shift to their next case, the way they’ve been trained. There’s a sense of satisfaction in the resolution to this one. An abuser has been charged, and the victim is in the care of social workers. The system has worked; a child has been protected.

● ● ●

Every morning when Payton wakes up, the memories start playing in her head, like a film that runs on a loop with no end. It has been this way as long as she can remember. There are about 100 core memories, she thinks, a flickering record of her childhood and early teen years cycling in and out of her mind’s eye.

She remembers the one filthy shirt she had, with a smiling moose on the front. Being hungry. Being trapped in a bare bedroom, alone. The sound of broken glass, of screaming, of fists hitting skin. She remembers her father coaxing her to crawl up the stairs to the bedrooms and then, with a shove of his foot, kicking her back down.

Then there are the memories that came after the hospital. Not very long after. The ones when her father came back into her life and began taking her for weekend visits. The abuse changed then; he didn’t hit her again, but he found other ways to hurt and control her. She does not want to remember those things. But she cannot forget.

And she remembers the day she left foster care and went to live with her paternal grandparents. They were the ones who allowed her father to visit, and she remembers their anger, too. Her grandfather “only” hit her about seven times, she says, but her grandmother smacked her more often.

When her grandmother died, many years later, Payton called her best friend to celebrate the news.

Every now and then, a good memory slips into the loop. There aren’t many. But she remembers the police officers who visited her in hospital, and the teddy bear they gave her. It was the first time she can remember anyone being kind to her, and when she pauses on that image she still feels a warm flush of joy in her chest.

“That toy was everything, I think, and that’s why it’s embedded in there with all those horrible memories,” she says.

At 43, Payton — which is not her real name — still looks like the child that stared at a police officer’s camera back in 1981. She has strawberry blond hair and a confetti of freckles that dust her skin. She has those electric blue eyes, framed by eyelids that flutter when she’s about to emphasize her next phrase.

When Payton was still in her teens, she searched for ways to keep the memories at bay. There was a lot of booze, a lot of drugs, a lot of men. There were a lot of days and nights spent reeling around Winnipeg’s dark corners, trying to silence the litany of angry voices and images that howled through her head.

“I was on a death mission,” she says. “I didn’t care about anything…. If I went to bed each night and woke up the next morning, it was a bloody miracle, because I shouldn’t have.”

One night, when Payton was 19, she told her friend Wade about the things she remembered. He was driving her home from a Garden City bar and he’d asked about her family life. As she spoke, her thoughts began to spill out, whirling from one image of trauma to the next. It was the first time she’d told anyone.

Over the years, the two fell out of touch. But Wade — who asked not to be identified to help protect Payton’s privacy — never forgot the shock he felt when he heard her story.

“It was just disbelief,” Wade recalls. “I remember sitting there quietly, listening, because it all started to come out. All I could do was just sit there and take it in…. She sort of comes off like she’s got it under control. The first thing she’ll say is ‘I’m OK, it’s fine.’ Looking back now, I didn’t realize that was her defence mechanism.”

“I have a history of lies, I have a history of stories, I have different versions of what happened.”–Payton

At 27, Payton got sober, retreating to her apartment to detox on her own. She cut ties with many of her friends and sought therapy, for which she found few resources. And she began trying to piece together the events of her life in earnest, trying to make sense of the jumbled images that played every day in her mind.

It was hard to know if they were real. Nobody had ever told her. When Payton was still a child, she tried asking her grandparents what had happened. She knew her father had gone to jail and that’s why she no longer lived with him, even though he still came to see her and spent time with her alone.

“He slapped you a few times,” was all her grandmother said. Her grandfather’s explanation was that her father got angry at her once, and other people got too involved. When she asked her father — or “Asshole,” as she calls him — about the images that haunted her, he was evasive, even coy.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” he sometimes replied.

When Payton was seven, she learned to pick the locks on her grandparents’ filing cabinet, where she rifled through court documents she was too young to understand. On her 18th birthday she went to the Law Courts and asked for records relating to her father or grandparents. The clerk told her she could not see them, and did not say why.

Still, the memories raged in her head, vivid and unending. She had so many questions. Sometimes, she wondered if the things she remembered were real or the product of a broken mind. She told herself they had to be there for some reason, and that somewhere, there must a truth out there to find.

“I have a history of lies, I have a history of stories, I have different versions of what happened,” she says. “I’m full of all these tales of what happened and my memory is a mess, and I’m trying to fix my head. So I was driven to prove them wrong. No, that’s not it. To prove me right. I had to prove me right.”

For years, her attempts to track down proof of what happened in her life turned up little. But in the summer of 2009, an idea sparked in her mind: she had those clear memories of her time at the Children’s Hospital and of the police officers who talked to her. She contacted the hospital, asking if they still had her record on file.

The reply came back: yes, they did. She could have a copy, unredacted.

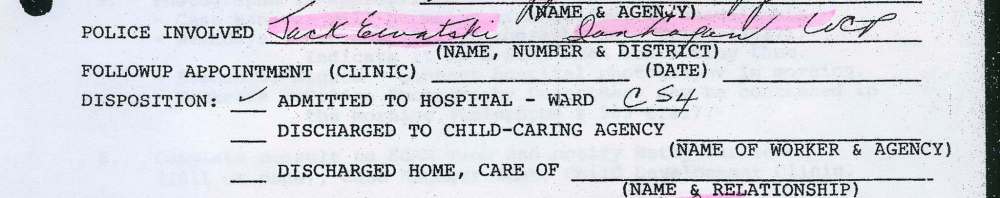

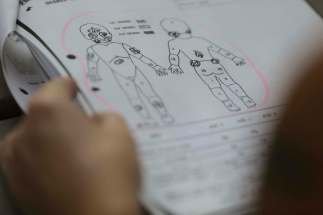

When she got the file home, she flipped through its pages, almost in shock. There, in her hands, was a complete record of the initial response to her abuse. Diagrams of her injuries. Notes from doctors and social workers describing what Payton and a witness had told them about the psychological and physical torment she’d suffered.

For the first time in her life, Payton had proof her abuse had happened, in the ways she’d remembered.

“It’s a high, and it’s an elation, and it’s a ‘f–k you all. I was right, you were wrong,’” she says. “I knew it was real.”

But the paperwork also left her with more questions. If she had been so badly abused, then why was her father allowed back into her life? Why had she been placed in the custody of his parents? Had she been given any support to heal? Had anyone —anyone at all — tried to follow up on what became of this battered little girl?

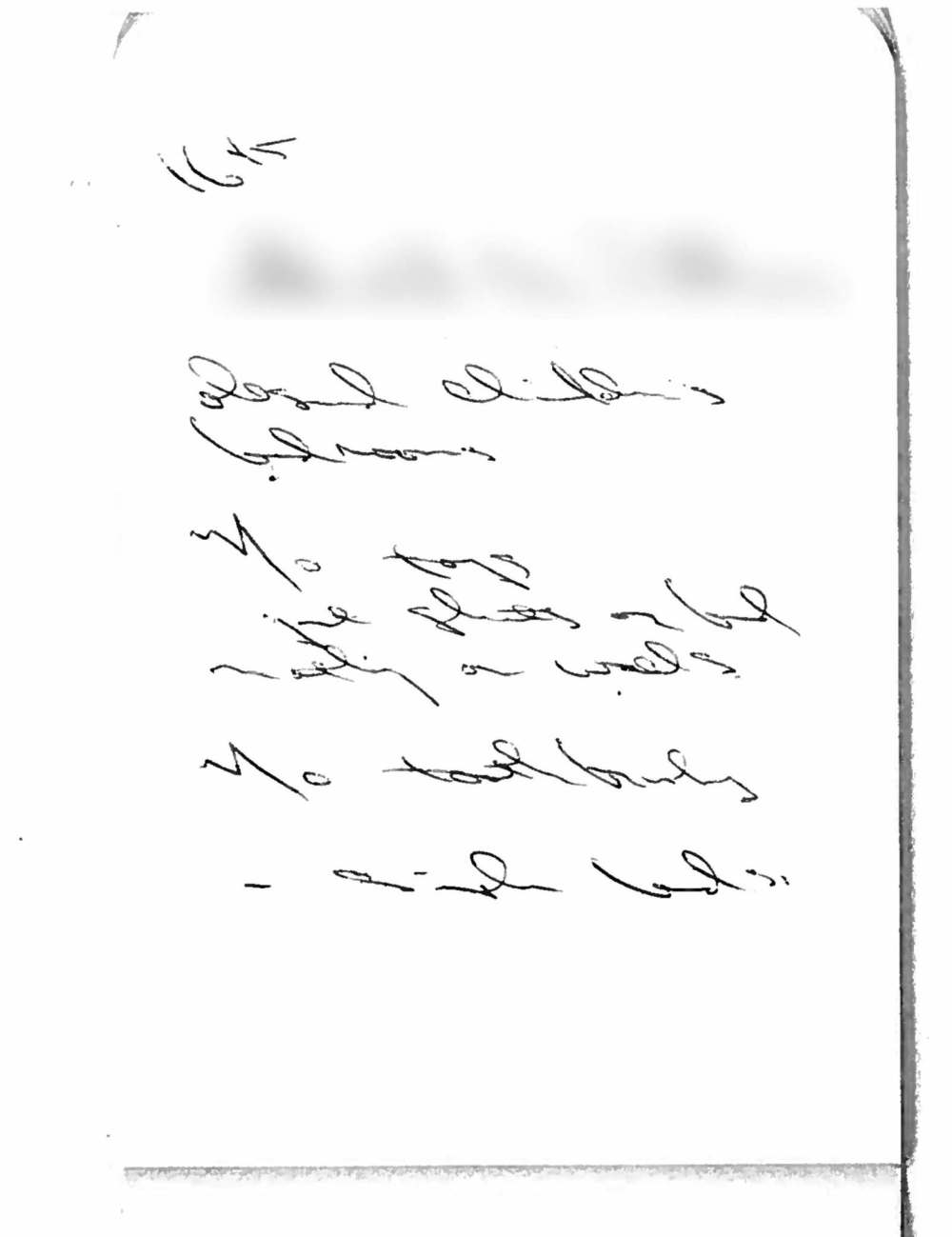

Something in the notes gave her pause. On one page, someone had written the names of the two police officers who visited her in hospital. The handwriting made one name illegible, but the other was clear. It was a familiar name, she thought, and when she typed it into Google and saw a flood of news stories come up, she realized why.

Maybe he would have more answers, she thought. But she could find no way to contact him, and so let it slide.

Soon, the paper trail ran cold again. She was finally able to access therapy, which helped, and eventually located court documents revealing how her grandparents had kept Payton’s mother out of her life. She stuck the envelope containing the hospital records onto a shelf in her closet; after a while, she forgot it was there.

But in April, with life sidelined by the COVID-19 pandemic, Payton was preparing to shred some old papers when she came across the envelope again. She read the file all the way through, and when she got to the one legible police officer’s name, she decided to take another shot at tracking him down.

This time, when she searched his name, an email address popped up on the screen. In that moment, Payton knew she would contact him, though it took her more than two hours to decide what to say. Finally, she sat down and wrote out her message, topping it with a deliberately vague subject line: “General Inquiry.”

“Hi Jack,” she began. “I was wondering if I could pick your brain with some questions that I have about something that happened in 1981. I know that was a long time ago but I am hoping that you may have some answers for me.”

After explaining more about her situation, she clicked “send.” For the next two days she waited anxiously, curious if he remembered her. Hoping he would answer, trying not to expect it. Not sure exactly what she would say if he did.

●●●

It was raining that afternoon in mid-May, as Jack Ewatski parked at The Forks and walked across its empty plaza, towards the river. He didn’t come into Winnipeg too often anymore, not since he and his partner had built a home outside the city and he’d settled into a civilian job at Assiniboine Community College in Brandon.

At 68, Ewatski had memories too, curated from the highlights of a 34-year career with the Winnipeg Police Service, one that saw him rise through the ranks until he was, for nine years, the city’s chief of police. After retiring in 2007, he’d served a two-year stint as deputy police commissioner in Trinidad, returning to Manitoba in 2012.

He could remember the first arrest he made. The first fatal car accident he attended, and the limp feel of the body he helped lift out of the vehicle. He remembered his part in investigating the 1984 murder of Candace Derksen and how it felt 22 years later when, as chief, Winnipeg police made an arrest in her killing.

And he remembered that case in August 1981 when he and his partner, Ian Logan, got a call about a suspected child-abuse victim at Children’s Hospital. Ewatski was 29 years old then, eight years into his career with WPS, but that type of case was still relatively new to him, part of a twist in his career path he hadn’t expected.

At the time, Ewatski recalls, child-abuse investigation was still in its infancy. The dominant mindset throughout the justice system was that the law had no place intervening in how parents discipline their children. What happened inside a home was widely seen as a private matter, and authorities hesitated to pry too deep.

But things were changing. In early 1981, Ewatski and Logan were working in what was then called the juvenile unit, mostly handling cases involving youth offenders, when an inspector called them into his office. He handed the pair a few files of suspected child-abuse cases he wanted them to handle.

“He said, ‘Don’t worry, when you finish these, you’ll go back to the regular work that you’re doing,’” Ewatski recalls. “I don’t think anybody at the time appreciated the scope and size (of the child abuse) that was out there.”

None of them knew it yet, but that meeting would mark the unofficial start of the WPS child-abuse unit.

Logan was a natural in the role; he was empathetic and caring. He carried photos of his two young daughters in his wallet, to show little victims that he had kids just like them. He would go on to lead the child-abuse unit, and after he died in 1987, the provincial child-abuse advisory launched an award in his name.

But in August 1981, the pair were still feeling their way through how to investigate these cases. They met with the little girl, who Ewatski found to be quiet and reluctant to speak. They were disturbed by what a witness told them about the abuse the child had suffered, as well as the scene they found in the family’s house.

“I recall mattresses on the floor, a blanket or two,” Ewatski says. “But nothing else was in the room. No toys. No colouring books. Nothing that would indicate that a young child would be in the room… nothing to indicate a child lived in the house at all. That was a memory that stuck with me. It was very profound.”

The next day, Logan arrived at work with a teddy bear to give to the victim. That’s how he was, Ewatski says with a smile; he didn’t know this at the time, but the toy originally belonged to Logan’s nine-year-old daughter. He’d asked if she would be willing to share one of her toys with a child he was helping, to which she gladly agreed.

Sometimes, in the years that followed, Ewatski wondered how that little girl’s life had turned out.

“I really believed that things worked out for the best,” he says. “I just firmly believed that a decision was made in the best interests of the children, believing that the systems put in place would continue to support and protect them. So then you move on, and hope for the best.”

“I just firmly believed that a decision was made in the best interests of the children, believing that the systems put in place would continue to support and protect them. So then you move on, and hope for the best.”–Jack Ewatski

Ewatski’s career moved on, but that case never left him. Over the years, he spoke about it more often than any other case he’d worked on. He’d told the story to recruits at the police academy; as chief, he told it at a national conference of Canadian chiefs of police; when he was in Trinidad, he used it as a teaching example.

In fact, he’d spoken about the case just two months earlier as part of a training program for First Nations safety officers he was running at Assiniboine Community College. He’d handled other cases that had been more physically horrific, he’d explain, but the psychological abuse in this one stuck with him.

“Why do I continue to use this story? I don’t know. It was meaningful to me, and I was hoping that people would get the message that you’re going to see and do a lot of things,” Ewatski says. “And some things are going to stick with you, and you’re going to have to manage and navigate that through your life.”

So when the email from Payton had landed in his inbox just a couple of weeks earlier, Ewatski was taken aback. It was almost as if she knew he’d been talking about her, he thought, though that obviously wasn’t true. Never before had a victim of a case he’d worked on reached out; he was curious, but guarded.

“The first question that came to mind is ‘why?’” he says, and then laughs. “That’s maybe the cop coming out.”

Now, as he walked across The Forks plaza, still empty in the early weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic, Ewatski was nervous. He hadn’t asked what Payton looked like or what she’d be wearing. He didn’t need to. As soon as he saw her, standing by the river, he knew: it was the child he’d met, long ago. The same face. The same eyes.

For a few moments, the two looked at each other. Ewatski asked if they needed to keep up social distancing.

“I’d be disappointed if we did,” Payton replied.

As they embraced, Ewatski felt tears well up in his eyes.

At a nearby restaurant, the two fell into conversation for hours. Payton had a list of questions about the investigation of her abuse and the evidence they’d found in her case. Ewatski told her everything he could remember. She asked about his life, and where it had taken him; it was as if those details made her memories more real.

“He knew me at my most vulnerable time and I didn’t even know him at all,” she says. “I asked him how old he was, how long he’d been a cop, because I wanted to know. It was like I’d known him for my whole life because he’d been in my head. But at the same time, I knew absolutely nothing about him.”

He had questions for her, too. The last time he’d seen her, she’d been at the hospital, about to be taken to what he hoped would be a happy new home; he’d later testified at a guardianship hearing to determine whether she should stay in foster care. At first, Ewatski was excited to find out what had happened to her from there.

She told him about how she’d been turned over to the custody of her grandparents, who allowed her father back into her life. About how the abuse had continued, in many ways. How she’d fought to survive the flurry of memories that wheeled in her mind, and how she was now fighting to uncover the whole truth of her life.

“It didn’t take long for that sense of elation and joy at being able to connect to just drop right off the table,” Ewatski says. “As she shared much more of her life with me, yeah, I felt deeply, deeply saddened for a number of reasons. And almost to a point where anger kicked in, as well. And a feeling of responsibility.”

So he kept trying to fill in all the gaps for her, because that’s all he could do. There were some incidents of abuse a witness had told him about that Payton didn’t remember. He told those stories to her cautiously at first, worried that they would be too painful for her to hear, but she savoured each new piece of information.

“There were a couple of points in particular, I could just see her be like ‘wow,’” Ewatski says. “Between the two of us, we were able to put this picture together… she’s here, she’s alive, she’s resilient, she’s brave enough to reach out now and say, ‘I may need some details from you that maybe might hurt me even more, but I need this.’”

Once, two people’s lives intersected at Children’s Hospital. Thirty-nine years later, the thread that tied them that day pulled them back together, in ways that would lead them both to see things in a different light. Ewatski was not the first person who believed Payton about her abuse; but he was the first who shared her reality.

“I finally had somebody, an ally, a person, that was real, that believed me,” she says. “And not because of what I was telling him, but because he was there and he knew first-hand what had happened. He knew already, and I didn’t have to get validated, or have to explain anything.”

After they parted that day, the two kept in touch, texting often and visiting whenever Ewatski was in Winnipeg. In his mind, he turned over what had happened to her, after the police and the courts had gone away. He wondered if they could have done something differently to save Payton from the abuse that continued through her teens.

“If I would have known… we would have intervened,” he says. “I would have intervened in some way.”

At the time, that wasn’t his role. It doesn’t appear to have been anyone’s. For that, he notes, Payton suffered.

“I’m glad we did what we did and how we did it,” Ewatski says. “But I feel a level of responsibility in terms of how things played out at the end. We talk about the system maybe failing her. I was part of a system. Yeah, it was no longer a police matter, so to speak. But I’m part of the system that let her down.”

“I’m part of the system that let her down.”–Jack Ewatski

●●●

As summer bloomed over Manitoba, the story of Payton’s life came together in pieces. With Ewatski’s advice and encouragement, she filed six freedom of information requests with four agencies, seeking documents of her case held in official files. Two came back, including a redacted copy of Ewatski’s 1981 police notes from the case.

She filed a request with the court to unseal records of her 1982 guardianship hearing, at which Ewatski and social workers involved in her care testified. She was told a judge would have to rule on whether it could be released. The wait was agonizing; these barriers make her feel powerless, as if she’s being victimized again.

“That’s what Jack calls it, too,” she says. “Revictimization. It’s my history. I need to know, I want to know and I have a right to know what happened to me, without all the different stories causing my head to spin every day, not knowing what reality is. It’s not fair to me. And everybody else is doing it to me, by not letting me have it.”

Payton kept pressing. CFS would not give her access to her file, but they did agree to let her ask questions about it for a social worker to answer. She came up with an initial list of 28 questions, designed to ferret out details about the decisions made in her care with an exacting, almost lawyerly precision.

What she found ultimately painted a picture of a series of systemic failures, starting with the family doctor who saw her injuries and declared them self-inflicted, through to the child-welfare agency that — despite the objections of two social workers — turned Payton over to her grandparents and promptly closed the file, preventing further monitoring.

One social worker involved in Payton’s case warned that her grandparents were “very protective of their son” and might not protect Payton from her father. Another worried the grandparents would not be able to “adequately deal with the emotional abuse and trauma” that Payton had suffered, according to notes on her file.

Yet for the seven months Payton was in foster care, her father was allowed to visit her monthly, even as he faced charges for her abuse. She didn’t remember those visits. After her grandparents won custody, a protection order preventing him from seeing her was dropped, and there was no followup on how she was doing.

As the details came together, Payton felt something inside of her changing.

“It helped put pieces where they needed to go,” she says. “When it’s all jumbled up in your head and you’re trying to understand if it happened or if it didn’t happen, and then you find out it did, it’s relief. It takes the pressure off of trying to understand whether you’re living in reality or not… it’s like, ‘OK, it did happen; it was real.’”

"When it’s all jumbled up in your head and you’re trying to understand if it happened or if it didn’t happen, and then you find out it did, it’s relief."-Payton

It’s uncommon, experts say, for children to retain such a volume of clear memories from before age five as Payton did. For her, that is both blessing and curse. The memories haunt her, but without their clarity, she may never have known where to start pulling the threads that would lead her to the truth.

That’s something Christy Dzikowicz has thought about, since meeting Payton recently. As executive director of Snowflake Place, a non-profit that provides support to victims of child abuse, Dzikowicz knows how the system can become a maze, loaded with barriers for survivors seeking support and information.

“She’s an extraordinarily intelligent person,” Dzikowicz says. “The fact she survived it and got to a place where she’s piecing together her story, which is an exhausting task, it does paint a picture of what that might be like for anybody who doesn’t have the same skill set, or the same memories.”

Above all, Dzikowicz says, her story highlights a rarely-asked question: what right do victims have to information about them? How does that impact victims who are too young to participate in a justice process and who may not have anyone in their lives who can — or will — tell them the truth?

“Imagine how much different it would be if she didn’t have these memories,” Dzikowicz says. “At a minimum, she starts from a place of understanding what she’s been through. When you go to a therapist, what do they do? They ask you to describe your life, your history. If you can’t tell that story, it makes it really challenging.”

There is one more thing Payton found. Although most police records of the criminal case against her father appear to have been lost or purged, the WPS did find nine photos taken of her in the hospital on that day in 1981. In May, they arrived in Payton’s mailbox on a disc. She called Ewatski to support her while looking through them.

When she shows the photos to friends, she is matter-of-fact, pointing out where the bruises show the splay of her abuser’s fingers. It is hard for them to look. Wade is haunted by the images, by the difference between the defiant way the child looked at the camera, and the way she slumped when photographed from the side.

“It strikes me that’s the moment that the camera caught her breaking,” he says, and blinks back tears.

To Payton, it’s not the posture or the bruises that most knot up her guts.

“The eyes broke me,” she says. “It’s the anger and the hatred in the eyes, because they’re my eyes. When I’m doing my makeup, they’re still my eyes. That devastated me, because it hasn’t changed. And that little girl in those pictures, that’s all she felt. And I know that’s all she felt, because it was me.”

She sighs.

“I was broken and destroyed already at that age. That tore me apart inside. I felt like there was no coming back from that. And that little girl didn’t deserve it.”

●●●

On a crisp afternoon in early September, Payton slides into the banquette of a Polo Park restaurant. While she waits for Wade to get off work, she sips a Corona and chats about what she hopes will come from telling her story. Soon, an email notification pops up on her phone; her eyes light up as she begins reading it out loud.

“Your inquiry has been reviewed, and unfortunately…”

She trails off as her face falls, and slides the phone across the table. “Here, you can just read that.”

The email is from her contact at the Law Courts. A judge has ruled that, by the provisions of the Child Welfare Act, the court does not have the power to unseal her guardianship hearing record. She could find a lawyer to challenge the ruling, but she is running out of options.

Payton taps on her phone, forwarding the email to Ewatski, and sinks into the banquette.

“That just crushed me,” she says. “I’m pissed off. A dead-end again…. It’s my history. It’s my story. I should have all the rights to it. Not everybody else, just me.”

"It’s my history. It’s my story. I should have all the rights to it. Not everybody else, just me."-Payton

She is nearing the end of the paper trail now, the journey she has followed since she was 18 years old. There are some questions that may forever remain unanswered. She may never know when or for how long her abuser was incarcerated; family photos offer no hint of a gap when he might have been in jail.

But at least she has a timeline of her life. She knows most of the truth about what happened to her, and why. It took her more than 25 years to construct that picture, in pieces tied together by a stubborn tenacity and a little bit of luck.

Truths once confined to the archives of public agencies, dredged up by the force of two people’s memories.

Yet maybe the greatest value of the search has come, not from the documentation, but from the connections it knit together. Payton has a team of people around her now. There is Dzikowicz, with whom she talks about ways to get involved in supporting abused children. There is Ewatski, who is always there to offer guidance.

“Everybody always says when they see us together, he’s very protective of me,” she says, with a sad smile. “And I don’t see that. I don’t see that side of it. Probably because I’ve never had anybody be protective of me, so I don’t know what that looks like. Which is very hard to say.”

And there is Wade, who she reconnected with earlier this summer while preparing to tell her story. He’d often thought about her over the years, though he could find no way to reach her. Now, they meet every week; while Payton sits for a Free Press photographer, Wade watches, warily asking how the paper will ensure her anonymity is protected.

“Her army,” Wade says, with a wry smile. “She coined that one. I’m proud to be in her army.”

All these bonds forged around Payton’s journey have changed her army, too, in ways they’re still coming to see.

“I believe things happen for a reason,” Ewatski says. “We’re trying to still figure this all out. It’s still somewhat a little baffling for me at times: why did this happen? But I view this reconnection as it happened for a good reason. And I’m really glad it did.”

What he does know is that whenever he taught Payton’s case to police recruits, part of the lesson was you should always try to go into a case with empathy, because the words you choose could go a long way. Now, knowing how deep her memories run, he finds himself wondering about other cases, other victims, other stories.

“Where are they now? I’m curious,” he says. “It leaves me with a sense of, I wish that I knew what I know now back then, in terms of how to be a police officer that has the ability to handle situations differently than was the norm back then. It’s a feeling of regret. We all have things we wish we could do over again.”

As for Payton, in the months since she met Ewatski, her personal journey has become a mission. She has written out a list of things she wants to see change, starting with a belief that all victims should have access to their files without having to wade through freedom of information requests, the courts or intermediaries at CFS and other agencies.

“I’m in awe of her strength and I’m extremely proud of this effort that she’s making,” Wade says. “And I just really hope that some change comes from this… when I look at the little girl in those photos looking at the camera with defiance, I said to Payton, ‘That was the day you started fighting back.’”

Now, she wants to fight to ensure that what happened to her never happens again. Much has changed in the justice and child-welfare systems since 1981. But much has stayed the same, Dzikowicz says.

In the broadest strokes, the things that happened to Payton could happen to child-abuse victims today.

"Once that threat is gone, what are we doing to repair the damage and ensure that kids are safe?"-Christy Dzikowicz

“One of the biggest things we can look at is, ‘What’s our goal?’” Dzikowicz says. “What we need to realize is we can’t just stop at removing the threat. That’s where we’re at right now, but that’s what needs to change. Once that threat is gone, what are we doing to repair the damage and ensure that kids are safe?”

And when people ask Payton how she’s doing now, she smiles, and her eyelids flutter, and she says, almost to her own surprise: “I’m doing good. I really am.”

The memories have not gone away. It’s just that now, she says, they’re beginning to lead her out of the past that once haunted her, and into a sense of purpose.

“Everyone who knows me says ‘You’re here for a reason,’” she says. “I’m still working on what the reason is.

"I’m still broken. I have my good days and my bad days. But I have more good days now than I’ve ever had.”

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.