A decade of dubious deals, disquieting dollars A timeline of troubling real estate sales, purchases and developments during Sam Katz’s time in the mayor’s chair

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/05/2022 (1306 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Controversy was a frequent visitor to city hall during the administration of Sam Katz, who served as Winnipeg’s mayor from 2004 to 2014.

In recent years, the spotlight has focused on one: the Winnipeg Police Service headquarters construction project.

That’s because in December 2014 — one month after Katz left office — the RCMP raided Caspian Construction, the firm awarded a single-sourced contract on the over-budget job.

The raid revealed the existence of RCMP Project Dalton, the multi-year, multimillion-dollar fraud investigation into the construction project.

Katz, former City of Winnipeg chief administrative officer Phil Sheegl and Caspian owner Armik Babakhanians were among the key figures in the criminal probe.

This week, the Free Press revealed the existence of a second, secret RCMP investigation into city hall dealings during the Katz administration.

RCMP put Katz-era deals under secret microscope

Posted:

The discovery of a secret police investigation into a string of municipal real estate deals and a controversial capital project sheds new light on the scope of suspected criminal activity at Winnipeg city hall during the Katz-Sheegl era.

Code named Project Dioxide, it launched in the fall of 2014, and ran parallel to Project Dalton.

The investigation probed a string of municipal real estate deals from 2007 to 2011, as well as the over-budget construction of four fire-paramedic stations and an associated, aborted land swap.

In March 2015, the RCMP tapped FINTRAC — Canada’s financial intelligence unit, which works arms-length from law enforcement — as part of Project Dioxide.

The FINTRAC records obtained by the RCMP included information about electronic banking transfers connected to Katz’s and Sheegl’s financial interests in the United States — specifically, Arizona — from June 2008 to July 2010. Both investigations closed without criminal charges; Project Dalton in 2019 and Dioxide at an undisclosed date.

The revelation of Project Dioxide’s existence sheds new light on the scope of the criminal probes into questionable city hall practices during the Katz-Sheegl era, and resurfaces old questions about the two men’s relationship with Shindico, a prominent real estate development firm owned by brothers Sandy and Robert Shindleman, who are longtime personal friends and business partners of Katz.

The discovery of RCMP Project Dioxide has rekindled calls for a public inquiry into controversial and questionable city hall practices while Katz was mayor.

In order to better understand what led the RCMP to launch Project Dioxide, the Free Press reviewed the external audits — a 2013 report into the construction of the fire-paramedic stations, and a 2014 report into real estate management — that served as the basis of the investigation.

The Free Press also reviewed all relevant public record documents, including additional audits and reports, and past coverage from multiple news outlets, in an effort to pull together a comprehensive timeline of the controversies that sparked at least two criminal probes into Winnipeg city hall.

● ● ●

Thirty-one years before he was elected mayor in the 2004 municipal byelection, Sam Katz graduated from the University of Manitoba with a bachelor’s degree in economics.

Also at the U of M during those years were the men who would one day be embroiled in controversy with Katz as mayor: Phil Sheegl and Sandy and Robert Shindleman.

Following a brief stint in dental school, Katz dropped out to open a clothing store in Brandon, and in the decades to come, he found success in the entertainment business.

In 1994, he successfully brought the Goldeyes minor-league baseball team to Winnipeg. Co-investors in the club were the Shindleman brothers, both of whom served as directors.

In 1997, Katz founded the non-profit Riverside Park Management and, once again, the Shindleman brothers were tapped to sit on the board of directors.

Shindico’s business dealings with the city predate Katz’s time in office and, as far back as 2000, at least one of their deals raised eyebrows. That year, an audit into real estate practices found the city was losing money because councillors were meddling in negotiations.

In one case, councillors met with Shindico to discuss leasing a property without anyone from the public service present. The deal was later approved, and the audit found it cost the city millions of dollars more than necessary.

On June 22, 2004, Katz was sworn in as mayor. He did not place his business interests into a blind trust, nor did he step down as president of the Goldeyes or RPM. During his time in office. the Shindleman brothers provided financial backing to his campaigns.

It did not take long for Katz to be accused of mixing personal and professional business.

In July 2004, a selection committee of four councillors approved the sale of the old Winnipeg Arena to Shindico for $3.6 million, with the city agreeing to cover $1.5 million in demolition costs. All told, the city made $2.1 million by selling off the asset.

The decision was criticized by the Ontario firm Hollecrest & Associates, which had offered the city $6.2 million — paid out in four instalments — to develop the old arena into the world’s largest indoor aquatic park.

Supporters of the Hollecrest proposal questioned whether Katz’s friendship with the Shindleman brothers influenced the decision to sell the property to their company at a lower cost.

“We don’t have any special relationship with the mayor,” Sandy Shindleman said at the time.

But a different tune was sung by the chairman of the selection committee, then-Coun. Mike Pagtakhan, who conceded the optics weren’t good.

“It may look bad, because Sam and Sandy are close, but there was no influence on us,” Pagtakhan said. “It wasn’t like I was bribed or anything.”

In March 2005, Katz sold his shares in the Burton Cummings Theatre for $50,000. Months later, he introduced a motion at council to give his former business partners at the venue $220,000 in city grants. He did not recuse himself and voted in favour of the motion.

In 2006, Katz was re-elected as mayor.

“We don’t have any special relationship with the mayor.” – Sandy Shindleman

In 2008, Glen Laubenstein was named the city’s CAO.

That April, Sheegl was hired as the director of the property, planning and development department, despite having no previous public-sector experience. His private-sector background had been in the real estate and development industry. In November, Sheegl was promoted to deputy CAO.

“He’s not just a friend, but a good friend,” Katz said when Sheegl was hired. “There have been some tremendous blunders made by the city, and taxpayers have paid for those blunders. Phil has the tremendous knowledge to protect taxpayers from those blunders.”

That year, Katz found himself at the centre of another controversy.

News reports revealed that RPM — with Katz serving as president and the Shindleman brothers as directors — was locked in a financial dispute with the city.

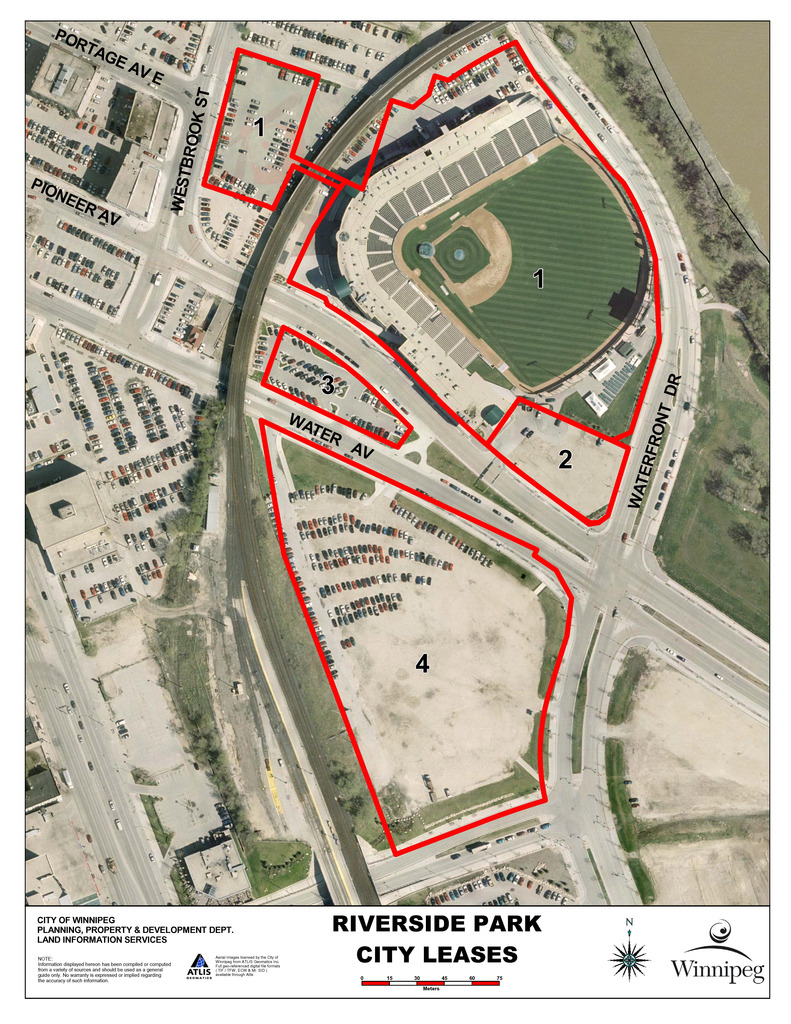

RPM was leasing land in the area surrounding Shaw Park, including a parking lot, from the city for $1 per year, plus property taxes. The non-profit then sublet the land to the Winnipeg Goldeyes — which also had Katz as president and the Shindleman brothers as directors.

In 2006, the city imposed a steep increase on the property taxes the non-profit was expected to pay, which RPM appealed. Critics accused Katz of being in a conflict-of-interest, since his non-profit was locked in a dispute with the city while he was mayor.

In April 2008, Katz stepped down as president of RPM. The Shindleman brothers remained on the board of directors.

A subsequent Free Press investigation into the controversy cited a business expert who said the arrangement between RPM and the Goldeyes was highly unusual.

By 2008, the push for a new police headquarters was picking up steam, after cost estimates for repairing the Public Safety Building jumped. That February, the consulting firm Hanscomb authored a feasibility study for the city that estimated the cost of buying and renovating the Canada Post building and warehouse on Graham Avenue at $179 million.

That was roughly the same price tag estimated for razing the old PSB, as well as a nearby parkade, and rebuilding a new police HQ on the same grounds.

In the end, the city chose to buy and renovate the Canada Post structure, despite not searching for other properties downtown that might have been suitable.

In November 2009, city council approved $30 million for the purchase of the building — without having conducted an appraisal on the property — as well as $105 million for construction costs.

The budget was $44 million less than what Hanscomb estimated was required to complete the job.

Years later — when questions were raised as to why council was presented with a budget significantly lower than the feasibility study estimate — Katz placed most of the blame on AECOM, the project’s initial design firm.

“To accommodate the Winnipeg Police Service in the Canada Post Terminal Building, it is estimated that the cost of construction for redevelopment… will be $97,534,735.” – Shindico report

But the Free Press recently obtained a second feasibility study commissioned by the city that suggests the lower price tag may have originated with Shindico.

“To accommodate the Winnipeg Police Service in the Canada Post Terminal Building, it is estimated that the cost of construction for redevelopment… will be $97,534,735,” reads the Shindico report.

A review of both the Hanscomb and Shindico feasibility studies shows that a range of necessary project elements, including soft construction costs — intangible expenses typically associated with the planning, permitting and financing of a project — were pulled out of the latter report.

The Shindico study is dated October 2009. One month later, the public service took its proposal to council for approval, with councillors left in the dark about the $179-million Hanscomb estimate.

After securing approval for the project, Shindico was then tapped by the city to serve as a broker for the purchase of the Canada Post building.

A subsequent audit questioned why Shindico’s services were needed, since Canada Post had already agreed to enter into single-sourced negotiations with the city.

Shindico received an $800,000 broker commission, which the audit determined was 68 per cent higher than the city needed to pay. After the purchase of the building, the city single-sourced a contract to Shindico to provide real estate management services at the site.

Around the same time, the construction of four new Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service stations was set in motion. The stations were to be located on Roblin and Sage Creek boulevards, and Taylor and Portage avenues.

In July 2010, council approved a budget of roughly $15 million for the project. In March, the city opened the job up to bidders as a public-private partnership (P3), which significantly limited the pool of firms qualified for the job.

But weeks later, the city changed its mind, and informed bidders the project would not proceed as a P3. Instead of issuing a new request for proposals — in order to ensure a competitive procurement process — only the firms who met the more restrictive P3 requirements were considered.

“This restrictive procurement approach can be linked directly to all contracts being eventually awarded to Shindico via non-competitive methods.” – Audit

An audit would later find that “this restrictive procurement approach can be linked directly to all contracts being eventually awarded to Shindico via non-competitive methods.”

The audit also found Shindico was repeatedly leaked inside information not available to other bidders. At one point, a rep from the company even went on a trip to Ontario with then-WFPS chief Reid Douglas, to look at possible fire hall designs before the firm had secured the job.

Douglas would later claim that before the tendering process was complete, Sheegl told him in a private meeting: “I want Shindico to build these fire halls.”

Shindico’s initial bid was $18 million, which was significantly higher than the $15 million budget city council had approved.

Concerns about cost overruns were addressed by Sheegl, who assured then-chief financial officer Mike Ruta — based on information supplied by Shindico — that the job could be done for $15 million.

According to the audit, the $15 million budget was not “based on any established construction costing methodology,” and was “largely based on representations from (Sheegl) to (Ruta).”

And despite the fact the construction had been pitched to council as a single project, the public service chose to proceed “as if there were four separate projects.”

The audit found that was done to circumvent council spending approvals.

Any contracts valued at more than $10 million would require council signoff, but by splitting the contracts up, it ensured the total value on any given one was lower than that threshold.

The contract for the Portage Avenue fire hall was then split further — one for the foundation, one for the rest of the work. All told, Shindico was awarded five contracts through single-sourced negotiations.

Most remarkably, the Taylor Avenue fire hall was built on land owned by Shindico, despite the fact the city owned land nearby that auditors said appeared suitable.

In exchange for the Shindico land on Taylor Avenue, the city agreed to transfer ownership of three properties to the real estate firm.

When an appraisal was done on the proposed land swap, the city determined Shindico would receive more than $1 million in “excess value” if the deal proceeded.

“I need some coaching boss,” wrote John Zabudney, the city’s manager of real estate, to Barry Thorgrimson, then-director of the property, planning and development department, in March 2012.

“How are we going to justify this land exchange? This deal favours Shindico by about $1.03M.”

The land swap was later abandoned, and the city and Shindico remain locked in a dispute over what the company is owed to this day.

“How are we going to justify this land exchange? This deal favours Shindico by about $1.03M.” – John Zabudney, the city’s manager of real estate

Many of the problems identified with the job were done with the full knowledge of legal services, with the audit finding the department had not “acted in a manner to sufficiently protect the interests of the city.”

All told, the legal services department had been aware of the “splitting of contracts due to a lack of council funding approval, the commencement of construction without contracts or contract authorities in place, and the construction on land the city did not own.”

The city’s legal services department was then headed up by current CAO Michael Jack.

When the project was finished, it came in more than $3 million over budget — close to the original $18-million bid by Shindico.

In 2009, Shindico was also involved in the city’s sale of the Winnipeg Square Parkade, which was called the “gold mine at Portage and Main.” The three-storey parkade is adjacent to the office tower at 360 Main St., Winnipeg’s “premier business location.”

The parkade generated $1.8 million in annual revenue for the Winnipeg Parking Authority.

Once again, an audit found no documentation justifying Shindico’s hiring as a broker on the sale, nor any explanation of their duties and responsibilities. The firm was also not made to sign a non-disclosure agreement.

The city produced two appraisals of the parkade — one that pegged its value at $24 million, and another that estimated the price tag at $44 million, given future development possibilities. The second, higher evaluation was withheld from council.

The parkade was sold by the city for $24 million, with Shindico switching sides partway through negotiations to begin working on behalf of the buyer. Nonetheless, Shindico was paid a $400,000 broker fee by the city.

That year, the city also proposed the sale of its “Parcel 4 lands” at The Forks. Again, two appraisals were done, although the deal was never completed.

The first estimated the land value at $10 million, while the second — which did not take into consideration all future development possibilities — suggested it was worth $5.9 million. Once again, the higher evaluation was withheld from council.

In 2010, Katz was re-elected.

That year, Laubenstein resigned as CAO, taking a job with Fort McMurray as their top bureaucrat. In 2014, he was fired following an external audit into that municipality’s finances and governance practices.

A news report said the audit determined “an absence of policies and procedures” during Laubenstein’s tenure had resulted in “questionable practices,” but added that “no laws appeared to have been broken.”

In May 2011, Sheegl was named CAO.

That year, the city sold the former Winnipeg Stadium site at Polo Park for $30 million to a joint venture between Shindico and Cadillac Fairview.

In 2014, the real estate management audit determined the city had leaked inside information in the stadium site deal and the proposed sale of the Parcel 4 lands. In both cases, it had been leaked to a single, unnamed firm.

In March 2012, Katz bought Duddy Enterprises — an Arizona shell company — from Sheegl for $1. After public backlash, Katz sold the company back to Sheegl.

On Aug. 23, 2012, the CBC reported Shindico was advertising city-owned land on its website, which sparked the WFPS stations scandal.

That same day, Katz bought an Arizona home — with an estimated value of more than US$1 million — from Sandy Shindleman’s sister-in-law. A loophole in the Arizona tax code made disclosure of the sale price unnecessary, and Katz has refused to reveal how much he paid for it.

In September 2012, city council ordered an audit into the WFPS stations scandal.

The audit report was supposed to be released in May 2013, but for reasons that remain unclear, it was pushed back until October.

Between July and September, Katz purchased all of the Shindleman brothers’ shares in the Winnipeg Goldeyes — officially severing his public business relationship with Shindico.

In early October, Sheegl resigned as CAO.

Days later, the audit into the WFPS stations scandal was released, followed by more damning audits in the months to come. The series of external audits were heavily criticized by Katz and Sheegl.

“Make any assumptions you want. I don’t spend a lot of time with Mr. Sheegl.” – Sam Katz

When asked why Sheegl had resigned, Katz claimed not to know.

“Make any assumptions you want,” he said. “I don’t spend a lot of time with Mr. Sheegl.”

Nov. 3, 2014 was Katz’s last day as mayor.

That month, RCMP Project Dioxide was live.

Twitter: @rk_thorpe

Ryan Thorpe likes the pace of daily news, the feeling of a broadsheet in his hands and the stress of never-ending deadlines hanging over his head.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.