Manitoba feeling weight of minimum-wage pressure

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/05/2022 (1307 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

For Desiree McIvor, a minimum-wage job meant eating ramen noodles most nights.

It meant avoiding landlords and visiting shelters for free hygiene products. It meant knowing school would eventually bring higher wages but fearing the debt it took to get there.

“A lot of times I had to choose between paying rent or buying groceries or paying utilities,” said McIvor, 34.

Now a program facilitator for a Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls family program at Manitoba Moon Voices, the University of Winnipeg grad recalls the days of juggling low-paying jobs to make ends meet.

McIvor, a spokesperson for Make Poverty History Manitoba, called the province’s minimum wage — currently $11.95 an hour — “disappointing.”

“If you’re working a minimum-wage job, you need two of them just to survive,” she said, casting her support for a minimum hourly rate of $15.

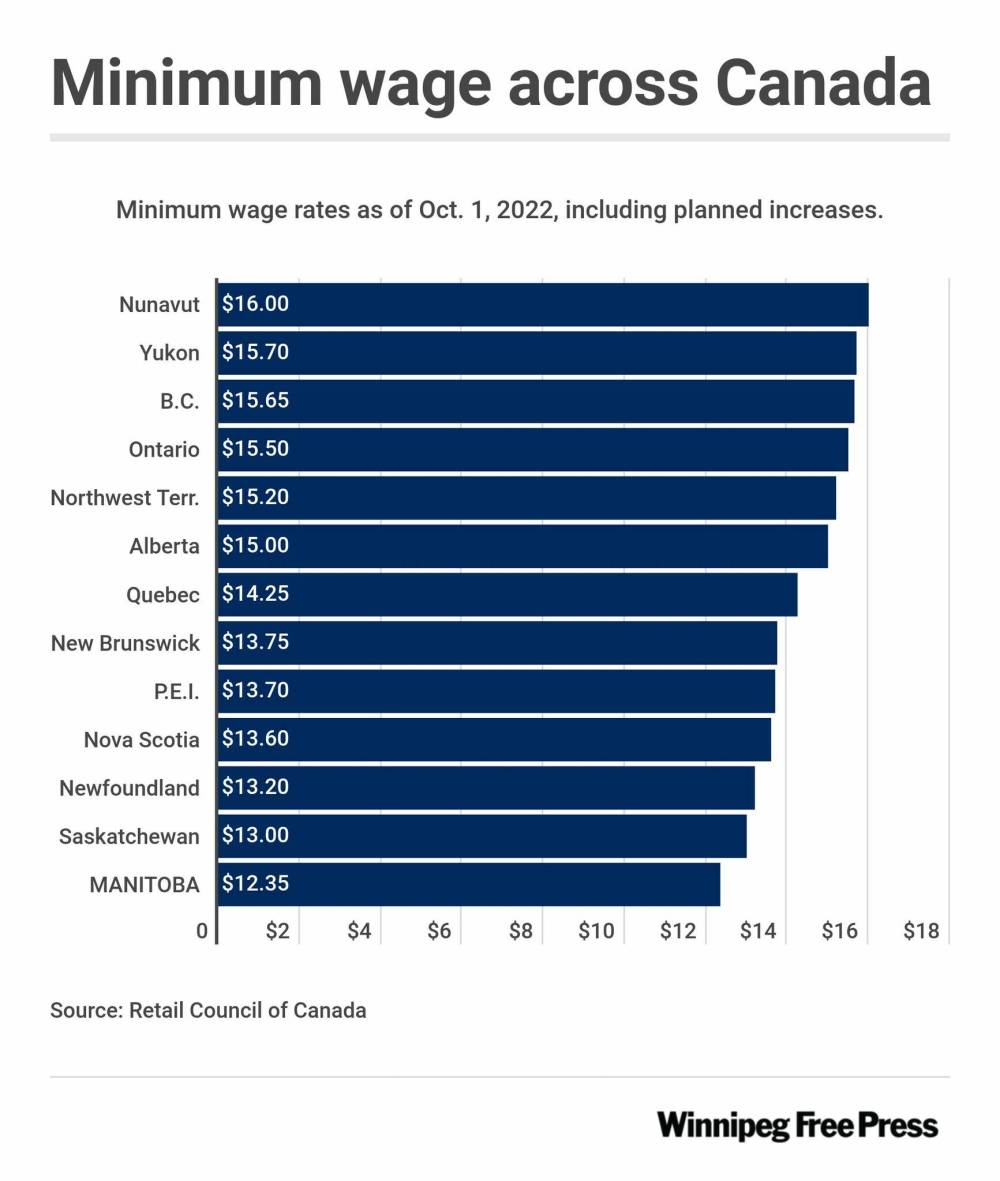

Currently, Saskatchewan is at the bottom of Canadian regions with a minimum wage of $11.81/hr. However, it will rise to $13/hr in October.

Manitoba, too, has a scheduled increase Oct. 1: to $12.35/hr. The 40-cent bump is based on last year’s annual inflation rate of 3.4 per cent. It will leave Manitoba trailing all other Canadian provinces and territories.

Manitoba hasn’t been last for at least 25 years, according to data used by James Townsend, an economics professor at the U of W.

“If we’re looking at what’s happening in Manitoba right now, the real minimum wage — so the minimum wage measured in terms of purchasing power — it’s actually decreasing,” Townsend said.

Canada’s inflation rate increased 6.7 per cent year-over-year in March. During the same time frame, Manitoba’s minimum wage increased five cents.

If it was adjusted to match March’s inflation, the current rate would be $12.70, Townsend said.

“I imagine, going forward, there’s going to be a lot of pressure on wages to go up in response to the higher inflation,” he said, adding this could also be true for people making well above minimum wage.

Premier Heather Stefanson said Monday she would consider raising the minimum wage further. The following day, Economic Development Minister Cliff Cullen said roughly six per cent of Manitoba’s workforce is paid minimum wage.

“Quite frankly, it’s a labour market. People can pick and choose where they want to work,” Cullen said.

The 40-cent increase in minimum wage will cost Silver Heights Restaurant an extra $15,000 to $16,000 annually, according to owner Tony Siwicki.

The Winnipeg business owner said he would bump the pay of his workers making above minimum wage, too, as the base wage increased, making the payroll even larger.

“We have gas prices going up and wheat prices going up and produce prices,” Siwicki said. “Everything is constantly skyrocketing at an unforeseen level, and now we add an increase to minimum wage. It’s just one more cost that our businesses have to incur at a time where we really can’t.”

Customers’ tips mean staff often take home more than the hourly rate, Siwicki said.

“When you add up all the other costs that we’re supposed to put on to the end user, how do you create a menu that is attractive to our customers?” he said. “At some point, you just can’t put everything on to the customer… You have to eat it as much as you can.”

An increased minimum wage could mean reducing operating hours or cutting back on expenses. However, Siwicki said he wouldn’t want to decrease staff because the quality of service also drops.

“If you go to $15 an hour, which (some) want to… You’re going to see less staff. I’ll cut staff back,” said Ed Cantor, owner of Cantor’s Quality Meats and Groceries.

The Winnipeg business typically starts employees at $1.25 above minimum wage, Cantor said. They get a raise after completing a three-month probation.

Cantor said he doesn’t think he’d get any resumés if he offered minimum wage in the current economy.

“Somebody’s got to pay for (wage hikes), and at the end of the day, the consumer pays,” he said. “You just can’t sit back anymore and watch the money. Your profits aren’t as much as they used to be.”

Still, it’s embarrassing for Manitoba to be back of the pack, Cantor said.

“They need to come up and pass Saskatchewan,” he said.

Many employers are offering more than minimum wage — even if they offered the lower pay pre-COVID-19 pandemic — due to the labour crunch, said Chuck Davidson, president of the Manitoba Chambers of Commerce.

“Coming out of a pandemic, nobody is in a position where they’re at sort of pre-pandemic revenues,” Davidson said. “We understand that there needs to be a balance on this. Our suggestion is that minimum wage is not always the answer.”

Instead, Manitoba should change its tax rates, Davidson said.

The province’s basic personal exemption — the amount of income someone can earn before they must pay income tax — is lower than that of Saskatchewan and Alberta.

Manitobans typically begin paying income tax after earning $10,145. In Saskatchewan, the line is $16,615, and in Alberta, it’s $19,369. Only Nova Scotia and Newfoundland have lower thresholds, according to the chamber.

Manitobans also pay more taxes than Saskatchewanians and Albertans: 10.8 per cent on taxable income up to $34,431. The number jumps to 12.75 per cent for taxable income in the range of $34,432 to $74,416, and for anything above, the tax increases to 17.4 per cent.

In Saskatchewan, an income tax of 10.5 per cent is put on workers’ taxable income of $46,773 or less. The next bracket ($46,774 to $133,638) pay a 12.5 per cent income tax.

Albertans pay 10 per cent on taxable income up to $131,220.

However, lessening an already cash-strapped government’s income will further reduce public services, countered David Camfield, a University of Manitoba labour studies professor.

“I think we need to rethink what this (minimum wage) policy is all about,” Camfield said. “I think it should be seen as a scandal that you have people working full-time and living in poverty. It’s a fundamental question of justice.”

Minimum wage has never been a living wage, Camfield said.

Just over half of minimum-wage workers are 24 or younger, according to Statistics Canada data ending in 2018. A majority — roughly 60 per cent — are women. About half of minimum wage jobs are in the hospitality sector.

There’s evidence people of colour are over-represented in such roles, Camfield said.

“The idea that it’s… almost all young people, and everybody’s working part time and so on, that’s just not the case,” the professor said. “You have a significant number of people who have either graduated from post-secondary or who have partially attended but not graduated.”

The number of minimum-wage workers is small when looking at the entire workforce but many other low-wage workers are affected by the rate, Camfield added.

“Raising minimum wage is not a magic bullet,” he said. “It’s not going to be the single solution to poverty. It’s one piece of the puzzle.”

Camfield would like to see a significant minimum-wage boost, along with a broader package of reforms such as more affordable transit and housing.

Economists the Free Press spoke with were hesitant to give an average living wage in Winnipeg because the number varies so broadly. However, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives published a commentary in 2020 stating $21.20/hr as the living wage for a single parent and one child family in Winnipeg at the time.

The Manitoba Federation of Labour has a $15 minimum-wage campaign on its website.

If minimum wage becomes too high, employers will find ways to cut positions, warned Gregory Mason, a U of M economics professor. He pointed to self-checkouts at retail businesses, as an example.

“Any time government tries to directly affect prices and wages in the economy… it usually has a range of other effects that are unpleasant,” he said.

Still, “it would not hurt, I think, to maintain parity with Saskatchewan.”

Unemployment in Canada is low — at 5.2 per cent in April — and most Manitoba companies are currently paying more than minimum wage, Mason said.

“When the unemployment rate is very low, we don’t really need a minimum wage,” he said. “When the unemployment rate starts to rise, then what you’re doing is guaranteeing a level of income to those people who can remain employed.”

He called minimum wage largely a symbolic number unless unemployment is rampant.

gabrielle.piche@freepress.mb.ca

Gabby is a big fan of people, writing and learning. She graduated from Red River College’s Creative Communications program in the spring of 2020.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.