Cleared for takeoff Royal Aviation Museum of Western Canada taking flight in its shiny new home at the airport later this week

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/05/2022 (1305 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The Royal Aviation Museum of Western Canada is ready for takeoff.

It’s taken almost four years to move its historic aircraft, equipment and trove of photographs and documents to their new home at 2088 Wellington Ave., so close to Richardson International Airport that visitors can watch planes take off and land from its observation lounge.

Arrival times

Dignitaries will be on hand for the official opening of the Royal Aviation Museum of Western Canada on Thursday.

The museum opens for annual pass holders Friday. Passes are on sale at royalaviationmuseum.com, with an earlybird price available until May 15. Adult passes are $52.50 and a pass for a family of four is $131.25. Passes for seniors, students, couples and larger families are also available.

Dignitaries will be on hand for the official opening of the Royal Aviation Museum of Western Canada on Thursday.

The museum opens for annual pass holders Friday. Passes are on sale at royalaviationmuseum.com, with an earlybird price available until May 15. Adult passes are $52.50 and a pass for a family of four is $131.25. Passes for seniors, students, couples and larger families are also available.

The public can begin visiting the museum Saturday, and tickets are $15 for adults, $12 for seniors, $12 for students 13-17 and $9 for children 3-12.

Hours are 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily. Parking is $5 per visit with paid admission, and annual pass holders receive a 20 per cent discount.

With the new home comes a new attitude, one that focuses as much on the future of aviation as its planes celebrate the industry’s rich past in Western Canada, and Winnipeg in particular.

“Right from the start we knew we were going to be providing education and inspiring next generations,” says Terry Slobodian, the museum’s president and chief executive officer.

“When I first started in this role, I met 60 to 70 of the stakeholders, everything from Manitoba Aerospace, Standard Aero, the University of Manitoba and so on, and the feedback they were giving us was, ‘You have an important role to play in the industry because you have tens of thousands of youth coming through your building and we have the opportunity to inspire them into thinking about careers in aviation or pursuing STEM-related education.’”

While the museum doesn’t officially open until next week, school groups have had a sneak peek on field trips that encourage them to pursue science, technology, engineering and mathematics, the STEM basics that must be learned before any budding pilot can take control of a plane.

New classrooms, virtual programs, a space-related play area and a learning centre complete with an airplane set up to teach visitors what makes it fly takes the museum to a new educational altitude, something Slobodian says is a must as Manitoba enters a second century of aviation.

“The pipeline of candidates to fill the various career opportunities to fuel the industry forward is not there,” he says.

While the thrill and fascination of checking out the aircraft on display remains, the museum has focused more on the stories behind them at the new facility, including courageous bush pilots who often flew in open cockpits to remote locations in frigid temperatures.

The museum also remembers the people who designed the flying machines and the crews — including flight attendants, mechanics and engineers — who continue to play critical roles in aviation.

The museum also asks visitors to submit their own aviation stories through its website royalaviationmuseum.com.

The stories the museum will tell are more inclusive, Slobodian says. New information panels and tour guides will commemorate the often-overlooked roles women and Indigenous people have played in Western Canadian aviation.

Additionally, the museum hired Niigaan Sinclair, the University of Manitoba professor of native studies and Free Press columnist, to give visitors a sense of the ways aviation affected the lives of Indigenous people.

His contributions are interwoven through the museum, Slobodian says, but are most prominent in exhibition zones that focus on northern communities.

“He was with us in the very first day when we were working on our exhibits. That was a tremendous asset because it wasn’t like we had to go back and change stuff to make it more inclusive,” he says. “Rather, right from the start, we had the opportunity to make our museum more inclusive.”

While aircraft are essential in getting vital supplies to northern communities quickly, their introduction into Indigenous societies came at a cost the aviation industry and Canadians are only beginning to recognize.

“Aviation is probably, say, 90 per cent a positive story. But airplanes flew children to residential schools and that’s a negative part of aviation,” Slobodian says.

● ● ●

The new metal-and-glass structure joins an impressive architectural array of museums in Winnipeg, and it’s a major step up from the converted hangar on Ferry Road that was home to the collection until late 2018.

The new hangar was built to fit the aircraft, rather than the other way around, and includes a reinforced roof that is strong enough to hold six suspended planes from its ceiling. That includes one of the most recognizable planes in its collection, a Canadair CT-114 Tutor that was part of the famed Snowbirds’ aerobatic squadron based in Moose Jaw, Sask.

Two large planes dominate the floor space: a Vickers Viscount airliner, which allows visitors inside to see what passenger flight was like in the 1950s when it flew; and the Junkers Ju-52, the “Flying Boxcar” that hauled goods and equipment to mining communities beginning in the 1930s.

Among the many aircraft is a new exhibit, a Canadair CL-84 Dynavert, the world’s first successful tilt-wing aircraft. It was designed to take off and land like a helicopter but fly like a plane once its wings switched positions.

Only four of them were built, and one of the two that remain is parked at the museum.

The second-floor includes the learning area and conference and banquet rooms. The museum has already hosted a wedding reception; the observation lounge is an inviting spot for photographs.

The museum’s location is vital to its future. The building will be among the first things a visitor sees when leaving the airport, and travellers with long layovers can walk to the museum from the terminal to while away a spare hour or two.

“This museum is right on the airport campus, and once we reach pre-pandemic traffic, that’s 4.5 million visitors to Winnipeg,” Slobodian says. “Every one of them has to drive past our building to leave the campus, so that clearly will provide a lot of interest for people to come and visit.”

One visitor had to bring his own fighter jet to the museum to get an early look at what’s inside. Steve Pajot has loaned his sleek CF-104 Starfighter, which the Royal Canadian Air Force flew during the Cold War from bases throughout Western Canada and Europe.

While he likes the new home for his restored plane, he’s impressed with the rest of the facility.

“I think it’s going to be probably one of the nicest museums in Canada. I’ve been to a number of museums in the States and this one is going to be comparable to any I’ve seen,” he says.

“It’s really going to put Winnipeg on the map and Winnipeg has always been known as an aviation city. Having it right by the airport is really going to make it one of the gems of the city.”

Complex choreography, precise aerobatics

It took about 18 months to turn mission impossible into mission accomplished.

They’re hanging from the ceiling

The six planes that are suspended from the roof of the Royal Aviation Museum of Western Canada:

• De Havilland Tiger Moth

• Stinson Reliant

• De Havilland DHC-2 Beaver

• CT-114 Tutor Snowbird

• NA-64 Yale

• Schweizer Glider

The task was to take six of the aircraft in the Royal Aviation Museum of Western Canada’s collection and hang them from the ceiling of its new 68,000-square-foot building.

Staff were unable to learn from other aviation museums because the COVID-19 pandemic had forced most of them to close.

Little did they know at the time that the man with the solution works at an office on Border Street, only a five-minute drive away.

“When we built the building, the architects were aware we were going to be suspending a half-dozen aircraft, so in preparation for that, they reinforced the ceiling to allow us to do that,” Terry Slobodian, the museum’s president and CEO says.

“On the other hand, no one in Manitoba had hung an aircraft before and it took us a long time to figure out how to do that and it wasn’t until we met Frank Roberts that we did figure out how to do that.”

Roberts’ engineering firm, F.A. Roberts & Associates, have used cranes many times on projects, most notably to erect curved bridge girders on the new Disraeli Freeway bridge that was completed in 2012 or to safely hoist the Golden Boy from atop the Manitoba Legislative Building in 2002 so it could be repaired.

At the museum, the first to return to the “sky” was the de Havilland Tiger Moth bush plane, a biplane that has many places to attach cables and wires.

Slobodian says it took longer than everyone thought, but Joel Nelson, the museum’s vice-president of operations and the person co-ordinating the move to the new building, said there was good reason.

“It needs to be done right and safely so these things never ever fall on top of somebody,” Nelson says. “The other consideration is these aren’t necessarily just airplanes. We’re a museum, so we designate them as artifacts.

“It would be really easy to drill a bunch of holes in the plane and put some wires in but we weren’t able to do that, just out of respect for history.”

There was nothing simple to hanging the Snowbirds’ CT-114 Tutor jet, which is suspended from the ceiling in the middle of an aerobatic manoeuvre.

“To achieve the effect the museum wanted, we had to design some frames that would be installed between sections of the aircraft to allow us to show it in the dramatic position they were looking for,” Roberts says.

That meant it was taken apart and a metal brace installed within the fuselage. New aluminum panels were fabricated and painted to match the Snowbirds’ red and white colours. The wires went through those panels rather than the originals, which are in storage.

When the other four aircraft — a Stinson Reliant, a de Havilland DHC-2 Beaver, an NA-64 Yale and a Schweizer Glider — were safely secured to the ceiling, Slobodian finally got a chance to marvel at what had been only in his imagination or in design drawings.

“Once all six were up, it was pretty amazing. We’re proud of that, because I’m not aware of any other place in Canada that has six suspended aircraft,” he says.

The next job was to get the rest of the restored airplanes into their spaces, from small pieces such as the Froebe helicopter, the first one created in Canada that took off in 1937, or the giant Vickers Viscount VC2 passenger plane, the first turbine-powered airliner to enter service in North America, in 1955.

Some planes had to be reassembled because wings had to be removed to make them fit into the storage building, so rolling them into the building in the proper order wasn’t as simple as it sounds.

“There were tons of logistics that had to be mapped out in order for us to move things into the right place safely and on time,” says Nelson, who likened it to all the preparation that must be done before painting a room. “It seems like it’s really big, but once you start putting big airplanes there it shrinks fast.”

A Junkers Ju-52 transport aircraft, nicknamed the Flying Boxcar, had the largest wing span of any aircraft in Canada when it arrived in Winnipeg in 1931, so fitting it into the new building without damaging the plane was a parallel-parking nightmare.

“It just barely fit in the hangar door and we had to do about a 50-point turn to get it around some of the columns of the building,” Nelson says. “We really had to wiggle that thing back and forth and back and forth. We cleared the columns by an inch or two.”

Starfighter restoration project fuelled by fanboy’s passion

Restoring classic cars is a fun hobby for enthusiasts who combine their automotive know-how with four-on-the-floor nostalgia.

Steve Pajot shifts the pastime into a higher gear, or more precisely, he kicks in the afterburners.

His showpiece is a CF-104 Starfighter, No. 703, a stubby-winged workhorse for the Royal Canadian Air Force during the Cold War that will be a shiny new exhibit when the Royal Aviation Museum of Western Canada opens next weekend.

”One of the biggest things you have to have is the passion,” Pajot says. “I always say that to my nephews. If there’s something you really want, if you’re passionate about it and you pursue it all your life, it may come to fruition. It certainly has for me.”

The story of how Pajot brought a rusty fighter jet from Denmark and transformed it into a museum piece has almost as many twists and turns as the plane made during its 3,600 hours of service with two national air forces.

He first fell in love with the plane as a schoolboy at CFB Baden-Soellingen, the community in what was West Germany where Canada’s Starfighters were stationed between 1961 and 1986.

The aircraft’s sound as it soared overhead — “it sounded like a wounded moose,” Pajot says — caught his attention at first, but his life changed when his science teacher arranged a visit to the base to see one up close and try out a CF-104 flight simulator.

“I got to sit in it and one of the pilots showed me how to fly it, or give me an idea and let me think I was flying it, and from that point on I was hooked on that airplane,” says Pajot, who would collect pilot’s badges and other Starfighter memorabilia while in Germany.

”I actually got to take it up and go Mach 2 and actually have stick time because, by that time, I had already got my private licence.” – Steve Pajot

When his family returned to Canada, Pajot and his father built a three-metre long Starfighter model out of aluminum that now sits in the National Air Force Museum in Trenton, Ont.

That led to a career in aviation, including 22 years as a mechanic for Air Canada, commercial and private pilot licences and being named an honorary member of 417 Squadron, a Starfighter unit based in Cold Lake, Alta.

”I actually got to take it up and go Mach 2 and actually have stick time because, by that time, I had already got my private licence,” he says.

Canada downsized its CF-104 squadrons in 1972 and sold 22 of them to Denmark, and it’s one of those Pajot rescued from the salvage yard years later. He arranged for it to be transported on a container ship across the Atlantic and a semi-trailer truck across the continent to Winnipeg

While CF-104s have built up a memorable military legacy in Canada, the one Pajot owns is like the Wayne Gretzky rookie card of Starfighters.

“The really good thing about this airplane is this is No. 703, and the Canadian Starfighters that were built in Montreal by Canadair Ltd., were numbered from 701 up to 900,” Pajot says. “Seven-o-one and 702, when they came off the production lines, they were airlifted to Palmdale, Calif., and conformity-tested by the parent company. Seven-o-three was actually the first Starfighter off the production line in Canada that flew in Canada.”

It needed lots of work though, including removing the camouflage paint Denmark used and restoring it to the RCAF’s “silver sliver” scheme. Denmark also added and removed parts to suit its needs, and Pajot found old parts to make the Starfighter Canadian again.

“When we got it, of course, it wasn’t anywhere near what you see,” he says. “It was gutted. It had no cockpit in it. I had to get another set of wings. I had to replace the landing gear. I had to get an engine for it. There was a lot to do.”

It became the centrepiece at his Canadian Starfighter Museum in St. Andrews, but the hangar it was stored in changed hands in 2021 and the museum closed last August.

Terry Slobodian, president and chief executive officer at the Royal Aviation Museum of Western Canada, has had an eye on the restored fighter jet for several years, knowing the air-show favourite would be a great addition to the new museum.

When the Starfighter museum closed, Slobodian and Pajot made a deal to find a new nest for the homeless bird.

”Much like we’ve done with a lot of aircraft in our museum, he took a wreck and he restored it into how it probably looked when it came off the assembly line in the 1960s,” Slobodian says. “It’s just a very incredible aircraft.”

It was a hot-rod of a jet in the ’60s, and a fully operational CF-104 would still be the fastest plane in Canada’s military arsenal. The Starfighter has been called “the missile with a man in it,” but it’s more commonly known as “the Widowmaker” because of its many deadly crashes.

The RCAF used the CF-104 as a nuclear-strike aircraft, and pilots had to practise flying it only 50 metres above the ground, zooming over treetops and mountains to evade radar if war returned to Europe.

“It was a dangerous mission rather than a dangerous plane,” he says.

One feature Pajot has added to the Starfighter are speakers in the plane’s fuselage to provide the trademark roar the jets made.

It added to the cost, but he’s evasive as a pilot in a dogfight when asked about how much he’s invested into the historic jet.

“I joke a lot because that’s one of the questions that inevitably is asked of me when I do tours,” he says. “My response to them usually is: ‘I’d like to tell you. If I told you, it would likely get onto social media, and then my wife would find out. And then I’d get into big trouble.’”

A 91-year-old Ghost story with a happy ending

It’s taken 91 years for the Ghost of Charron Lake to come back to life.

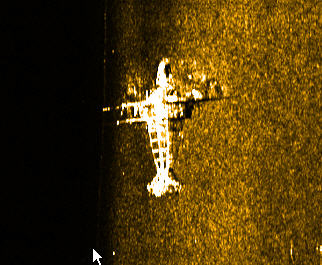

When the steel remains of a Fokker Standard Universal aircraft that last flew in 1931 takes its place of prominence at the Royal Aviation Museum of Western Canada, a new chapter in the plane’s legend — as well as Manitoba history — will emerge to amaze future generations.

The tale includes an emergency landing on a remote lake, a two-day trek to safety, a decades-long search for the plane using divers and sonar equipment and a recovery operation that required a remote-operated vehicle.

“I’m excited about it. I think it’s really wonderful,” says Pat Madden, who was part of the diving team that recovered the Ghost from 36 metres under the surface of Charron Lake in 2006.

“It was one of the biggest searches the museum had, if not the biggest, and it went on for many years, 20-some years before I got on board.”

The Ghost was registered as G-CAJD and was part of Canadian Airways’ fleet during the early years of the Great Depression. It was one of countless bush planes that had become essential parts of life in remote areas of Manitoba, the Prairies, northwestern Ontario and the Arctic.

There were risks, though. The planes were flimsier, as much of aviation technology that’s taken for granted in 2022 hadn’t been invented yet and Manitoba’s notorious weather meant there was nothing routine when a pilot roared down the runway for takeoff.

On Dec. 10, 1931, pilot Stewart McRorie and flight engineer Neville (Slim) Forrest accepted those risks when they set off for Island Lake in northeastern Manitoba, on what is today Garden Hill First Nation. They ran into bad weather and McRorie was forced to land the plane, which was equipped with skis as landing gear, on Charron Lake, about 340 kilometres northeast of Winnipeg, about halfway to their destination.

The Ghost became lodged in partially-frozen ice that was too soft to support the fully loaded plane. McRorie and Forrest camped for a couple of days but when no one came to their rescue, they walked towards the nearest settlement. They eventually made their way to safety after receiving help from Indigenous fur trappers who spotted their campfire.

When spring arrived, the Ghost sank to the lake’s bottom, where it sat for nearly 75 years.

Canadian Airways was founded by James A. Richardson — whom Winnipeg’s international airport is named after — and his son George began a search for the Ghost in 1970 after learning it was the last Fokker Standard Universal remaining in the world.

“He embarked on a mission, which later became an obsession, to hunt, to search and rescue that aircraft,” says Terry Slobodian, the museum’s president and chief executive officer.

“He (George Richardson) embarked on a mission, which later became an obsession, to hunt, to search and rescue that aircraft.” – Terry Slobodian

The museum called Madden — in 1993 he was Cpl. Pat Madden of the RCMP’s provincial underwater recovery team — and that began a painstaking search of Charron Lake that 15 years later would raise the Ghost back to the surface.

“I jumped right on it, absolutely. It was an exciting project, good training for the guys and excellent PR,” Madden recalls, adding they brought side-scanning radar to help locate the aircraft, but to no avail.

He returned in 1999 with a group that included his wife Annette Spaulding, a dive-wreckage expert, Ken McMillan, Gordon Nowicky and Bil Thuma. They called themselves the Fokker Aircraft Recovery Team for a laugh but they weren’t joking around when they arrived at Charron Lake.

They had obtained better research on where the plane might be, including oral histories passed down from one of the fur trappers to his grandchildren that proved to be helpful. They also had two types of sonar and a ROV to scan the lake bottom for longer periods than the divers could remain underwater.

Five annual trips later, they finally saw the Ghost on July 4, 2005 through a camera lens mounted on the underwater vehicle.

“My understanding, it was going to be stainless steel or a very durable steel tubing. It turned out it was just normal steel so it was very rusted and delicate,” Madden says.

The plane was eventually recovered and brought back to the museum. What remains of the Ghost today includes its steel frame, its propeller, a ski it used for landing gear and the 270-kilogram engine that tried to push the plane through the bad weather back in 1931.

“It’s going to be our most spectacular, immersive exhibit,” Slobodian says. “You’re going to think that you’re at the bottom of Charron Lake, which is how they found it.”

Madden, who retired from the Mounties as a sergeant and now lives near Dallas, will be one of the dignitaries on hand for next week’s grand opening.

He began donning scuba gear in his teens and he’s searched for sea creatures and wreckage at the bottom of lakes and coastal waters for 53 years and counting. Volunteer work, which included his role in finding the Ghost, led to being awarded the Sovereign’s Medal for Volunteers from the Governor-General in January 2020.

It’ll be the Ghost of Charron Lake, a plane that’s become an artifact, that he’s most looking forward to seeing again.

“I think it is going to be a closing for me,” he says. “It’s finally up on display, and that’s something I’ve wanted all along. I’ve wanted it to be conserved and put in a museum, as it was found at the bottom of the lake. I didn’t want it to be restored.

“For me it’s a story of survival and heroism, these two airmen, McRorie and Forrest… being rescued by an (Indigenous) fur trapper. It’s an amazing story, and I think that’s what I want to see, the focus on the story.”

Alan.Small@winnipegfreepress.com

Twitter: @AlanDSmall

Alan Small has been a journalist at the Free Press for more than 22 years in a variety of roles, the latest being a reporter in the Arts and Life section.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.