Resolve takes root among rubble Ukrainian village picks up pieces in wake of Russian occupation

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 07/09/2022 (1187 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

KYIV — A few minutes down the road northeast of Ukraine’s capital, along the big highway that leads, if you follow it long enough, to Belarus, from where the first wave of Russian troops came, the busy streets and soaring apartment blocks fall away. What grows in their place is a grassy sort of quiet: sunflower fields, pastures and copses of pine.

You can turn off the highway there, bumping down narrow pitted roads through villages that have existed for a thousand years or more. Strings of houses, many of which have been pieced together from various parts owners acquired as they could afford them and backed by sprawling gardens, heavy now with late-summer harvests of potatoes and apples.

This is a story about the people who live in just one of those houses, in the village of Svityl’nya.

MELISSA MARTIN / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

It starts like this: a mortar shell exploded on Volodymyr Lytvynenko’s home only minutes after he’d left. It blasted a hole in the earth right beside the room where he’d been sleeping, because at 62 he was too stubborn to flee when Olga, his wife of nearly 40 years, as well as their son, daughter-in-law and grandchildren had.

He wasn’t the only one in the village who had decided to stay put, in the path of the Russian advance.

“I was calling my classmate, telling her you have to leave, and sending her money,” says Svitlana Lytvynenko, Volodymyr’s daughter, who now lives in Vinnytsia (some 300 kilometres west) with her husband. “But people don’t want to leave their homes. Up until the moment you can actually die, they don’t want to leave. My dad, even knowing that, he stayed.”

”People don’t want to leave their homes. Up until the moment you can actually die, they don’t want to leave. My dad, even knowing that, he stayed.”–Svitlana Lytvynenko

But that one night in February, a few days after the war started, the booms of artillery were creeping closer and, for the first time, Volodymyr was scared. So he left the house he’d built himself over the last 26 years and descended into a clammy root cellar, sheltering amidst jars of fruit and bags of onions. Within minutes, a blast rocked his yard.

“Either I will die here or I won’t,” he thought. So he prayed, and waited for the cellar roof to collapse on his head.

When he emerged six hours later, the back half of his house was in ruin. But he was not, so he tossed his little black dog into his boxy 1986 Soviet-era VAZ sedan and fled. He escaped just a few hours before Russian troops arrived and set up their tank in front of his house. For the next 22 days, Svityl’nya was under occupation — until suddenly, it was not.

MELISSA MARTIN / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

It’s been five months since Russian soldiers retreated from the Kyiv region, and while the eyes of the world moved elsewhere — to the Donbas, to Zaporizhzhia, to Kherson, to places where fighting and death come the fiercest — residents of the formerly occupied villages near Kyiv have quietly picked up the broken pieces of their lives and tried to carry on.

That doesn’t always come easy. These are the communities where the battle for Kyiv was fought, and they still bear the scars of war the capital, for the most part, does not. Bridges blown up by retreating soldiers, leaving villages cut off from each other. Streets where almost every fence is painted with a word in large, pleading white letters: “lyudi.” People.

Here, the wreckage of war is everywhere. A tractor rests in a field, crushed like a pop can by some hideous explosion. Two civilian cars burned to husks, with a sign taped to the wreck asking people not to move them: they’re a memorial for people who died there. A village school looms empty, its insides charred black by fire.

MELISSA MARTIN / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

Then, there are the houses or what used to be houses. The house where a woman was killed and neighbours found a piece of her hair still stuck to the wall. The house where a man was burned alive. The house where Russian soldiers parked, and then intentionally exploded, their own malfunctioning BM-21 Grad rocket launcher.

That blast ruined many things in the village. It demolished the house beside it, leaving only half of its concrete carcass and a mountain of mangled metal. It shattered windows in the village for hundreds of metres and left some houses unstable. Houses built, in so many cases, by the people who live in them. Rubble and junk now, too many of them.

It is one thing to describe the destruction. It is another to see. When Svitlana returned to the village in April, she was “just completely speechless,” she says. Roads were still littered by the grisly remains of destroyed Russian tanks and infantry vehicles. She and her husband sat down and wept but her father, Volodymyr, urged them to keep moving.

MELISSA MARTIN / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

“My dad said, no, we have to work,” she says. “My dad is just used to it, because he has to work with it.”

It’s a crisp weekend morning in early September. Svitlana guides her car along the village’s roads, past where elderly women sit in front of their houses, selling tomatoes from their gardens. This commerce is crucial. Many residents here can’t afford a vehicle — pensioners earn just $150 a month — and it’s a slow bus ride to the supermarkets of Brovary or Kyiv.

The days here are quiet, familiar, mostly peaceful. The life that’s returned to the village over the last five months is “normal,” Volodymyr says with a shrug.

Well, mostly. While crews cleared houses and roads of mines, locals believe there are more in the fields. Every now and again, a tractor will hit one and an explosion will follow. Locals keep their cows out of some pastures, too.

Meanwhile, not everyone who fled the occupation has returned. Some have no home to come back to and are staying with relatives elsewhere in Ukraine. Others have opted to ride out the war in Poland or further abroad.

Ukraine’s economy has been devastated by the war, so there aren’t many jobs, and that forces some who still have a house to leave.

Still, people here are self-sufficient. They’re no strangers to finding a way to string together a living from their skills.

“He who wants to earn money, will find a way,” Olga says simply, when asked how people in her village get by.

It’s early afternoon, and Olga is whirling about her small kitchen, assembling a lunch spread with firm, practiced hands. As she works, she peppers me rapid-fire with motherly questions: what did my parents do? Am I married? Do I have children? When I tell her my mom died the week the war started, she weeps, and she wishes for me to find a good husband.

MELISSA MARTIN / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

While lunch is cooking, Volodymyr buzzes through his house and yard, cheerfully showing me where it was damaged. He’s already begun to rebuild. He points at a new wooden beam propping up the ceiling, damaged by the Grad blast; he skips to show off the new room he’s built at the back of the house, where the shell landed. Its walls rise straight and true.

What do he and Olga think, when they think about the days their village spent under occupation?

The Russian soldiers weren’t too bad, they say: they “only” killed two people. One was the security guard at the pig farm up the road who refused to let them in; the other was the man who was burned alive in his own house.

The death toll here could have been worse. It was much worse in other places of the Kyiv region.

MELISSA MARTIN / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

Mostly, locals here say, the soldiers set up shop in the middle of the village, played guitar and drank vodka. Sometimes, they would talk to the locals who hadn’t fled; the villagers trade stories about such interactions. One such neighbour asked a soldier why they didn’t leave. If they did, the soldier replied, their commander would shoot them.

Volodymyr chuckles as he remembers another story a neighbour told him. It’s sort of funny, in a surreal sort of way.

“There is a guy who is Russian, who has always been living in the village,” he says, as Svitlana translates. “They came over to him and they said, ‘We are here to set you free.’ He said, ‘Who are you protecting me from? I’m from Kursk.’ So they said, ‘Shut up, f—- off or we’ll shoot you.’”

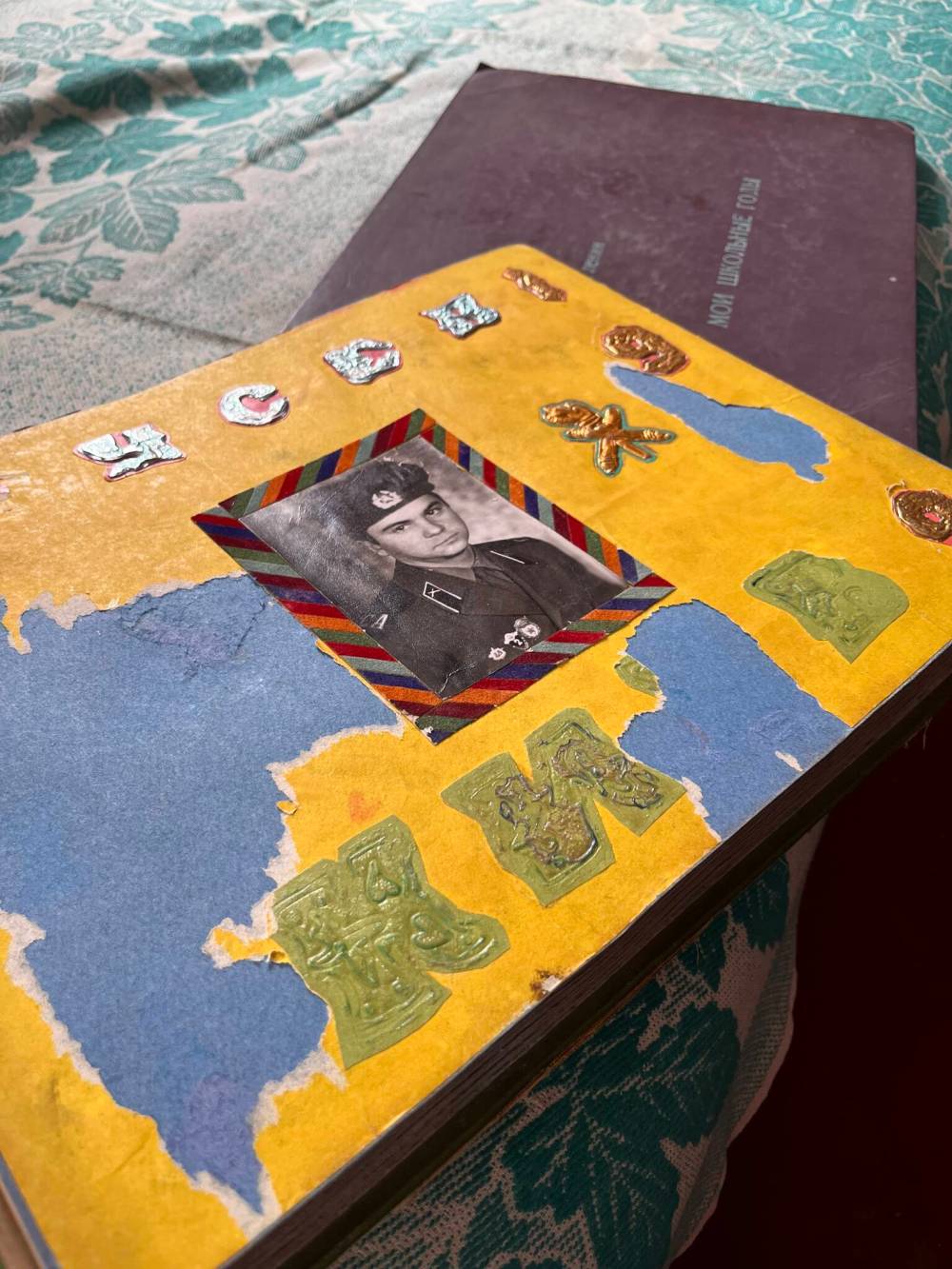

The soldiers did ransack the Lytvynenkos’ home, a fact so widespread here the couple reports it with a shrug. The first thing the occupiers found in their closet was a photo album featuring a picture of young Volodymyr, handsome in his Soviet army uniform.

MELISSA MARTIN / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

Olga wonders now if that’s why the soldiers didn’t damage their house more than they did.

They did steal Olga’s wedding ring, which was hidden in a closet. They found Volodymyr’s old army cap, and plucked the Soviet crest off the front. They also worked hard to break into the family’s safe, prying the door open and even shooting the lock; Olga cackles to think how disappointed the soldiers must have been to find the safe empty.

I think about this during lunch, over a table piled high with rye bread, cucumbers sprinkled with dill, and red peppers stuffed with fresh cheese. I begin to ask Olga how it feels to think of those soldiers in her house, going through her things; but before I can get the question out, she’s already hovering with a fresh helping of chicken and potatoes smothered in rich gravy.

“Have more, have more,” she urges.

Yet, maybe the question is answered, not in words, but in the living. Because while the occupation retreats into the past, the community works steadily to erase its memory from its land. They have made progress, though it isn’t easy. Because here we run into one of the most mundane truths about war, all wars, and who is most vulnerable to its effects.

It’s simple: many residents of Svityl’nya didn’t have much; now, they have less. Some have gotten a small payment from the Ukrainian government: the Lytvynenkos have received 800 hryvnia (about $29), and a few hundred dollars from a foreign aid organization. More cash might be coming from the local hromada, Ukraine’s version of a municipal division.

MELISSA MARTIN / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

It’s unlikely to be enough to replace everything that’s been wrecked. But the people of these villages are proud, and used to doing what they must to get by. Bit by bit, they have cleaned up the rubble and rebuilt their walls. They don’t ask for much: only enough to put back together what the war had torn asunder. They can do the rest themselves, Olga nods.

“If the government pays money, then everything will be rebuilt,” she says, firmly. “Lots of people have rebuilt who do have money, and the old people who cannot afford it, they just keep living with their relatives because they cannot do anything.”

Yet, that help can also come from far-away places — and this summer, it came in a way Volodymyr would’ve never expected.

It’s that old Soviet car of his that did it. The car had survived many things, but in the summer, the engine finally died. Without a vehicle, he couldn’t carry the family’s produce to market to earn their living or get what he needed to repair his home. Cars have always been pricey in Ukraine, even before the war.

In mid-August, his son-in-law, journalist Romeo Kokriatski, posted a little bit of his father-in-law’s story to Twitter. Within 10 days, his 20,000 followers had raised more than US$5,000 for a replacement vehicle. Volodymyr was stunned: that’s a good sum for anywhere on the planet, but it’s an especially eye-popping sum in a village like Svityl’nya.

MELISSA MARTIN / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

“He was shocked, he didn’t trust it,” Svitlana says with a laugh. “He was like, no way, how can it be? ‘People can give me money? Why would they do this? This is embarrassing, don’t do it. What if people see?’”

At home in Vinnytsia, Kokriatski wasn’t surprised by how quickly his followers chipped in with support. He’d been born in Ukraine, but grew up in New York, so he was deeply tapped into North American social media. He’d seen how, throughout this war, people from across the world had sought to find personal connections, tiny but direct ways to help Ukraine.

“There are a lot of people in the world that want to help, that want to feel useful,” Kokriatski says, chatting over a Zoom call between interviews. “I’ve gotten a lot of messages from people who otherwise feel helpless. They can’t do anything to defeat Russia any faster, and when news of a massacre occurs, everyone is like, ‘What can we do?’”

“There are a lot of people in the world that want to help, that want to feel useful… I’ve gotten a lot of messages from people who otherwise feel helpless.”–Romeo Kokriatski

Back in Svityl’nya, the day is growing long. Svitlana has to start driving back to Kyiv soon, and from there to Vinnytsia; she will take Volodymyr with her, so she and Kokriatski can help him shop for a car.

It’s a big decision. The old one doesn’t have working heat or even working seatbelts. The array of options before him is overwhelming.

“He has never had anything better than this (1986 VAZ),” Svitlana says with a laugh. “Before, we had the same car, just older. The previous one was a ‘74… He’s never had anything nice really, so he cannot choose. He didn’t sleep one night because he was choosing a car, and he didn’t know what to get.”

As we pack up to leave, Olga fusses around the entrance of her little white house. She piles tomatoes and jars of fresh apple jam into boxes to take home. She won’t take no for an answer, so I promise her I will bring the apple jam back to Canada and share it with my friends. Tears well up in her eyes; she pulls me into a hug, and kisses me goodbye on the cheek.

“We are so grateful to Canada, to the millions of people in the world who support Ukraine,” she says. “Please write that.”

We leave the Lytvynenkos’ house and pick our way along the narrow dirt paths that skirt laden gardens, plucking tart white-fleshed plums from heavy branches. Seven-year-old Anya, the Lytvynenkos’ granddaughter, announces we will play a game of chase. Her aunt has been teaching her English, and she gives each of us a role: rabbit, hunter, fox.

Then, she shouts go, and we’re off, streaking past stalks of corn, laughter ringing off metal fences shredded by shrapnel.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

MELISSA MARTIN / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

Anya, Volodymyr and Olga Lytvynenko’s seven-year-old granddaughter, pushes her baby brother down pathways that lead between houses in her village.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Thursday, September 8, 2022 9:59 AM CDT: Tweaks deck