Artifacts of invasion Ukrainian war history museum stands at threshold of past and present; part documentary, part cri de coeur

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 01/10/2022 (1166 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

KYIV — In early April, just three days after Russian troops retreated from the Kyiv region, Yurii Savchuk, general director of the National Museum of the History of Ukraine in the Second World War, rounded up a photographer and drove north, into the wreckage of communities that fan out from the capital, still littered then with mines and parts of dead people.

They were searching for something. History. Perspective. For 10 days they documented the region, taking over 1,700 photos which would eventually form a touring exhibition. But they also got a sense of the record the war had left behind, both in its objects and as inscribed on survivors’ minds. It was a record they were determined to gather as soon as possible.

Just over a month later, the museum, which sprawls over a green hillside above the Dnipro River, opened its first exhibition related to the current invasion. Others would follow, including a digital exhibit memorializing children lost to the war. Since then, the museum has hosted a steady stream of diplomats and dignitaries, and a slew of curious journalists.

Yurii Savchuk, director of the National Museum of Ukraine In the Second World War, gestures at a collection of Russian credit cards and documents found in the Kyiv region after the occupation. (Melissa Martin / Winnipeg Free Press)

What those visitors find is a striking but understated collection of objects. Most of them are mundane, some are dramatic, and a handful are famous. On the first floor, a collection of items left behind by Russian soldiers: cans of peas, thermoses, boxes of rations. A trove of Russian credit cards spread out on a transport case that once held a rocket.

Atop the case sits a passport from the separatist Luhansk People’s Republic, of a soldier who is — was? — just 19 years old. The photo attached must have been an old one; the boy in it is no more than a child. Savchuk gestures to it, with a trace of sadness. I ask him what he sees as the value of showing these items.

“I haven’t one answer for this question,” he says. “Everybody finds for themselves an answer for this question.”

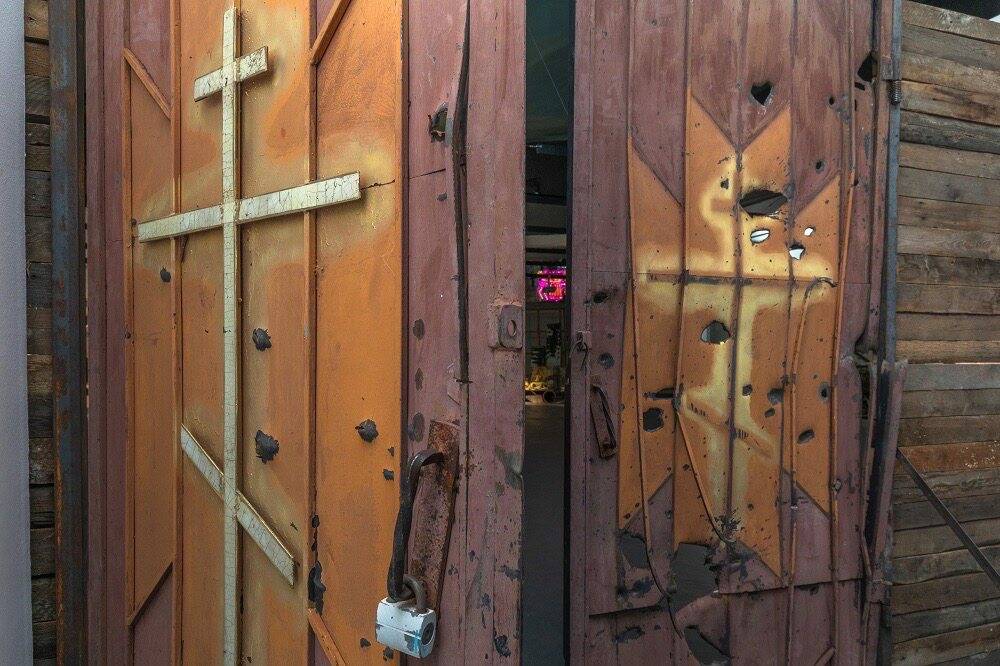

Savchuk takes me upstairs, to show me the next part of the exhibition. We enter through a heavy metal door tattered by shrapnel, which belonged to a church in the village of Peremoha — a name which, in a bittersweet twist, means “victory” — that had been blitzed into rubble. Inside are bits and pieces of religious artifacts, and something more unusual.

The entrance into one of the exhibition halls is a heavy door tattered by shrapnel. The door belonged to a church in the village of Peremoha. (Melissa Martin / Winnipeg Free Press)

In March, a video had gone viral, showing Ukraine’s forces shooting down a Russian helicopter in a particularly spectacular fashion. (It landed on a civilian’s house, destroying it; luckily, the man had left just minutes earlier and survived.) Now, the fragments of that aircraft hang in the museum, beside a video screen showing the looping record of its demise.

I remembered the video well; it had flown across Twitter. I blinked, first to come to terms with the fact that these scraps of metal belonged to that exact helicopter. By that time I had seen many such broken Russian weapons in Ukraine, but to see this was surreal: the armchair experience of observing the war as media, colliding with real life.

The fact the museum had sought this debris struck me as significant. It made a revealing statement, about how the museum — and Ukraine as a whole, by extension — is negotiating how to claim ownership of the way its brutalization plays out in the eyes of the world. It’s an exhibition in dialogue not just with the violence of war, but how that violence is consumed.

Fragments of a helicopter shot down in March. (Melissa Martin / Winnipeg Free Press)

Suddenly, another question popped into my mind. Ukraine is littered with junk like this now: Ukraine’s defence ministry claims to have destroyed over 220 helicopters since Feb. 24, along with thousands of other mechanized weapons. So how hard was it to work track this specific wreckage down?

“It was fantastically difficult, very hard,” Savchuk says — especially, he adds, given the conditions. “Because we prepared our exhibition only one month (after the war started). It was 2nd of April this region had liberation. We (didn’t) know what will be in the future. ‘Will they come back? Will they be fighting again? How long will it be?’”

At this juncture, Savchuk takes his leave — he has to prepare for a ceremony accepting a donation of archival documents that shed light on the Nazi occupation of Ukraine in the Second World War — but there’s one more exhibit he wants me to see. He leaves me with Dmytro Hainetdinov, the head of the museum’s education department, to finish the tour.

We turn into a narrow stairway, following unremarkable signs pointing the way to the museum’s ukrittya, its bomb shelter. I’m confused by this route first — there’s been no air raid siren — but as we descend and turn a corner into the dank guts of the building, the destination becomes clear. We aren’t going to a basement; we’re going into a memory.

A recreation of the Hostomel shelter contains objects collected by curators who visited the cave-like basement where dozens of civilians had sheltered for over a month in near-darkness. (Melissa Martin / Winnipeg Free Press)

When museum staff scoured the deoccupied territories around Kyiv for artifacts in early April, one of the places they focused on was Hostomel, about 30 km northwest of the capital, home to an airport that had seen ferocious fighting. It was a military community, populated largely by the families of current or retired Ukrainian soldiers.

There, curators toured a cave-like basement in which dozens of civilians had sheltered for over a month in near-darkness. They collected testimonies from the refuge’s survivors — at least one elderly woman died during those desperate weeks, as people struggled with sickness and lack of medicine — and then the curators collected the shelter’s objects.

Back at the museum they recreated the Hostomel shelter as faithfully as they could, filling their own confined underground space with its artifacts: tangled blankets, children’s drawings, a roll of toilet paper. Canned food that had been looted from shops and given to the civilians by occupying Chechen soldiers, who forced them to make videos expressing gratitude.

There’s even an old bottle of sparkling wine, custom-labelled in honour of an elderly couple’s anniversary. They had taken it to the basement with them to save it, a flash of nostalgia in a life suddenly interrupted by war. Now, it sits in a museum, lost in a chaotic assembly of mismatched mugs, threadbare mattresses and other bits and pieces of everyday life.

As we wander through these rooms, lighting the way in places with the flashlight on our phones, the walls seem to close in around us. I pause in front of the recreated pantry, gazing at jars of beets and tins of meat. Time has a way of turning such things into artifacts, but it doesn’t usually happen so fast. One day, just a can of beets at the store, but the next…

Hainetdinov nods. It’s an “absolutely different perception of a museum,” he says. Usually, artifacts are behind ropes, behind glass. But in recreating the shelter as it was and not setting it apart — making it something you descend into, as these people did mere months before — transforms it into what he calls a “live history,” an experiential documentation of war.

“It’s definitely what we cannot imagine when speaking about World War Two,” he says. “For sure, we have some residents who are still alive and can still remember the events of the Second World War. But these events ended almost 80 years ago, and right now, it is as if the ghost of the past came back to life.”

So to create these exhibitions now, when the ghosts of war are still so very alive, puts the museum at a sensitive juncture. It stands at the threshold of history and present; it is part documentation, and part primal cry. (One museum staffer tells me tour guides have become “like psychologists,” offering support to traumatized refugees from places such as Mariupol.)

“This war is not only a military conflict. This war is a conflict between civilizations: the Russian world, and Ukraine spirit,”– Yurii Savchuk

Above all, though, it is a statement about the future. Because museums are not just reliquaries for old or important things; they also assert whose histories are told. An exhibit is, on its surface, just a collection of things. But what is shown, and by whom, and how, all of that is a declaration of who has a right to hold the threads of the past, and to name them.

With all that in mind: why is it so urgent to curate the memory of a war, while that war is still ongoing?

When I ask Savchuk this question, he nods solemnly. He’s fielded this question from journalists many times.

“We understand that we are fighting against Russia not only on the battlefields, but also in the information fields, the cultural fields,” he says. “This war is not only a military conflict. This war is a conflict between civilizations: the Russian world, and Ukraine spirit. We say that we are part of the European Union, of Europe culturally, of the democratic world.”

He trails off for a moment, and then smiles, a little wryly.

“Besides, in Moscow for example, in the main Victory Museum, on 19th of April was opened an exhibition (of) Spetzyalna Operatsia Ukraine,” he adds. “So they have their view for this time, and for this process. And we show this exhibition, this installation and many different art objects. We show war.”

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.