Bold thinking created affordable housing

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/06/2022 (1365 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In the late 1940s, Canada’s post-war economy was booming, but corresponding global supply-chain disruptions, scarcity of skilled labour and material shortages resulted in skyrocketing inflation. Competition for new housing drove the real-estate market to record highs, leaving low- and middle-income tenants experiencing severe housing need across the country.

These challenges are familiar in our current post-pandemic world, and the bold action taken by the federal government back then provides a provocative point of discussion for today.

As the Second World War began, the country experienced a significant wave of urban migration, with servicemen and war workers moving to cities to be near military bases and industrial employment. This created high demand for affordable urban housing.

The federal government responded to this immediate need by creating Wartime Housing Limited, a Crown corporation that participated directly in the residential construction industry, building thousands of small, wood-framed houses across the country for military and trade workers participating in the war effort.

Employing wartime innovation and military precision in its housing development, the corporation use standardized building components and set up prefabrication facilities that assembled walls and floors to be transported to each site and erected quickly.

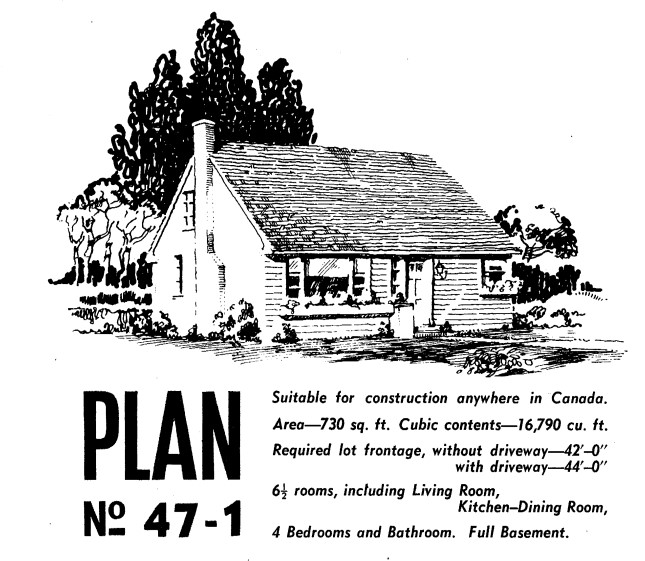

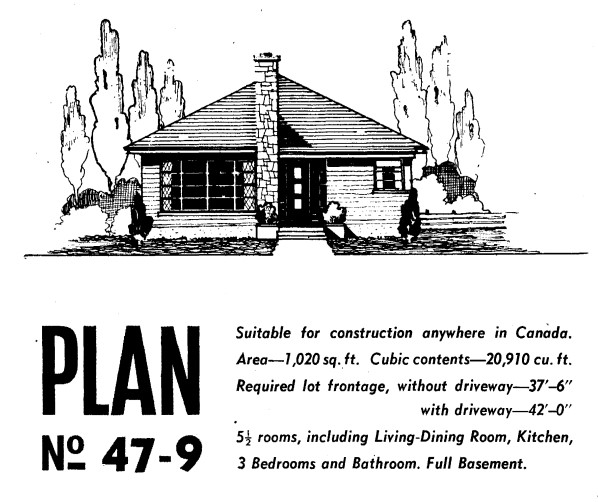

To maximize efficiency, the houses were limited to three similar designs: each had a steeply pitched roof from front to back, small sash windows, horizontal wood siding and a chimney on an end wall. To ensure affordability, the houses were kept small, ranging from 700 to 900 square feet.

The quaint little homes came to be known as “strawberry box houses,” referencing their resemblance to the shape of a fruit basket. Their peaked roofs sitting side by side on new suburban streets became a familiar image in cities across the country.

As the war ended, public pressure began mounting on the government to tackle the affordable housing shortage many Canadians outside of the military were experiencing. Wartime Housing Limited had by then developed significant expertise in building small, fast and affordable housing that could effectively address the demand. The government-built homes could be provided at a cost of about 30 per cent less than what the private market could build.

This was higher than low-income housing, but attainable for working-class people. While many Canadians were in support of expanding the corporation’s mandate, developers, construction and home builders’ associations and other private industry opposed government competition.

Many politicians had ideological opposition, fearing it would lead to the socialization of Canada’s housing industry, and despite not effectively responding on their own, local governments resisted Ottawa stepping into their jurisdiction. In the end, it was agreed that Wartime Housing Limited would continue building houses only for returning veterans and families impacted by the war.

In the seven years of the program, more than 40,000 houses would be constructed across Canada, including about 2,000 in Winnipeg.

In 1946, Wartime Housing Limited became the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), and its focus shifted to supporting private industry in the construction of affordable housing through loans, insurance and other incentives. CMHC continued to promote small houses as a key strategy for affordability.

In 1947, CMHC held a nationwide design competition called the Small House Design Scheme, and architects from across the country submitted designs, many of which were based on the strawberry box house.

Winners were published in a plan book called “67 Homes for Canadians,” with designs and complete sets of construction drawings available to be inexpensively purchased. This and subsequent books were wildly popular, inspiring the construction of hundreds of thousands of small affordable homes across the country.

To further support and normalize the idea of small houses in Canadian society, CMHC actively engaged in popular media to advertise the advantages and affordability of smaller spaces. Like the Parade of Homes today, it used marketing to establish trends in homebuilding, celebrating small home plans in popular culture magazines such as Chatelaine, Canadian Homes and Gardens and Maclean’s.

Efforts to build attainable housing in the 1940s offer some interesting points of debate in today’s context. Despite our current housing-affordability crisis, the conversation rarely moves to living smaller, as it did then. The construction of starter homes such as the strawberry box houses, which could fill an affordability gap between low-income and market housing, has essentially vanished.

The average new house today has an area of 2,200 square feet, more than double what it was in the 1970s, while the average number of people living in each house has decreased by one-third. There are more one-person households today than family households.

The average new house today has an area of 2,200 square feet, more than double what it was in the 1970s, while the average number of people living in each house has decreased by one-third.

Could this demographic shift mean the market is ready for a return to small houses constructed on small lots, built within more compact, higher density, walkable suburbs that create more sustainable cities and address housing affordability?

The concept worked in the past. The idea of government actively engaging in the construction industry to supply homes the private market cannot build on its own would face the same opposition today, but it is a radical idea to address housing need.

It’s difficult to imagine what Canada would look like today if Wartime Housing Limited had evolved into a national affordable-housing construction program offering housing security to all Canadians.

This was a lost opportunity, but it offers the lesson that the crisis of war inspired bold thinking to solve a problem — the kind of thinking that should inspire us to be as bold in our solutions today.

Brent Bellamy is senior design architect for Number Ten Architectural Group.

Brent Bellamy is creative director for Number Ten Architectural Group.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.