The snow will go on, the Obs won’t Meteorologist behind Rob’s Obs is moving weather station to Ontario

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/06/2022 (1368 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In a Winnipeg winter, there are always at least two certainties: it will be cold, and it will snow. A third certainty: the people will talk endlessly about how frigid the temperature is, and argue about how much snow is cloaking their driveways. Is it colder than it ever has been? Is there more snow today than the same time last year?

Rob Paola likely knows the answers to those questions.

Paola possesses no super powers. He is but a man with a metre stick and 40 years of professional meteorological experience, in the midst of a lifelong love affair with Mother Nature, a most turbulent mistress who rarely, if ever, reciprocates.

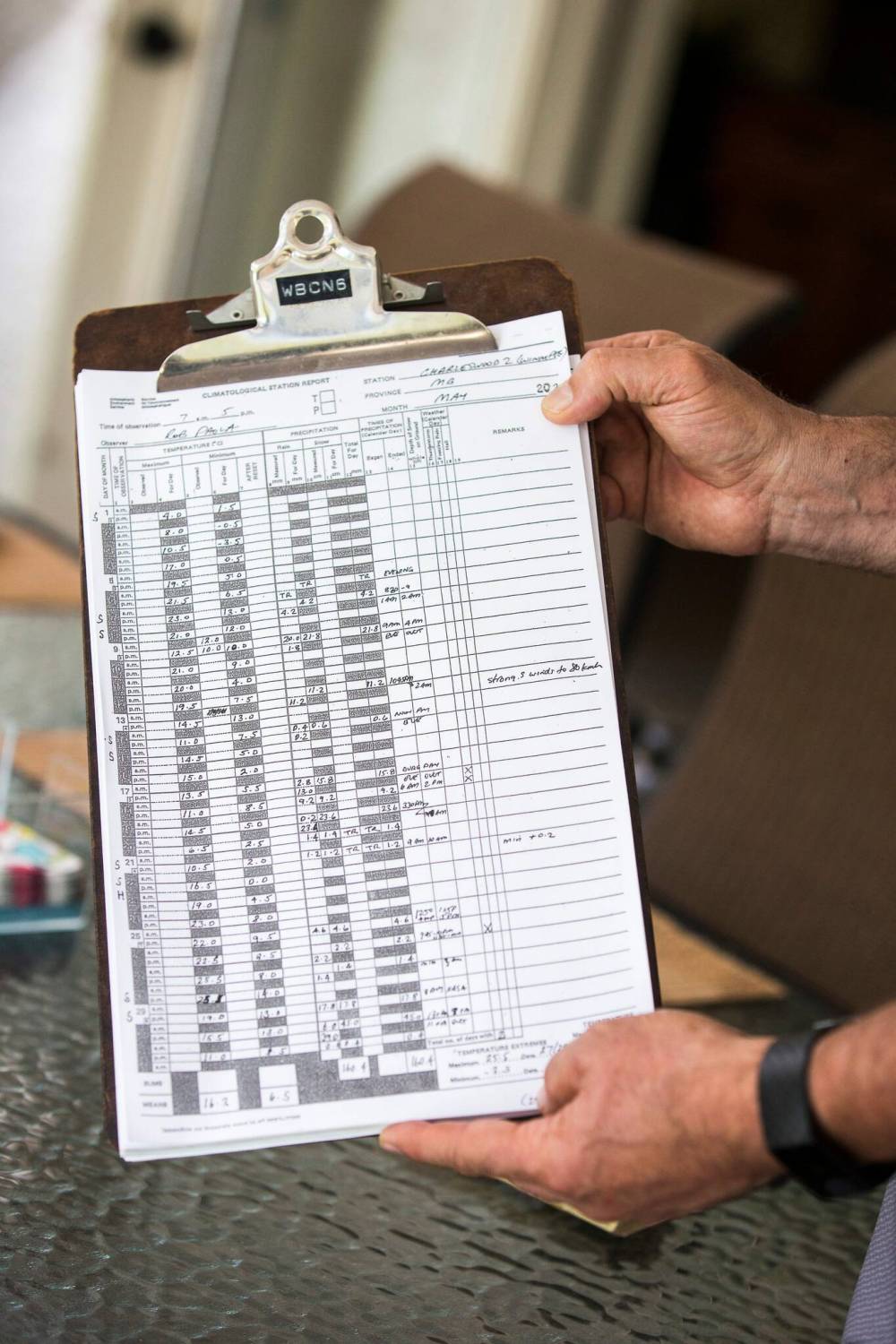

Each year when snow begins to fall, Paola heads outside his Charleswood home to figure out how much. He sticks his ruler in the ground, grabs his clipboard, and clicks his pen. In neat script, he records the temperature, what time precipitation began, how deep the powder is stacked. Then, he shares his data and insights online with thousands of followers who want a clear answer to the eternal questions: Why is this happening? When will it stop? How much snow has fallen in the city of Winnipeg?

To the third question, Paola is an excellent source of information. In truth, he’s essentially the only source. Not even Environment Canada tracks snow depth manually within the city, he said. Not since 2004. That year, the service phased out those snowfall observations in favour of automated measurements — ruler overruled. But accuracy proved difficult without a human touch, and eventually, snowfall depth measurements were phased out.

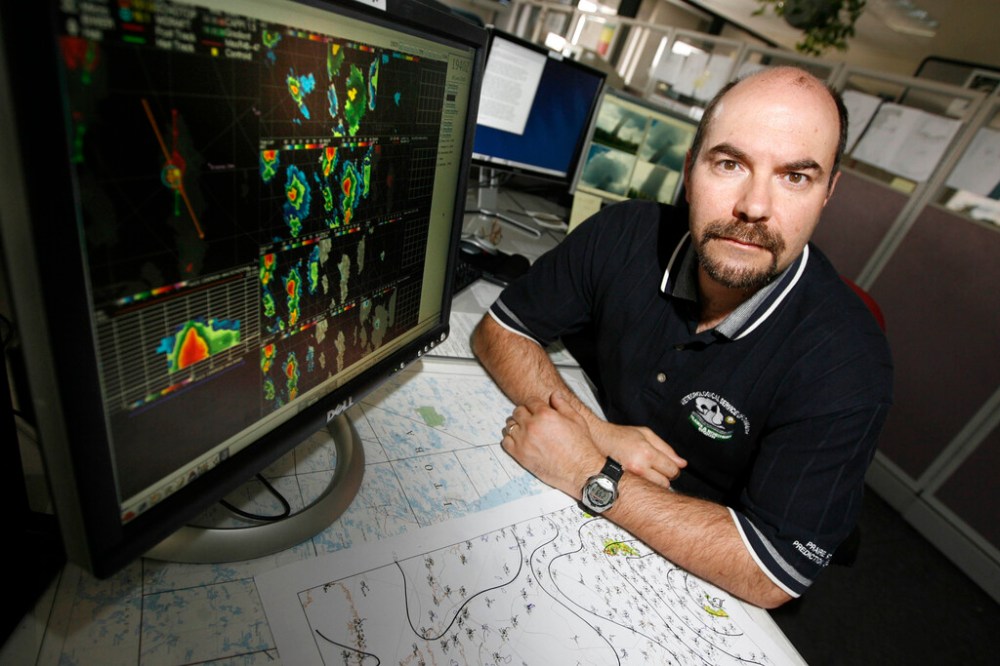

That was concerning for Paola, then a senior meteorologist at Environment Canada’s Prairie and Arctic Storm Prediction Centre. Local snowfall records had been kept since 1872, when a drugstore operator named James Stewart became the first official weather observer in the city, taking measurements for the Meteorological Service of Canada and sending them, via telegraph, to Toronto and Washington, D.C.

“I wanted to make sure we had a continuation of that snowfall observation program,” Paola said. So he volunteered to track the data himself. He grabbed his ruler, his logbook, and his pen, and he went outside.

A year earlier, Paola had started his own weather site, called Rob’s Obs. It was a pure stream of data sourced from his backyard weather station, automatically uploaded and updated every five minutes. “No discussion,” he said. “Just data.”

But when he started voluntarily collecting snowfall data, sharing it with Environment Canada and various citizen-based weather observation networks, he saw an appetite for more than just data. He began sharing historical data and interpreting the weather. What started as a meteorologist’s scientific obligation to keep the record going became a blog with hundreds of loyal readers, which soon became a Twitter account with nearly 9,000 followers hanging on his every decimetre.

Among them: golf course administrators, snow-clearing contractors, farmers, all-season cyclists, motorists, bus drivers, average folks who want to understand what’s falling from the sky. Even the weather man follows the weather man.

“Manitobans love the weather, unlike any other place in the country that I’ve seen. They want to know what’s happening,” says John Sauder, CBC’s local meteorologist, a frequent consumer of Rob’s Obs, and an occasional coffee mate of Paola’s. “Rob’s service to put out onto social media all that data has really caught the interest of Manitobans.”

This past April, when the province was bombarded, shellacked and assaulted by an unwanted snowstorm, which gave Winnipeg its third-snowiest season since 1872, Paola’s Twitter feed was as ever a must-read, although his duties hadn’t changed at all: he measured, he interpreted, he used his experience to explain what was being experienced – heavy snow in a heavy time. He sees it as a public service.

Juliet Hull, the national co-ordinator of the Community Collaborative Rain, Hail and Snow Network, a volunteer network in the U.S., Canada and the Bahamas, says the data collected by network contributors such as Paola can help citizens and communities be ready for extreme weather; with climate change, extreme weather events are more common and often more severe. “Volunteers like Rob are the backbone of organizations like ours,” Hull said.

But by the time the snow falls next, Paola will not be in Winnipeg to tell us how much.

This summer, he and his wife Jasmin are selling their Charleswood home and moving to a condo in Port Dalhousie, Ont., a beach community on Lake Ontario, not too far from where Rob Paola first was enraptured by the power of the climate.

It was January 1977, Paola was 14, and the Blizzard of ‘77 was hitting the Niagara region. “It’s the king of winter storms to ever hit there,” he remembers. “Every winter storm is compared to that one.”

It started on a Friday, and at lunchtime, class was dismissed. Out into the white Paola trudged to his house in Welland, Ont., near Lake Erie. “In every other case that storm would just blow over, but when we woke up the next morning, it was still going.”

Kids were trapped in rural schools. The radio became a lifeline. Paola’s father was working at a refinery in Port Colborne, and didn’t manage to get home until Sunday. The teenager thought the storm ended then, but on Monday morning, it was still a whiteout, winds gusting like a racecar with its brakes cut. School was cancelled for a whole week; life ground to a halt.

“That blizzard really impressed upon me how powerful Mother Nature could be,” Paola recalls 45 years later. “How powerless mankind became when facing her at her worst.”

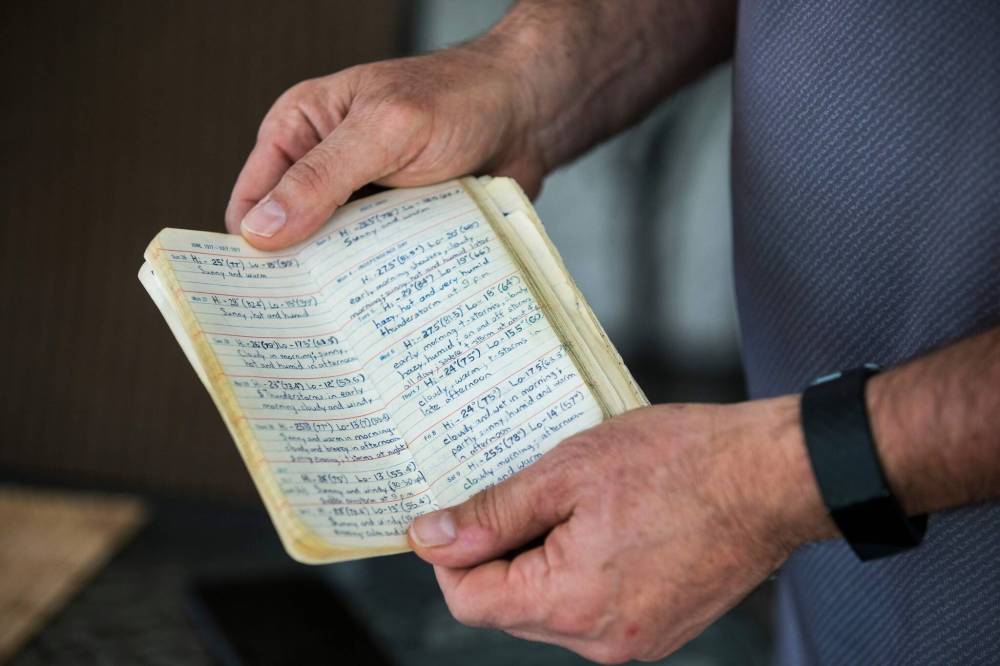

He abandoned plans for a career in architecture and soon began logging the weather in a lined journal he still has as a 59-year-old man. “Hi – 25 degrees (77) Lo – 15 degrees (59),” he wrote in lowercase on July 26, 1977. “Sunny and warm.”

He set up his first weather station: a few thermometers and a rain gauge that Environment Canada sent him after he requested it in a letter sent to the national headquarters in Toronto.

By 1981, Paola was enrolled at the University of Toronto, studying science, before transferring to McGill University. After graduating, he applied for work with Environment Canada and was hired as an intern in the meteorological training course. His first full time posting was in Winnipeg in 1986. A transfer to Toronto reconnected him with Jasmin, a former classmate and fellow meteorologist. Marriage was in their immediate forecast.

In 1997, Winnipeg had the storm of the century. In 1998, the Paolas arrived and settled. Two decades later, both are retired. But for a meteorologist, there is no escaping the subject matter of one’s career: a weather person is always a weather person.

On May 31, Paola took his final measurements from his Charleswood 2 station, announcing his impending departure from Winnipeg on Twitter. The news was received with mixed feelings. Mostly gratitude, but a fair amount of sadness. “Manitoba has lost one of its greatest meteorologists,” said Scott Kehler, president and chief scientist of climate data company Weatherlogics.

Paola will continue tracking data in his new home, but has mixed feelings over leaving Manitoba, and its unusual climate to which he grew accustomed. He will miss the sunshine, and the long summer days when it stays lighter later than seems scientifically possible. He’ll miss the wide-open blue Prairie skies, less dotted with clouds than the air above Lake Ontario.

“I won’t miss the winters,” he says.

ben.waldman@winnipegfreepress.com

Ben Waldman is a National Newspaper Award-nominated reporter on the Arts & Life desk at the Free Press. Born and raised in Winnipeg, Ben completed three internships with the Free Press while earning his degree at Ryerson University’s (now Toronto Metropolitan University’s) School of Journalism before joining the newsroom full-time in 2019. Read more about Ben.

Every piece of reporting Ben produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.