When the river became a sea From the legislature to fishers on Lake Winnipeg, the Flood of the Century affected virtually everyone living in the Red River Valley

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/04/2022 (1319 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

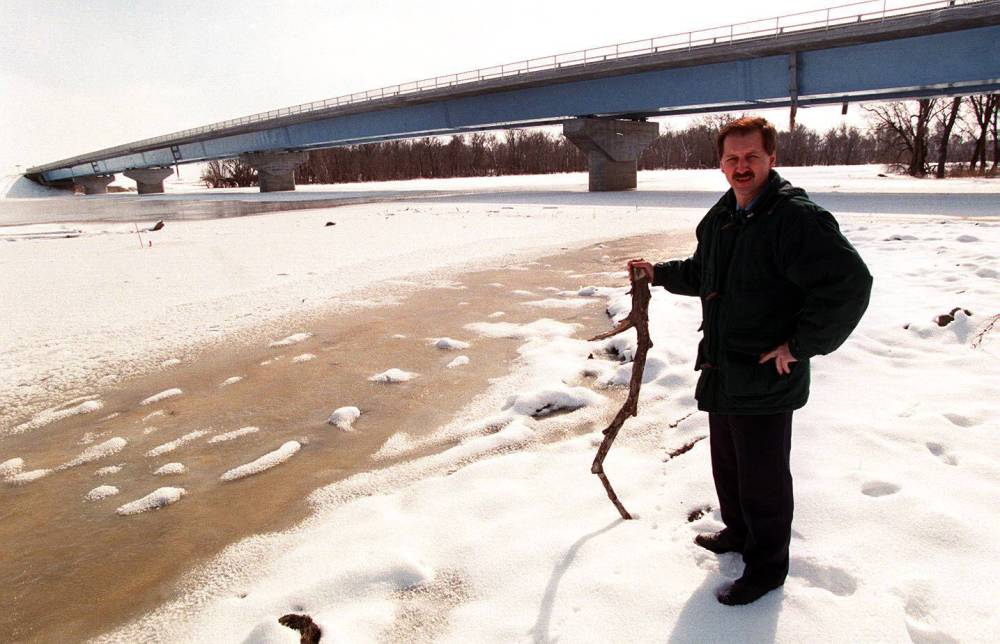

Robert Kristjanson is no stranger to water.

He’s been fishing Lake Winnipeg for about 70 years; his family has been on the lake for more than a century.

But 25 years ago, Kristjanson and his son, Chris, were plying their fishing yawls on a different body of water, the temporary but freakishly large expanse in southern Manitoba that became known as the Red Sea.

When the Red River spilled its banks in April 1997, ushering in what became known as the Flood of the Century, the pair loaded up their boat to help Manitobans who were frantically trying to save their homes.

The Kristjansons, fishers by trade, had become the operators of a water taxi over land usually tilled by tractors.

They spent more than a month helping out families in the Red River Valley before returning to more familiar surroundings.

“I had never seen the land (under the floodwater) before, and I wish I had,” Robert says, explaining the reason for frequent damage to the boat.

“We lost propellers. Everything we (could) break, we did. I wish I had known where the creeks were, it would have made it easier. The army were in rubber boats. But you can’t go over a fence with a rubber boat.”

● ● ●

The 1997 Red River flood was the worst to hit southern Manitoba in 145 years.

Before the month-long flood was over, nearly 350,000 acres of farmland was submerged, approximately 350 farmers were affected and about 25,000 residents — 7,000 of them in Winnipeg — were evacuated from their homes.

The river peaked in the city on May 3 and 4.

The Red Sea was a massive body of water — 20 kilometres wide at the American border and about 40 kilometres wide just south of Winnipeg — spreading at will across the valley’s flat farmland.

Before it was done, about 8,500 members of the armed forces were deployed here, the biggest Canadian military operation since the Korean War.

The historic flood triggered close to a billion dollars in spending for mitigation, notably increasing the capacity of the floodway, but make no mistake — the Red River will flood in the future.

Manitobans are currently getting a reminder of the river’s volatility following back-to-back weekend snow and rain storms. And more uncertainty is on the horizon; in 1997, few people were factoring in the impact of climate change.

● ● ●

Much like with cooking, there is a recipe Mother Nature follows when creating spring flood conditions along the Red River.

It starts with a wet autumn, leaving soil saturated across southern Manitoba, North Dakota and Minnesota. It’s followed by a dash of above-average snowfall during the winter. Mix in an unseasonably warm spring, with above-zero temperatures both day and night to create a rapid melt, and toss in a late-season blizzard or excessive rain and the conditions are perfect for a flood of some magnitude.

Because the ground is saturated, there is nowhere for moisture to go other than overland, to the nearest creek or river.

Those conditions created the perfect storm in 1997. The previous year was wet — 1996 is the third-worst Red River flood on record — and an early April snowstorm walloped the region. The water came as the temperatures rose, leaving a trail of destruction in North Dakota as it moved northward.

In 1997, Wayne Arseny was the longtime mayor of Emerson, the town steps from the U.S. border. Arseny, now the municipality’s tourism co-ordinator, said the apocalyptic scene that played out in Grand Forks the week before — the city’s dikes failed and parts of the downtown were ablaze — put his community on high alert.

“It seems like yesterday and I remember how we felt,” he says. “Gross panic about what was coming.”

His community hastily added more flood protection as the crest approached on April 27. A kilometre-long plywood dike was erected on the south side of town; a short time later floodwaters were lapping against it.

“It was a pretty big lake on the other side. You looked south to St. Vincent (Minn.) and Pembina (N.D.) and you saw water. I think we put it up in a day-and-a-half. We worked around the clock.

“It was monumental.”

● ● ●

From Emerson, the floodwaters headed north and soon enveloped the town of Morris. Ralph Groening, a first-time councillor for the RM of Morris, was worried. But not about his own place, more than 20 kilometres west of the river.

But deciding to err on the side of caution, Groening built a sandbag dike around his house.

“I was home at the time and I could hear the water coming,” he says. “The water came from the west not from the east. There was so much snow that year and a wet fall. It flowed over roads and it was relentless.”

His house became the first one flooded in the valley and he was the first Manitoban forced from his residence — a victim of overland runoff, because the water had no place to go. At one point, he had more than a metre of water on his fields.

Today, Groening is reeve of the municipality. He was deputy reeve 25 years ago and is proud of a decision council made at the time.

“We, as a council, decided we could purchase mobile homes (and) we purchased lots of them,” he says. “We said while (area residents) replace their house they could stay in a mobile home. That way they didn’t have to leave the community.

“I spent that summer in one. Thirty-five homes were inundated, but people lived in the trailers and went on with their lives.”

As flooded houses were fixed, people moved out of the mobile homes and the municipality sold them, he says.

As for his house, Groening dug a new basement a few metres away and had his home moved onto it. It now sits on a mound high enough to keep it safe from future floods. The work was covered by a provincial support program.

“The basement was destroyed. The water was up to almost the main floor.

And, perhaps surprisingly to city folk, Groening said while his and other farmers’ land was inundated, it was a good farming year. “As soon as the water came off, the soil was firm and hard. There was a lot of work that spring.”

● ● ●

The river still hadn’t crested in Ste. Agathe when its defences fell. A rail line, acting as a natural dike on the town’s west side, was breached and within a few hours the town’s buildings were flooded.

But by then, Nicole Sorin was already gone.

Sorin, along with her two sons, a three year old and a newborn, had evacuated to her mother’s place in St. Norbert while her husband, Jean, stayed to help sandbag homes. Within days, she was on the move again — to another family member’s home in Winnipeg — after city officials ordered the evacuation of St. Norbert.

“I had my second son on March 9 and we had the big storm about four weeks later,” Sorin says. “We were snowbound and there was a little bit of a worry about flooding. Then we were told it was going to be a higher-than-normal flood year.”

That’s when she began moving stuff from their basement to the main floor. Each dire flood forecast meant adding more items to tables and countertops.

Sorin says she was safe in Winnipeg when she saw the news Ste. Agathe had flooded.

“I saw video showing water everywhere,” she says. “That’s when I knew our house was done.”

When they finally were able to check, there were signs the water had reached their main floor.

“We rebuilt the house,” she says. “My husband did the work himself. He did a good job — the house has been bought and sold a couple of times since then.

“We were able to replace the necessities — and I didn’t lose the personal stuff. But I remember going around the town and there were just piles and piles of damaged couches and other stuff outside. It was everything in basements.”

Claude Lemoine is now president of the Ste. Agathe Community Development Inc., which was created in the flood’s wake to rebuild and revitalize the community.

Back in 1997, Lemoine was one of the dozen residents who were chosen to stay behind to monitor the dikes and pumps after the community was evacuated.

“I was born and raised in this community,” Lemoine says. “You kind of know when it is a year when you should be concerned. And the big storm before? The snow was so wet you could see the blue in it. It was very, very heavy.”

Lemoine worked for Canada Border Services and was given time off to help with the flood fight. He was doing just that on the evening of April 28.

“It was a huge disappointment felt by many. I still feel the same way, wondering if there was something we could have done differently. I don’t know. But the community really rallied together to help everybody rebuild.”– Claude Lemoine

“It was 9 to 10 p.m. and what we were told was there was a heavy flow coming. We had been starting to plug some culverts when they said the water was starting to come — we realized we needed to leave. We could hear the rumbling. We started gathering all of our people by the bridge; it’s one of the highest areas of town.

“Then we drove across the bridge, went to Deacons Corner, and then drove to Winnipeg.”

Lemoine says there was almost a metre of water throughout the community.

“It was a huge disappointment felt by many,” he says. “I still feel the same way, wondering if there was something we could have done differently. I don’t know. But the community really rallied together to help everybody rebuild.”

Lemoine says when provincial officials wanted to put in a permanent barrier, the community development organization got together and successfully got the ring dike extended, leading to the creation of new subdivisions on the north and south ends of the town as well as an industrial park, all within the expanded protected area.

“We wanted room to grow,” he says.

“We’re thriving now compared to pre-flood. We’re in dire need of another development because there are no residential lots left to build on. And the dike was built to 1997 (water level) plus two feet and now we’re hearing the province is looking at raising it even further.”

● ● ●

Slightly north of where the LaSalle River meets the Red in St. Norbert, Bob Roehle and his wife Judy were concerned about both the home they bought in 1971, as well as the rental property they owned next door perched almost on the riverbank.

“It was just a shack when we bought it. The church next door built it so a priest who was unwell could live there until he died. When we bought it we upgraded it so someone could live there 12 months of the year. Only when we went to get permits, and they couldn’t find the property, they told us to ‘do the work and don’t tell us.’”

Roehle and his wife also attached a deck to the rental house. And, years later, it was that deck he was looking at just before St. Norbert was evacuated.

“I thought maybe I should tie the deck to a tree, so I did,” he says.

“After the evacuation, I saw the chain had made a huge gouge in the deck. That’s when I realized if I hadn’t chained the deck to the tree the whole house would have gone down the river.”

A sandbag dike was built within a metre or so of the back of their house and on either side in 1997.

This year, while the flood protection around both homes is better than it was then, Judy is eyeing the Red with unease.

“We’re looking at the weather and we are feeling nervous right now,” she says.

Roehle adds: “my wife thought of moving after 1997, and every spring she thinks about it.

“But we are still here.”

● ● ●

Provincial forecasters were issuing flood warnings for months, then-premier Gary Filmon recalls, but the April blizzard and the destruction unfolding south of the border turned possible scenarios into sobering reality.

Filmon remembers clearly a scene that played out during a cabinet meeting in the first half of April.

“(Senior flood forecaster) Alf Warkentin was probably the most knowledgeable and highly respected for his forecast ability,” Filmon says. “He told cabinet we were going to be requiring the passage of the Emergency Measures Act. That allowed (then-prime minister) Jean Chretien to send soldiers here and there were 8,000 of them at one point.”

Filmon, a former civil engineer, points to two engineering marvels that helped save Winnipeg in 1997: former premier Duff Roblin’s vision following the devastating 1950 flood that led to the creation of the Red River Floodway, and the temporary construction of the Brunkild dike, which was hastily built after a hydrologist realized Winnipeg’s southwest flank was under threat of the water accumulating in the La Salle River basin.

The 24-kilometre long Brunkild dike was constructed on existing roads, leading to its distinct Z shape when seen from the air.

“It was a fantastic achievement,” Filmon says. “It took only eight days to move 900,000 tonnes of earth. And the dike did serve its purpose. During the first two days after completion, south winds were foremost, and that’s when they decided to put old school buses there because it was subject to erosion. And the water came up within two feet of the top.”

And Filmon says Roblin’s floodway was relied on even more than expected.

“The recommendation to expand the floodway was because in 1997 it was actually operated beyond its design capacity for 10 days,” he says.

“There’s no playbook for a natural disaster. You’re faced with it and you have to deal with it. And the public emergency crisis brings out the best in people, but also the worst. But they are far outweighed by everyone facing the challenge.”

”There’s no playbook for a natural disaster. You’re faced with it and you have to deal with it. And the public emergency crisis brings out the best in people, but also the worst. But they are far outweighed by everyone facing the challenge.”– Former Manitoba premier Gary Filmon

Then-Winnipeg mayor Susan Thompson also recalls the teamwork from everyone: politicians, soldiers, bureaucrats and ordinary citizens.

“Everybody simply pulled together,” she says. “We were going to save our city.”

But until the crisis passed, “I think my heart was in my throat for 28 days.”

It was Thompson who insisted that the military, under the guidance of Brig.-Gen. Rick Hillier, be front and centre as the flood fight raged on, including beginning their deployment during the day, not the middle of the night as originally planned.

“They said they didn’t want to make people nervous, but I knew people were exhausted and the military was coming in to help — they want to see them. We wanted to give citizens hope,” she says.

“It was a huge boost (to show) that we stood a chance.”

For the military, still reeling from 1993’s Somalia Affair, during which Canadian soldiers participating in a humanitarian effort tortured and killed a teenager, the flood fight in southern Manitoba couldn’t have come at a better time. Thousands of Winnipeggers lined downtown streets to give the troops a rousing sendoff weeks later, allowing the Forces to turn the page on a dark chapter.

Thompson says there were numerous contingency plans in play but, thankfully, never had to be put into action.

“One of the worst-case scenarios was for (Assiniboine) Park,” she says. “They had a plan to get the zoo animals out. Know what it was called? Operation Noah’s Ark.”

● ● ●

Every day, for weeks, Mark Bennett would descend the basement stairs at the city hall to where the civic emergency operations nerve centre was located. Bennett, the city’s emergency program co-ordinator, had recognized by mid-February that major flooding was coming.

“I asked that question every day — why did a flood-prone city put its emergency operations in the basement?” he says with a laugh.

“If the primary dikes failed there would have been 13 feet of water above my head.”

Bennett, who now lives in Calgary, credits Thompson for immediately understanding the need to shift numerous civic staff from their regular duties to begin working on flood-fight preparations.

“The head of the purchasing department gave us one of his best people and I think that person called every place in North America to get sandbags,” he says. “That was good because we filled eight million sandbags.”

“Since then I’ve said when you have an emergency everybody gets involved, from saints to sinners.”– Mark Bennett

Bennett says 1997 marked the first time since the floodway was constructed that its Rule Two was used. Rule One says when the floodway is used it should only back up water upstream to the point it would have been without a floodway.

“Rule Two is you use the (floodway) gates to keep a constant water level in the city so you don’t let it rise to the top of the primary dikes,” Bennett says. “This puts properties south of the floodway at greater risk, but it’s a balance of tens of houses versus thousands of houses to protect.”

All sorts of people volunteered to help, from high school students to members of the Church of Latter Day Saints, to inmates at Stony Mountain penitentiary.

“I think they thought they could get a day pass to help,” Bennett says. “We dispatched trucks with sand and shovels for them to fill sandbags.

“Since then I’ve said when you have an emergency everybody gets involved, from saints to sinners.”

● ● ●

In 1997, Blair Graham was a lawyer who had volunteered for several years with the Canadian Red Cross. He admits he didn’t know what he was getting into when he agreed to chair a committee of charitable and non-profit organizations rallying to help Manitobans.

There was a lot of help to be given. Thankfully, there was a lot of help to give out.

“Money started pouring in very quickly,” Graham says of the contributions from people across the country keeping track of the drama unfolding in Manitoba.

“Especially when there were very dramatic pictures of what was called the Red Sea… ultimately, about $25 million to $26 million was raised just for the Red Cross. It was an enormous outpouring of generosity.”

Graham says the committee, made up of representatives from other organizations, including the Mennonite Central Committee, United Way of Winnipeg and the Salvation Army, was set up to ensure there was no duplication of the help being given.

Very quickly, Graham realized what needed to be done.

“The Red Cross said the people will know best what they need and we will have criteria, but we will give them money… I remember one family was given a cheque for a few hundred dollars — less than a thousand — and a woman wrote back saying, ‘Thank you very much, but we only need $540, so here is a cheque for $300 to make sure the money goes to someone else who needs it.’”

● ● ●

Jay Doering is the University of Manitoba’s associate vice-president (partnerships), but in 1997 the hydraulics expert was associate head of civil engineering.

Doering says the province, Red River Valley residents and municipalities have made many improvements to flood protection since the hard lessons of 1997.

Improvements made, more to come

Manitoba Infrastructure’s assistant deputy minister Russ Andrushuk said the province learned from the 1997 flood.

“There has been a huge improvement over what we had in 1997 — it truly is a significant improvement,” Andrushuk said.

The improvements include:

• Expanding the floodway to protect the city to a one-in-700-year flood by more than doubling its capacity from 1,700 cubic metres per second to 3,964.

• All new structures in designated flood areas along the Red River have to be flood-protected for one-in-200-year floods.

• Properties protected after the flood were at 1997 level plus two feet, but since 2015 the requirement is the 1997 level plus 3 1/2 feet, to protect against a one-in-200-year flood.

• The province has spent $84 million to raise Highway 75 to meet 2009 flood levels. As well, northbound lanes from St. Jean Baptiste to just south of Morris have been raised 1.2 metres.

• Flood-risk maps have been created or are still in development to show where protection has to be raised.

• Construction on the Lake Manitoba and Lake St. Martin outlet channels is targeted to begin sometime this year or next.

But climate change has amplified the uncertainty of what the future is going to look like here.

“The floodway design was originally based on 1900 to 1950 (conditions), but the last 50 years have been wetter,” he says.

“As our climate changes and challenges us, we have to keep an eye on statistics. Is it a one in 700-year floodway or a one in 500-year floodway? The larger the floods here, the later they occur. The 1826 flood was rather late, like May or June.”

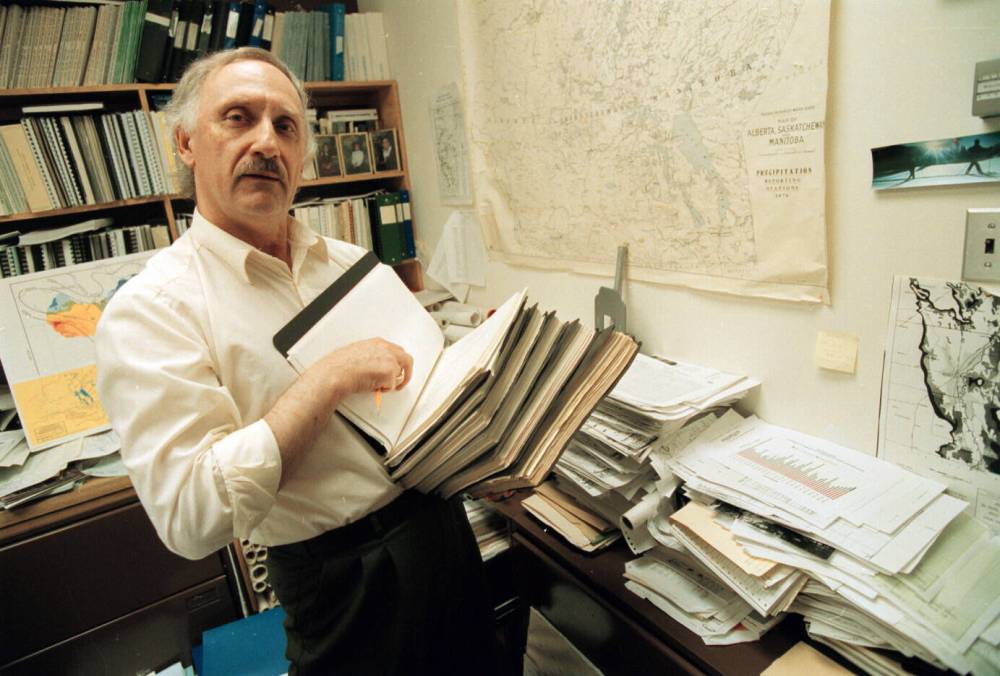

Danny Blair, a professor in the University of Winnipeg’s geography department and the co-founder and co-director of the institution’s Prairie Climate Centre, says scientists were already talking about climate change in 1997 “but it wasn’t as high-profile then as it should be now.”

“Climate change won’t alleviate the flood problems,” he says. “Snowmelt floods will always be here. We might have more change from year to year, but shorter winters doesn’t mean no floods.”

Blair says there will continue to be some winters similar to the one we just endured.

“Extremes are becoming an important concern here and around the world,” he says. “Normals are fine (but) it is the non-average conditions that are not fine… there’s a lot of surprises we don’t know how climate will have. We must be vigilant.”

Blair says engineers working on flood protection know things are changing.

“They used to just look to risk based on the past. Now the engineering community looks forward and looks to see what they need to be prepared for.”

● ● ●

After the water receded in 1997, Slobodan Simonovic, an engineering professor teaching at the University of Manitoba, was one of five Canadian representatives chosen by the federal government to be on the International Red River Basin Task Force.

Three years later, the task force released The Next Flood: Getting Prepared to provide guidance to governments on floods of 1997’s magnitude or greater.

“I’m an engineer. I have no problem teaching people how to make a dike, but this experience opened my view on how people experienced it,” says Simonovic, now a professor at Western University in London, Ont.

The report, which had 51 recommendations, concluded the floodway needed to be expanded because “under flow conditions similar to those experienced in 1997, the risk of a failure of Winnipeg’s flood-protection infrastructure is high.”

The task force also said “flooding is a fact of life along the Red River. The disastrous flood of 1997, while a rare event, was neither unprecedented nor unforeseen… flood preparedness must be part of the culture of the Red River Valley.”

Simonovic says the task force surveyed people on both sides of the border on three separate occasions to assess the evolution of their thoughts as the crisis faded into the distance. Initially, affected residents said they needed help from government and engineers. The second time, they said it had been difficult, but manageable. By the time they spoke a third time — four years after the flood — many felt concerns were too high.

”(The Red River Valley) is at the bottom of an ancient lake. If you live here you need protection.”– Slobodan Simonovic, engineering professor teaching at the University of Manitoba

“I also found very clear differences between behaviour on both sides of the border. Here, Canadians expected the help of the government and engineers who deal with the feds. Across the border, even with people who had lost homes, it was personal responsibility. They didn’t expect people to come help because they felt it was their fault because they chose to build a house on the bank of a river.”

Simonovic says the need for flood protection in the Red River Valley began centuries ago. “It is at the bottom of an ancient lake. If you live here you need protection.”

Warming winter temperatures and earlier snow melts reduce the possibility of flooding, he says, but changing temperatures also bring more moisture.

“It’s hard to say if the current infrastructure is good enough to deal with it,” Simonovic says.

“There’s no historical record of both the Red and Assiniboine flooding at the same time, but that is one potential event that may happen.”

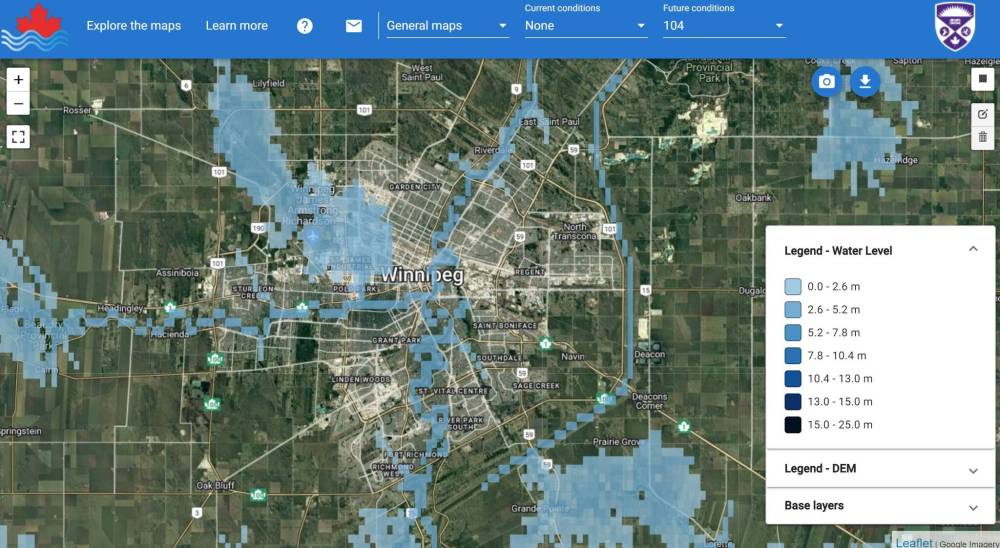

Simonovic has put together satellite maps that show where water will run with higher flood levels caused by climate change during the next four decades. They show what could happen in Winnipeg and southern Manitoba when the waters rise and why protection needs to be continually monitored and evaluated.

The worst-case scenario map is ominous. It shows a large body of water across much of northwest Winnipeg created by streams flowing into an already flood-swollen Assiniboine, which becomes a lake between Headingley and Portage la Prairie.

Another large lake begins southeast of Winnipeg at Grande Pointe and St. Adolphe and stretches across almost to Steinbach.

Thankfully, there is a caveat.

“The possibility is that the data do not account for all the existing protection infrastructure… we don’t have a crystal ball,” Simonovic says.

● ● ●

Curtis Claydon, a councillor in the Rural Municipality of Ritchot whose ward includes Ste. Agathe, says while people remember 1997’s destruction, many have forgiven the river and have chosen to embrace it.

A boat launch was recently constructed in town, allowing residents to get on the water, and also to attract visitors with fishing boats — and their dollars — to support local businesses.

“It has almost always been a ‘don’t touch’ attitude’ but now we have locals and others out fishing on it,” Claydon says. “The community has tried to make sure the Flood of ‘97 doesn’t identify us.

“You always know the river is right beside you. It is beautiful, but you have to be mindful of its power.”

Kristjanson knows all about the power of water, as he travels Lake Winnipeg on the hunt for pickerel. He was planning a celebratory reunion fish fry in southern Manitoba until it was put on hold by this year’s flood concerns.

“You always know the river is right beside you. It is beautiful, but you have to be mindful of its power.”– Curtis Claydon, councillor in the RM of Ritchot

He hopes a major flood never happens again, but his family is prepared to ready their boats again if there is one.

“I had people in our boat looking at their homes under water,” he says. “What people lost — they had left with nothing.”

Kristjanson also ferried “thousands of sandbags” to people trying to save their homes. It’s because of those connections made 25 years ago that he’s still hoping to get the fish fry off the ground this year.

“I’ve been to weddings down there,” he says. “People come up to Gimli and they buy fish from me. That’s why I want to have the fish fry.

“We met an awful lot of nice people.”

kevin.rollason@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @KevinRollason

Kevin Rollason is one of the more versatile reporters at the Winnipeg Free Press. Whether it is covering city hall, the law courts, or general reporting, Rollason can be counted on to not only answer the 5 Ws — Who, What, When, Where and Why — but to do it in an interesting and accessible way for readers.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.