Truth, in Black and white Sometimes subtle, often unintentional, the crippling power of individual and institutional discrimination based on nothing other than skin colour takes a mammoth toll on many who call Winnipeg home

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 03/07/2020 (2079 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

From the outset, the goal of this project was to highlight and amplify the voices, stories and lives of Winnipeg’s Black community.

We asked our contributors to write a reflection on one broad question: what is your experience of being Black in Winnipeg? We edited for style, but not for content.

What follows are the stories of Black Winnipeggers — in their own words — who share pain and pride, struggle and resilience. They tell stories of feeling like outsiders, of being pushed away from their communities. They counter the idea that discrimination and racism do not happen in Winnipeg. At the same time they offer stories of warm welcomes, of strong communities and of the beauty of self-discovery.

The Black experience, in Winnipeg and beyond, is not linear or singular. These stories present some of the range and breadth of that experience, while shedding light on the aspects that are shared and collective.

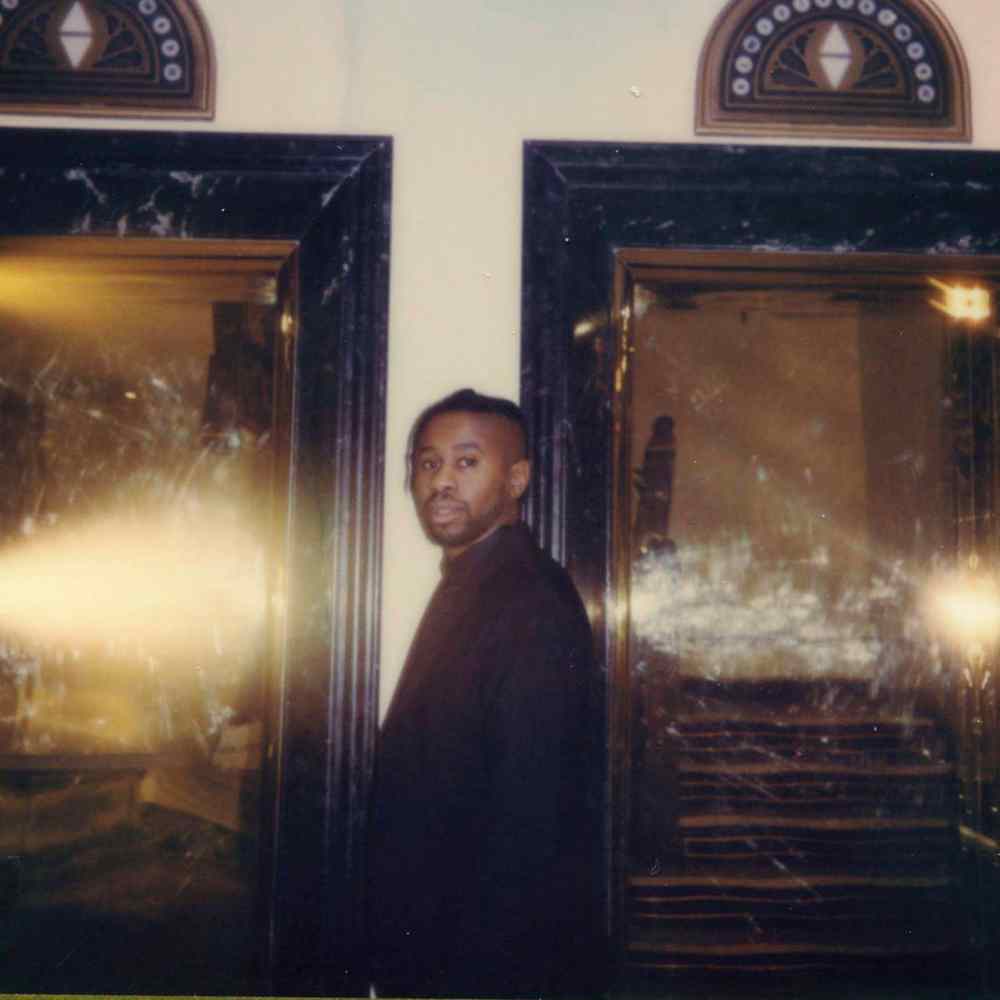

Portraits by Calvin Lee Joseph accompany each piece, putting faces to each unique perspective.

These stories are illuminating, honest and expressive. These stories issue a challenge to listen.

— Julia-Simone Rutgers

Luladei Abdi

social worker

As a Black Winnipegger and as an immigrant in Canada, I was always expected to feel thankful for living in the land of opportunities. I am indeed thankful for the life that I have here in Canada. Winnipeg’s diversity used to be such a calming idea for me.

Then I started working in places that are predominantly white and started seeing how being a Black person in Winnipeg is not as easy as I used to think. I started observing the racism experienced by our Indigenous communities.

As a Black person, your educational background is questioned, your stories as a Black person are questioned. Your experiences with racism are downplayed. Your ability to raise your children is questioned. But you cannot call it out, because you are conditioned to believe that racism does not happen here in Winnipeg, Canada. Not to Black people. I remember going to a pharmacy and a racist incident happened to me and my younger cousin. I remember complaining to the individual’s manager and being almost ridiculed. I remember writing about the incident to the local news station and being ignored because, again, racism to Black people does not happen in Winnipeg!

You are made to feel as though you are the problem, not the place where immigrants and refugees have been accepted with open arms. It is so subtle; it is scary to think about.

This is why I know that we, Black people and other minority groups, have to stick together. In the wake of what is happening in our neighbouring country, I know that I have to educate myself and share my knowledge with my non-Black friends in understanding the experiences of Black people in Winnipeg.

Kelly Bado

singer-songwriter

To be born black, for me, means being different and looking different, somehow despite the fact that we are all human. Having been raised in my African culture I could look up to beautiful African women around me — doing their hair, cornrows, braids. Loving their afros. Being proud of their heritage. But when I came to Canada it was different. All I saw on TV when it came to Africa was hunger and despair. I was wondering why they were only showing the worst and nothing about the beauty; painting a dark, sad and not attractive picture of Africa. It is not a perfect continent but there are a lot of positive things to discover. It saddened me and ever since I try to proudly represent my origins and show the beauty in us through my music.

James Murphy

community youth worker / former Winnipeg Blue Bombers all-star receiver

I was born and raised in the deep south in the U.S.A., Oct. 10, 1959. I remember segregation as a young boy — maybe six or seven years old. My mom would take my sister and I to the laundromat with her and there were two separate rooms. A sign hung on the wall in each room; one of them said “Whites Only,” the other one said “Coloureds Only.” It didn’t really make any difference to me at the time because I didn’t know any better: I lived in an all-Black neighbourhood, went to an all-Black school and all-Black church, the doctor was Black, mom and pop corner stores were Black-owned.

Volusia County (Florida) schools were among the last to integrate, which was enforced by court order in the 1969-70 school year. That second semester in fifth grade was a new beginning for me and all my classmates. It was a COVID-19 moment for me — nobody knew what to expect. While it was a time of uncertainty, I cannot remember any major incidents.

Two years later when I started playing football all my coaches were white, except when I played my first two years of baseball. From junior high until my professional career was over, all of my head coaches were white. I cannot recall any moment when I was treated unequally.

Living in Winnipeg for the last 30-plus years, I have not experienced any racism nor can remember any time where I can say I was discriminated against. Maybe it is because I had a great football career, which came with advantages. I have to say I have received more passes than discrimination, but that’s not to say I believe there is no injustice caused by racism to people of colour.

Boma Cookey-Gam

actress / singer / dancer / direct support worker

To be honest, as crazy as this may sound, I’ve never actually thought about what it means to be Black in Winnipeg — not because I’m ignorant, but because I’ve never had to.

I grew up in Nigeria and upon moving to Canada, I didn’t immediately notice anything different, except maybe a difference in culture. Everyone seemed nice and friendly — until they weren’t.

Being Black in Winnipeg has meant having people ask if I speak English (it’s my official language) back home, people refusing to take the only seat left on the bus beside me, visiting my brother in Saskatchewan and having boys drive by and yell the n-word at us, white people speaking in tones that suggest, “She may not understand us, so let’s dumb it down for her” and having white males try to mansplain what my hair is like.

Being Black in Winnipeg has also meant bouncing from one friend group to the other because I don’t fit in with my black counterparts — too white, they said. From being the only Black person in my white friend group to being the only Black person at work; having to try to fit in but not succeeding, so forming a community of immigrants because they’re not white, and maybe they understand what it means to not be white.

But most of all, being black in Winnipeg has led me to a place where I have found a community of different types of people — Black, white, Asian, Indigenous — who really just appreciate your culture and support and encourage you, embracing who you are. And that’s what it has become: it is now about finding who I am, not only as a black woman but as a person, in general. And that has been a very empowering journey. It is ultimately teaching me how to express myself and be who I am. To find my story and my voice. To learn and unlearn toxic and damaging behaviours that have shaped my identity, all while claiming my heritage and repping it to the max.

Anthony Sannie

hip hop artist/owner of Grape Experiential

The 47 is about my mother’s introduction to Transcona, Manitoba, Canada. I envisioned what her life could have looked like between 1971-1978. She was in her early teens during this time and she used to catch the 47 (The Kildare) bus regularly. Black people living in Canada have varied relationships with place. Sometimes these relationships are positive, but sometimes (Black, Indigenous, People of Colour) BIPOC struggle to fit into a world that is othering.

Dr. Lois Stewart-Archer

Hon. Consul of Jamaica in Winnipeg / Congress of Black Women of Manitoba past president

Being Black in Winnipeg requires resilience, confidence and self-love. To put this in perspective, one has to look at the history of being Black in Winnipeg. I recently completed a research project on behalf of the Congress of Black Women of Manitoba with funding from the Multiculturalism Secretariat of Manitoba in which I had the privilege to interview 10 Black educators who immigrated to Winnipeg and taught between 1960 and 1980. While for some the reception was initially frosty and their struggles numerous, they all gradually made friendships, created a support system and decided to stay and raise families. They managed their hardships with grace. A reassuring notion, this gave me greater perspective as this echoed my experience immigrating 10 years later — true resilience.

As Black persons in academia, the workplace or any predominantly white environment, we feel pressured to consistently function at our highest levels. We also may experience “impostor syndrome” or the constant internal battle in which we feel like we have to prove why we deserve to be in the spaces we occupy. This is a result of constantly disproving negative stereotypes and attempting to thrive within environments in which so few of us are welcomed.

I have found that I am at my best when I am content, confident and at peace with who I am. To me, self-love includes finding a community of like-minded individuals who help you to feel less “other.” I have been blessed to find strong Black community members through community organizations, church and cultural initiatives that place a high value upon our heritage.

I was proud to see thousands of Black Winnipeggers and allies stand in solidarity for the Justice 4 Black Lives protests. We have come such a long way, but there is still more work to be done.

Seid Oumer Ahmed

social justice advocate / former journalist

I was intrigued when I was asked to write about what it means to be Black in Winnipeg. For me, Black is a term that has been imposed on Africans as a derogatory label to erode African identity, to dismantle their humanity, and to boost a sense of white supremacy.

I came from Ethiopia, the birthplace of humankind, a diverse country packed full of history, a home to more than 80 different ethnic groups who live unique and fascinating lives with a sense of pride. Ethiopia is the only African nation that has never been colonized. The defeat of a European power by Ethiopian forces during the colonial era turned Ethiopia into a symbol of freedom for African nations and people of African origin globally.

Ethiopia welcomed Muslim refugees fleeing persecution over 1,400 years ago and at times with a Christian King who masterfully demonstrated religious tolerance and welcomed refugees. In the 13th century, we welcomed Beta Israel when the civil war broke out between the Jewish population and Christian population. During this time of increased Islamophobia, often linked to anti-immigration sentiment, we in the West can learn from the history of inclusion and welcoming that my home society of Ethiopian demonstrated many times over the years.

As a person of African origin, I’ve faced prejudice, racism and mistrust in many different circumstances, but in response, I always define my ethnic origin while I push back around the idea of defining race using skin colour. I also must say I have been treated with respect, dignity and love beyond words by my Canadian sisters and brothers.

The Western classification of race — Black, Asian, Hispanic, white, etc. — are a strange concept that exist only in the West: Whereas at the birthplace of Humankind race and colour are two different things. Colour is not associated with race. If you ask someone in a rural area, who protects a strong identity, “What is your race?” it would never cross their mind to say that they are Black or brown. Instead, they would say “I’m Gurage, Amhara, Tigrai, Afar, Oromo, etc., which are all their ethnic groups. Meanwhile, as Ethiopians, our “racial” classifications of foreigners are often based on national lines; for example, Italian, Chinese, American, Kenyan; not Asian or white. For this reason, I do not support another set of classifications, particularly a label like “Black” that aims to discredit my humanity! I don’t care if you are blue with purple hair — rather, it is your humanity that matters the most to me.

Individual racism is nothing but ignorance and stupidity. But what really bothers me is the systematic racism that persists in our schools, workplaces, immigration system, justice system, police departments, etc…. While there is no explicit policy that excludes people of African origin from to advancing to a senior position, there are underlying biases and foundational perspectives that are still carried out by white people who occupy the majority of positions with decision-making power.

To create change and to mend the inequality that exists in every institute, as well as in many people who hold both junior and executive-level positions, decision-makers must re-examine their own leadership views and actions. They should commit to looking inward, acknowledging personal and structural bias and pushing progress forward on inclusion to address the enduring legacy of racism and to undo the structural elements that have been sustained for so many years.

Sappfyre Mcleod

youth mentor, co-facilitator at Project Heal

Winnipeg has a long-standing tradition of normalizing the implicit biases that run rampant in the city. Thoughts on class, race and privilege go unchecked and unchallenged for so long that citizens abide by them as though they are fact.

The thing about being Black in Winnipeg is that you are likely to exist in an intersection of any of these points of class, race and privilege. As a Black person, people make assumptions about these intersections, projecting their biases on to you at an alarming rate, regardless of your own personal station, your wealth, education or income. Not understanding that your Black life has innate value outside the realm of any institution.

What happens in Winnipeg is that, socially, as you find out that we are human — and not the living embodiment of the construct that you’ve created — folks in the city will either distance themselves from a Black person, make shallower connections with said person (a very alienating practice) or find someone that is willing to live out their perception of what a “Black person” is.

This distancing that takes place is harmful because there is no room for non-Black people to challenge their biases and grow. Subsequently what happens is that the Black person is removed from the space or lessened when present — meaning their input or decision-making power holds less weight socially or corporately in a room with their non-Black counterparts.

These silent norms that exist within the city are toxic. It is a violent, systematic way of hindering the progress that Black folk can make in the city without ever having to feel implicit or responsible for the things happening around you.

The process, whether unintended or “well-intended,” as it may seem, does not negate it from being harmful because racism isn’t about feelings, or being a good person or intent — it’s about power.

In Winnipeg, people need to ask themselves what they are really doing to share the decision-making power, to create equitable resource distribution in ways that aren’t coded or needlessly laborious for Black people to access.

I believe Winnipeggers have the capacity to do so, and I need to see it.

Mungala Londe

youth programs manager / musician

The second time I was almost killed by cops happened Monday, April 20, 2015, around 11 a.m., before my noon yoga class. I was early for the class, and driving a little aimlessly around Confusion Corner before deciding I’d eat my breakfast in the parking lot of Burger King. As I was waiting to turn at the traffic lights, an older white guy pulled up beside me like he knew me and like he was very upset with me, personally. His red face looked hard through his window until the light turned green and he peeled off. I shrugged off the encounter and proceeded to turn into the parking lot. I took out my homemade muffins and my soy milk and turned the radio to CBC news.

The red-faced, white gentleman came screeching up beside my truck. This time he was yelling at me. I thought I was stepping out to scrap with some old random white guy, and then I spotted his gun. Two more SUVs pulled up in front of me, over the drive-thru lane, and more men in bulletproof vests were coming, yelling at me. I stepped out of my vehicle to see another two SUVs had flanked my truck from the rear. I was surrounded by an elite police squad. This wasn’t the first time the police had come at me with this kind of energy, so I was nervous, but not panicked. I’m a good dude, I was working a good job, and I was well known in the local music scene. I was supremely confused but prepared to answer any questions they had. One question, “Where do you work?” excited me; at the time, I was working for a specialized adolescent treatment centre, and I loved it. The problem was, when I’m excited I talk with my hands, so when I moved to answer, they immediately screamed at me and trained their guns to my face. I remember crushing the muffin in my hand, and it falling to the ground while I held my hands above my head. I forced myself to answer the question as calmly as possible, sounding like I knew I’d been “that close” to dying.

I tried to ask questions, but one of them was extra rude, like “only answer when we ask you to,” and “only look where we tell you.” I thought about how this wasn’t the first time I’d almost been killed by cops, about how I felt ready to sue them. But I’m a fair guy. I felt like I had a responsibility to see their perspective. I wasn’t dead, some of these officers looked young, and they didn’t all look like assholes. I knew something wild must have happened for this elite unit to nearly kill me. Another man told me to watch the news that night for answers. I asked if Winnipeg was really “crazy like that,” and he told me I wouldn’t believe some of the stuff he’d seen. So I stood there, turning in whichever direction they asked for about 30 minutes — long enough (that) I actually asked them if I had time to make it to my yoga class or if I should forget about it. They returned my things to me, and I promptly drove off to have a really bad yoga class. Shaking on the mat, my focus just wasn’t there. I was stuck in that parking lot, reliving the scene.

I checked the news every day for a month before there was any mention of why this happened to me: a small blurb in the Sun, about an unsolved murder in a back lane somewhere in the Elmwood area. Suspect still at large.

Every time I think back, I consider the fact that not all those cops were bad apples. But nothing upsets me more than knowing they never had a suspect. The simple reason they nearly killed me is because one man profiled me as threatening. Me, eating my muffin and sippin’ my soy milk, CBC radio playing in the background.

About the photographer:

I’m a Caribbean-Canadian. I was born and live in Winnipeg by way of my British-born parents. One goal I’ve actualized is making a living being creative. Photography is one of my callings that I’ve turned into a profession, although admittedly, it’s one of three. My story with photography isn’t interesting; I didn’t grow up with a camera in my hands. The truth is, I picked up photography later in life as a form of expression for myself and my subjects. I’m drawn to assignments that include a subject. No matter the job, be it portraits, events, lifestyle or beauty, my work illustrates the story of my subject. Offering a subject, a platform where they are seen and represented is the foundation of my practice. This body of work you are reading underscores that same foundation. Thank you for interacting with these beautiful stories.

— Calvin Lee Joseph

History

Updated on Friday, July 3, 2020 9:32 PM CDT: Fixes formatting of poem.

Updated on Friday, July 3, 2020 10:23 PM CDT: updates poem edits

Updated on Friday, July 3, 2020 10:40 PM CDT: Replaces text of poem with pdf at reporter's request.