An apology for marginalizing people of colour; and a promise to atone for our past

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 03/07/2020 (1987 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The St. James of my childhood was a largely monochromatic world.

Most of our neighbours were Caucasian, or more simply, white. So were my classmates. The same could be said for the subscribers on my Winnipeg Free Press paper route.

The area’s white member of Parliament, Dan McKenzie, made headlines by defending apartheid after a visit to South Africa in 1982 and suggesting Black people made natural car mechanics. Despite the controversy his remarks created, he was re-elected in 1984.

Six years later, I walked for the first time into the newsroom of the Free Press, a local institution which, like so many others in the city at the time, was also very white.

Since then, much has changed in my old neighbourhood, in our city and at this newspaper. Many of those changes have been for the better, but they have not been enough. The world has never been monochromatic, even if governments, institutions and societies act like it is. And reflecting on these places and processes that have all too often been blind to the realities of race goes a long way toward beginning to understand what’s been wrong for far too long.

Amid the first wave of COVID-19, at a time when social distancing is key to wrestling a global pandemic to the ground, we have come face-to-face with a wave of racial reckoning.

The haunting image of a white police officer’s knee pressing down with deadly force upon the neck of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, sparked a worldwide conversation about race, racism and injustice. These are difficult but necessary conversations that need to happen around the world — and are taking place in our newsroom as part of an overdue reckoning within the journalism profession about its role, responsibilities and redress.

Those discussions and debates at the Free Press have us taking a hard look in the mirror — and the rear-view mirror — to consider the truths about the privileged position we hold in this city and province, and where we have succeeded and failed in our duty to this community.

The power of the press is one that can right wrongs by shining a light. And to the extent that fundamental fault lines remain in our community based on the colour of one’s skin — where people of colour are not afforded the same opportunities, the same rights, the same advantages — we must concede that it’s partly the fault of this newspaper.

The historical record shows that one of our early owners, Clifford Sifton, was a man whose plan to open up the Canadian West as the country’s immigration minister was rooted in racism. His preference, in attracting settlers to farm the land that was the traditional homeland of Indigenous peoples, including the Métis, were those of British stock and from northern Europe. Black people, Jews and people from Asia were not part of his plan for Western Canada.

Legendary Free Press editor John Dafoe, who oversaw the paper from 1901 to his death in 1944, suggested in the wake of the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike that it was time “to clean the aliens out of this community and ship them back to their happy homes in Europe which vomited them forth a decade ago.”

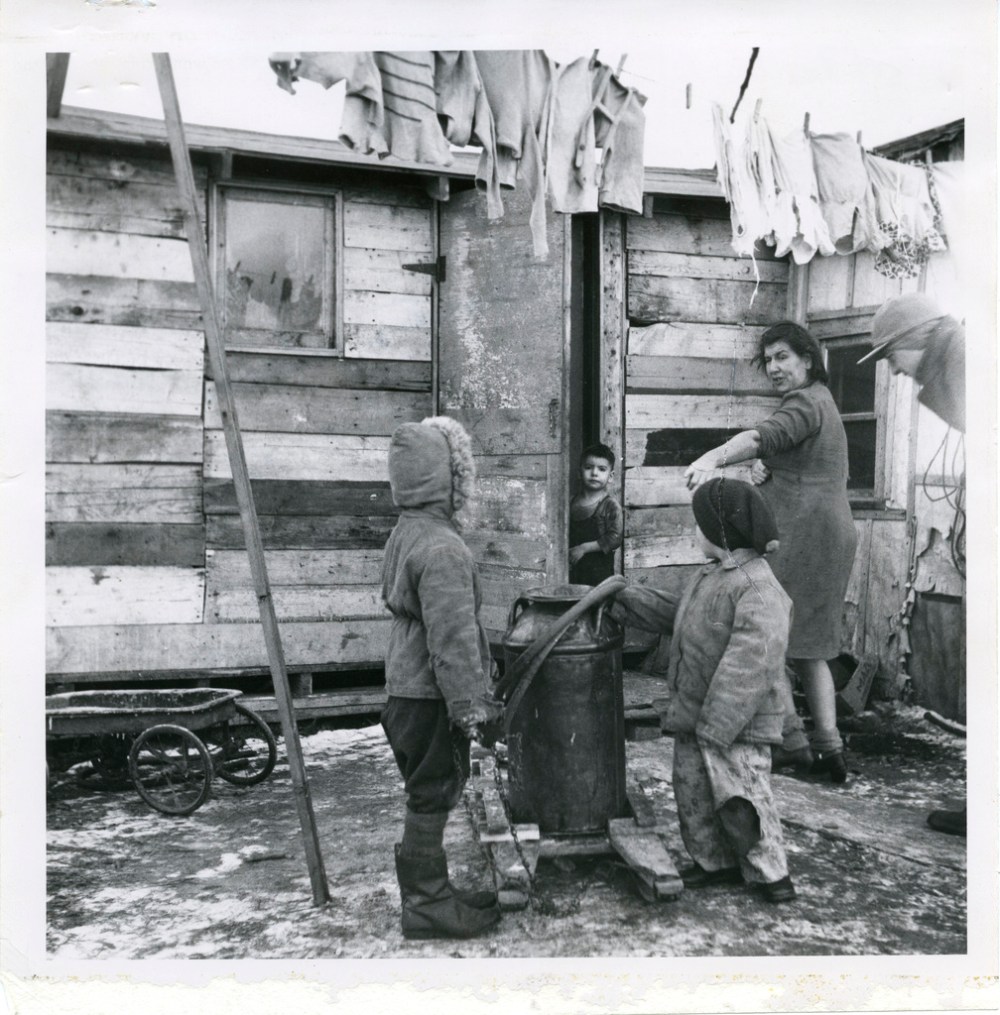

The one-sided demonization of Métis citizens of Rooster Town in the 1950s took place on our pages, allowing city policymakers to gain political momentum to remove and displace the community. When the newspaper wasn’t echoing societal opinions about race, it was silent while beaches, golf courses and private clubs banned Jews and people of colour.

During my time at the Free Press, the deaths of Helen Betty Osborne, J.J. Harper, Brian Sinclair and Tina Fontaine have all reminded us that race is a definitive factor in the violence and injustice in our city and province. But what about the other people of colour who were victims of injustice at the hands of police, the courts, our hospitals, schools and the child-welfare system? Their names are not part of the record we have built since 1872 because we failed to dig deeper to get at their stories.

The stories a newsroom pursues are often reflective of those who work in it. That means the stories we publish embody the views, experiences, interests, concerns and fears of reporters and editors. So when our newsroom collectively looks in the mirror, the faces staring back at us should reflect our broader community.

Like too many newsrooms, ours is not as diverse as it should be and those hiring decisions have had real-life effects measured in decades.

We are committed to changing this trajectory. In May 2019, the Free Press established a goal to have a newsroom far more reflective of the community we serve by the time we celebrate our 150th anniversary in 2022. While the past year has not been an easy one for our industry, we have still found a way to make progress toward that goal. At a time when newspapers everywhere are shedding jobs, the Free Press has added four people of colour in full-time reporting positions.

These new members of the Free Press team are integral in enabling us to broaden our perspective and strengthen our journalism by bringing insight, understanding, lived experience and sensitivity. They also help us build upon a foundation that saw the Free Press become the first major Canadian daily newspaper to issue a treaty land acknowledgment and hire an Indigenous city columnist.

While changing the face of our newsroom is a long-term project, the demands of the conversation echoing from the street to the corridors of power are long overdue.

That’s why we’ve launched a major examination of race and racism in our province — a newsroom-wide initiative that will generate stories over the course of the next several months. The first of that special project debuts today as our 49.8 cover story.

That’s also why we are closing down our online commenting section as of July 14. While much of the conversation involving our readers is healthy, we all too frequently have to shut down comments on certain stories that can be magnets for racist commentary. We want no part of spreading such opinions and will instead introduce new ways to engage with readers and to share their voices.

That’s why we recently changed our style guide to uppercase “Black” when describing a person’s race, culture or community. The move follows a similar one earlier to upper-case Indigenous. These moves, which might seem simple, speak to a more fundamental effort on our part to be respectful and sensitive to the communities we serve. We will continue to listen in a bid to further strengthen our journalism.

That’s why on behalf of the Free Press, I am apologizing for the times when our coverage has fallen short, for being blind to those marginalized by the colour of their skin, and yes, for a history that shows we have, at times, been part of the problem, not the solution.

We can do better. We will be better because our readers, our city and our province deserve the best from the Free Press.

Paul Samyn is the editor of the Free Press.

paul.samyn@freepress.mb.ca

Paul Samyn has been part of the Free Press newsroom for more than a quarter century, working his way up after starting as a rookie reporter in 1988.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, July 3, 2020 7:34 PM CDT: Fixes typo.

Updated on Friday, July 3, 2020 8:25 PM CDT: Removes incorrect photo

Updated on Saturday, July 4, 2020 10:54 AM CDT: This piece has been updated to clarify that the Métis are included among Indigenous peoples.

Updated on Saturday, July 4, 2020 5:22 PM CDT: Adds links to editorials regarding the Winnipeg Free Press' newsroom diversity and the paper becoming the first major Canadian daily newspaper to issue a treaty land acknowledgment.