Emerson at war Border community's farmers, horses pulled their weight in the Second World War, dragging U.S.-made fighter planes destined for the Allied effort into Canada

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 08/11/2019 (2227 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

“In the early days of the present war, a Neutrality Act prohibited American manufacturers from delivering planes to belligerents on foreign soil. Sympathetic to Great Britain and her allies, but legal to the last, their pilots were ordered to fly their ships as close as possible to the Canadian border. Democratic ingenuity — and a stout rope — did the rest.”

— Narrator speaking in A Yank in the RAF (1941)

EMERSON — With the mountains of Manitoba in the background, a Harvard trainer aircraft is hooked to a heavy rope and pulled north by a Maple Leaf Garage tow truck waiting across the Canada-United States border in early 1940.

More single-engine planes are lined up behind that one.

Mountains? In the distance at Emerson and Pembina? Manitoba and North Dakota?

Well…

It was a bit of Hollywood fakery to film the 1941 Darryl Zanuck-produced musical A Yank in the RAF, starring Tyrone Power and Betty Grable.

https://youtu.be/4Cpa8RMtrGI

But while the movie scene was shot somewhere in rural California, the subject matter — without the mountains — was real.

Most Manitobans likely aren’t aware that the familiar border crossing area had a small, but important, role in the Allied forces’ Second World War success.

The hidden-in-plain-sight “smuggling” operation took place on two farm fields about a kilometre west of the current Highway 75/Interstate 29 crossing.

Black-and-white photos captured teams of horses, guided by farmers, pulling the airplanes into Canada, bound for the war effort.

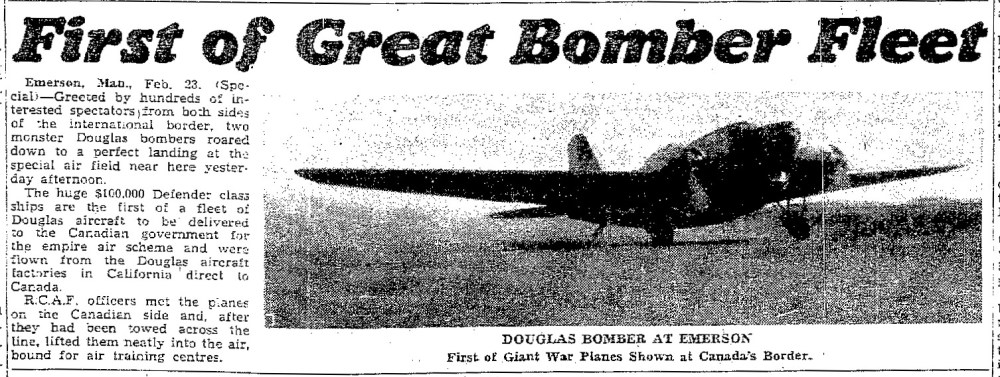

A Feb. 23, 1940, Free Press story with a photo reports, “Two monster Douglas bombers roared down to a perfect landing at the special air field” before hundreds of people on either side of the border. The article went on to report the $100,000 Defender-class planes were the first of a fleet of Douglas aircraft on their way to Canada.

● ● ●

Almost eight decades later, Robert Milne is standing where those planes landed. Milne, a farmer, owns the quarter-section of land used for the operation on the Canadian side.

He took a Free Press reporter and photographer to the site, driving down a muddy trail to what he called a “road” — little more than two ruts through grass and weeds running east and west just on this side of the border.

The only indication of the international dividing line are the stubby aluminum markers with “Canada” on one side, the occasional pole with attached surveillance equipment and the low-flying helicopter that suddenly appears, hovering over Milne’s pickup to see what the trio is doing there with nary a tractor or combine in sight.

But there’s nothing commemorating what happened here in in 1940.

“My uncle always called it the Airport Quarter,” Milne said.

“I now wish I had asked him more about it. About all I know is they towed planes across here. It’s kind of cool, though. And they used horses.

“Horses were still pretty common back in 1940; I remember horses and I wasn’t born until 1954.”

● ● ●

In order to understand what happened here and why, we have to go back a few decades earlier to the days following the end of the First World War.

In the immediate aftermath of the Great War, a significant number of Americans — politicians and citizens — began advocating for isolationalism and staying out of other nations’ conflicts. Throughout the 1930s, as European countries fought and fell to Adolf Hitler’s Nazi machine, the United States Congress passed various pieces of neutrality legislation preventing political decision-making that would result in American military intervention.

The problem faced by then-president Franklin Roosevelt was that the legislation labelled both aggressor nations and the countries that were invaded as “belligerents,” preventing the United States from offering other support to help Britain and France against Hitler’s forces.

“The United States could not sell to a nation in conflict or at war,” said Bill Zuk, a local aviation historian and author.

“Even though England had bought the planes before the war, it was now how to get them over.”

Besides Emerson, the Royal Canadian Air Force also imported American aircraft at Coutts, Alta., and Woodstock, N.B.

Jerry Vernon, who served as a reserve officer with the RCAF before retiring as a major, researched and wrote an article about the transfers for the RCAF Journal in 2016, after discovering a file in the Public Archives of Canada called Delivery of Aircraft from U.S.A. under U.S. Neutrality Law, 1939-41.

Vernon said up until 1939, American aviation manufacturers were having no problems ferrying planes to Canada, but then the American Neutrality Act was amended by Congress.

He said that’s when a new scheme was devised to get planes across the border.

“There was a lot of ‘nudge, nudge, wink, wink,’ going on with president Roosevelt to circumvent the Neutrality Act while still living up to the legalities of it until it could be amended.”

Vernon found a letter in the file, sent by Flying Officer Alf Watts to the commanding officer of Western Air Command on Nov. 13, 1939, just two months after Canada declared war on Germany, which discusses who had to fly the Harvard planes and how they would now have to be delivered from the North American Aviation factory in California to Canada in order not to breach the Neutrality Act.

Watts admitted in the letter he and an American customs broker from Sweetgrass, Mont., came up with the scheme together while sitting in the broker’s car.

“No American pilot can fly a machine across the border into the country of a belligerent nation,” the letter says. “The machine, therefore, has to be shipped or towed across the border at the point of delivery, and from that time on, it is in the hands of the receiver, and the Americans will have nothing further to do with it.”

The letter goes on to say that the plane also must be delivered to a Canadian who is not a member of the fighting forces “on the American side of the border, who accepts it, rolls it across the border, and then turns it over to whomever he pleases.

“These two points sound rather technicalities (sic), but apparently they will have to be lived up to to the letter if the machines are coming across.”

Watts writes, “The following plan is respectfully suggested.”

“That two fields be found, lying side by side on each side of the border… the machine will be landed by (an American pilot) on his side, checked and cleared by a Canadian broker, the release then being obtained from the American customs, and the machine then being brought over to Canada where I would immediately take it off and fly it.”

At first, two fields, one in Sweetgrass and the other in Coutts, were used, but there were concerns the site wouldn’t be suitable for larger aircraft and would be more difficult to clear of snow. Flatter fields were required.

In a handwritten note, in response to a suggestion a month later that another “reasonable good landing field” be found along the international border, George Croil, Chief of Air Staff of the RCAF, said “I suggest you investigate the possibility of the landing grounds of Pembina, Minnesota (sic) as an alternative to… Montana.”

● ● ●

Jim Moris and his brother Frank own the relatively small — by North Dakota standards — 47 acres of land originally purchased for the landing site. Tim Wilwand owns the fields around it and the main access road to the site.

“I know the planes landed there and they’d pull them across with a team of horses, but there’s no sign or anything saying this on the land,” Jim Moris said.

“It’s just a regular farm field and it has been growing crops for years. It would be neat if there was a marker put out there.”

“I think it’s awesome what they did,” Wilwand says. “I was watching a show that talked about it and my dad said, “I have a picture of it.” He said I should have it because it is from up north of your farm.

“It now hangs in my office.”

Vernon found a memo from January 1940, showing it cost $4,500 to purchase the quarter-acre of land needed on the Canadian side and $4,200 to buy the same area of land on the American side. Costs for improvements and maintenance on both properties was $2,000 so, with legal fees, it cost a total of $10,727.85 for the entire transaction.

Vernon also found a letter in the file written on March 4, 1940, by Milne’s uncle, Alex Milne Jr., to the RCAF, saying “at present the planes are being towed by a team of horses, but they are not handling them very well.

“As caretaker of the International Airport, I should like to offer the use of my tractor for the purpose… it seems to me that it would be better to use a tractor rather than horses at any rate, but the one team has scarcely the power to move the big planes and I’d rather not have more horses trampling the runways.” The RCAF didn’t agree and the horses continued in their role.

● ● ●

Once over the border, the planes were fuelled up for the short flight to Winnipeg before heading off to battle or to instruct pilots in the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan.

“It is fascinating that, to not be seen as helping out, (the Americans) find this way of helping before they entered the war,” says Stephen Hayter, executive director of the Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum in Brandon.

“It was something very valuable to the Plan. We were trying to find planes. These planes would have been flown anywhere in Canada — wherever the need was. Some would be here for training, while some would have gone overseas.”

The transfers began during the Prairie winter; in early January, a letter from Lockheed, one of the manufacturers, informed the pilots involved that “the purchase of overshoes, heavy gloves and winter pull-down caps are chargeable on your expense account”.

But the letter adds “these articles must be turned in at the factory on completion of this mission” and no dress overcoats were allowed.

Ted Barris, who wrote the book Behind the Glory, about the Commonwealth Air Training Plan during the Second World War, agreed the scheme was a clever means to an end.

“They needed as many trainer aircraft as possible and most were being built in northern California,” Barris said.

“(A Yank in the RAF) was Hollywood playing loose with facts, but the aircraft part was true. They flew the Harvards here and then the farmers pulled them across the border — literally. FDR couldn’t be seen to be aiding another country.”

Wayne Arseny, vice-president of the Crow Wing Trail — which makes up part of the Trans Canada Trail from Emerson to the Floodway gates — and former mayor of Emerson, said at the time dozens of local residents would have watched the goings-on.

“I know it was all hush-hush back then, but to see a World War Two plane and see locals pulling it would have been quite a sight,” Arseny said. “Anyone farming in that area would have seen action. Planes in the area were uncommon back then.

“But the 49th parallel is still a very interesting place for the community. When a bus comes to town I take them to the road where the migrants cross. When they see the Trans Canada trail sign they know they’re in Emerson.”

It may be a bit of irony that longtime Pembina resident and farmer Bert Warner left the area to find work during the Depression and ended up in California. Working at Lockheed.

“It was hard to find a good job during the Depression,” said Warner, 96, who worked for the aircraft manufacturer until he enlisted in the navy.

“When I came back from the war, nobody really talked about the planes here. They never really talked about it. And, shortly after, we were at war with Germany.

“But it was a part of the time.”

Trish Short Lewis, who grew up in St. Vincent, a community across the Red River from Pembina, and now writes an extensive online history blog about the area and as far as Winnipeg, said she first learned about the planes from her late mother.

“Even though they were trying to be discreet, they weren’t hiding it. It was published in newspapers. (Howard) Hughes was talking about it.

“I guess they figured if they were above board, why hide it?”

It’s not clear exactly how many planes were delivered at the Pembina-Emerson crossing.

Vernon said there were as many as 16 Douglas Digbys and 18 Lockheed Hudsons. But he also found information that “North American (Aviation) and Douglas (Aircraft Company) had been using (Emerson) continually.

“North American were taking three to five aircraft per week via Pembina… finally, at least eight used airliners and twins flew in via Emerson out of 26 such aircraft bought.”

Vernon said his research has found at least one of the planes towed across the border at Emerson still exists. He said the Boeing 247D is now housed at the Canadian Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa.

The cross-border scheme effectively ended as quickly as it began when the Americans decided by late-summer 1940 they would now permit having both American and Allied crews aboard the planes and would transfer ownership and control while in the air, allowing them to land at Canadian airports.

And when Japanese forces attacked Pearl Harbour on Dec. 7, 1941 and the United States declared war, there was no longer any need for subterfuge.

● ● ●

Hetty Walker, a Pembina County commissioner and former Pembina mayor, said she didn’t ask too many questions when her late husband told her the story of the planes being pulled into Canada, but she pointed to it as an example of the enduring relationship between the two countries.

“It just shows the friendship… and that’s still there today,” she said.

kevin.rollason@freepress.mb.ca

Kevin Rollason is one of the more versatile reporters at the Winnipeg Free Press. Whether it is covering city hall, the law courts, or general reporting, Rollason can be counted on to not only answer the 5 Ws — Who, What, When, Where and Why — but to do it in an interesting and accessible way for readers.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.