Debt of gratitude

Manitobans owe much to the brave souls who died in defence of freedom

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 09/11/2019 (2230 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

With only two sleeps left until Remembrance Day, this seems like the perfect time to review a little poppy protocol.

“Thanks to the millions of Canadians who wear the legion’s lapel poppy each November, the little red flower has never died, and the memories of those who fell in battle remain strong,” the Royal Canadian Legion says on its website.

We all know that the bright-red flower has been our official symbol of reverence and remembrance since 1921, but you may not know there are rules for the “appropriate” and “respectful” wearing of the pin.

“The poppy should be worn with respect on the left side, over the heart,” the legion advises. “The legion’s lapel poppy is a sacred symbol of remembrance and should not be affixed with any pin that obstructs the poppy. Also available through some branches is the legion’s reusable black centre poppy pin to affix your lapel poppy.”

The lapel poppy should be worn from the last Friday in October until Nov. 11, according to the legion. It should be removed at the end of the day on Nov. 11 and “stored appropriately” or “disposed of respectfully.”

Nearly 20 million poppies were distributed in Canada in 2017, raising more than $16 million in donations for initiatives to support veterans.

But poppy protocol isn’t the only thing to keep in mind, as we see from today’s respectful list of Five Stories of Courage and Reverence that Manitobans Must Never Forget:

5) A story to remember: No Stone Left Alone

A time to reflect: Last Monday, with the help of local students, Brandon Municipal Cemetery was made to resemble the scene described in the famous Canadian war poem In Flanders Fields. According to the Brandon Sun, hundreds of students from École Harrison, St. Augustine School, Valleyview Centennial School and Riverheights School were on hand for the city’s sixth No Stone Left Alone remembrance ceremony.

It was just one of dozens of similar ceremonies taking place throughout Canada in the run-up to Remembrance Day as part of an annual tradition designed to ensure those who have served in Canada’s military are not forgotten. Maureen Bianchini-Purvis, whose parents served for Canada in the Second World War, started the No Stone Left Alone movement eight years ago. The first ceremony was held at Edmonton’s Beechmount cemetery. Since then, the tradition has expanded beyond anything those behind the first ceremony thought possible.

The ultimate goal is to have a student place a poppy on the headstone of every Canadian who has served in the military. For the past three years, the event has reached an international level, with No Stone Left Alone ceremonies held in Krakow, Poland. This year, The No Stone Left Alone Memorial Foundation is holding more than 100 ceremonies in more than 68 Canadian communities. Last year, more than 9,000 students visited 105 cemeteries and honoured nearly 60,000 veterans across the country. In Brandon, students and dignitaries surrounded the cenotaph as various people gave speeches, recited poems, sang songs and laid wreaths. Organizer Ryan Lawson, a local funeral director who brought No Stone Left Alone to Brandon, told the Sun the first school to participate was École Harrison, and it has expanded from there.

“Turned out we were the first school east of the Alberta border to put on a ceremony, and now it runs across the country,” Lawson said. In Manitoba, ceremonies were also held in Winnipeg, Portage la Prairie, Souris and Boissevain.

4) A story to remember: A Silver Cross mother

A time to reflect: Last Remembrance Day, a Winnipeg mother who fought for her son to receive full military honours after his suicide laid a wreath at the base of the National War Memorial on behalf of all military mothers who have lost a child to war.

Anita Cenerini was the 2018 National Silver Cross mother, an honour given by the Royal Canadian Legion. It marked the first time the legion had chosen a mother who lost a child to suicide for the yearlong designation. Her son, Pte. Thomas Welch, served in Afghanistan in 2003. The 22-year-old ended his life on May 8, 2004, at the army base in Petawawa, Ont. He was the first Canadian soldier to take his own life upon returning from Afghanistan, according to an investigation by the Globe and Mail. At the time, there were next to no treatment services for post-traumatic stress disorder, a mental-health issue now recognized as a devastating and invisible war injury.

“I knew his death was attributable to his service in Afghanistan. And I relied on that, that the truth would be recognized one day… as a soldier who died in service to his country,” Cenerini told the Free Press after the honour was announced. The grieving mother attributed some of her son’s suffering to survivor’s guilt. “I need to have him honoured as he deserved to be honoured, as a mother who had an incredible relationship with her son and saw the deterioration of his psychological well-being during his deployment,” Cenerini said at the time. The military initially determined his death was unrelated to his service. It gave Welch a military funeral, but he was not awarded the Memorial Cross, which is given to families after soldiers die in active service. His name was omitted from the Book of Remembrance, which honours Canada’s war dead.

Welch’s family members received his Memorial Cross in November 2017. After laying the wreath last year, Cenerini told the Free Press: “My vision, as a representative of all Silver Cross Mothers across Canada, is to bring awareness of the invisible sufferings of our soldiers and our veterans — which is what took Thomas’s life.”

3) A story to remember: Missing for nearly 90 years

A time to reflect: The recovery began when a teenager with a keen interest in the First World War started digging after spotting cartridges on the ground near his home in the French town of Hallu. Thanks to his keen eyes, in 2006 and 2007, the bodies of eight soldiers from a Winnipeg battalion were recovered after lying buried in the yard for nearly 90 years.

In May 2015, according to a story by Free Press reporter Mia Rabson, the Winnipeg soldiers, five of them now identified, were finally given a proper burial with full military honours in a British war cemetery in Caix, France. “Today, we lay to rest eight Canadian heroes, whose ultimate sacrifice for this country has great meaning irrespective of the time that has passed,” Lt.-Gen. Marquis Hainse, commander of the Canadian Army, said in a statement. The remains were identified as Canadians by the Canadian Armed Forces Casualty Identification Program.

The soldiers were all from the 78th Battalion in Winnipeg, known as the Winnipeg Grenadiers. DNA from relatives helped identify four of the soldiers and their names were released last September, the Free Press reported. The fifth, Pte. Sidney Halliday, was identified after his family helped the military connect a locket found with his remains to his fiancée in Manitoba. Halliday was 22 when he died. Lance Sgt. John Oscar Lindell was the eldest of the five soldiers identified; he was 33 when he died. Lt. Clifford Neelands was a real estate agent with a home on Dorchester Avenue in Winnipeg. He was 26 when he died. Pte. William Simms was a farmer in Russell, Man., and was 24 when he was killed in the battle. Pte. Lachlan McKinnon was 29 at the time of his death. He was the only one of the five who was married, having wed in Scotland during a leave from the front lines.

Along with about 100,000 other Canadian soldiers, the Grenadiers advanced on the Germans in the Somme region, north of Paris, in August 1918. “For the first time in almost a century, their names mark their gravesites. The graves of the three soldiers who haven’t been identified are marked ‘Known Unto God,’” the Free Press noted.

2) A story to remember: The Legion of Honour

A time to reflect: For Jim Magill, making it home alive was nothing short of a miracle. But getting a medal about 74 years later was nice, too. Last year, the 95-year-old Winnipeg veteran, surrounded by family, friends and an assortment of dignitaries, was named to the rank of Knight of the National Order of the Legion of Honour by the French government for his role in helping liberate France from Germany during the Second World War.

The Legion of Honour was first created by French military leader Napoléon Bonaparte in 1802, and it’s possible Magill could be the final Canadian soldier to receive it. “Sadly I think Mr. Jim Magill will be the last one here in Manitoba to receive this prestigious award — if not (the last) in Canada,” Bruno Burnichon, France’s honorary consul in Winnipeg, told the CBC at the time. Burnichon said the distinction is only given out to foreign soldiers who were in, near or flying over Normandy, France, on D-Day — June 6, 1944.

Magill was just 19 when he joined the Royal Canadian Air Force, shipped out to France and fought in the Second World War. He was the bomb-aimer on a flight crew of seven. After being honoured in 2018, Magill sat down with the Free Press’s David Sanderson to reflect on how lucky he was to make it home. “There was one night we were flying home from a mission, home being a little village outside Selby, North Yorkshire,” Magill said. “In error, we flew directly over Kiel, which was the headquarters of the German navy, including their U-boat division. Those guys took violent exception to anyone who went near their airspace and let me tell you, they hammered away at us, but good.” It wasn’t until they were over the North Sea, safely out of harm’s way, when they realized one of their gas tanks had been punctured and had lost all its contents.

The pilot radioed a master controller located on the eastern seaboard of England to explain the situation. “Listen to this: the very second we got to the end of the runway, our engine sputtered and died. That’s how bloody close we were to ending up in the drink,” he recalled.

1) A story to remember: The Angel of Misericordia

A time to reflect: It is impossible to share all the heroic stories of Winnipeggers during wartime, but this is one that everyone in the city should know. It may come as a surprise to learn the only nurse killed by enemy action during the Second World War started her career right here.

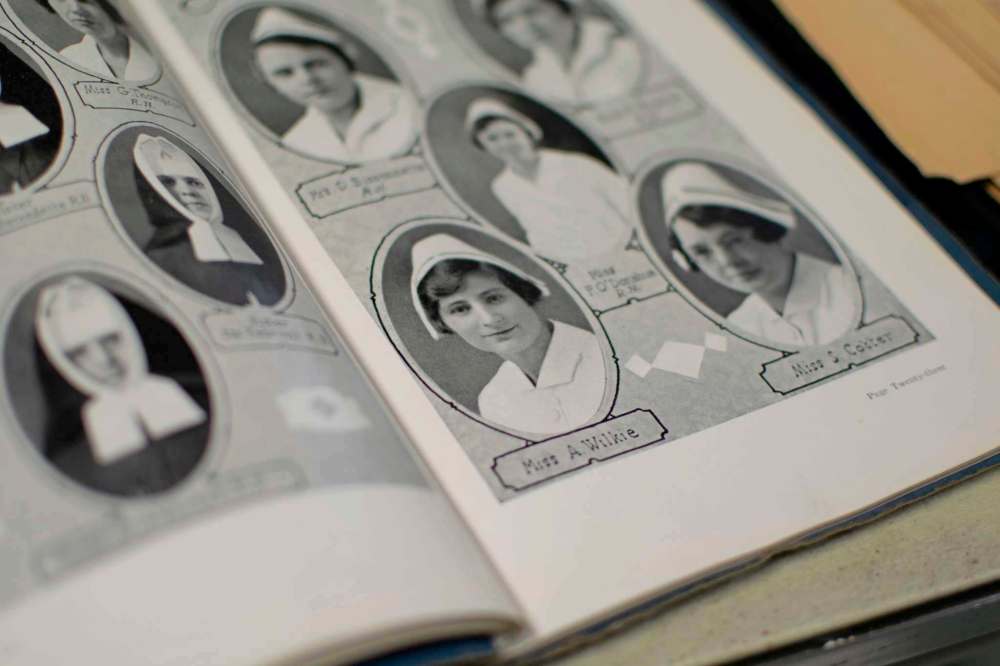

In 2018, the Misericordia Heritage Collection shared the remarkable story of Agnes Wilkie with journalists, including the Free Press’s Eva Wasney. Originally from Carman, Wilkie moved to Winnipeg in 1924 to attend Misericordia’s School of Nursing at the age of 21. Upon graduation, she worked in Misericordia’s operating room before volunteering to serve with the Royal Canadian Navy as a nursing sister in 1942.

As the Free Press reported, Wilkie was stationed at the naval hospital in St. John’s, N.L., and was returning from shore leave on Oct. 13, 1942, when the ship she was on was destroyed by a torpedo from a German U-boat. She survived the initial blast and later died from hypothermia, but not before having a profound effect on the other survivors. “Her story is one of courage and fortitude and just commitment to other people and I think we should celebrate it,” Dr. Barbara Paterson, chairwoman of the Misericordia Heritage Collection’s policy and planning committee, told Wasney. The S.S. Caribou, a ferry, was carrying 191 passengers and a crew of 46 when it was struck at 3 a.m. on Oct. 13. Wilkie was travelling with friend and colleague Margaret Brooke and had the forethought to get the life-jackets stored in their cabin.

“Margaret later said that saved their lives,” Paterson said. “They opened the cabin door and fell right into the sea because the boat was gone.” The pair swam to an overturned lifeboat. “The water was absolutely freezing and what Agnes and Margaret did is they calmed the people on the lifeboat,” Paterson said. “They sang hymns, they prayed and there are newspaper accounts of people saying that they wouldn’t have survived without them.”

Tragically, Wilkie succumbed to hypothermia. Wilkie was just 38 when she died — becoming the only woman serving in the Royal Canadian Navy killed by enemy action during the Second World War.

doug.speirs@freepress.mb.ca

Doug has held almost every job at the newspaper — reporter, city editor, night editor, tour guide, hand model — and his colleagues are confident he’ll eventually find something he is good at.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.