Document from 2007 has guided Manitoba Education pandemic response

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/05/2022 (1400 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

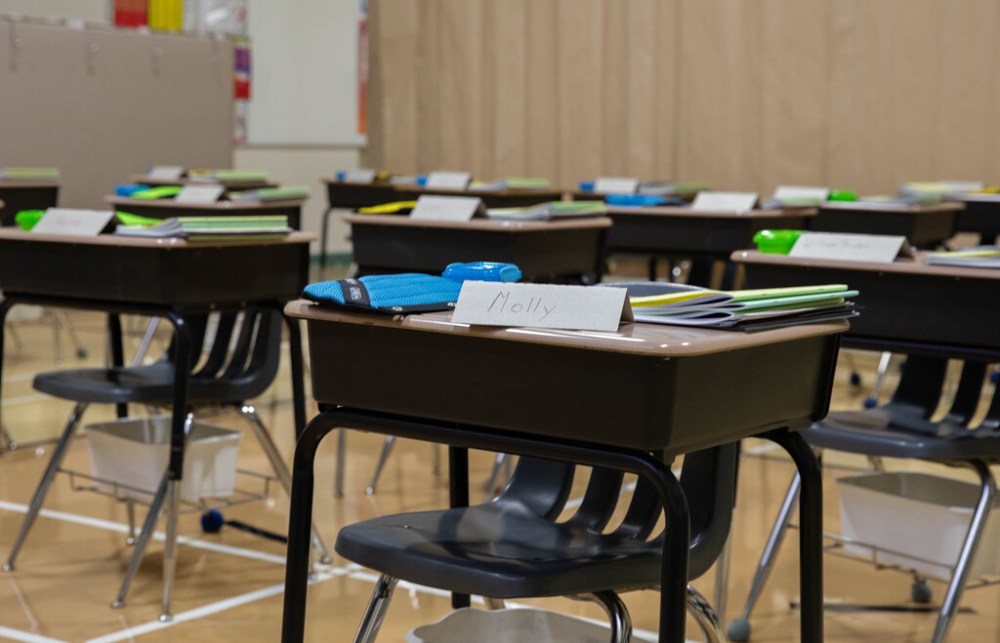

Saturday classes and “vacation school” are listed as options to make up for lost instruction time in the emergency preparedness plan that has guided Manitoba’s COVID-19 response to K-12 education.

In March 2020, Manitoba Education staffers circulated a 2007 document outlining pandemic guidelines for schools.

A physical copy of the plan, recently obtained by the Free Press, sheds light on the advice leaders have both acted upon and dismissed in managing operations over the last two years.

The 48-page document touts the importance of proactive continuity planning — which Manitoba’s auditor general recently concluded has been lacking in the education sector — and offers preparation tips for a global health crisis and subsequent recovery period.

Issues ranging from service interruption to staff absenteeism are discussed in-depth in the booklet.

“If we can’t staff during the weekdays, good luck staffing Saturdays,” said Brian O’Leary, superintendent of Winnipeg’s Seven Oaks School Division.

While noting his division has expanded summer programs to target pupils who have experienced learning loss since 2020, O’Leary said there has never been serious discussion about weekend classes to tackle catch-up.

Twenty-six months into the COVID-19 pandemic, covering staff absences continues to be a major challenge for schools, he said.

“While the Public Schools Act makes allowance for teaching on Saturdays, utilizing such an approach would require widespread consultation as this impacts significantly upon families,” a department spokesperson wrote in an email.

The spokesperson noted instruction continued via remote and blended learning when students were unable to attend face-to-face classes.

Since 2019-20, all Manitoba schools were in remote learning for a total of 53 days. The ability to actively participate in distance education has varied dramatically, based on access to reliable internet, computers and, among younger students, parent support.

In a report released last month, the auditor general found Manitoba Education was not prepared to address COVID-19, due to the absence of a comprehensive emergency management program and absence of forethought on remote learning implications.

The 2007 document includes three brief references to distance learning and a single mention of “work-at-home” options.

“High speed, reliable internet is something that, one would hope — if (emergency remote learning) had been on the radar in the last 10 years, would’ve been remedied pre-pandemic, as opposed to reactionary,” said Alan Campbell, president of the Manitoba School Boards Association.

Campbell acknowledged limited planning in the lead-up to 2020 prompted government officials and stakeholders to scramble to set-up a chain-of-command structure for decision making that could accommodate local needs. Now, he said, communication between partners is better than it was before COVID-19 — one of many pandemic takeaways he hopes will remain the status quo.

The province’s 15-year-old guidelines consider key pandemic challenges to be employee and student absenteeism, classroom transmission, psychological stress and low morale, additional expenses, and a permanent loss of corporate knowledge because of the death toll.

In order to manage staffing shortages, it suggests divisions not only draw from substitute pools, but also use administrative personnel, retired educators, parents, education students and volunteers to assist teachers. Combining classes or schools is listed as another temporary solution.

An excerpt from the booklet says divisions may consider deferring staff leaves for professional development, vacation or other non-health reasons to meet coverage needs.

Given employees who have recovered from a virus will be immune to a particular strain, they could assume higher-risk responsibilities in schools to protect others, it notes.

The guidance indicates school closures should be a local responsibility “as much as possible.” And when they are required, schools should give parents as much lead time as possible, describe the reasoning behind the decision, and provide “a realistic estimate” of a closure, according to the guidance.

“Open, honest communication will foster better working relationships, co-ordination and co-operation and will help create confidence and alleviate fear, disruption and inconvenience,” it states, while noting leaders should talk with parents about their crisis expectations and needs.

The guidelines indicate people benefit from receiving information from an official source before hearing it informally in the community or from unofficial school sources.

Christine Van Winkle, a University of Manitoba professor with expertise in emergency management, said people also benefit from being provided with decision-making rationale during an emergency — something she said, as a parent, she feels has been lacking.

“There’s communication in terms of what’s happening (in schools), but not in terms of why it’s happening,” said Van Winkle.

As pandemic conditions improve, the 2007 report recommends school leaders organize ceremonies to remember people who have died, implement in-class programs to help students deal with stress, and identify community resources to help families cope with losses.

It notes a pandemic may include various waves “and last up to two years.”

The education department is currently in the process of working with stakeholders to update business continuity plans, develop an emergency management plan, and review its 2007 guidelines to reflect lessons learned since 2020. The incident command structure will remain intact, according to a spokesperson.

“There’s a lot of opportunity for emergency management, coming out of the pandemic, to become more mainstream and less in-the-shadows,” said Jack Lindsay, an associate professor of applied disaster and emergency studies at Brandon University.

Lindsay said the best practice for preparedness is an ongoing emergency management program overseen by a professional — but that requires more will and resources than simply updating a written plan that will collect dust.

“The advantage, financially, is spending some money every year rather than getting hit with a big bill and the potential tragic loss of life or infrastructure,” he said.

Noting it is not uncommon for emergency plans to be “dusty binders,” Van Winkle echoed those comments.

“Emergencies and disasters will happen,” she said. “The more diverse planning we do early on means the more prepared we’ll be for the unexpected. We might not be able to foresee every possible situation, but maintaining an openness to what’s possible allows us to maintain flexibility in responding.”

maggie.macintosh@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @macintoshmaggie

Maggie Macintosh

Education reporter

Maggie Macintosh reports on education for the Free Press. Originally from Hamilton, Ont., she first reported for the Free Press in 2017. Read more about Maggie.

Funding for the Free Press education reporter comes from the Government of Canada through the Local Journalism Initiative.

Every piece of reporting Maggie produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.