The weary and the resilient They’ve left behind family and their homes but the millions of war-ravaged Ukrainians who have sought refuge in neighbouring Poland are far from defeated

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/04/2022 (1334 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

RZESZÓW, Poland — From the outside, the guest house on the edge of Rzeszów looks quiet, tucked on a narrow road that meanders past quaint homes nestled beside sprawling green gardens. A few cars are parked in front, some with Ukrainian licence plates, but the atmosphere here is idyllic and suburban, bordering on rustic.

Ukrainian Refugee Crisis

Posted:

As the world watches in horror the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and as Manitobans prepare to open their arms to refugees, the Free Press has sent writer Melissa Martin and photographer Mikaela MacKenzie to Poland to report on the largest refugee crisis in Europe since the Second World War.

And in any normal time, Rzeszów — pronounced “Zheshoof” — is a laid-back, albeit growing, sort of place. It’s a city of about 200,000 people, a college town in the southeastern corner of Poland, booming lately with business investments and tourism but still far from the hustle of the capital city of Warsaw. It is comfortable, but not famous. Not in a normal time, anyway.

But this is not a normal time for Rzeszów, because Rzeszów sits just 100 km from the border with Ukraine.

Now, all the donated weapons of the West flow through Rzeszów, and much of its humanitarian aid. The airport north of the city hosts a constant parade of foreign military planes, and when U.S. President Joe Biden visited Poland in March, he came first to Rzeszów, where American troops manage the Patriot missile system freshly installed on the airport’s western flank.

On one windy afternoon, a Canadian military cargo plane sits squat and unmoving on the tarmac. It arrived there from North Macedonia the night before, carrying a load of who-knows-what to deliver to you-know-where. Just down the road, the Patriot launchers stand in eerie silence, their backs bristled up and towards an empty sky.

The closer you get to the ground in Poland, the closer you get to the people and the helpers, the easier it is to forget there are forces acting here that are far greater than most of us can readily imagine.

As weapons and aid flowed out of Rzeszów, people flowed in, and just like has happened all across Poland, residents rallied to help. Now, the second floor of a mall in the city’s downtown has been transformed into a shelter with 500 beds; and now, when you open the front door of the quaint guest house on this quiet road, a wave of gleeful noise rushes out.

It’s just after lunchtime, and the dozen or so children who live at the guest house are full of energy. In the crowded common room that serves as kitchen, dining room and playroom, babies crawl around the floor, while toddlers zoom on scooters and older children toss balloons back and forth. Mothers mingle around the edges, watching the kids play and chatting.

Girls in their tweens listen to music and giggle; boys the same age relax languidly on couches, absorbed in their phones. The din of laughing children, squeaking toys and clinking dishes is, at first, overwhelming. But there is also a sense of something warm and familiar, like some ancestral maternal village where women share the work of childrearing together.

From a couch, Liliya Baran reaches to stop her two-year-old daughter, Daryna, from pawing at a photojournalist’s camera.

“No, no, don’t touch,” Baran chides her daughter gently, in English. “It is very expensive.”

Before the war started, this guest house was empty. But as millions of refugees streamed into Poland, many of them coming through Rzeszów, the owner, along with a group of residents, decided to turn it into a shelter for those fleeing Ukraine. Since then, more than 80 guests have come to stay, mostly women with young children.

The length of their stay varies. Some are waiting for a visa to go to other countries — the United Kingdom, mostly — while others, particularly those from the western part of Ukraine, where Russian troops never penetrated and airstrikes are less common, started making plans to go home after Russian forces fully withdrew from the Kyiv capital region.

Baran falls into that category, too. She’d fled her hometown of Lviv on the first day of the war, bringing her three children — all under age six — with her. In Rzeszów, she first found a place to stay with a Polish family; but soon she met a woman who knew about the guest house, and that is how she came to move her young family into one of its rooms.

At first, Baran says with a laugh, she also found the noise a little overwhelming. But she saw that her kids were thriving, with lots of toys and other kids their age to play with. And they had a room to themselves, with its own bathroom, and some of the tween girls like to help take care of the smallest kids, so it was hard to imagine a better place to stay.

There are hard times, of course. Just a few days earlier, they’d read the first reports of civilian massacres in Bucha, north of Kyiv. Though Baran has tried to limit how much news she consumes about the war, that day was difficult: everybody at the guest house was talking about Bucha, she says. But they helped each other get through.

“Everybody is connected to each other right now,” she says. “They understand now, what is life.”

Baran is ready to go home. Her mother was set to arrive at the guest house that day, to help with the kids for a week or so; but then, they were planning to return to her parents’ village near Lviv. She could go nearly anywhere in the world, if she wanted. But she’s lived abroad before; now, all she wants is to be back in her country, with her family, to stay.

“We lived a good life in Ukraine,” Baran says. “People are saying that they don’t want anything, they just want to go back home and lay down on their own beds, to have that life they had before. This is all that they want. Everybody wants to go back. I want to go back.”

By the time this story runs, she may already be home. But not everyone here will see their own beds so soon.

Nearby, Kateryna Kovalova kneels on the floor, watching her daughter play. She’s also come to love the guest house, and the support it contains: “I like very much, and people here are very generous,” she says. “I’m really impressed. When we passed the border, we were afraid, but now we see that all the people in the country are ready to help us.”

Kovalova is from Donetsk, in the heart of the long-contested Donbas region on Ukraine’s southeastern edge. In 2014, when separatist forces backed by Russia declared Donetsk the heart of their breakaway republic, Kovalova and her family moved just a few kilometres north, to the tiny city of Avdiivka, which remained near the front lines of the separatist war.

“All these years, we were right beside the war,” she says.

Despite the tension splitting the region, which flared up in deadly violence in Avdiivka in 2017, it was a good place to live, Kovalova says. Its main industry is a coke plant, the largest in Ukraine, which provided good wages and afforded a decent standard of living for Avdiivka’s people, she says; still, she hoped she’d be able to return to Donetsk someday.

Now she flips through photos on her phone, showing pictures of the school where she works, ravaged by a bomb that struck its entrance — “It’s not a military object as you can see,” she says, shaking her head sadly — and of her friend’s house, which has been shredded into an unrecognizable tangle of debris.

“We are sitting with you in a safe place, but I know the house of my friends in Avdiivka,” she says. “There’s no place to live for them now. And as I read stories of our (mayor) — every day, a lot of shelling. They want to destroy everything. Before, I hoped to come back to my place, but now I’m not sure. We are not sure that we have the place to come back.”

“Before, I hoped to come back to my place, but now I’m not sure. We are not sure that we have the place to come back.” – Kateryna Kovalova

For now, she is trying to make the best of it. Back in Avdiivka, she teaches English, so she’s started classes here for the kids; while we chat, one of the teen boys comes up to ask when the next lesson is. And she’s glad to talk to reporters, she says, because her city is not very big, and she wants the world to know about Avdiivka.

I ask her how she’s doing. She starts to answer, but tears catch in her throat and, for a moment, silence her words.

“All the people here have their histories, and sometimes we share our histories,” Kovalova says, after a long pause. “Everyone wants home. Everyone is waiting for something. But in their soul everyone wants home, wants to come back, and wants to go on their land, with their family.”

But for now, some of them must stay here, at the quiet guest house surrounded by green fields, where volunteers from as far away as Mexico and Spain come to play with the kids, to give the mothers a break. Where the Rzeszów residents who created this haven make sure they have food, and clothes, and everything they need. Where at least they know they are safe.

“Please write down in your newspaper about Polish people,” Kovalova says. “It’s something incredible, what they really do for Ukrainians. And please write down that Ukrainians are very thankful. We are very thankful for everything they do, for everything all the countries do.”

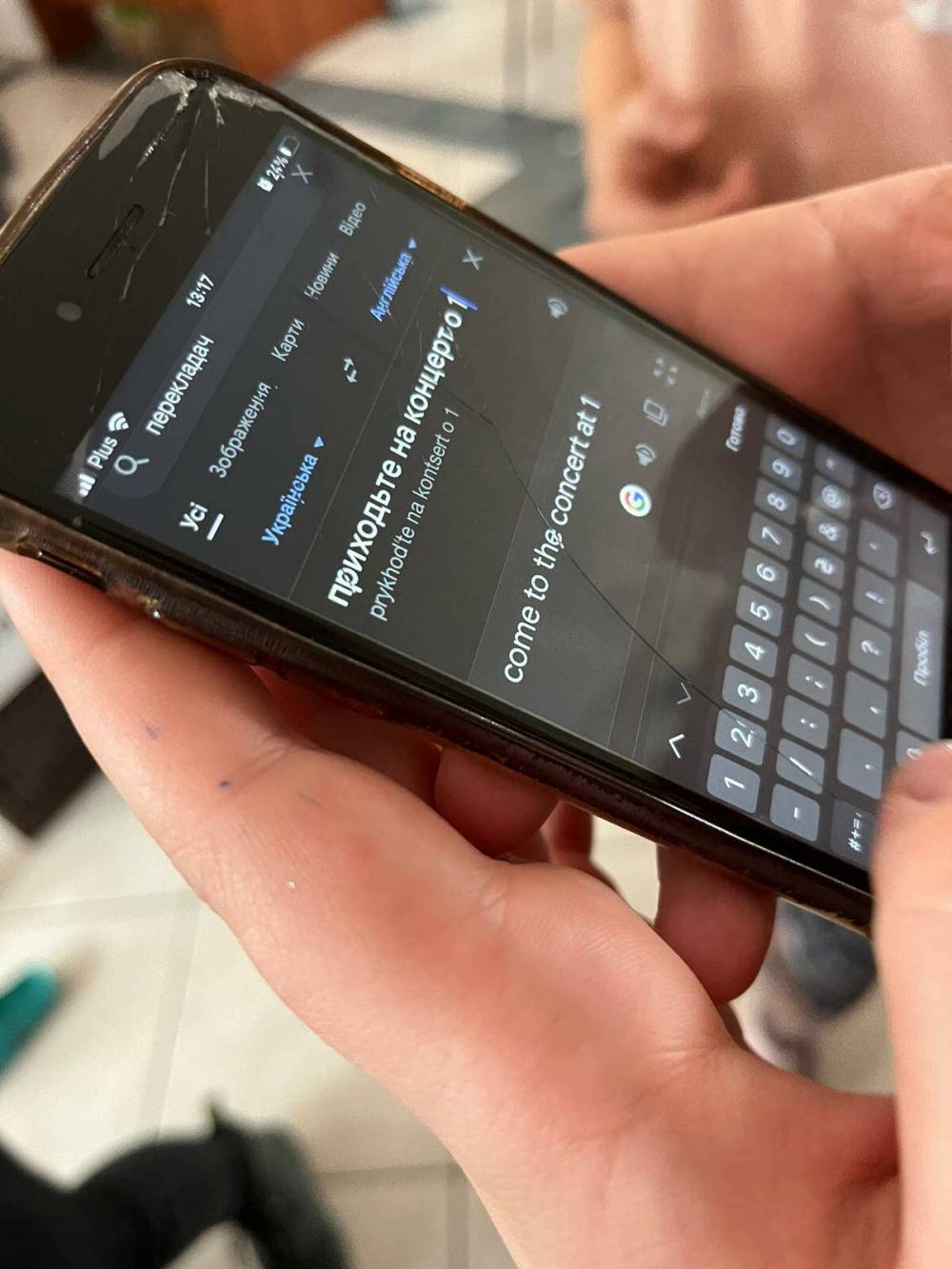

The afternoon is getting longer, now. It’s nap time for the younger kids. But as we turn to leave, a tween girl wearing a smear of golden eyeshadow runs up and makes an urgent statement in Ukrainian. I tell her I don’t understand, so she wrinkles her nose, pulls out her phone, opens a language translation app and quickly taps out a message.

“Come to the concert at 18:30,” it says.

We came to Poland to bear witness, not to a war, but to the everyday lives that are caught on its fringes. We came on behalf of a province that has itself been indelibly shaped by thousands of lives that once left Ukraine. We came knowing that these ties of family, culture and faith still thrive in Manitoba, and so Ukraine’s stories are inextricably bound with our own.

And we came to tell the stories of a sudden and sweeping mass movement of people, one that started the morning the war did and continues over seven weeks later. And if you want to see what that mass movement of humanity truly looks like in Poland, you have to start at the train stations.

In a way, the train stations begin to blend together, from the large terminals of Warsaw or Krakow to the cozier domed hall of Przemyśl, just 13 km from the border. Some are big, some are small. Some echo the stately old European architecture of their cities, others are sleeker and more modern. But all are filled with Ukrainians, on the move to somewhere else.

This is what you see in the train stations: soldiers. Priests. Police. Volunteers in yellow vests, sometimes with their names scribbled on the front in black marker, sometimes with flag pins indicating what languages they speak. Volunteers to hand out fruit, volunteers to carry refugees’ luggage, volunteers patrolling the terminals distributing pet food and diapers.

And there are signs, more than the mind can process at once, taped to every wall, column and window. Signs for a free bus to Lithuania, to Italy, to Spain. Signs for information on how to get visas for Canada or the United States. Signs for hot meals, for a clinic for pregnant women, for assistance from the Japanese government, for the United Nations.

There is a sign for a Facebook group of Polish volunteers, who help people with pets find transportation and places to stay: “Don’t leave your little friend!” it says. There are signs reading “Safety Rules For Those Fleeing The War In Ukraine,” a nod to fears of human trafficking. Signs for a store that sells cigarettes, for free SIM cards, for a place to stay, for everything.

Above all, there are the people. They come and go from all directions, mostly women towing children and countless pets in small carriers. Some wait on train platforms, or in chairs; others sit quietly, unsure what to do until a volunteer notices and goes over to help them. Here and there, elderly women lie on the floor, on beds of folded-up blankets.

Of everything I see in Poland, it is the train station scenes that will stay with me the longest. They are chaotic, and emotional mostly in the staggering scope of them, the sheer volume of human displacement. As I shoulder my way through the jammed hall of the station in Przemyśl, I think: this is day 43 of the war, and there is still this much movement.

One can only imagine what it was like at those stations, one month ago.

I came here hoping to tell the stories of people, but here, at the source, it becomes overwhelming. Everyone in these stations has a story. Some are more immediately painful than others. But in the broadest strokes, every story is the same: they had a life in Ukraine, and now they’ve had to leave it, and that trauma bleeds into the ennui of long journeys, and longer waits.

Evening falls over the guest house in Rzeszów. After a dinner of soup and sausage, the residents put away their plates and begin to gather for the big show. The tween girls have been preparing this concert for days, Liliya Baran says with a laugh, choosing songs and planning the order of performances. Something to show off the talents they’d learned in Ukraine.

As the minutes tick down to showtime, the stars of the show practise their dance moves in the play area. One of the Polish volunteers sets up a camera to livestream the concert to Facebook, so that the refugees’ families still in Ukraine can watch. Mothers settle into couches, bouncing their babies on their laps, while the toddlers heedlessly tumble all over the floor.

While I wait, I admire the artwork pinned just outside the door: a traced outline of small hands, one coloured in the blue-and-yellow of the Ukrainian flag, the other in the white-and-red of Poland. Beside it is a more mundane notice, written in Ukrainian, featuring a cartoon doctor reminding the children to wash their hands.

Then I turn around and almost collide with a slight girl who is standing behind me, gazing up with liquid brown eyes.

Her name is Nina, and she is 14 years old. She speaks remarkably good English for her age; she’s been thinking lately that someday, she might like to become a translator. Her family is from Zaporizhzhia, in southeastern Ukraine; this is her first time out of the country, and though she is hungry for the world, right now she just wants to go home.

It’s “very bad” near her home now, she says. That is how all refugees tend to explain the news of the war from where they have come. Some places are “not bad,” others are “very bad.” They don’t often explain more, and I never ask them: those lone words already transmit enough pain.

Looking around at all the frolicking children, I wonder if it isn’t hardest for someone like Nina. The babies are too young to know, and won’t remember. The younger kids are still shielded from the horror of war by their parents, at least a little. But Nina isn’t. She’s old enough to understand everything, but too young to have the tools adults do to get through it.

All she can do is stay strong, and try to keep doing the hard work of simply growing up.

Yet through this, she hasn’t lost the curiosity of a girl on the cusp of becoming. She loves to talk about music — her favourite band is Nirvana — and the beautiful places in the world. She dreams of visiting Los Angeles, and seeing the beaches and the Pacific Ocean. She loves mountains, so I show her photos of Lake Louise on my phone.

When the concert begins, Nina sits cross-legged on the floor, eagerly coaxing me to join her.

The tween girls place a portable speaker in the play area, and key up an eclectic mix of music. The hit song Believer by Nevada rock band Imagine Dragons is followed by Trymai, a 2015 tune by Ukrainian folk-pop star Khrystyna Ivanivna Soloviy. Nina types in the Ukrainian song titles on my phone, so I can find them later.

In the middle of the play area, the girls dance to the beat. They do cartwheels in unison, and break into dance moves made popular on TikTok. Sometimes, they sit on the floor and sing in unison. After each performance, the audience breaks into a round of delighted applause, and the girls skip back to their places on the sidelines, beaming with pride.

An hour or so later, the concert is over, and the common room begins to fall quiet. The owner of the guest house hands out Kinder Egg chocolates; upstairs, Liliya Baran begins to put her children to bed. It’s time to leave the guest house, and all of the joy and the laughter that thrives here, despite — or perhaps in spite of — the war.

Nina follows myself and my colleague, photographer Mikaela MacKenzie, to the door. As we put on our coats, she throws her arms around us.

“I will miss you so much.” – Nina

“I will miss you so much,” she says.

We add each other on Instagram. I tell her she will always have a friend in Canada and that I hope she will see the beaches of Los Angeles someday. As the days pass, she sends me messages, excited to report that they’ve had visitors from America and Holland, and that she was able to translate for those aid volunteers when they came.

If there is one word that can summarize the conversations we have with Ukrainian refugees, from Warsaw to Rzeszów to the border, it would be “undefeated.” They do not tend to be overly optimistic about the war — they are all aware of where things are “very bad,” and most we meet expect the fighting to last for months — but they are all determined to outlast it.

At another refugee centre in Rzeszów, the second floor of a mall owned by a colourful local cardiologist and businessman, a warren of glass-fronted shops has been turned into a village of 500 cots. There is a play area for the kids, a free store full of clothes, and a small army of Polish volunteers ready to help with everything from food to simple companionship.

There are people here from all over Ukraine but particularly, as of late, the eastern reaches of the country, from Kharkiv or Mariupol or Kherson. Most stay for a few days, before figuring out where to go; but few of them want to leave Poland, says translator Julia Khrystenok, who herself arrived as a refugee from Kyiv and decided to stay and help.

“Most people don’t want to leave their houses, and they are staying to the end,” she says. “But they are really disappointed. I also would like to return, and I would like to help, to do something, not to sit and think about the situation… but I would like to go back. I have a good house. I’m not ready to start from zero.”

Khrystenok leads us to a long folding table at the centre’s canteen. She disappears for a few moments, and when she returns she is accompanied by Olena Petrychenko, a woman in her 60s who had fled from a village in central Ukraine. Petrychenko sits down shyly, but when she starts to speak her story tumbles out so fast that Khrystenok can barely keep up.

She tells us about how she went from her town to Lviv, and then from Lviv to Warsaw with her grandson. After dropping him off at a safe place, she tried to return to Ukraine, but after a fresh round of airstrikes a relative urged her to stay in Poland for a little while longer. So Petrychenko settled into life at the refugee centre, which now, she says, “feels like home.”

Still, it’s not like the home she knows. She and her husband worked hard to build their house with their money. They have a big garden, and when she talks about it her eyes light up and her face grows animated. They grow many vegetables: potatoes and carrots and tomatoes. They should be preparing for sowing right now, which usually happens just after Easter.

Petrychenko has much to say about the situation. She assesses how important it was that Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy decided to stay in Kyiv, when the United States and France were offering to evacuate him from the country; she speaks of her hopes that foreign powers will enforce a no-fly zone, which the United States has firmly kiboshed.

Above all, she speaks about her anger towards the Russian Federation. (Somewhere in the middle of that topic, she quotes a line by a Ukrainian soldier taken prisoner on the first day of the war that became famous as a rallying cry: “Russian warship, go f—k yourself.”) And she speaks too about what is helping her and everyone she knows get through.

“Ukrainian people now are very connected, and we are also very strong,” she says. “We have great courage, and we’re very brave. We really know that we are brave people. Even when we hear some bombs, we will say… ‘just the next bomb and we will leave our house. OK, we will stay now, and we’ll leave after the next bomb.’”

Later that night, I text an old friend to ask if this sort of openness is typical among his people. I had come expecting to have only the most delicate conversations, but instead I find that nearly every displaced Ukrainian is friendly and open, and quick to voice blunt and varied thoughts about their government, the war, refugee life, and especially Vladimir Putin.

Is it the situation, I ask my friend, or is it part of the culture to be so unvarnished, so frank, so outgoing?

“Probably a bit of both,” he replies. “But most Ukrainians will tell you what they’re thinking.”

After the youthful concert at the guest house is over, a man named Sergiy wanders outside and lights a smoke.

Sergiy speaks no English. My Russian consists of a handful of disjointed nouns, pronouns and verbs, rarely combined in the correct ways. Nobody who can translate is standing nearby. Yet somehow, to my surprise, we manage a conversation that is, if not coherent, at least moderately successful in transmitting basic information and a little camaraderie.

As a result, this is everything that I know about Sergiy.

He is from Borodyanka, a settlement of about 13,000 people northwest of Kyiv and just 30 km outside of Bucha, where the Russian retreat revealed civilian bodies dead in the streets. He’d driven his family out of Ukraine in a battered green Soviet-made car that looks on its last legs; in the windows, like many who fled, he’d taped signs reading “dity” — children.

Sergiy’s wife gave birth to their fourth child here in Rzeszów just two weeks ago.

He’s a gregarious character. He considers both Russian and Ukrainian his first languages, of which he seems rather proud: one of his parents spoke one, he explains, and the other the other, so he grew up equally with both. What he most wants to show me is a video of himself singing Shalom Aleichem with Israeli aid workers who visited, not long ago.

Sergiy sang along lustily, clapping his hands with the gusto of a man who is no stranger to late-night singalongs.

Sergiy loves to sing. At the concert, when the girls started performing Oy U Luzi Chervona Kalina, a folk song that has taken a renewed popularity thanks to a video of a Ukrainian rock star-turned-soldier singing the tune in Kyiv’s streets, Sergiy sang along lustily, clapping his hands with the gusto of a man who is no stranger to late-night singalongs.

When my colleague asks if she can take a photo of him with his car, he poses with his foot on the back bumper and his index finger raised in the air, like a champion. Later, I see a photo from a Polish newspaper, where he’s doing the same thing with his hand. Undefeated, I think. There’s that word again.

Sergiy finishes his smoke. His wife comes to chat for a bit, then takes him back inside. He waves warmly. “Bye bye.”

I am glad I do not know enough Russian to ask what he’s heard about conditions in Borodyanka. “Very bad,” I assume. A few days later, pictures emerge of that area showing streets choked by rubble and a tall apartment block gouged down the middle by bombs. I hope, that someday, Sergiy gets to load his family in their battered old Soviet car and sing their way home.

The border is quieter now than it used to be. At the crossing near Medyka, one of the main arteries from Poland and into the city of Lviv, there have lately been more volunteers than people freshly arriving. Most of the buses that pull up in front of the crossing are carrying a small but growing trickle of people heading back to Ukraine.

A man wanders by, wearing a Ukrainian flag draped over his shoulders. On it, he has written just one word: Mariupol.

At a picnic table in front of the footpath to the border, outside a tiny restaurant serving pork cutlets and salty soup cooked by a pleasant, if harried, lone worker, a woman slips into an open seat beside us. She introduces herself as Svitlana, and she too is headed home, to a city in western Ukraine that she’d fled shortly after the war started.

She found a place to stay in Warsaw, but it always felt strange. After a couple of weeks in Poland, she suddenly remembered the 2004 movie The Terminal, which featured Tom Hanks as a man who was forced to live in an airport for months after his country suffers a military coup mid-flight. A liminal life, paused in transition, neither fully embarked or fully arrived.

“Then I understand, I am Tom Hanks in this situation,” Svitlana says, and laughs brightly.

“In normal situation, you understand, it is all ‘my work, my business.’ But in this situation matters only one thing: save my country. We want to have country.” – Svitlana

We sit for about 45 minutes, chatting about everything that has gone on. About how she, like many refugees here, think Ukraine will be “stronger, 100 per cent” after the war. We chat about Zelenskyy’s performance on the world stage, and about how she thinks this conflict has, and will, change the future of Ukraine.

“We don’t understand exactly what spirit we have,” she says. “In this situation, it’s more. Maybe in (the war which started in the Donbas region in 2014), it’s not so much passion. But nowadays situation, it’s co-operation… and we have some spirit. I love my country, but… early on I don’t understand how much I love, how much I want to have (choices).

“Ukrainian people are like any other people, but Ukrainian people want to choose freedom first of all… we love our country. On 24 February, in one day… terrible stress war. But we make to save country. In normal situation, you understand, it is all ‘my work, my business.’ But in this situation matters only one thing: save my country. We want to have country.”

Svitlana finishes her soup, stands up, and readies her luggage to go. She reaches to shake our hands one last time.

“If it will be safe some day, you may go to Ukraine,” she says: an invitation.

Then she’s gone, vanishing into the tangle of aid tents and yellow-vested volunteers that line the last footpath to the border. On the other side, her husband is waiting to take her home, back to the life she had put on hold. We watch her as she makes her way to the gates of the crossing, where soldiers stand guard. She never once looks back at Poland.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Monday, April 18, 2022 10:27 AM CDT: Amends reference to cargo plane in story and cutline

.jpg?h=215)