Public can handle ‘highly technical’ data

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 01/02/2022 (1405 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

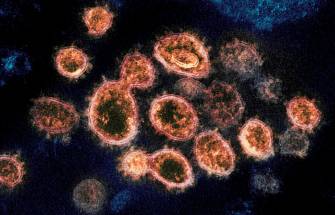

Not everyone in Manitoba is regularly tested for COVID-19. But all of us use toilets.

The universality of our contributions to the flow of sewage makes the testing of wastewater for COVID-19 a welcome tool for measuring the spread of the virus. It’s particularly important during this time of diminished testing results, as Manitoba does not record the number of people who self-diagnose with rapid tests.

Many provinces use wastewater-sample data to inform the public about the prevalence of the virus, but in Manitoba, that data remains hidden from the public. When the Free Press asked the province last week for the latest statistics related to wastewater monitoring in Winnipeg, a government spokesman declined.

To be clear: Manitoba has the data. Wastewater samples have regularly been taken at three locations in Winnipeg for nearly 18 months by the Public Health Agency of Canada, with the results given to Manitoba public-health officials.

When asked why Manitobans can’t see the data, a government spokesman said last week the information was “highly technical.”

It’s understandable if Manitobans feel insulted that our cognitive faculties are apparently deemed insufficient to comprehend information of a type that is regularly shared in other provinces. For the record, this province has scientific and medical institutions that are highly regarded, and a thriving laboratory industry that includes the National Microbiology Laboratory. Some of us even understand big words such as epidemiology.

When asked why Manitobans can’t see the data, a government spokesman said last week the information was “highly technical.”

Perhaps the problem isn’t that the Manitoba public is incapable of understanding technical details. Perhaps the problem is a government that has often shown scant regard for the public’s right to know.

During the pandemic, media briefings have frequently descended into a sorry spectacle of government ministers and health officials obfuscating and sidestepping inquiries seeking unfiltered information that would let Manitobans weigh the government’s response to the pandemic. For example, the government has repeatedly withheld statistical modelling that offered an informed prognosis of the pandemic’s likely path.

As recently as last week, a spokesperson for the health-sector team in charge of pandemic response was asked how many surgeries were cancelled in January, which is important information to evaluate how the Manitoba system is coping with this unprecedented demand. The spokesperson said they didn’t know, which indicates two scenarios, both unsettling: either they actually don’t know this crucial information, or, more likely, they know but don’t want the public to know.

As a gatekeeper of information, the government’s hoarding of relevant information has cultivated a relationship of distrust with citizens that is at least partly responsible for the approval rating of Premier Heather Stefanson dropping to 21 per cent, according to the Angus Reid poll released Jan. 17.

Wastewater data is particularly important because the provincial government has largely given up trying to track the number of cases of COVID-19 by other means.

Wastewater data is particularly important because the provincial government has largely given up trying to track the number of cases of COVID-19 by other means. Manitoba schools and daycares are no longer notifying public health of positive cases. Individuals with COVID-19 symptoms are told to test themselves with at-home rapid antigen tests, with no government reporting mechanism in place if citizens want their positive tests recorded.

Into this void of data, wastewater testing data can show whether community infection rates are increasing or decreasing. Without credible reason, Manitoba officials are keeping the information from public view.

Chief provincial public health officer Dr. Brent Roussin said his office is working to make wastewater surveillance data public, but he said the way the federal agency has reported results has delayed publication. If the Manitoba officials need guidance, they can ask the many other jurisdictions that apparently respect the ability of their citizens to comprehend wastewater data, even when it’s “highly technical.”