Voices from the virus Seven sick and tired Manitobans in various states of recovery talk about their COVID-19 experiences over the past month

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/01/2022 (1427 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Tens of thousands of Manitobans have been infected with COVID-19 in the past month, but every case in unique. Some have a light case of the sniffles, while for others it’s a brush with death. The long-term impact can range from a new outlook on life to financial ruin.

The Free Press spoke with seven people who tested positive during the rampaging Omicron surge, and asked each of them what they want the public to know.

Kevin Settee

A body ache that reached into Settee’s joints was the filmmaker’s first sign something was wrong. For two days, the 31-year-old kidney-transplant recipient was feeling off. And then people close to him started to test positive for COVID-19.

“Because I’m immunocompromised I don’t really go to too many places,” he says, a persistent cough punctuating the phone conversation. “I avoided being around people as much as I could.”

Settee, who was triple-vaccinated, caught COVID-19 in late December along with tens of thousands of other Manitobans as Omicron variant spread out of control.

With a sore throat, runny nose and headache, he went to a testing site near his home outside of Winnipeg, but was turned away because he didn’t have an appointment.

“It’s the middle of the damn pandemic and you can’t just walk in and get a test,” he says.

He then drove into the city to get tested but was discouraged by the long lineup, so he returned home, fairly certain he was infected. His mother was able to find a test kit and dropped it off. He was positive, his seven-year-old son was negative.

As his symptoms worsened, Settee explained to his son that he was sick and would need help to fight the virus. Friends and family dropped off food and other items and offered to watch his son so he could rest.

Five days in, Settee awoke during the night, coughing with a heavy chest and shortness of breath. Feeling panicked, he had the urge to go to the hospital but a call to Health Links helped to calm him down, the nurse recommending he go to an ER if breathing became more difficult.

He called his transplant clinic the next day and a doctor referred him for monoclonal antibody treatment. He received a call two days later from Grace Hospital, dropped off his son to stay with a friend and went for treatment.

“Within a couple hours of that treatment I was starting to feel a little bit better and slowly got better as the hours went on, days went on,” he says. “The next day I had energy in my body. It made a difference, for sure.”

”The next day I had energy in my body. It made a difference, for sure.”–Kevin Settee on monoclonal antibody treatment

Settee says his experience with COVID-19 has caused him to reflect on an expression used by Indigenous activists and people in the climate-justice movement: when the Earth is sick, people will get sick, too.

“That really stuck out to me and made me think, too, that things aren’t going to get any better,” the Fisher River Cree Nation member says. “We kind of have to get used to it and figure out how to work together as a community.”

Settee says he’s incredibly grateful for the help he received from his network of friends and family.

“I’m doing that, as well, with my friends now that I’m feeling a lot better — dropping stuff off to people, delivering food, delivering medicine and just kind of paying it forward,” he says. “That’s what we’re going to need moving forward.”

Erica Silk

By the time Silk got infected, COVID-19 had already cost the 26 year old three different jobs.

The Winnipeg server developed a sore throat and aches on Dec. 18, and got a test appointment the next morning.

She was one of the last to get results within 72 hours, just before the laboratory backlogs overwhelmed the system, causing the province to pivot and offer only rapid tests to most people.

Between her test and getting the result, Silk learned she’d been in contact with a friend just before they both developed symptoms.

The hour-long call from public health was surreal; questions included how often she’d been to the gym and whether people she’d visited a restaurant with were wearing masks.

“I know the questions they’re asking are about safety, but in a way it felt judgy,” she says. “I just assume they follow the same script for everybody… but it just felt (like) shaming.”

Silk lives with her parents, and the province’s guidance for containing spread includes limiting the use of shared objects.

How that advice is delivered can vary.

“They asked me if I was going to be using the same cutlery as everybody else, and I said I have to — like, I don’t have plastic cutlery. And then I got a lecture on it. And then I got re-asked if I was going to be using plastic cutlery. And I said, ‘I still don’t own plastic cutlery.’ And I was also told not to produce any garbage, so I was confused,” she says.

Even worse was informing her friends they’d been exposed, but having no information or a website address to pass along on what they should do, beyond staying home.

”They asked me if I was going to be using the same cutlery as everybody else, and I said I have to — like, I don’t have plastic cutlery. And then I got a lecture on it.”–Erica Silk

Silk had the typical Omicron symptoms of headaches, exhaustion and a fever, but there was no impact on her sense of smell or taste. Her fever jumped from mild to 40 C in just 90 minutes.

“I was kind of terrified because it happened so fast,” says Silk, whose father was infected, despite her best efforts to stay away in her room.

She’s been recovering well, but lost out on what is traditionally the most profitable week of the year for restaurant staff during the Christmas rush.

As an hourly worker who doesn’t get paid sick days, she’s among those hardest-hit financially in the pandemic: young, female and working in the hospitality industry.

Silk was living in the United States when COVID-19 hit; she lost her visa when her workplace downsized and also lost two jobs in Winnipeg. Getting infected has landed another significant blow to her bank account.

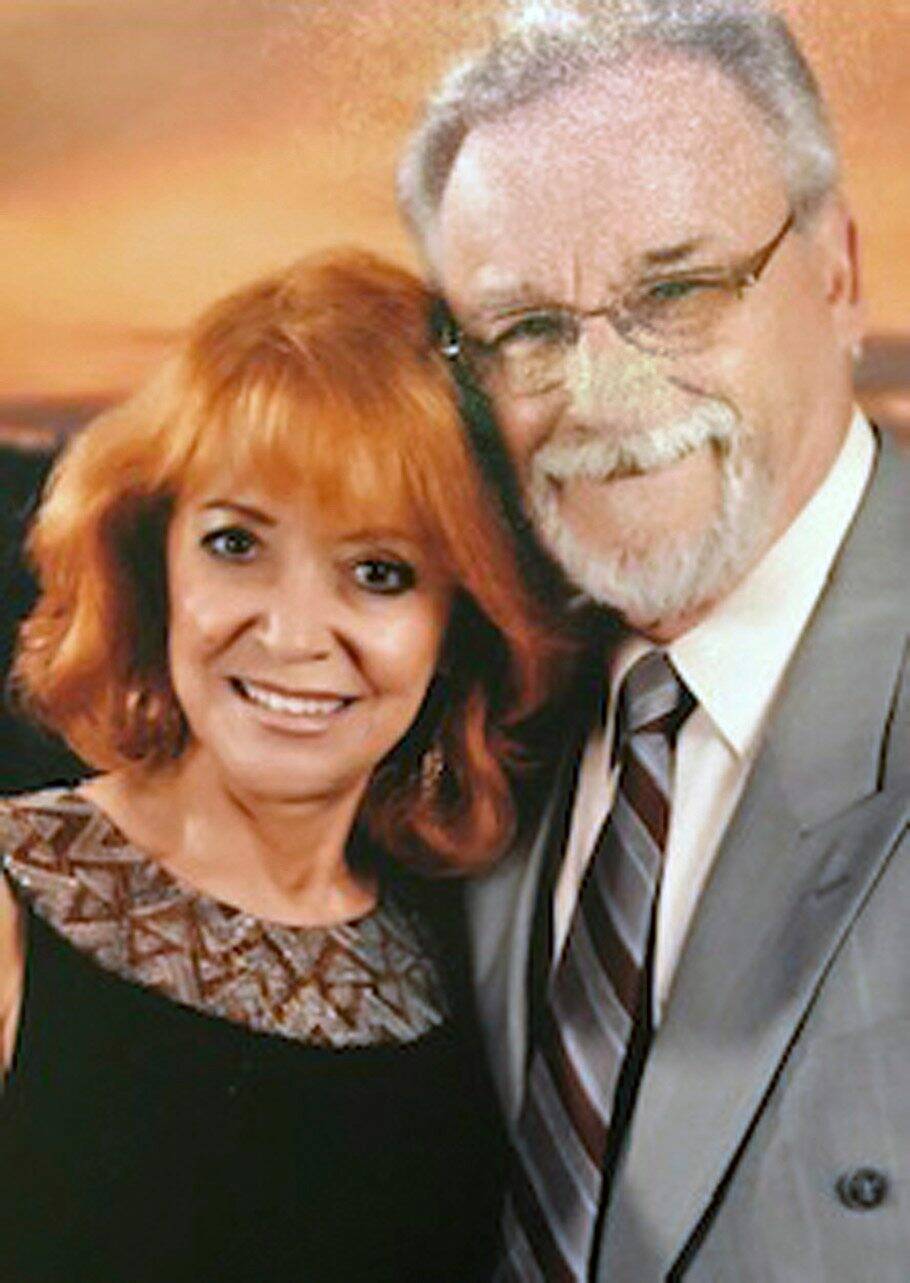

Liz Symmons

Lunch at Salisbury House was one of the last meals Symmons enjoyed before losing her sense of taste to a punishing case of COVID-19.

“I didn’t think that would be as bothersome as it is,” the 73-year-old St. Vital resident says. “I was so happy I could eat again, but it’s like eating cardboard.

“You can’t taste a darned thing.”

Symmons and her husband Al, 74, suspect they were exposed to the Omicron variant during that fateful lunch just before Christmas.

A day after dining at the restaurant not far from another patron with a terrible cough, they both felt ill.

“I just wish we’d left right away,” Symmons says.

With rapid tests confirming their COVID-19 status, the fully vaccinated couple hunkered down at home, drinking tea and eating chicken or beef broth while tending to fevers of 39.5 C.

The horrendous vomiting, painful muscle aches and brutal headaches — far worse than any other illness she had experienced — lasted about 10 days, Symmons says.

Her sense of smell and taste haven’t returned.

Over the course of their illness, Symmons says she was frightened her husband Al would need to go to the hospital because his respiratory symptoms were severe and he’d had a previous bout of pneumonia. The two kept in touch with their doctor, who advised them on how best to manage their symptoms at home.

Her pharmacist was also willing to drop off supplies. Food wasn’t much of a concern; neither of them had an appetite.

Symmons says she tries to not think about how bad things would have been if they had not been immunized.

”Be very careful, because it’s not as a lot of people are saying, that it’s just another flu.”–Liz Symmons

“We’re feeling pretty good… we’ve come through the worst of it and now we’re just happy to be feeling better,” she says. “Our two little dogs are happy we’re up and running again.”

Despite studies showing the Omicron is less severe than the previous-dominant Delta variant, Symmons says it’s nonetheless a very scary illness for a lot of people, including those who are elderly or have other health issues.

She calls the current public-health approach of encouraging people to reduce their personal risk rather than increasing restrictions is the government “running scared.”

“There are so many people sick that they’re overwhelmed and they don’t know what to do,” she says.

And Symmons urges people to take Omicron seriously.

“Be very careful, because it’s not as a lot of people are saying, that it’s just another flu,” she says. “No, it’s very severe and you really go through hell.”

Dave Heavysege

COVID-19 felt a lot like the side-effects of Heavysege’s second dose of the Moderna vaccine.

“It was not as severe, but way longer lasting,” the 36-year-old geologist says.

He felt a tickle in his throat two days after playing hockey. A teammate told him he’d tested positive.

“We’re on the bench, and we’re not supposed to share water bottles, but I’m sure that happens. And I’m sure guys are spitting,” said Heavysege, whose entire team is vaccinated.

“I thought we were doing everything we could, and I got it anyways.”

The next morning, Dec. 22, he woke up sweating, with a fever. That was followed by congestion and a cough.

He arrived at the Nairn Avenue drive-thru testing site at 10 a.m., but gave up after 40 minutes because the line had barely moved. He knew of a walk-in clinic offering rapid tests, but they had scores of people lined up outside.

There were about 100 vehicles waiting when he got to the Nairn Avenue site the next day at 6 a.m. — an hour before it opened. After 3.5 hours, he got a test; it seemed like only one person was taking nasal swabs, with others filling out paperwork.

“It was really frustrating sitting in that testing line; I don’t understand why there aren’t more hands on deck,” he says.

The results arrived a week later, at which point he’d recuperated.

”Now that I’ve had it, it’s kind of like, let’s get this over with.”–Dave Heavysege

Heavysege lives with his brother, and both got sick as mother flew in from Toronto for a Christmas visit, which she ultimately spent in a hotel.

And his two-week rotation at a mine in Ontario was rescheduled, so he didn’t suffer any economic fallout.

The mine segregates workers to prevent spread, and that means spending a lot of time alone in cars and at workstations, which wears on everyone, he says.

He believes the Manitoba government dropped the ball on testing, and isn’t making the same effort members of the public are in an attempt to contain the virus. And he’s beginning to think everyone is going to end up getting infected at some point.

“I don’t want to put anyone in danger, and I’m not going to become an anti-masker, but mentally it’s like, when is it going to end?” he says.

“Now that I’ve had it, it’s kind of like, let’s get this over with.”

Jey Thibedeau

On the first day of Thibedeau’s winter break, the 59-year-old high-school teacher woke up with a cough and sore throat. She spent the majority of the next 16 days — the entirety of her holidays — in bed.

“‘I was really proud,’ I told my sister on Day 12, ‘I did laundry,’” she recalls. “And then I had to take a nap.”

While Thibedeau got her booster shot several days before her symptoms appeared Dec. 23, it is unlikely she had the benefit of an extra layer of protection prior to contracting the virus. She experienced fever, chills, nausea, respiratory congestion and headaches. Positive rapid antigen and PCR tests confirmed her suspicions.

It got so bad that on more than one occasion, she considered calling an ambulance, but said she did not want to further “burden” an already overwhelmed health-care system.

“I know somebody who had a runny nose and a headache for two days, and that was it, and I’m very thankful for them, but I did not experience that, she says. “I would never want to be as ill as I was, ever again.”

Thibedeau says she is lucky to have been able to isolate in her home and receive support from friends who dropped off groceries.

The drama and English teacher suspects she was infected at work or at a small gathering with friends.

The Winnipegger’s sense of taste has only partially recovered, and her voice remains strained. She continues to deal with extreme exhaustion.

Because of the experience and prospect of having “long COVID” symptoms, she believes there should be additional public-health restrictions. She’s skeptical about the return of 1,400 students to her school for in-person learning, beginning Monday.

”I would never want to be as ill as I was, ever again.”–Jey Thibedeau

Given the high rate of community transmission in the Manitoba capital, she is concerned about the health of her students and colleagues.

“We will be adhering to all of the rules a little more stringently,” she says about what, exactly, will have changed at her school between mid-December and Monday.

Enrolment figures and available space make physical distancing of two metres impossible in her classroom, she says.

Shaneen Robinson-Desjarlais

When Robinson-Desjarlais saw the two red lines representing a positive result on her rapid COVID-19 test Jan. 5, a wave of anxiety washed over the mother of three.

“That was more of what hit me really hard,” Robinson-Desjarlais says. “I was just praying… I do not want to go through what I went through last year. It was just really devastating for our family.”

It was the worst kind of deja vu for the 41 year old, who was hospitalized with the Alpha variant last April just days after giving birth to her third son.

“All those feelings hit me again and it was just that pure anxiety… I don’t want to be leaving my family, I don’t want to get so sick again,” she says.

During her first bout of COVID-19, Robinson-Desjarlais was in and out of the hospital for a month and almost had to be intubated because of low oxygen levels. She recalled bargaining and praying to see her family again. Rehabilitation has also taken time, requiring three months of oxygen therapy after suffering significant lung damage.

With Omicron, Robinson-Desjarlais says she had a runny nose, sore throat, dry cough and a terrible headache. And while she was very sick, she was spared the crushing feeling of not being able to breathe.

“The one thing that really was hard on me the most was the anxiety of just not knowing what was going on inside my body,” she says over the phone while her children can be heard fussing in the background.

“I prayed a lot and thought, all right, I have to have faith that I was really sick before, and that I hopefully have some kind of antibodies in there, and that I have also the fact that I’m double-vaccinated on my side, as well.”

She’s since tested negative on rapid tests and is on the mend, though continuing to feel very weak and fatigued. Her kids all tested negative for the virus, as did her husband, who was the first one in the house to develop a runny nose, cough and headache.

”The one thing that really was hard on me the most was the anxiety of just not knowing what was going on inside my body.”–Shaneen Robinson-Desjarlais

Robinson-Desjarlais is encouraging people to get vaccinated to reduce their chance of needing a hospital bed and commended those working in the health-care system who have had many sleepless nights away from their families.

“I know that there’s this dark cloud over the world right now, and there’s so much fear and so much anxiety, and so much not knowing,” the member of Pimicikamak Cree Nation says.

“Humanity needs to take this as some kind of lesson from what’s happening in our world and to be more understanding of one another, to help one another, to respect one another and to show love and kindness and empathy.”

Kevin Giles

COVID-19 stole precious time Kevin Giles and his family had with their beloved father and grandfather.

They spent their last moments together on Christmas Day.

“It feels like you’ve lost one last chance to talk; one last time to enjoy each other’s company,” Giles says.

Giles’ 13-year-old son, Nolan, was likely infected with the virus while playing hockey, and probably spread it to his dad. The pair both had nasty symptoms after a small family Christmas gathering.

The two tested negative on rapid tests on Christmas Day. They were informed later that day that one of Nolan’s teammates and someone from a training facility he attends had both tested positive.

Nolan got a positive rapid-test result Dec. 27, followed by his father two days later. Nolan’s PCR test confirmed the results after a three-hour wait at a drive-thru site.

In addition to the typical cold and flu-type symptoms, Kevin has had to deal with brain fog.

“Any time I had to think or make a decision, or even trying to read and interpret and understand something, my brain wouldn’t make the right connections. Even simple things like responding to an email felt overwhelmingly difficult,” he says, adding he has had to take a break from working as an independent software consultant for the past three weeks.

“My job is mostly thinking, so it knocked me out.”

”Any time I had to think or make a decision, or even trying to read and interpret and understand something, my brain wouldn’t make the right connections.”–Kevin Giles

The worst part, however, was lost family time.

Giles’ father, Michael, who had a heart condition, died suddenly Jan. 9.

“It just feels like a missed opportunity to spend some time together that we’ll never get again,” he says.

This week, Kevin was planning a viewing at a funeral home under Omicron restrictions while still grappling with brain fog, and not being able to taste food or breathe adequately to exercise again.

“This is a serious disease. I hear a lot of things: it’s not so bad, that it’s minor and a lot of people will get over it — but this does have a huge impact,” he says.

dylan.robertson@freepress.mb.ca | danielle.dasilva@freepress.mb.ca | maggie.macintosh@freepress.mb.ca

Maggie Macintosh reports on education for the Winnipeg Free Press. Funding for the Free Press education reporter comes from the Government of Canada through the Local Journalism Initiative.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, January 14, 2022 7:17 PM CST: Minor fix to grammar in second vignette.

Updated on Saturday, January 15, 2022 9:16 AM CST: Tweaks webhed