Picture this Canadian Paintings tunes out the noise of social media with its contemplative feed of visual art

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/01/2022 (1425 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Susanne Visser was on Twitter last week, scrolling past morbid statistics, silly arguments and scathing hot takes, when she came across something that stood out starkly from the endless, depressing slog: a painting by her great-grandfather.

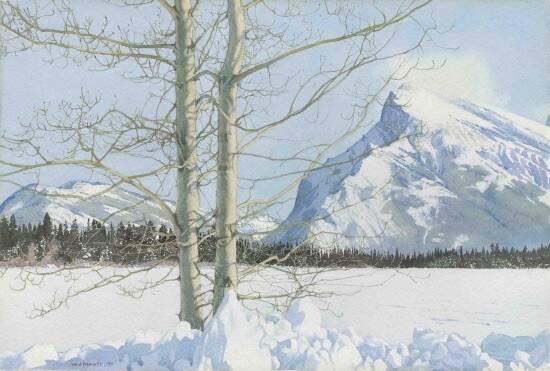

Walter J. Phillips’ wintry portrait of Alberta’s Mount Rundle was painted in 1950, a decade after the British-born artist left his adopted home of Winnipeg for the rocky terrains of Banff. In his new habitat, Phillips created peaceful depictions of the natural beauty around him, while teaching at both Calgary’s Institute of Technology and Art and the Banff School of Fine Arts.

Born in 1884, he died in 1963. So how was it that on Jan. 8, 2022, at 11:18 p.m., Phillips’ great-granddaughter — and his great-great granddaughter, who was quarantining with her mother after they had tested positive for COVID-19 — was greeted by his subtle brushstrokes through the glowing screen of her iPhone?

Visser is one of the 106,000 followers of Canadian Paintings, a Twitter account that shares exactly and only what its name promises. Every day, the account posts several pieces of art made by Canadian painters. The only content of any of its posts is the title of the piece, the year it was made, the artist who made it, and below that information, the piece of art itself.

There is no criticism, no opinion, no commentary, no statements about the particular artists’ fame or renown; there are only paintings. The curator understands that the purest reaction to art relies only on what is seen, heard and felt, not on theory or context or expertise. That perhaps, it’s best to let the art first speak for itself.

And it does, in a way that can often lose its meaning when translated into English or Spanish or French, or academic lingo, or a newspaper article. Pat Bovey, a Canadian senator, art historian, and the former director and curator of the Winnipeg Art Gallery, says the account speaks volumes in a timeless, universally understood tongue: the international language of visual art.

“In many cases, our lives are being defined by what we can’t do,” she says. “But what this does is it shows us what we can do. It opens our minds and opens our hearts and opens our pasts, which open up our present. And it gives us a window into what our futures could be. And I think that’s very restorative.

“It doesn’t matter what our background is, and it doesn’t matter if you’re decades younger than me. These pieces have a very real effect on me, and they are having a very real effect on others,” she says. “And you may look at them differently than I do, and see different things. That is what makes this art so rich.”

In a social media world that often has more in common with a cesspool than a mineral bath, that richness is being savoured by thousands with every single post.

“It’s a lovely account to follow, especially when you’re bogged down by the news,” says Visser, who says she and her daughter have both recovered. “But I find no matter my mood, I love Canadian Paintings. Whoever is running it is doing a fantastic job, and I admire them.

“How many tweeters do I admire? Not very many.”

The Canadian Paintings account was created in December 2018, but only recently, since the start of the pandemic, has its following expanded to the level of a celebrity or a rising social media influencer.

But unlike most celebrities, and the majority of influencers, who also tend to use the word “curate” in referring to their social media, there is no profit motivation within the account, nor is there any showmanship.

In fact, the person who runs Canadian Paintings is a Canadian elementary school teacher and PhD candidate who finds the artwork during breaks from their grad school work. They didn’t even want to share their name, lest it distract from the account’s purpose. It’s a pure pursuit that has flourished at a chaotic moment.

“All the news in the world can leave a person with a heavy heart,” tweeted Leanne Chesnutt, above a painting by British Columbia artist Monica Morrill, entitled Winter Adventure. “This account is the perfect antidote.”

“It’s been really exciting following Canadian Paintings and seeing my work pop up on their account,” says Morrill. “I feel very fortunate to have my artwork in the company of so many well-known and talented Canadian artists and am so grateful for the opportunity to have my work shared so widely. And all of the positive feedback has been amazing and very encouraging.”

Scrolling through the account makes one realize that what makes a painting Canadian is often about more than who painted it and where; the paintings shared all in some way depict a visual story in the international visual language Bovey describes, but they do so using regional and national dialects.

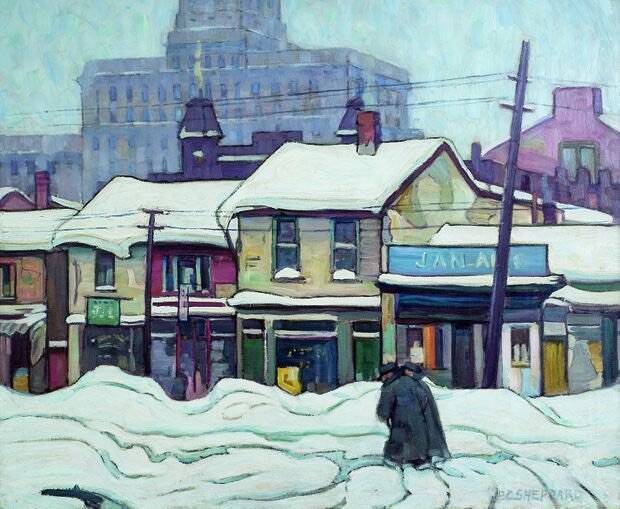

Elizabeth Street, Toronto, the Peter Sheppard painting from 1930 shared on Jan. 7, depicts a hunched couple in winter garb attempting to cross the street, covered in snow that reaches to their kneecaps. That painting is set in Toronto, before the Great Depression, but is it not an experience all Canadians understand?

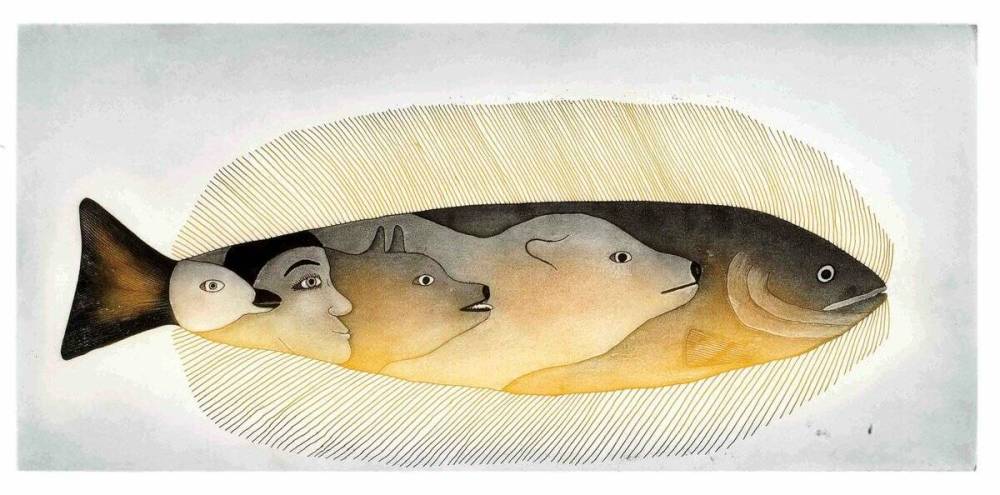

There is Cree art, such as Jerry Whitehead’s Wake Up and Inuit art, such as Mialia Jaw’s Ancient Vision, that build on ancient cultural traditions to tell stories that were told thousands of years before this place was ever called Canada. There’s the Ukrainian Christmas Eve by William Kurelek, and the Trans-Canada Highway by Peter McConville. There’s Mary Pratt’s painting of an aluminum-foil-wrapped Christmas turkey.

These are all national paintings, each in their own way, and they invite you to get lost in the worlds they evoke.

But why is this account, and the type of distraction it offers in particular, so popular? Why now are people seeking out visual art like this when so much is going on? Bovey thinks it’s because art can give people the chance to believe and imagine, and the account’s posts give followers the opportunity to have something to which they can look forward. Someone recently told her, she says, that “art saves lives, because it connects to the inner soul that drives us.”

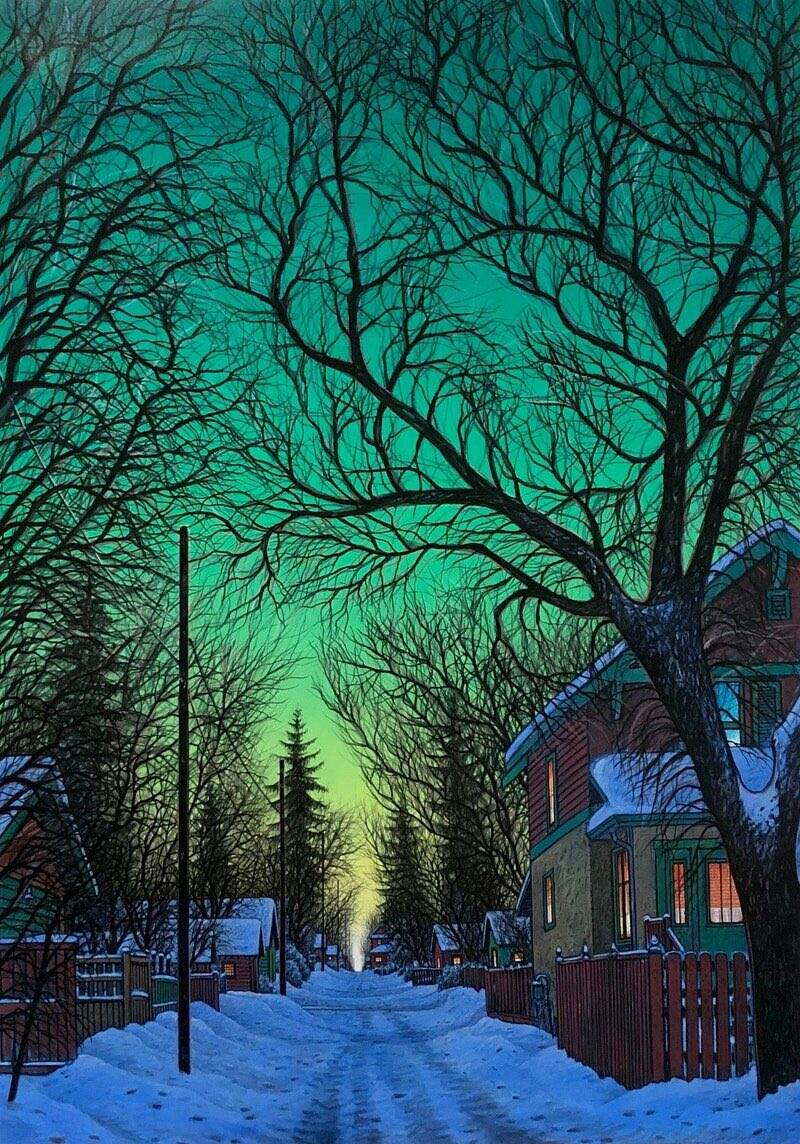

Perhaps that explains why Prairie artist Wilf Perreault’s 2019 painting, There Is Light on the Horizon, posted on New Year’s Eve, was shared more than 3,000 times. The painting shows a well-trod, snowy back lane, lined with trees bereft of leaves and underneath a green-yellow sky, the alley narrowing until it finally arrives at a glowing, vanishing point of light. The light seems far off, but it’s only half a block away. Who knows what the light on the horizon is? Maybe it’s hope. Maybe it’s just light.

“God,” tweeted Frances Mote at the painting. “I hope so!”

ben.waldman@winnipegfreepress.com

Ben Waldman covers a little bit of everything for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.