Arresting numbers Experts argue there are better, cheaper ways to reduce crime

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 27/08/2021 (1656 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

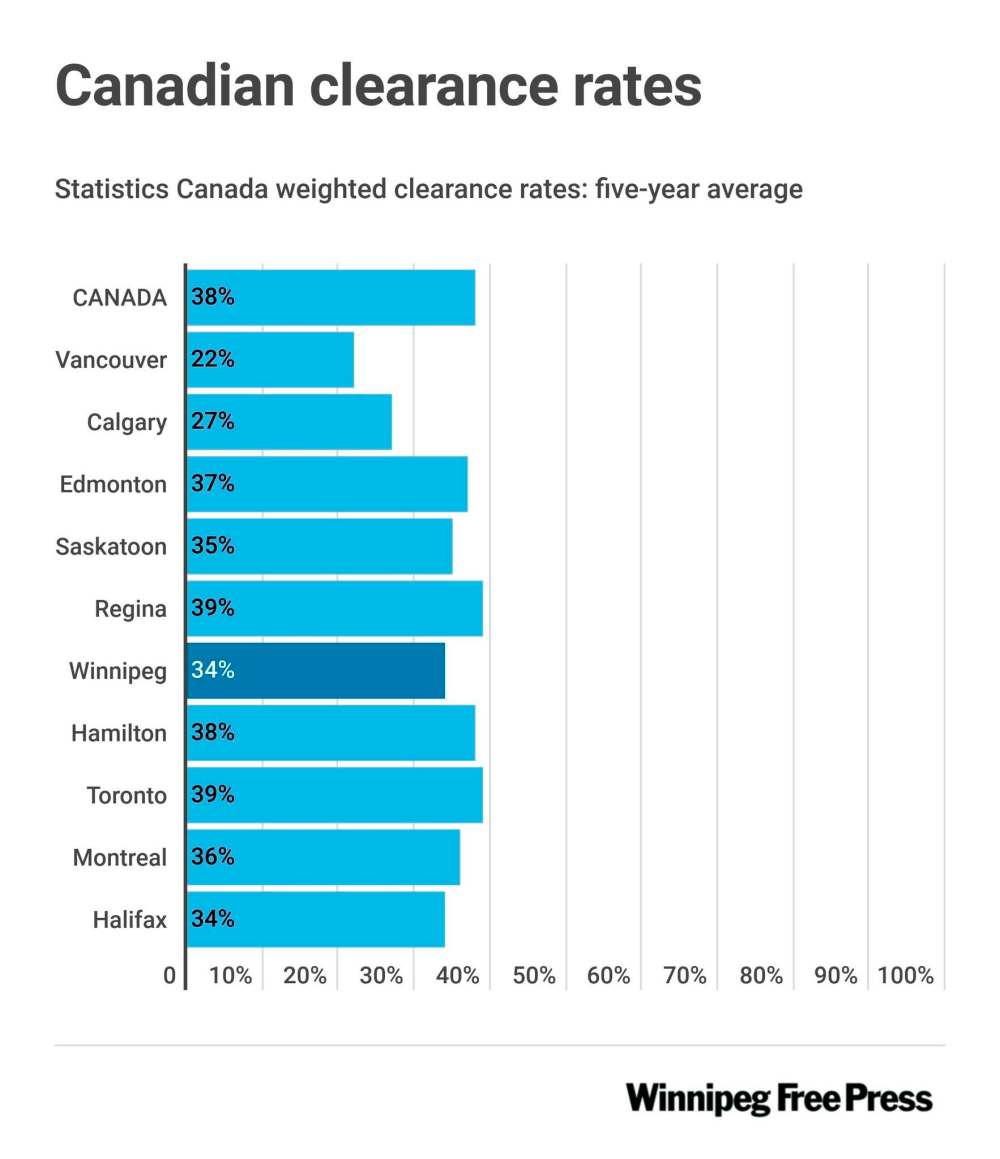

Winnipeg is one of the top spenders on policing in the country — earmarking 27 per cent of its annual budget for law enforcement costs — yet clearance rates in the Manitoba capital trail behind those seen in many other Canadian cities.

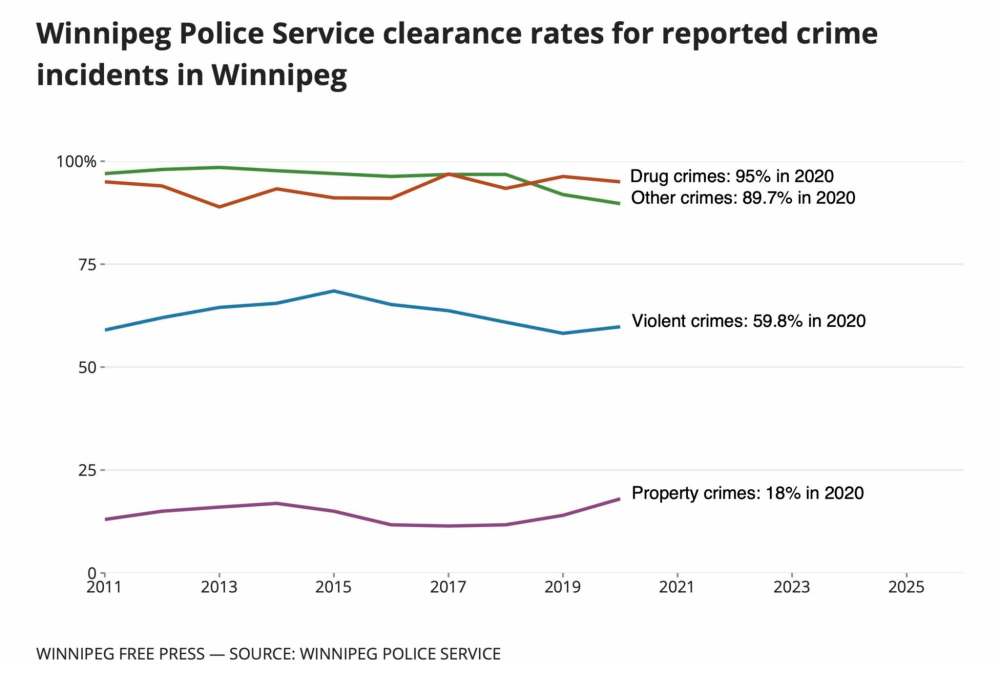

Among the cases reported to police, people who commit violent crimes in Winnipeg have roughly 50-50 odds on finding themselves in handcuffs.

Over the past five years, the police clearance rate for violent crime in the city is 51 per cent, according to data recently released by Statistics Canada. For non-violent crimes, the five-year clearance rate is 24 per cent.

Winnipeg’s weighted clearance rate for all crimes — a datapoint calculated by Statistics Canada by factoring in a jurisdiction’s crime-severity index — is 34 per cent, which comes in four percentage points lower than the national average.

Among all 10 major cities the Free Press analyzed clearance rates for, Winnipeg tied for third-last, trailing behind only Vancouver and Calgary at 22 per cent and 27 per cent, respectively.

A spokeswoman for the Winnipeg Police Service referred the Free Press to the agency’s 2020 annual report for additional information about clearance rates.

According to the report, 15 per cent of violent crimes in Winnipeg “cannot be solved because the victim will not identify the suspect,” while 55 per cent of property crimes “do not have enough evidence to solve the event.”

But such police-reported data provides only a snapshot into the rate of social transgression and criminality happening in any given community.

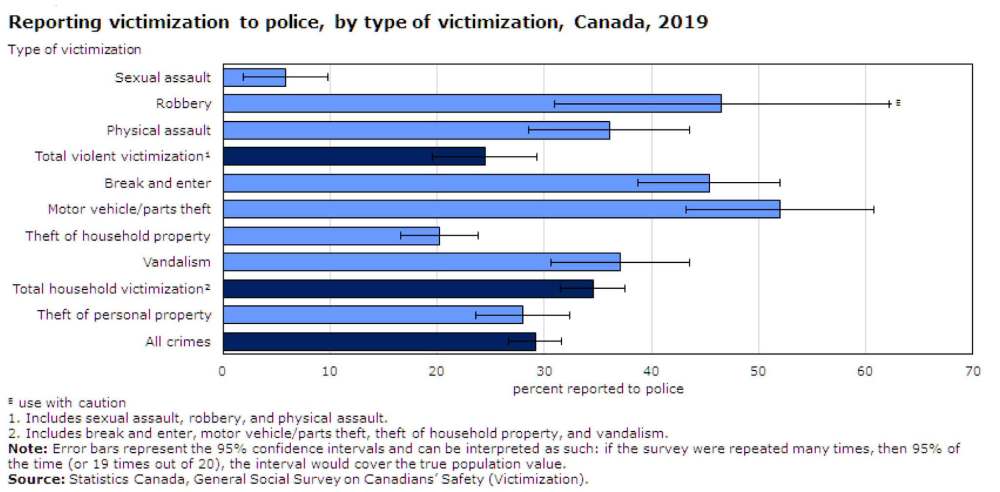

On Wednesday, Statistics Canada released its latest report on criminal victimization in Canada, which found that only 29 per cent of “incidents of victimization” were reported to the police in 2019.

That means less than a third of crimes are being reported to police, and even when they are, only about one-third of them in Winnipeg lead to criminal charges — with only a subset of those cases later leading to convictions.

Among all crimes, sexual assault is the least likely to be reported to police, with only six per cent of incidents in 2019 leading to police reports.

Irvin Waller, a criminologist, victims’ advocate and professor emeritus at the University of Ottawa, said those numbers should be concerning for law enforcement and public policy-makers.

Police, fire and paramedic services swallow nearly half of Winnipeg's operating budget, leaving little for other civic departments

Posted:

It’s there in the orange dots of death that spot the bark of trees. In the cratered back alleys and side streets. In the homeless encampments lining the banks of the rivers.

“That is not a very good indicator of public confidence in policing,” Waller said.

Data culled from successive WPS annual reports shows the number of sworn police officers in the city has been declining over the past five years while department funding increased.

There was a four per cent decline in sworn police officers in Winnipeg during the past five years — falling from 1,421 in 2016 to 1,356 in 2020.

At the same time, efforts to diversify the department appear to have hit a roadblock. The percentage of the overall police force that is female, Indigenous or a visible minority has remained stagnant during that period.

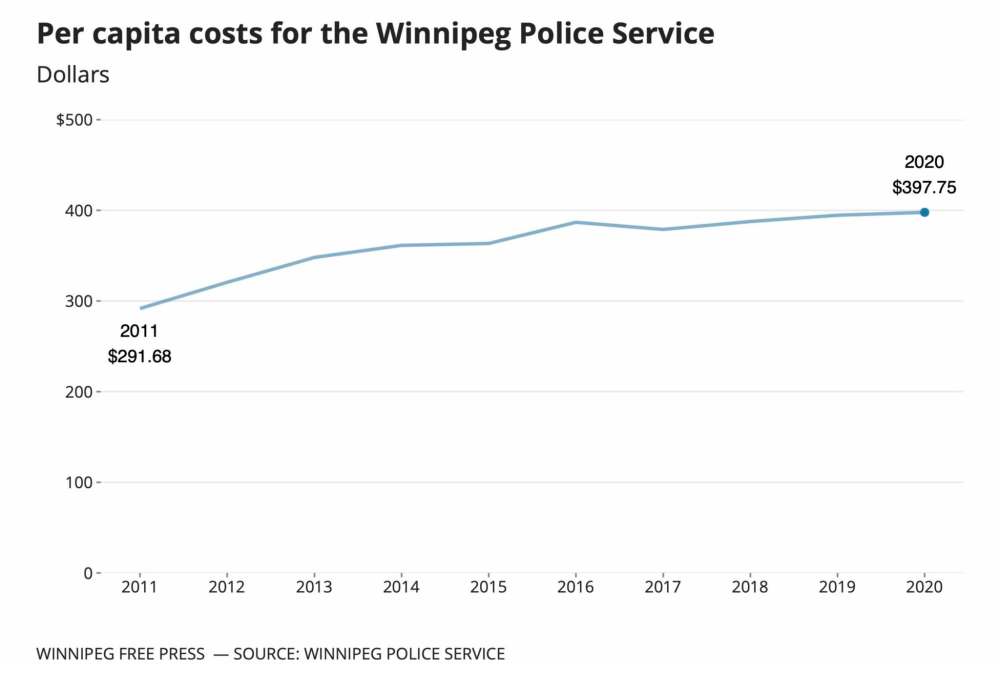

Meanwhile, the per capita costs of policing in Winnipeg have risen, consistently ranking higher than the national average. In 2019, per capita costs were $394 in Winnipeg and $317 nationally.

The percentage of policing costs that go towards salaries and benefits are also higher here. Across Canada, 81 per cent of policing costs go towards paycheques, compared to 85 per cent in Winnipeg.

The figure was even lower — 77 per cent — among Ontario police departments.

Funding increases to the WPS in recent years have largely been eaten up by labour costs. The number of WPS employees making between $100,000 and $150,000 rose by 16 per cent during the past five years, jumping from 724 to 843.

During the same period, the number of police department staff making more than $150,000 rose from 14 to 52.

As of last year, 895 WPS employees were making $100,000 or more annually. An additional 486 employees earned between $75,000 and $99,999, making them eligible for inclusion on the City of Winnipeg’s annual salary disclosure.

The average salary for a Winnipeg police officer now sits at $122,000.

Defunding police uphill battle

Efforts to reduce funding to the Edmonton Police Service illustrate the uphill battle “defund” activists and advocates face in other Canadian cities.

In the aftermath of the death of George Floyd — a Black man murdered by ex-Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin on May 25, 2020 — efforts to defund or abolish the police picked up steam across the world.

In Edmonton, city council voted that summer to reduce the budget of the EPS by $11 million over the course of two years — instead reallocating that money to supportive housing and other community services.

It was one of many progressive changes approved by city council that summer. All told, Edmonton city council approved 20 initiatives aimed at reforming policing in the community.

Efforts to reduce funding to the Edmonton Police Service illustrate the uphill battle “defund” activists and advocates face in other Canadian cities.

In the aftermath of the death of George Floyd — a Black man murdered by ex-Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin on May 25, 2020 — efforts to defund or abolish the police picked up steam across the world.

In Edmonton, city council voted that summer to reduce the budget of the EPS by $11 million over the course of two years — instead reallocating that money to supportive housing and other community services.

It was one of many progressive changes approved by city council that summer. All told, Edmonton city council approved 20 initiatives aimed at reforming policing in the community.

City council also expressed support for the idea that all public complaints about police should be handled by the Alberta Serious Incident Response Team, their provincial counterpart to the Independent Investigation Unit of Manitoba.

The Edmonton Public School Division also suspended its “school resource officer” program — in which police officers are assigned to various schools — for the upcoming academic year, saying the future of the program was under review.

Combined funding for police, community services, attractions, public transit and the fire department account for 51.8 per cent of Edmonton’s municipal budget.

Meanwhile, in Winnipeg, funding for emergency services alone (police, fire and paramedic services) accounts for 45 per cent of the city’s budget.

But those efforts to reduce funding to the EPS came under threat in September, when Alberta Justice Minister Kaycee Madu warned the municipality that if it gave into activist demands to “defund the police,” the province would respond.

Madu told Edmonton Mayor Don Iveson in an open letter that if funding to the EPS was reduced, the province would look for ways to bypass the municipality and allocate fund directly to the police.

In a subsequent interview with the National Post, Madu also hinted that if Edmonton moved to reduce police funding, the province would consider it a sign that the municipality did not need grant funding specifically designated for policing costs.

In a past interview with the Free Press, Brian Kelcey, who served as a special adviser to former mayor Sam Katz, said circumstances such as Edmonton’s and a similar one in British Columbia point to the important role provincial legislation plays with police funding.

Any conversation about reallocating funding from municipal police services must also take the provincial government into account, Kelcey said, because the province has powers to override funding decisions that come from city councils, in certain cases.

— Ryan Thorpe

While reforms to law enforcement could help lower criminality in limited ways, Waller said public policy-makers need to focus on tackling the things that lead to crime in the first place, since policing is a reactive strategy downstream of root causes.

“There are some things you can do with policing, but these are quite limited and expensive — particularly in Canada, where salaries have gone up so quickly…. If you don’t tackle the causes, you’re going to end up spending on reactive responses,” Waller said.

“The first thing we actually need is a plan. That’s what a city, which actually wants to reduce violence, starts with.”

A proactive approach to reducing crime in Winnipeg would require funding from all three levels of government, Waller said, as well as an ability to move beyond disproven notions that simply increasing the number of police officers on the street will lower crime rates.

“Too many cities do not have any strategic plan for how they are going to reduce street violence and violence against women…. If they did, they would be looking at what are the cost-effective ways and sustainable ways to reduce these things,” he said.

“We actually know a lot — and it’s very solid — about how to reduce street violence…. It’s very clear to anyone who takes a few minutes to look into the research what a city like Winnipeg should be doing.”

ryan.thorpe@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @rk_thorpe

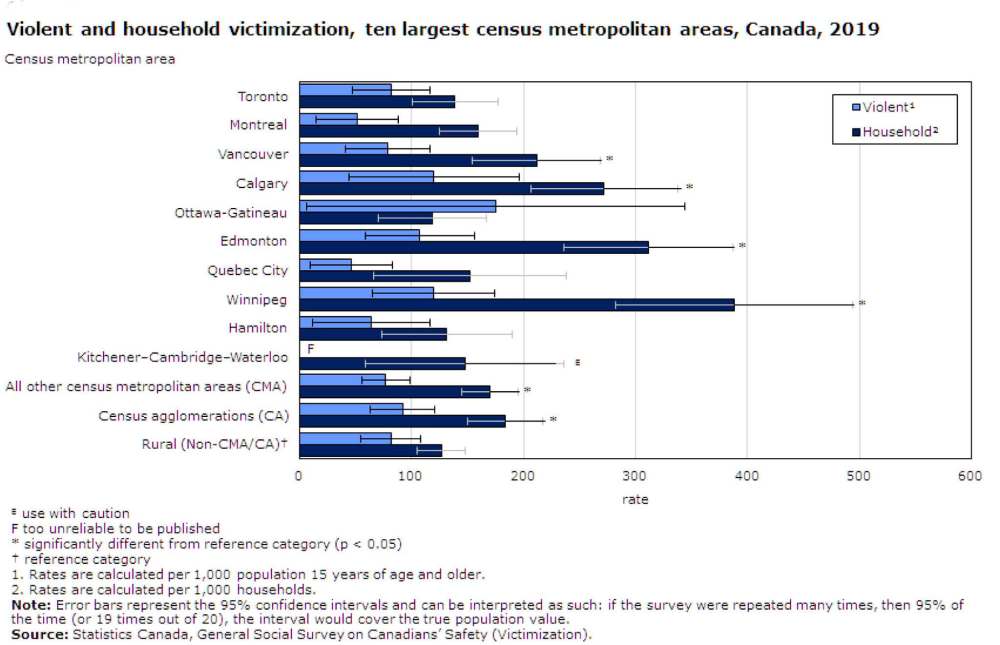

Criminal victimization in Canada, 2019