The high price of protection: Safety first, everything else last Police, fire and paramedic services swallow nearly half of Winnipeg's operating budget, leaving little for other civic departments; critics say runaway labour costs are to blame and don't make the city any safer

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 20/08/2021 (1572 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It’s there in the orange dots of death that spot the bark of trees. In the cratered back alleys and side streets. In the homeless encampments lining the banks of the rivers.

It’s there in the trash and used needles scattered in city parks. In the signs of decay and distress everywhere you look. And in the sounds of emergency sirens ripping through the air day and night.

It’s a mounting tension that’s the result of decades of two opposing forces — spending and neglect — and it’s the culmination of countless, conscious decisions from civic leaders coming to a head.

The problem sounds simple enough: limit the growth of the two largest municipal departments and leave enough resources to properly fund other services citizens want and need.

But in Winnipeg, it is anything but simple. It’s also not working.

Funding for emergency services in this city has been growing at an alarming, unsustainable pace for the past two decades — far outstripping the rate of inflation and cannibalizing the resources needed to support other civic departments.

Massive gains by the Winnipeg Police Service and the Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service have directly undermined the city’s ability to fund community development and other important initiatives.

A Free Press analysis of 10 years of City of Winnipeg operating budgets, as well as successive collective bargaining agreements, has identified the culprit behind skyrocketing emergency services budgets: runaway labour costs.

That is, in part, due to the strength of the Winnipeg Police Association and the United Fire Fighters of Winnipeg — two powerful public-sector unions that have consistently secured generous compensation packages for their members.

There has been no shortage of politicians and policy advisers, advocates and academics who have pointed to the rising costs in recent years and sounded alarm bells.

Nevertheless, the costs continue to rise.

In the aftermath of the death of George Floyd, a Black man murdered by ex-Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, there has been a growing worldwide movement calling for the defunding of law enforcement agencies.

That movement has arrived in Winnipeg, with increasingly visible and vocal activist groups organizing demonstrations, launching petitions and mobilizing politically in an effort to defund the WPS.

But less attention has been paid to what defunding would look like in practice, and what legal roadblocks exist — through the existence of collective bargaining contracts — that stand in the way.

● ● ●

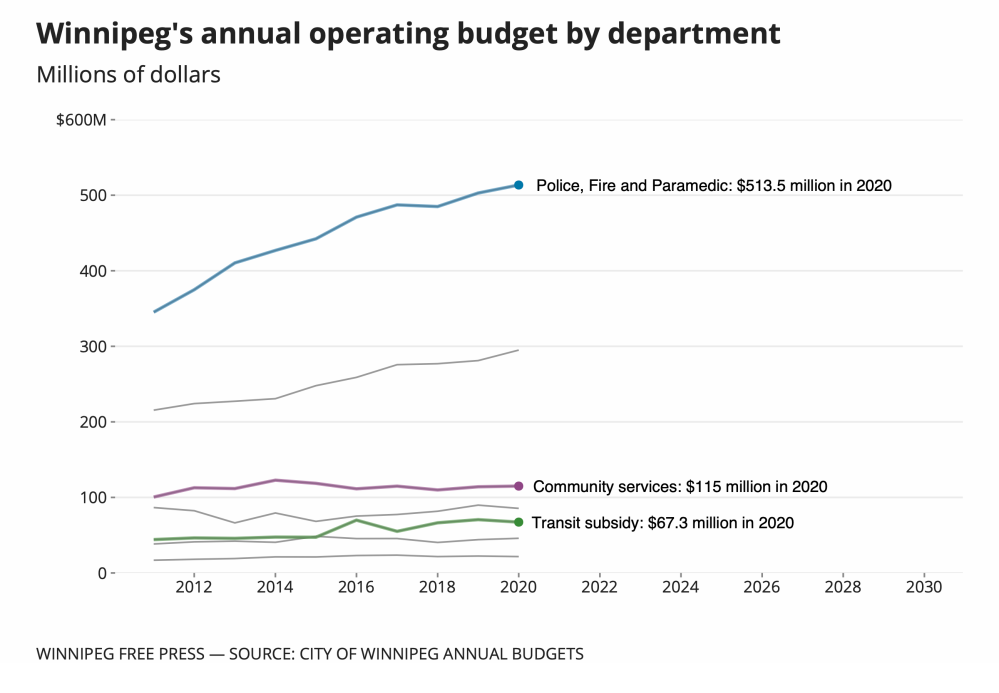

Together, the annual operating budgets for the WPS and the WFPS rose by 48.8 per cent from 2011 to 2020, an increase of $168.3 million. The increase came during a period in which the number of fires in the city dropped precipitously and crime rates were declining from their peak in the late 1990s.

The police budget rose from $202.4 million in 2011 to $304.1 million in 2020, or 50.4 per cent. The WFPS budget rose from $143 million to $209.4 million, or 46.4 per cent.

During the same time period, the city’s overall budget increased by 35 per cent, from $847.3 million to $1.14 billion.

Funding for the two departments now accounts for 45 per cent of the city’s total tax-supported operating budget. It’s a situation critics say is untenable and directly undercuts the municipality’s ability to fund other services.

“If you’re wondering why the city hasn’t kept up with issues with the tree canopy or your local pools are crumbling or roads still aren’t up to shape, this isn’t the only reason… but it’s a significant driver,” said Brian Kelcey, a special adviser to former mayor Sam Katz.

“So much money is going to steady increases over inflation to these departments, and there aren’t many tools in the city’s arsenal to try to contain them.”

The result is that Winnipeg has become one of the highest spenders on emergency services in Canada. Only two other municipalities spend more on policing: Surrey, B.C. and Longueil, Que.

While Winnipeg spends 27 per cent of its annual budget on police services, Edmonton, Montreal and Toronto spend just 15 per cent, 11 per cent and nine per cent, respectively.

Salaries and benefits account for 85 per cent of the total WPS and WFPS budgets.

That means the spike in emergency services costs in Winnipeg is not going to fund improved service delivery for citizens, but instead go into the bank accounts of already well-compensated department employees.

During the pandemic alone, WPS employees have received three across-the-board raises: a one per cent pay bump in June 2020, 1.5 per cent in December 2020 and one per cent in June 2021.

Come Dec. 31, they will receive another 1.5 per cent raise.

According to the city’s latest annual compensation disclosure, the average salary for a police officer in Winnipeg is now $122,277, and for a WFPS employee, it’s $118,207.

Meanwhile, according to the latest census data available, which was published in 2016, the average annual income in Winnipeg is $44,916 — although that figure is likely to have increased in the years since.

Nearly half of the city’s top-50 earners in 2020 were police officers (24 of 50), with WPS Chief Danny Smyth taking in more than any other municipal employee: $291,834.

John Lane, who retired earlier this week as WFPS chief, was paid $226,825 in 2020.

All told, there were 1,381 WPS employees and 1,108 WFPS employees on the city’s 2020 annual compensation disclosure agreement, which charts the salaries of all municipal workers making $75,000 and up.

Unless municipal politicians and city negotiators are able to rein in labour costs, funding for emergency services in Winnipeg will continue to spiral out of control in the years to come.

And the people who will foot the bill will be the same people who always foot the bill: Winnipeg taxpayers.

“This is a lot of money. And it’s a lot of money while a lot of other folks in society are having a tough time. The taxpayers’ ability to pay isn’t being taken into account,” said Todd MacKay, prairie director of the Canadian Taxpayers Federation.

“At this point, it just feels like raises are being rubber-stamped, and it can’t go on forever. It’s not responsible and it’s not sustainable… I think there are some really pointed questions that need to be answered here.”

● ● ●

On the eve of the City of Winnipeg’s 2016 budget vote, political points were being scored in the press, fights over the future of police resources were heating up and the possibility of layoffs loomed.

The Winnipeg Police Board — the arms-length, civilian-led entity mandated to provide oversight of the WPS — was warning of a budget shortfall ranging from $2.4 million to $3.5 million.

City council had committed to a generous annual funding increase for the WPS, but Winnipeg Police Association President Maurice Sabourin claimed it wasn’t enough. Calls for service were on the rise, he said, so funding must be, too.

Unless more funding was secured, then-police chief Devon Clunis warned the WPS would lay off scores of cadets and new recruits. Even so, he admitted such funding increases to police were not sustainable in the long term.

Police board chairman Coun. Scott Gillingham, who also served on the finance committee, and Mayor Brian Bowman, then early into his first term, both said the same thing in statements to the press.

The situation with the Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service wasn’t much better: that year, the fire-paramedic budget jumped by an additional $12 million, up to $190.3 million.

In just five years, the WPS and WFPS budgets rose by $78.5 million and $47.3 million — average annual increases of $15.7 million and $9.46 million, respectively.

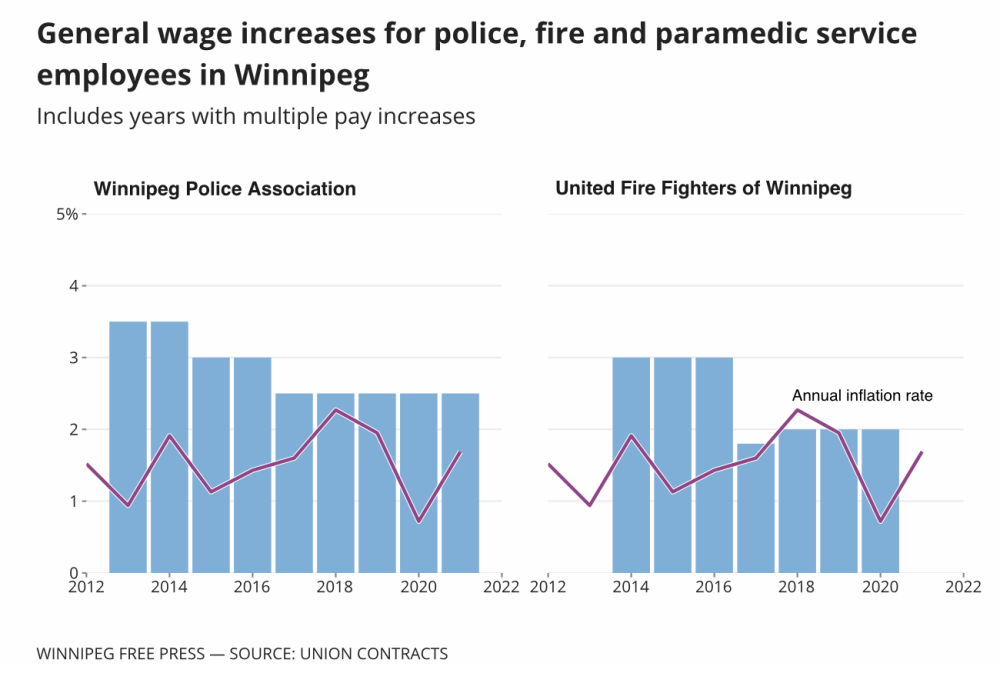

And while pay bumps for police and firefighters have slowed somewhat since, they continue to rise well above the rate of inflation.

Police received a 3.5 per cent raise in both 2013 and 2014, a three per cent raise in both 2015 and 2016 and a 2.5 per cent raise every year since.

Firefighters received a three per cent raise in 2014, 2015 and 2016, a 1.8 per cent raise in 2017 and a two per cent raise every year since.

In an interview with the Free Press, Gillingham said there have been “concerted efforts” at city hall to slow the annual growth of emergency services. While he feels some progress has been made, he admits “the battle has not been won.”

“It will continue to be a challenge…. Approximately 85 per cent of those budgets are salaries and benefits. Those are negotiated through collective bargaining and those are collective agreements,” he said.

“One of the means of controlling the rate of growth is through the collective agreements. We’ve endeavoured to avoid arbitration wherever possible and to reach an agreement. That takes two sides.”

According to Kelcey, the deck is stacked against the municipality in the collective-bargaining process to such an extent that it’s “almost impossible” for council to “contain these costs.”

“The key word for me is bargain. Having a healthy recognition that there is a public interest in restraining costs and growth, just as there is a public interest in making sure people are well-compensated,” he said.

“You want to find equilibrium, but right now, the system is not designed to find equilibrium.”

One of the issues, according to Kelcey, is the threat of arbitration hangs over the head of city negotiators, who know it is more favourable to unions than to taxpayers.

“Even if a contract doesn’t go to arbitration — the mayor’s cabinet, city council and the city’s negotiators — they all know that it could. This is an easy button that can be pushed that can go really bad for the city budget,” he said.

“This drives a reluctance to push and really bargain… because arbitrators don’t have to take into account any city fiscal objectives.”

That sentiment was echoed by MacKay, who said there are serious structural issues that hamper the ability of municipalities to rein in emergency-services costs.

The threat of arbitration generally increases the municipality’s initial offer at the bargaining table, MacKay said, which then gets taken as the “starting point” by the arbitrator if contract negotiations break down.

“The arbitrator is going to look at what other comparable government employees got in other jurisdictions and provide a ruling. What usually happens is each arbitrator across the country bumps things up a little bit based on what the other guy got,” he said.

“It has a ratchet effect, and it keeps going up everywhere, and it’s a huge problem, because nowhere in the equation is the taxpayers’ ability to pay considered.”

And while MacKay points to structural factors and politicians who don’t want to make hard choices as issues that must be reckoned with, he also said union leadership bears responsibility.

“Their goal should not only be to get a good deal for their members. Their goal also needs to be to get a sustainable structure that will make sense in the long term. If they try to fleece the sheet too hard, it’s going to be a problem,” he said.

“Their members are going to end up paying for it in the long run…. If you keep kicking the can down the road, you’re going to have much tougher news to deliver when the situation reaches a breaking point.”

In Winnipeg, the unions representing the vast majority of emergency-services workers — the WPA and the United Fire Fighters of Winnipeg — are two of the most powerful public-sector unions in the city.

And both have repeatedly shown their willingness to throw their weight around, both at the bargaining table and in the political arena.

● ● ●

In the leadup to the 2018 municipal election, the Winnipeg Police Association launched its most provocative political effort in recent memory: an attack ad on incumbent Mayor Brian Bowman.

The 30-second TV spot began with the sound of a window shattering as a teenage girl scurried into a closet. She dialed 911 as a presumed home intruder closed in on her. The phone rang and rang and rang — no one picked up.

An automated message told the girl that an operator would be with her soon. Then a shadow fell upon her face as she looked up in horror. The ad ended with an ominous voiceover: “Why is Winnipeg 911 not fully staffed? Ask Mayor Bowman.”

The implication was clear: unless the police service received more funding, people in Winnipeg would suffer. Bowman and the municipal government would have blood on their hands; more police funding was the only thing holding back violence and chaos.

The ad was quickly denounced as fear-mongering by critics, but the WPA’s Sabourin stood by the decision to run it, claiming it was needed to call attention to “inadequate police budgets.”

When reached for comment for this story, Sabourin continued to stress the underfunding theme in a written statement sent to the Free Press.

“WPA members work tirelessly every single day to serve and protect the citizens of Winnipeg. We have been consistent in our view that the WPS budget should be based on the demand for services, not tied to the rate of inflation,” he wrote.

“That demand remains extraordinarily high and therefore requires proper funding in order for our members to carry out their duties.”

“It has a ratchet effect, and it keeps going up everywhere, and it’s a huge a problem, because nowhere in the equation is the taxpayers’ ability to pay considered.” — Todd MacKay, prairie director of the Canadian Taxpayers Federation

It’s similar to the argument Sabourin put forth as the 2018 municipal election got underway. Speaking to the press, he claimed Bowman was asking police to do “twice as much with the same number of resources.”

The union leader explicitly called for cuts in order to funnel more money to the police, suggesting the cancelling of the proposed reopening of Portage and Main, the scrapping of the bus rapid-transit system and a deduction in active-transportation infrastructure.

Despite Sabourin’s claims that police resources were stagnant, in the five years leading up to his comments, the police budget had grown by $49 million — rising from 21.2 per cent of the city’s overall operating budget to 26.9 per cent.

The following year, after the WPS received an additional $10 million in funding, he penned a letter to the Free Press, claiming that “more police resources are urgently needed to protect the public from a crime problem that is getting worse.”

Kevin Walby, a criminologist and associate professor at the University of Winnipeg who recently co-authored a paper on the political communications of police unions, said those anecdotes are telling.

They highlight the ways in which the WPA has consistently pushed for additional resources for its members without considering — or, seemingly, caring about — the impact funding hikes have on taxpayers and the community at large.

Walby and his co-author, Jamie Duncan of the University of Toronto, argue the WPA strives to achieve its goals by “amplifying a sense of fear,” and conflating the interests of the police with the interests of the public.

“The (WPA) is all too willing to hold the city over a barrel to get whatever it wants…. It’s demonstrated, time and time again over multiple bargaining sessions, it doesn’t really care what is in the public interest,” Walby said.

“It’s what’s called, in sociological terms, a ‘greedy institution.’ It collects whatever resources it can, regardless of the cost for other members of society.… It’s not purely economic, either. It’s also about assembling social and political capital.”

“I don’t think it’s possible to have healthy, well-funded communities when you’re spending almost half of your budget on purely reactionary services.” — Kevin Walby, criminologist and associate professor at the University of Winnipeg

Despite the claims of law enforcement, union leaders and criminal-justice policy-makers to the contrary, every academic who spoke to the Free Press said there is no relationship between police funding and crime rates.

As Christian Leuprecht, a professor at both the Royal Military College of Canada and Queen’s University, put it: “How much money we put into policing has no impact on crime — every criminologist, regardless of political stripe, will tell you that.”

But that hasn’t stopped the WPA from trying to stoke the public’s fears; unless its demands are met there will be more violence in the streets.

The union has also pushed for concessions from city negotiators that better protect members accused of misconduct. As a result of the collective agreement, disciplinary hearings for Winnipeg police officers are not subject to public scrutiny.

As far back as the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry of 1988 and through to the Taman Inquiry of 2008, the WPA also has a documented pattern of attempting to obstruct probes into police killings.

And while increased protections for workers are things every union fights for, the dynamics at play are different when the workers in question are armed agents of the state with a monopoly on the legitimate use of force in society.

In addition, the WPA successfully petitioned the city several years ago to remove the names of police officers from the annual salary compensation disclosure document — a perk enjoyed by no other civic department and seen in no other jurisdiction.

Walby said the status quo not only has financial repercussions for the city and its taxpayers, but also a human cost.

“I don’t think it’s possible to have healthy, well-funded communities when you’re spending almost half of your budget on purely reactionary services,” he said.

“That’s the crux of the matter. And you don’t need a PhD to understand that.”

Like the WPA, the UFFW has long been active in provincial and municipal politics, door-knocking for candidates in elections, funnelling money into advertising campaigns and developing back-channel relationships with politicians.

Led by longtime president Alex Forrest, the UFFW has also developed a reputation for litigiousness, and a tendency to circle the wagons when controversy strikes.

Last April, Jennifer Setlack, a former paramedic turned academic who earned two master’s degrees while working for the city, published a thesis entitled “Winnipeg’s Reliance on Emergency Services and the Firefighting Exception.”

“Winnipeg has created a crisis of its own making, and then we continue to make the same mistakes. The 2020 budget made significant cuts to community health infrastructure. We’re just going to keep going down the same path.” — Jennifer Setlack, a former paramedic turned academic

Setlack argues that decades of divestment in community health and welfare have created a gap in service that only the WPS and WFPS — which are purely reactionary services incapable of addressing root causes of transgression and disorder — are able to meet.

This results in a cycle of “increased demand for police and paramedic services, followed by frequent funding increases to these departments,” according to her thesis.

“Winnipeg has created a crisis of its own making, and then we continue to make the same mistakes. The 2020 budget made significant cuts to community health infrastructure. We’re just going to keep going down the same path,” Setlack said.

While there are benefits to public-sector unions, she argues — much like Walby with the WPA — that the UFFW has negotiated itself into such a destructive position that there is now an “inverse relationship” between its interests and the public’s.

“Is what we’re doing working? What we’re doing now is that emergency services costs just keep ballooning year after year.… We can either keep doing what we’re doing, keep going down the same road, or we can find another way,” she said.

“I don’t think we really have an option.”

● ● ●

There is an appetite for a reduction in police funding in Winnipeg.

Five months after Floyd’s murder in Minneapolis, the polling company Angus Reid published the results of a cross-country survey into public perception of police in Canada.

Among all major Canadian cities, Winnipeg trailed behind only Toronto when it comes to support for the partial or complete defunding of police.

In Winnipeg, 36 per cent of respondents said they want police funding decreased, 30 per cent want it to remain where it is, and 20 per cent want it increased.

In addition, 36 per cent of Winnipeggers said the way police treat racialized communities is a “serious problem,” with an additional 29 per cent saying it is “sometimes a problem.”

Earlier that year, a petition started by a local activist group — which explicitly called for the defunding of the WPS — garnered more than 120,000 signatures in support.

Walby said that research from criminologists and sociologists has consistently shown that increased policing does not reduce crime. In fact, he argues, it can actually help feed into cycles that result in social breakdown and transgression.

“The more we police and criminalize communities, the more we destabilize and erode them. The more you criminalize a community, the higher the divorce rates are, the lower the education rates are, the worse the health outcomes,” he said.

“The only way we can prevent transgression is by boosting community and social development.… But police work really hard to try to convince people of the opposite.”

Leuprecht said the issues seen in Winnipeg with skyrocketing police costs are nothing new. In 2014, he authored a paper entitled: “The Blue Line or the Bottom Line of Policing in Canada? Arresting Runaway Costs.”

Some of the questions he set out to answer were: do we need police doing all the things they currently do? Are there other services that could better handle some of these tasks? How effective is policing in Canada?

His conclusion was the funding model for policing was broken and unsustainable, that policing in Canada was deeply inefficient and operated without transparency, and that much of what police do these days could be better accomplished by lower-paid civilians.

In 2016, former police chief Clunis said that roughly 80 per cent of what Winnipeg police officers do falls outside the scope of “traditional police work.”

Leuprecht further claims that crime rates — something union leaders and civic officials have pointed to as justifying increases to police budgets — are a “terrible indicator” of serious social transgression and public safety.

“In policing, we take what is measurable and we make it matter, as opposed to thinking, ‘What actually matters? And how do we measure it?” he said.

There is also no indication the quality of the service Winnipeg taxpayers are receiving is improving with increased funding to the department.

The number of sworn police officers in Winnipeg decreased by 59 — or 4.2 per cent — from 2011 to 2020. The ratio of residents to police officers has increased from 489:1 in 2011 to 566:1 in 2020, which is greater than the rate of population growth.

Clearance rates for property crime remained low throughout the decade, sitting at 13 per cent in 2011 and rising to 18 per cent in 2020. Clearance rates for violent crimes stayed flat at 59 per cent — with annual fluctuations — during the same period.

“What should be driving the police budget is, ‘What do we want our police force to do?’ Not the police chief saying, ‘I need three per cent,’” Leuprecht said.

And despite the significant funding increases over the years and generous compensation packages, the status quo does not appear to be working for WPS members, either.

In June, the city released the results of a third-party report into WPS morale, which was commissioned at the behest of the WPA.

A majority of officers (63 per cent) and civilian employees (53 per cent) said they feel their work is having a significant impact on their mental health, with nearly a third of police meeting the diagnostic criteria for PTSD, anxiety or depression.

Four per cent of officers and five per cent of civilian employees said they had seriously considered suicide during the past 12 months. And earlier this year, a WPS officer took his own life.

“Anti-police public opinion, COVID, negative media and internal politics are identified issues that have led to toxic organizational culture,” co-authors Lisa Kitt and Nathalie Gagnon wrote in the report.

In response to the findings, Sabourin said one thing was clear: the WPS needed more resources.

● ● ●

Winnipeg Police Service Chief Danny Smyth cautions against an apples-to-apples comparison of the city’s police budget with other municipalities.

While it is true Winnipeg is one of the highest spenders on police services in the country, Smyth said differing funding models employed by municipalities must be taken into account.

For example, the WPS must pay the municipal government to rent the facilities it uses. And due to cost overruns on the controversial police headquarters construction project, it also has significant debt payments each year.

“It’s pretty difficult to compare different municipalities and their police services… because we don’t do our funding the same way,” he said.

While Smyth has said in the past that he’s open to the idea of a reduction in police funding should crime rates fall and demands for service drop, he argues there are currently no other agencies capable of responding when calls come in. Last year, for example, police conducted 18,991 well-being checks, a 12.4 per cent increase from 2019.

“There is no other service that’s positioned to be dispatched…. Alternative service delivery really doesn’t exist in any meaningful way — at least not in our community right now,” he said.

“Therein lies one of the biggest issues. After hours, there is no one else other than police, fire and paramedics to respond to those calls. If we can start working with other service providers, that certainly could have an impact.”

That’s similar to what current Winnipeg Police Board Chairman Coun. Markus Chambers, and former police board chairman Coun. Scott Gillingham, told the Free Press in separate interviews.

They both pointed to a study the city has signed on to — the Harvard Bloomberg Initiative — that looks to address this issue. But for the time being, they said, there’s no one else to fill the gap.

“Who are you going to call? On a Friday night, if someone is in distress, the call goes to 911 and it’s the Winnipeg Police Service who gets dispatched,” Chambers said.

Gillingham agrees that some funding for emergency services needs to be reallocated but said that can’t happen until “other agencies are in place” or the city has forged relationships with “other service providers.”

Critics such as Walby and Setlack counter that it’s no surprise other agencies aren’t able to fill the gap when they’ve been starved of funding for the past two decades.

Walby maintains that funding for the WPS is “absurdly high, whether it’s benchmarked against other police budgets, or it’s just looked at within the context of Winnipeg’s municipal spending.”

And even fiscal conservatives such as Kelcey and MacKay — both of whom stress they support the role of policing in society and want to see officers well-compensated — argue the status quo will result in serious problems down the line.

The collective agreement between the City of Winnipeg and the United Fire Fighters of Winnipeg expired Dec. 26, 2020.

Due to a missed deadline for filing contract proposals, it appears the city has squandered its opportunity to end a controversial practice that has seen taxpayers cover a significant portion of full-time union boss Alex Forrest’s salary for years.

By March 2021, the UFFW filed for binding arbitration. The union did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

For its part, the WFPS said in a written statement that it is unable to speak to “department-by-department funding allocations.”

“(The) WFPS relies on highly skilled firefighters, paramedics and 911 staff. Collective agreements typically provide for annual wage increases and health and wellness benefits, which are considered in line with other jurisdictions,” newly minted Chief Christian Schmidt said.

“The department is committed to doing (its) work as efficiently as possible while ensuring high levels of service to residents and ensuring WFPS members have the resources, training and support required to do their job safely.”

Meanwhile, the collective agreement between the Winnipeg Police Association and the City of Winnipeg is set to expire at the end of this year.

It remains to be seen if arbitration can be avoided, or if city negotiators can get the union to concede to a compensation agreement that could slow down rising salary costs.

Whatever happens, Setlack argues you don’t have to look very far to find other municipalities tackling these issues in creative, forward-thinking ways.

In Regina, for example, political leaders have been working to find ways to address social problems before emergency services get involved. Much like in Winnipeg, the workload for their emergency services agencies was unsustainable.

“They identified social risk factors, they started using evidence-based decision-making, and prioritized multi-agency collaboration. They’ve been able to be proactive and preventative and work towards solutions that aren’t just reactionary,” Setlack said.

The City of Regina invested $3 million in funding for cultural and recreational programming by eliminating scores of managerial positions at city hall. And they’ve earmarked 0.5 per cent of future mill-rate increases for similar initiatives.

Setlack is adamant that such solutions are not out of reach here.

“This isn’t some city in Europe that’s doing this new-age approach. This is five hours away from us,” she said.

“If they can do it, why can’t we?”

ryan.thorpe@freepress.mb.ca Twitter: @rk_thorpe

michael.pereira@freepress.mb.ca Twitter: __m_pereira

Ryan Thorpe likes the pace of daily news, the feeling of a broadsheet in his hands and the stress of never-ending deadlines hanging over his head.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.