Brave but too-badly broken Winnipeg teen’s life shattered by predator coach Graham James; after decades of silent shame-fuelled torment, he told his story to Free Press reporter, who became a trusted friend

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/04/2021 (1790 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

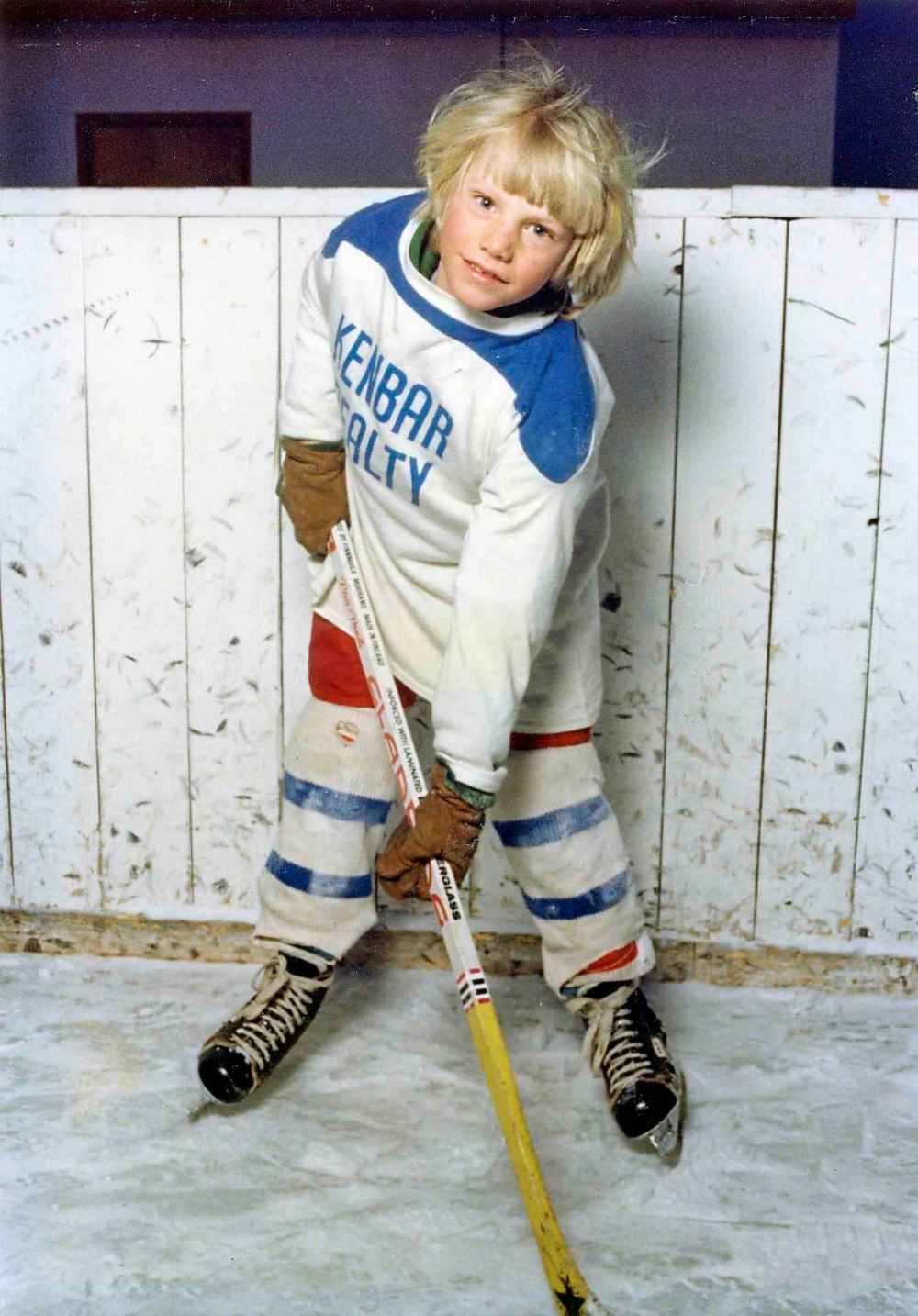

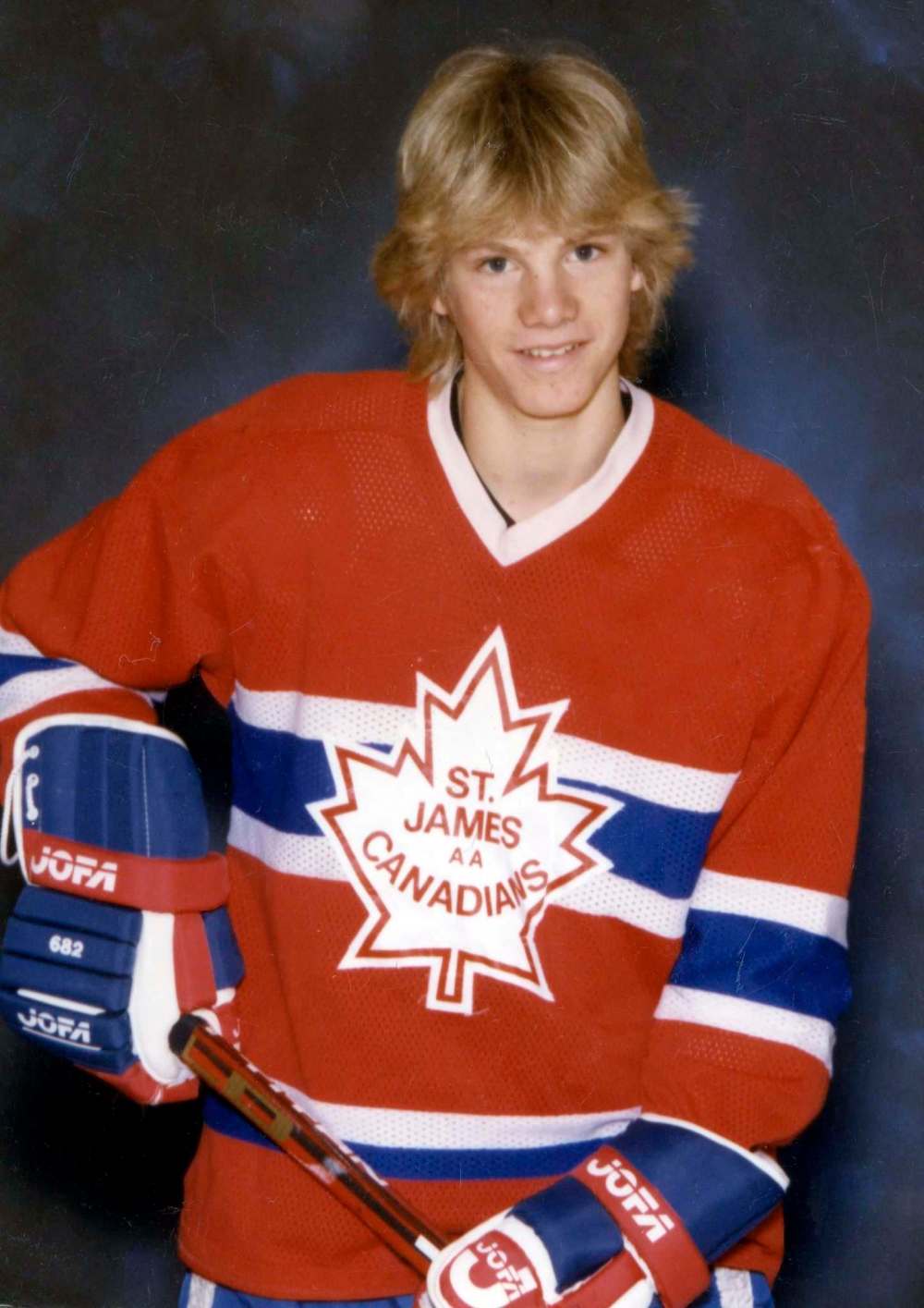

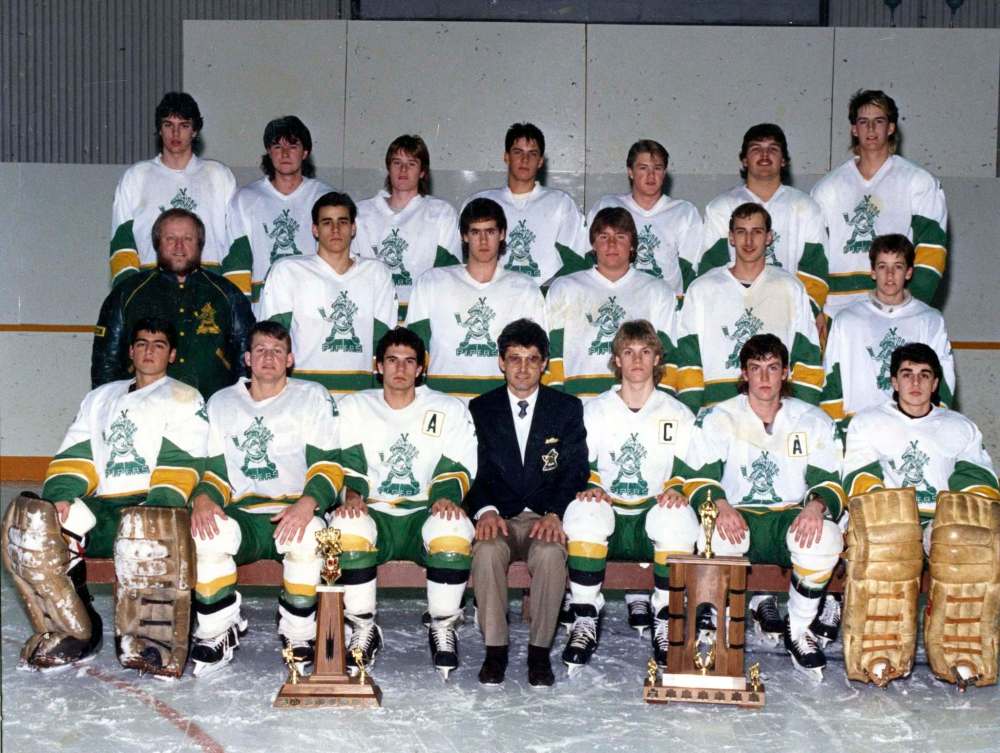

Free Press readers were first introduced to Jay Macaulay last December. Macaulay’s journey, from Winnipeg hockey star to sexual assault victim, was the centrepiece of sports writer Jeff Hamilton’s investigation into the legacy of sexual predator and disgraced hockey coach Graham James.

Macaulay revealed publicly for the first time, in unflinching details, the abuse he suffered as a member of the Swift Current Broncos team James coached in the late 1980s and how his life was irreparably damaged.

In the months that followed, his life was marked by hard-fought triumphs and, ultimately, tragedy. On Sunday, Macaulay died of an overdose at the age of 50.

●●●

Over the last several days, I’ve received dozens of emails and messages on social media from people, many of whom are strangers, wanting to inform me of the untimely death of Jay Macaulay. It’s important I start off by thanking those who reached out, for your genuine care and kind words. They’ve helped make a tough week feel more manageable.

Truth is, I never stopped talking to Jay. We spoke nearly every week over the past two years. And it was only last Thursday we were exchanging celebratory texts after Jay successfully graduated from the nearly four-month program at Fresh Start Recovery Centre in Calgary — one of the country’s top addiction-treatment and transition programs in Canada.

I met Jay in August of 2019, while working on an investigation into Graham James. The abuse he suffered as a teenager sent his life into a downward spiral, leading to decades of emotional pain and addiction, as well as long stretches in prison.

It was while out on probation, after working for years behind bars to get his life back on track, that I first met Jay at Winnipeg’s downtown train station.

I was early into my research on James and can recall experiencing a range of feelings — intrigue, some skepticism, anxiety — about meeting someone who had been hardened by a dependence on drugs and countless interactions with police.

A Stain on our Game: About the project

In this multi-story series, Free Press sports writer Jeff Hamilton investigates the past of disgraced junior hockey coach Graham James — from his formative years growing up to his time as a substitute teacher, and from his first foray into coaching minor hockey to his ultimate downfall.

Hamilton gives voice to James’ victims and talks to dozens of former players, childhood friends, colleagues and officials, asking questions of those who knew — or ought to have known — what was happening on their watch.

What began as a first meeting between interviewer and interviewee evolved into a cherished friendship. While Jay’s family, some of the best people I’ve ever met, have thanked me for my care in working with him, what I gained from our relationship is invaluable.

While Jay’s story shows a life haunted by the sexual abuse he endured, the consequences of drug and alcohol addiction and the hope of coming out the other side healthy and happy, there’s a different part of Jay’s journey that needs to be told now.

If I’ve learned anything, it’s that the effects of sexual violence and substance abuse rarely follow a tidy story arc, and the path is often filled with unwavering pain that ripples through other people’s lives.

There is no point in sugar-coating here. This is real life with real consequences, and providing a watered-down version of events only helps perpetuate the tendency to look past the ugly parts of sexual violence and addiction. Jay’s story is not unlike many who have faced similar circumstances.

There aren’t many families that haven’t been affected in one way or another by childhood trauma, sexual abuse and addiction. Despite the efforts of many working to normalize that fact, there’s still plenty of work required to break the stigma.

After our initial meeting, Jay and I met in person every couple of weeks, exchanging texts in between. While it would take a couple of these sessions to discuss the painstaking details of James’ abuse, the talks eventually shifted to other, less-troubling topics.

Soon we were just talking. We talked about how much he loved his young daughter and how it was important he focus on improving himself first before re-entering her life. We talked about the relationships he had damaged over the years, and what might be the best way to repair some of them.

More often, though, it was like talking to a buddy. We discussed the Jets, a team Jay supported through and through. We talked about plans for the future. Most calls would end with the same vision: that one day, years down the road, we would be sitting on a patio drinking diet colas, looking back on everything Jay had accomplished. That always ended with an important caveat: that we focus on today first.

Jay’s recovery journey was far from perfect. While out on probation he felt overwhelmed and missed a meeting with his probation officer, sending him back to prison. That only seemed to increase our contact, with Jay calling me from Stony Mountain Institution multiple times a week.

From there, our conversations shifted to be more proactive in his recovery. I made a pledge with him that if he was going to start investing in his mental health then I would, too. We shared best practices for managing stress and anxiety, including meditation. We stressed that feeling sorry for ourselves was a waste of time and energy, and that if we wanted something bad enough we could achieve it. Jay always noted how much better he felt with a clear mind.

But what became cruelly obvious was that the structure and routine that was offered in prison, even if it’s an overall horrible experience, was no longer there for him on the outside. It didn’t help that COVID-19 prevented Jay from visiting a gym. Before going home, Jay’s daily routine included three separate trips to the gym, where he spent hours working out.

Upon his official release, it wasn’t long before he went back to drugs. With Jay’s blessing, as well as from his family, we pressed on with the story.

Within days of publishing, I received well more than 100 messages about Jay. Letters came from old friends and former classmates and teachers, all saying how much they appreciated him, how kind he was as a teen — even for a tough hockey player — and that he had this gift where people just gravitated to him.

Medical professionals offering free counselling contacted me. Other people told me that Jay’s strength helped them disclose their own abuse or encouraged others they know to do the same. Many described their own struggles with sexual assault and/or addictions and wanted to share how proud of Jay they were for taking his story public, how powerful that was for survivors to read.

Many also passed on messages for Jay. I read him every single one, often with tears streaming down our faces. There were so many beautiful words.

Given Jay had relapsed so quickly, I knew he wasn’t going to succeed on his own. With the help of Sheldon Kennedy, someone I respect as much as anyone in this world and who was the first to come forward against James more than two decades ago, Jay got the opportunity to enter Fresh Start.

But before he would do that, Jay first visited Winnipeg’s police headquarters to file an official complaint against James. I remember sitting in my car, as he sat slumped in the passenger seat of the vehicle parked next to mine. He looked pale, his skin almost translucent, and his speech was dragging. He looked so ashamed; as I’ve always told Jay, there will never be judgment from me. It was one of the many times I told him how proud I was.

When Jay entered the treatment centre, it was the first time that we stopped talking for a stretch of weeks, to give him less responsibility as he integrated into his new program. When we finally caught up, he told me he had to literally crawl into the facility; that’s how weak the drugs had made his body.

But after ridding himself of the poison inside, Jay seemed to thrive. He was meeting new people who faced similar struggles and was gaining confidence through various workshops and work placements set up by the program. Most noticeably, he sounded like the old Jay, with energy back in his voice and an eagerness to move on from the past.

He texted me last Thursday with two pictures from his graduation, and a message that read, “Made it.” I told him he should be proud, that I was so proud of him. I said this stretch hasn’t been easy and it won’t be moving forward, but with an army of support behind him and a number of new tools to help resist temptation, it could be the start of better days.

The last time I spoke to Jay was two days prior. He told me that for the first time in a long time he felt loved. He said he was nervous but prepared for the future and wanted to make sure once again that I was OK to have my name added to his list of supporters.

He then told me about a wall they have at Fresh Start, covered with pictures of men that graduated from the program only to die afterwards, losing their battle with addiction. He didn’t want to be on that wall.

Jay returned home Saturday and by Sunday night he was gone. He made it 24 hours.

There are questions that we will never get answers to; perhaps that is the worst part behind losing a friend, brother, uncle and father.

People have asked me why I chose to stay connected with him. Maybe it was the fact that Jay’s life wasn’t ever easy, even before he encountered James, or that he was painfully open about his own misgivings.

Never once did he paint himself as a victim, though he certainly was, but he did understand the need to share his story as part of his healing journey. He was coming to grips with what happened in Swift Current and how it shaped his future, and knew that despite a horrific experience he was responsible for his own decisions later in life.

Or maybe it was that I saw myself in Jay, as another St. James kid that walked the same school hallways and played in the same hockey system and faced some of the same challenges growing up. Someone who was a bit of bad luck away from suffering a similar fate.

Knowing Jay made me a better person — more empathetic, caring.

Knowing Jay taught me important life lessons and opened my eyes to the carnage left in the wake of sexual abuse and the lasting effects that can have on someone.

Knowing Jay introduced me to a network of supporters that helped me share his story, people who cared about a former friend enough to make his recovery part of their lives.

I’m sad and I’m angry. I’m angry at our court system that allows serial sexual predators like James to walk free while victims are forced to try to pick up the pieces left behind. I’m angry that there are hockey men out there, including here in Winnipeg, who still credit James for his work in the game and downplay the misery experienced by the many kids he manipulated, assaulted and raped, leaving an indelible stain on the game we all grew up loving. I’m angry that Jay’s death will likely mean James will escape justice once more.

More importantly, though, I’m motivated more than ever to dig deeper and expose these injustices. This week has only strengthened my resolve to provide a voice for the voiceless.

It’s the only way I know how to truly thank Jay.

jeff.hamilton@freepress.mb.ca

Jeff Hamilton

Multimedia producer

Jeff Hamilton is a sports and investigative reporter. Jeff joined the Free Press newsroom in April 2015, and has been covering the local sports scene since graduating from Carleton University’s journalism program in 2012. Read more about Jeff.

Every piece of reporting Jeff produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.