Big dreams, shattered life Jay Macaulay was trying to crack the WHL Broncos’ lineup in the fall of 1988; instead he became one more of Graham James' victims

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/12/2020 (1916 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It’s a warm late-August afternoon and Jay Macaulay is sitting in the empty lobby of Winnipeg’s train station fidgeting with a pen.

He just finished putting a check mark in his day planner, indicating another successfully finished workshop he’s required to attend each week as part of his parole conditions.

He says he feels good after the workshop meeting and is in a much better mood than he was earlier in the day; he had an argument with his ex-girlfriend over something he can’t even remember now.

About this series

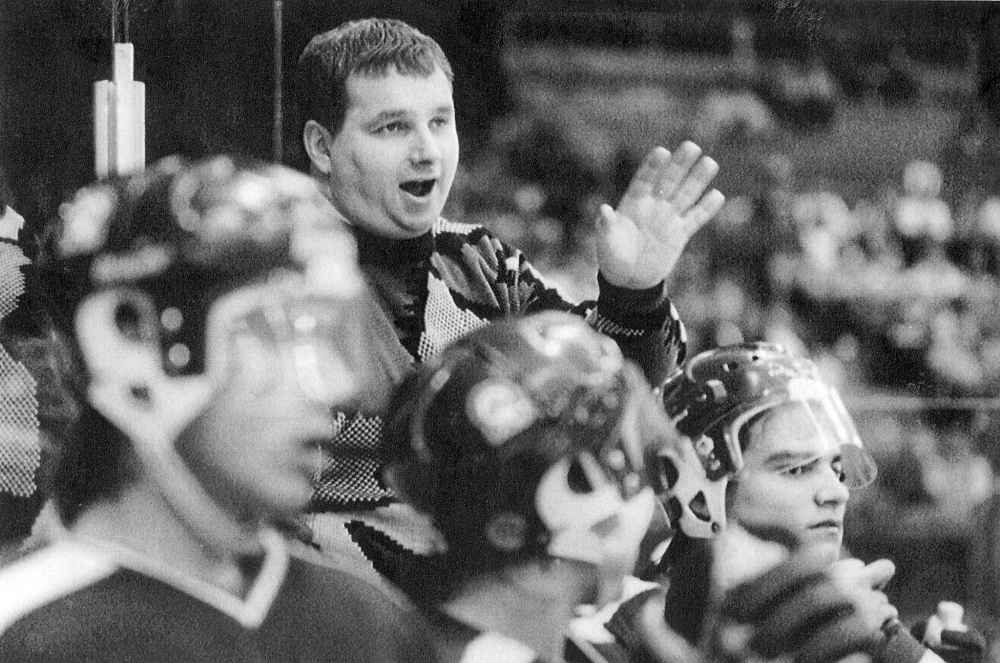

Graham James was last seen in a courtroom in the summer of 2015.

Appearing via video link from a Quebec prison, the disgraced junior hockey coach pleaded guilty in a Swift Current courtroom to sexual assault on one of his players during the early 1990s, and was sentenced to two additional years behind bars.

But that was not the end of the serial sex abuser’s saga; it was just one more chapter in his sordid life story.

Graham James was last seen in a courtroom in the summer of 2015.

Appearing via video link from a Quebec prison, the disgraced junior hockey coach pleaded guilty in a Swift Current courtroom to sexual assault on one of his players during the early 1990s, and was sentenced to two additional years behind bars.

But that was not the end of the serial sex abuser’s saga; it was just one more chapter in his sordid life story.

While a significant number of the assaults occurred in Saskatchewan, where he coached both the Western Hockey League’s Moose Jaw Warriors and Swift Current Broncos, the James scandal has always been a Winnipeg story.

James worked his way up through the ranks here — in Winnipeg minor hockey, the Manitoba Junior Hockey League and the WHL’s Winnipeg Warriors.

It was with this backdrop that Free Press sports writer Jeff Hamilton began investigating James’ past, from his formative years growing up as an Air Force brat in St. James to his time as a substitute teacher in the St. James-Assiniboia School Division, and from his first foray into coaching minor hockey to his ultimate downfall.

Hamilton interviewed dozens of former players, childhood friends, educators and hockey colleagues and officials.

His investigation reveals an awkward teen who found confidence both in the classroom and at the rink, one that enabled him to embark on his trail of destructive criminal behaviour.

The investigation also paints a picture of complicity or, at the very least, wilful ignorance through all levels of the sport, which allowed James to abuse young players for years.

In total, James has been convicted of sexually assaulting five former players: Sheldon Kennedy, Theoren Fleury and Todd Holt have all publicly shared their ordeals; the identities of two others have been protected by publication bans.

However, police estimate the true number of victims is between 25 and 100.

While powerful institutions, such as the Catholic Church, and prominent individuals, including Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein, have all had their moments of reckoning, there has been no equivalent to the #MeToo movement in hockey. This Free Press investigation attempts to change that narrative by giving voice to victims and asking questions of those who knew or ought to have known what was happening on their watch.

The latest victim to come forward is a former Winnipeg high school hockey star who crossed paths with James when he was trying to crack the WHL’s Broncos’ lineup in the late 1980s.

His story, from being sexually assaulted to his descent into drug abuse, crime and, ultimately, prison time, is the subject of Part 1 of a six-part series titled A Stain on Our Game.

Like him, she battles daily with drug addiction and though he’s been clean for two years, she still has an emotional hold over his life. She knows his triggers, Macaulay says, and when she’s high she can be especially difficult to deal with.

“Now that I’m sober, I can see all these people that used to be in my life struggling with the same problems I had,” says Macaulay, his 6-3 frame filling up his side of a small table. “What they’re dealing with is a death sentence.”

Weekly visits with a psychologist for sexual abuse trauma have opened Macaulay’s eyes to the destructive path his life has taken. And now, after sharing his secret behind closed doors for the last two years, he’s ready to open up.

Macaulay draws in a long, deep breath. Then he quickly gets into it, providing detail after excruciating detail of how, over parts of two years in the late 1980s, he was sexually abused by his junior hockey coach, Graham James.

Macaulay says that during stints with the Western Hockey League’s Swift Current Broncos between 1988 and 1990, he was subjected to abusive behaviour by James, including inappropriate touching, oral sex and, on one occasion, anal rape.

It’s been a long journey from then to now, with unimaginable stops along the way. Macaulay isn’t looking for sympathy — God knows he’s had his share of second chances — but he hopes by sharing his story he can continue to heal. And in doing so, get a better understanding of how a once-promising opportunity would upend his life, sending him on a roller-coaster of destruction that still haunts him.

“It’s only now, through the help of talking to professionals, that I’m starting to realize the role it’s played in ruining my life,” says the 49-year-old Macaulay.

“It’s only now, through the help of talking to professionals, that I’m starting to realize the role it’s played in ruining my life.”

Macaulay’s revelation is the first to emerge since 2015, when the now-disgraced coach pleaded guilty in a Swift Current courtroom and received a two-year sentence for abusing another, unnamed Broncos player months after Macaulay escaped the team for good.

Macaulay’s struggles are just a tip of an iceberg; police still believe there is a much deeper depth of despair, involving many more victims, left in James’ wake.

James has been convicted of sexually abusing five former players — though police suspect the number of victims is significantly higher — including hundreds of incidents against former Manitoba NHLers Sheldon Kennedy and Theoren Fleury.

James was sentenced to a combined 10 1/2 years on three separate plea deals. He was also handed an additional six-month concurrent sentence, also a result of a plea deal, stemming from an indecent assault charge on a 14-year-old boy in 1971 when James was 19. Because he was repeatedly granted parole, he shaved years off his time behind bars.

Although most of the assaults occurred in Swift Current during the eight years James was coach and general manager of that city’s Western Hockey League club, the Graham James saga has always been a Winnipeg story.

His formative teen years were spent in St. James. He began coaching minor hockey in St. James, where he was also a substitute teacher, before moving to the Manitoba Junior Hockey League. With that as a backdrop, the Free Press undertook an investigation to explore the life and destructive legacy of Graham James. This is the first instalment in a six-part series.

Macaulay contemplated going to the police with his story, but says he has had some concerns; while he received a fair amount of support from other inmates during his time in prison, he says it can be a dangerous game to be seen speaking to police while incarcerated.

Now that he’s out, his primary focus has been on getting healthy. Macaulay hasn’t ruled out pursuing legal action, but the thought of re-engaging with the justice system immediately after leaving it is too overwhelming right now.

●●●

Over a period of months in 2019 and throughout 2020, Macaulay sat down with the Free Press every two weeks. The chats often continued for hours.

He spoke about his childhood growing up in St. James and the events that led to an invitation to the Broncos training camp. He spoke about making the team, as surprising as it was for a high school player at the time to make such a jump to major-junior hockey, and then the escalating abuse that followed during three separate stints over two seasons with the club.

And he spoke about his current troubles, his criminal past, and how, despite taking major steps to improve his life, demons are always lurking nearby.

“If it weren’t for jail, I would have never got off drugs. I probably would have ended up dead or something,” Macaulay says. “But by sharing my past, it’s at least getting me better now.”

Rotting away in a Stony Mountain Institution prison cell wasn’t enough inspiration to turn his life around, nor was being surrounded by some of the country’s most hardened criminals. It wasn’t until a guest speaker visited the prison in January 2018 and a few inmates convinced Macaulay to attend, that he finally took what turned out to be his first step toward recovery.

Macaulay is not superstitious, but he doesn’t dismiss fate working in mysterious ways. How else, he asks, can Theoren Fleury’s visit to speak at the prison at the same time he was imprisoned be explained?

James abused Fleury for years, beginning when the diminutive hockey phenom from Russell was a teenager. It was only after James was demoted as head coach and then quit the Moose Jaw Warriors following the 1984-85 WHL season that Fleury was able to escape the assaults.

“He’s on stage doing a speech and, I swear, he’s looking right at me,” Macaulay says. “At that moment I knew I had to do something. Tell somebody. Anybody.”

His first thought was to write Fleury a letter. But he didn’t want to bother the former NHL star, whose career included winning the Stanley Cup and Olympic gold, but who also struggled with addictions as a result of the abuse James put him through. It also didn’t seem immediate enough, and Macaulay didn’t want to lose his sudden momentum.

“He said that if you don’t get help, you’re not going to get better,” Macaulay says. “A day later I went to see a psychologist. It was finally time to open up.”

●●●

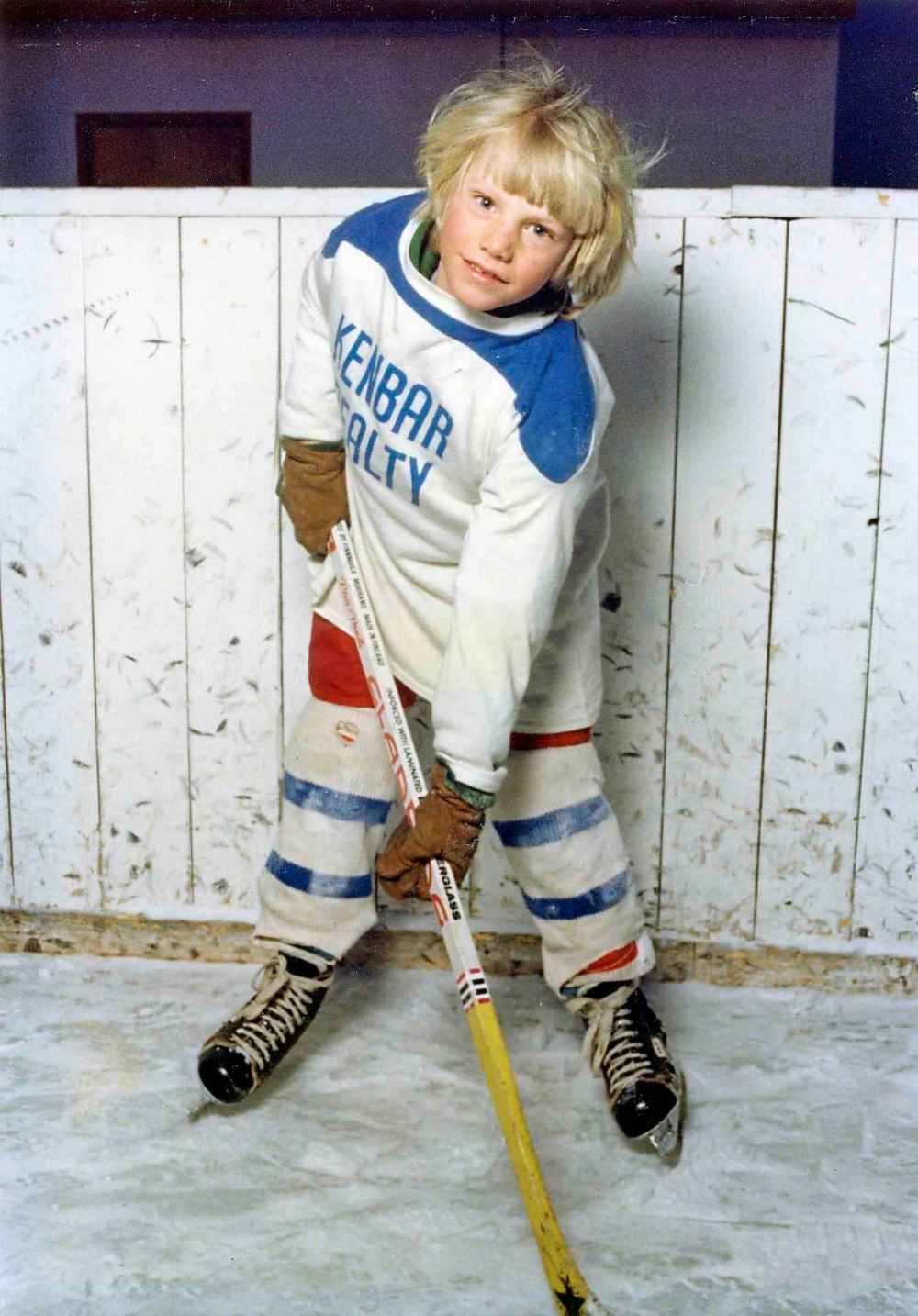

Born John Jay Macaulay to parents John and Lynne, he was the youngest of three kids. He lived in a middle-class home in the Crestview area of St. James.

Macaulay has few childhood memories. He credits his drug abuse for that but then adds his psychologist believes he’s also suppressed some, in part, because of his upbringing.

He loved his father but admits he was rough with him often; he battled with his older brother, too, even if they had a better relationship. It was in this environment he first learned how to defend himself.

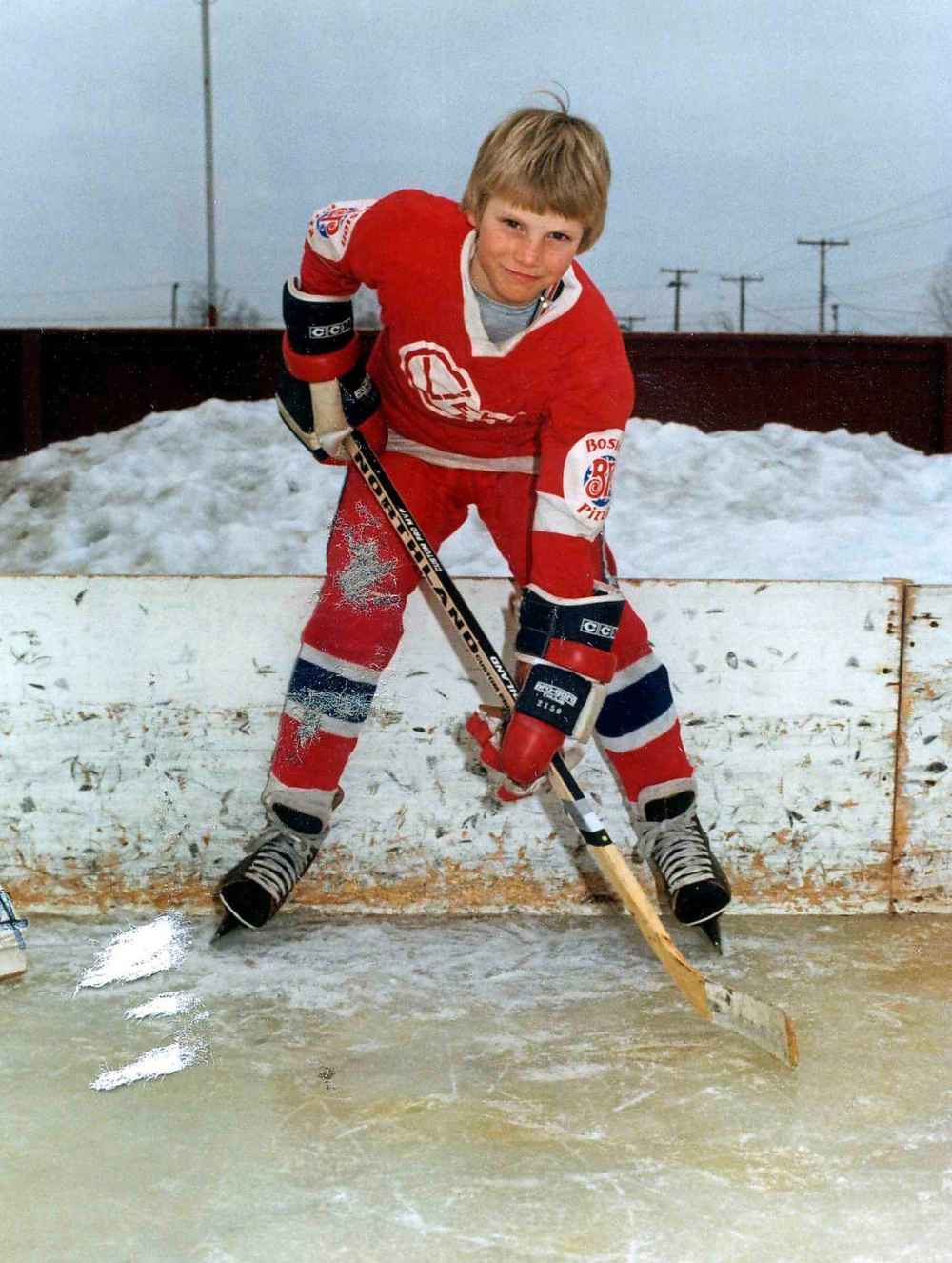

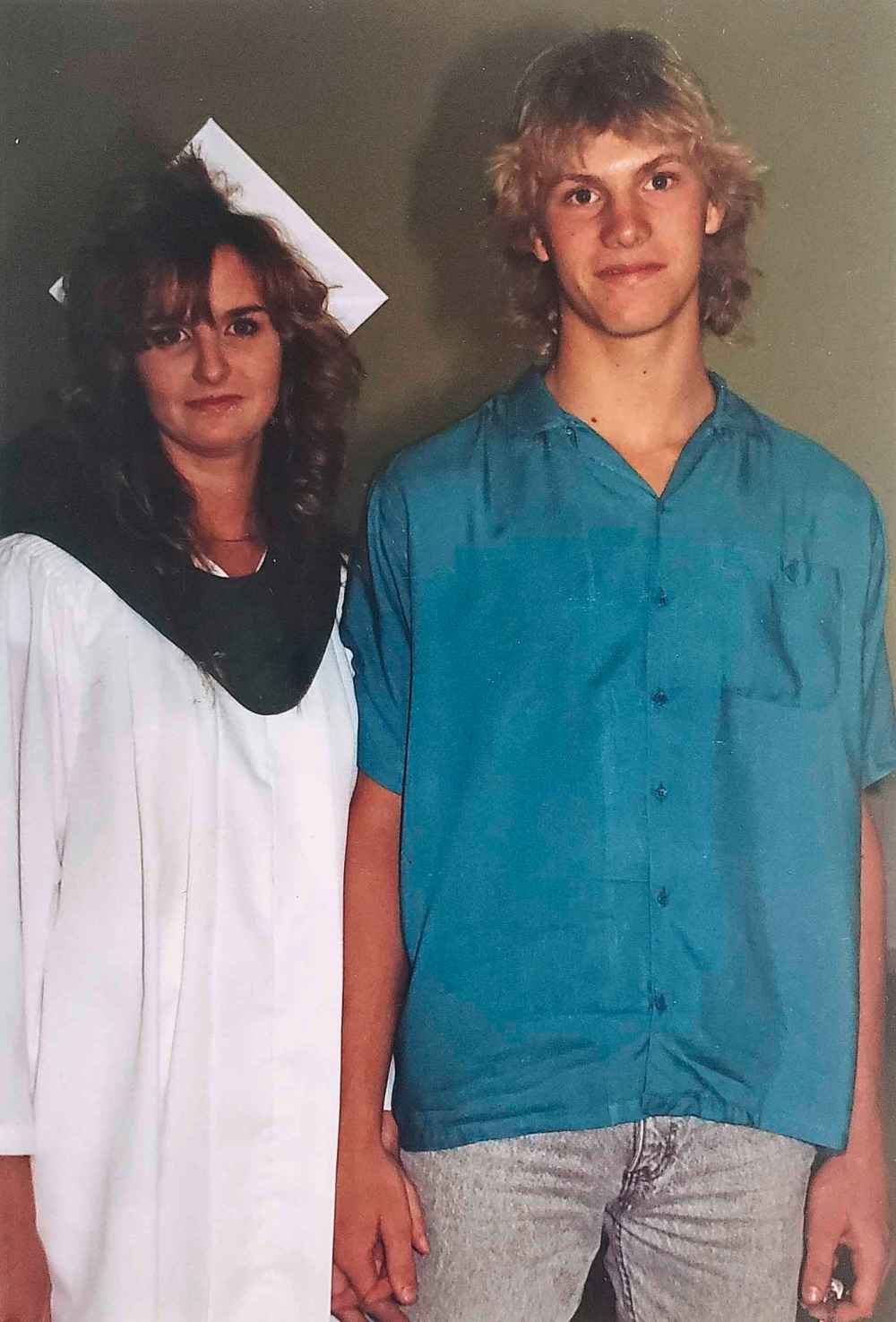

By the time he reached high school, puberty had blessed Macaulay with a tall and fit frame, as well as the kind of long blond locks that screamed Hollywood movie prom king. He was quiet, yet confident, and was active in sports and enjoyed hunting — a hobby he picked up from his father.

Peter Anadranistakis was a friend and a former teammate of Macaulay’s on the John Taylor Collegiate Pipers hockey team. He described Macaulay as “tall and lanky and tough as nails.”

“He would never go asking to fight, whether on or off the ice, but I guess because he was kind of tall and skinny he attracted a lot of attention,” says Anadranistakis, an entrepreneur who now splits his time between Winnipeg and Phoenix. “Let’s just say I never saw him lose, not even once.”

It was Anadranistakis who encouraged Macaulay to speak to the Free Press after reconnecting with him over Facebook. Having lost contact with Macaulay for decades, and unaware of his downward spiral, he was saddened to see a once-promising teammate now look almost unrecognizable. He wanted to help out, and part of that was encouraging him to speak publicly about his story.

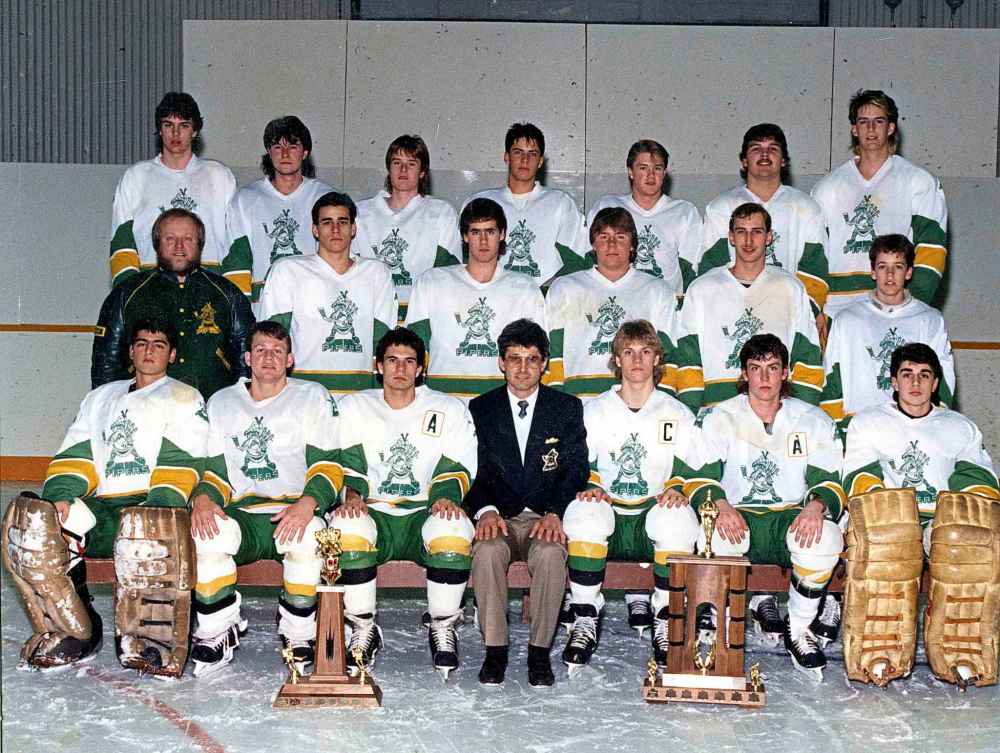

Though Macaulay earned a name for himself due to his toughness, he wasn’t just a pair of fists. In fact, he had the respect of all his teammates and coaches, so much so that when they looked to name a captain for the 1987-88 season, he became the obvious choice despite being in Grade 11.

The Pipers went on to win the Winnipeg high school hockey league title that year. When it came time to take the year-end photo, there is Macaulay, seated in the front row with the “C” near his heart and the championship trophy in front of him.

“I was really pumped up with my high school team,” he says. “It’s a reminder that I was once a leader in my life.”

Though not the fastest nor most skilled, Macaulay was the team’s most well-rounded player. It helped that he had size — he clocked in near 6-3, 190 pounds as a teen — and was willing to use it wherever and whenever necessary.

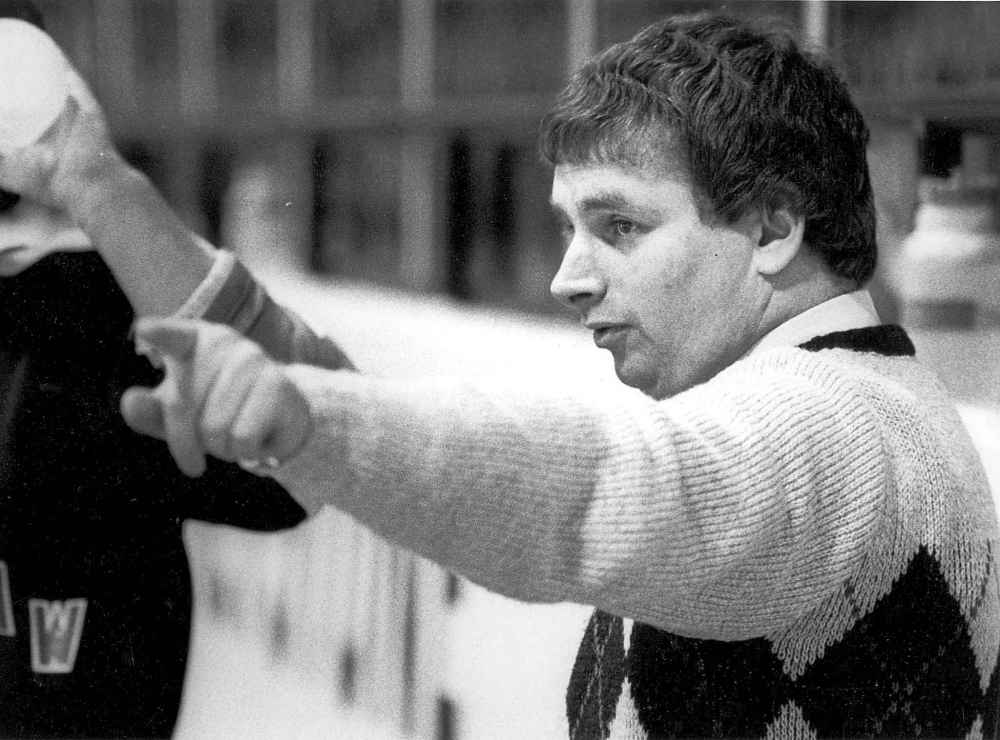

“He had hands on him like a gorilla,” recalls Tom Trosky, who coached Macaulay for two seasons with the Pipers. “He was a spark plug, so much so that when he was in Grade 10 all the Grade 12s would listen to him because he was a tough mother. But he was a gentle giant, too. Let’s put it this way: if you wanted to fight, well, he’d fight you.”

Trosky, a longtime teacher at John Taylor before retiring in the late 1990s, admits he always had a soft spot for Macaulay. So did his wife, Sharon, who couldn’t help but wonder why the young man was dealt such a tough hand in life.

Macaulay’s situation at home was well-documented at the school, and the guidance counsellors, eager for an update, would often approach him in the hallways. Trosky remembers that for a brief time Macaulay was sleeping in his father’s car after the two got in a heated argument.

“From what I knew, his home life was more than just a little bit tough,” Trosky says. “And he was such a shy guy, I mean, my wife fell in love with him because he was just drop-dead gorgeous — tall, blond-haired guy — and she felt sorry for him.”

Trosky recalls running into Macaulay on the street years later, his wife by his side. They exchanged pleasantries but something didn’t seem right. Macaulay turned red in the face. He looked ashamed.

“He seemed like he might have been going through some tough times again,” Trosky says.

●●●

Macaulay remembers a few WHL teams were scouting him at the time, including the Seattle Thunderbirds.

He doesn’t remember who he talked to from Seattle, but he’ll never forget what they told him when he called to say he had chosen Swift Current. It was one of a few warning signs that went over his head.

“I think it was one of the coaches and he tells me that I’ll do well there, that Swift Current likes the pretty boys,” Macaulay says. “They said it would be better for me in Seattle but I didn’t listen to them.”

Then there was the conversation he had with Cam Caldwell, a longtime Winnipeg ref who also was a local scout for Swift Current. Caldwell rode shotgun as Macaulay drove the eight-hour trip to Swift Current for training camp in the fall of 1988.

They spent much of the drive listening to music. Macaulay says Caldwell made him feel appreciated, saying that if he worked his butt off there was a good chance he’d make the team. At some point, though, the conversation turned.

“He says to me, ‘Jay, I want to tell you that you got to be careful with Graham. He likes young boys,’” Macaulay says.

Much like his conversation with Seattle, Macaulay thought it was weird but he didn’t give it much thought. His primary focus was on playing in the WHL.

“He’s trying to tell me that Graham likes little boys and that the whole town knows about it, but that it’s just accepted there,” Macaulay says. “I don’t remember a lot of things but I remember things like that. Like, how can I not remember that?”

Caldwell, the Manitoba scout for Swift Current from 1986 to 1991, says he not only remembers Macaulay, but that he was responsible for getting him a shot with the Broncos. He first noticed Macaulay in minor hockey and by the time he was a teenager he saw great potential in him to move on to the next level.

“I thought he was a decent player — tall, lanky, pretty good skater, decent puckhandler — who had a lot of skill to his game. On top of that, he was also quite tough,” Caldwell says. “I know that Graham James, his idea for recruiting Jay was more to be a tough guy and fight but Jay had more skill than that.”

”There’s not a chance in hell I would have sent a player out there knowing he was a predator.”

To get Macaulay to commit to the Broncos, Caldwell says he first had to convince his family. He said he met with Macaulay’s father and older brother and “was able to persuade the family to put their trust in me and the Broncos.”

However, he disputes Macaulay’s recollection of their drive to Swift Current. Caldwell says he had no idea — nor had he heard any stories by that point — that James was gay or was sexually active with young men. It wasn’t until years later, after he was finished scouting, that he had even heard a rumour.

“When it comes to Jay, truthfully I don’t recall making any sort of comment like that to Jay and I never, ever, would have put any young man — still a teenager — in any jeopardizing position whereby some predator could have done something,” he says.

“I thought I knew Graham pretty well… but there’s not a chance in hell I would have sent a player out there knowing he was a predator.”

●●●

Macaulay had been a dominant presence in Winnipeg’s high school circuit when he hit the ice for his first tryout with the Broncos, but his hockey resumé paled in comparison to the skaters around him.

Of the 29 players who suited up for the 1988-89 Broncos, 20 went on to play professional hockey, with five making it to the NHL. Sheldon Kennedy would become the most successful from that year, logging 310 NHL games over eight seasons with the Detroit Red Wings, Calgary Flames and Boston Bruins.

Still, Macaulay says he was unfazed by the talent around him and, unlike those who were drafted into the Broncos organization, he was motivated by the fact few knew his name.

Oddly, he knew little about his coach, too. At the time, many considered James one of junior hockey’s top bench bosses and, later that season, he was named Hockey News Man of the Year after guiding the Broncos to their first Memorial Cup championship.

Macaulay had no idea James had coached a number of teams within the St. James Canadians system, the same minor-hockey organization he grew up playing in. He was also unaware James was a substitute teacher in the same school division and had taught at John Taylor Collegiate.

Living in his own world most of the time, he was more focused on his own game and the opportunity to play at the highest level. If he could make the Broncos, he’d be one step away from fulfilling a lifetime dream of playing in the NHL.

Looking back, he fears the only reason he made the team was because of his looks. And given his rocky situation at home, he was the ideal problem child James became known to prey on.

“I wonder, did he know about me? My home life?” Macaulay asks.

“I wonder, did he know about me? My home life?”

It wasn’t long after making the Broncos that he was asked to meet with James. Up to that point he had little interaction with the coach and had never been alone with him, he says.

Like many of his recollections, the details are blurry. Macaulay doesn’t remember why he was asked to join James in his office but he recalls wearing dress clothes because the team had just finished a formal inter-club scrimmage between Team White and Team Blue — an event many junior teams use to show off new faces and create hype for the season.

Macaulay says he was sitting across from James when he was asked if he felt comfortable. He said he did. James then stood up and slowly moved to the other side of the desk.

“He was concentrating on my tie, getting close to me,” Macaulay says. “Like, I could literally smell his breath and he was making me feel uncomfortable. That’s what I’ll always remember, his smell.”

”That’s what I’ll always remember, his smell.”

James, now standing over top of him, reached down and placed his hand on Macaulay’s crotch, grabbing at him over his pants.

The incident lasted just minutes, but it felt like an eternity to Macaulay.

“I look back now and he was obviously doing that to me to test the waters,” Macaulay says, his voice softening. “I didn’t like him after that. You know what I mean? I didn’t like him after that.”

The incident shocked and confused Macaulay. He attempted to push his feelings deep inside, even going as far as convincing himself it didn’t happen, or at least not the way his mind kept telling him it had.

It would be impossible to escape, no matter how hard he tried. He was barely 17 at the time and he would soon become overwhelmed with shame and embarrassment, wondering how he could let something like that happen.

Then he started to hear the rumours. Among them, players joked about how James and Kennedy were having a sexual relationship. To hear him explain it, it was as if everyone in town was in on the deep, dark secret.

“I knew they were living together, or at least spending a lot of time together, and it was just hard for me to believe,” Macaulay says. “Where I grew up, people looked down at being gay. And I was a rookie, I couldn’t really… I thought if I was to speak up at all I’d be told to shut up or get punched out.”

Finally, Macaulay decided enough was enough. He wasn’t getting into games and he wanted to go home. He can’t remember if he asked for his release or if he just left.

He had been a Bronco for just three weeks.

●●●

By the time Macaulay was ready to return for training camp the next fall, his life had already begun to unravel.

He no longer trusted authority figures and had been kicked out of high school for smoking marijuana — a habit he says he first picked up in Swift Current.

Once a gentle giant, he now started to pick fights on the ice, embracing the role of enforcer with the Manitoba Junior Hockey League’s St. James Canadians. Macaulay was considered among the toughest players in the league, a designation that he says inevitably led to “everybody wanting a piece of him.”

Unable to control his emotions and feeling like he was always at odds with his coach, Macaulay quit the Canadians just as they started their playoff run in the spring of 1989.

“I was rebelling, fighting lots, getting in trouble,” he says. “A lot of that year is a blur to me.”

Though there were other uncomfortable moments with James during Macaulay’s initial short stint in Swift Current, the incident in the coach’s office was the only time he was touched sexually. That made things easier to forget, easier to suppress. So when the Broncos asked him to return the following season, Macaulay agreed, convinced the worst was behind him.

But he had a hard time making friends on the team; during one road trip, he broke his hand in a fight with a teammate.

Some players even went out of their way to intentionally mess up a drill so he’d get punished — a tactic James would often use to alienate a player. Macaulay would then be forced to stay late after practice, where he would either put in extra work on the ice or do chores off it, such as cleaning the locker room.

Staying late created the perfect environment for James to isolate his victim. Over time, James became more aggressive each time they were alone.

At first, James would watch him as he showered. Eventually, James joined Macaulay in the shower, their naked bodies in close proximity. Macaulay says it was extremely uncomfortable sharing the shower with his coach, but he did his best to ignore James.

Macaulay’s silence seemed to enable James. He started to request Macaulay give him massages. It would begin with James spreading out on the trainer’s table, with Macaulay rubbing his back and shoulders. Sometimes, when James wasn’t in the mood to be touched, he would get Macaulay to model equipment, watching intensely as he pulled pieces of hockey gear on and off.

As if to offer tangible proof of these incidents after all these years, Macaulay lists off another lasting image of James: how he always used to wear a white T-shirt, his large belly hanging out the bottom, and a pair of tight Puma sweatpants.

It was while dressed in that outfit following a massage, that James convinced Macaulay to give him oral sex for the first time.

“I’ve always asked myself why did I allow this to happen? But I was being groomed,” Macaulay says, echoing what he’s learned from trauma experts. “Nobody knew how messed up I was. It was a bad atmosphere.”

“Nobody knew how messed up I was. It was a bad atmosphere.”

At that point, Macaulay felt he was in too deep, that there was no longer an easy escape. It was one thing to give massages and walk around naked; it was another to be part of a sexual act. He blamed himself and wrestled with the notion that maybe he was gay. He knew he was interested in girls and had never been sexually attracted to men, but how else could he explain what had happened?

He didn’t feel he could tell his teammates, many of whom still hadn’t warmed up to him. He was considered an outsider for how little fanfare was attached to his name — just a high school player who had somehow managed to crack a lineup of budding stars.

Some teammates went as far as to tease him for what they assumed he had to do for James, which included jokes about massaging the coach, Macaulay says.

He also didn’t think anyone would believe him. And if they did, he feared he’d be blamed for it or, worse, be grouped in with James in hockey purgatory forever.

“It got to a point where I was scared to do a drill because I knew I would have to stay late and he’d be like a monster waiting for me,” Macaulay says. “It didn’t feel real to me.”

“It got to a point where I was scared to do a drill because I knew I would have to stay late and he’d be like a monster waiting for me.”

Complicating matters was Macaulay was now getting the chance to compete in games, earning real ice time. If he could crack the regular lineup, he figured, he wouldn’t have to stay after practice. Instead, James’ interest in spending time with him only seemed to increase.

In addition to his love of hunting, Macaulay also took a liking to nature, with a particular interest in birds.

James became aware of this and would use it as an excuse to spend time with Macaulay away from the rink. They’d go on long drives to some of James’ favourite spots to hunt geese.

On one ride, James asked Macaulay if he wanted to go for dinner at his place afterwards. Macaulay vaguely remembers James telling him he had a gun collection and that he should come over and see it.

After dinner, Macaulay says James motioned they should go to the couch, where he asked to be massaged. Soon after, James raped Macaulay, leaving him to walk home.

“This was supposed to be a dream come true. It didn’t just destroy my love for hockey, it destroyed my mental state.”

“I couldn’t tell you what I did that day, or what I ate for dinner. But I’ll never forget the blood,” Macaulay says. “This was supposed to be a dream come true. It didn’t just destroy my love for hockey, it destroyed my mental state. It crippled me.”

He would play just two regular-season games for the Broncos, recording one assist and nine penalty minutes.

●●●

Few people understand the toll Swift Current took on Macaulay better than Cindy.

Cindy, who works at a law firm in Winnipeg, first met Macaulay in grade school and the two were later high-school sweethearts, dating on and off for nine years. She describes their relationship as “that high school couple” — she was student council vice-president, he was captain of the hockey team.

They were together when Macaulay left to chase his dream of cracking the lineup of a WHL club. She was also there when he returned, and watched as he spiralled out of control.

Cindy, who doesn’t want her last name used, had recently reconnected with Macaulay after years without contact. She sent him a couple of Facebook messages, including one over Christmas in 2019, but was unaware he was in prison.

When he got out on parole in July of this year, Macaulay messaged her back on the advice of his therapist, who was encouraging him to reconnect with the positive people he’s had in his life. He told Cindy how miserable prison made him and the efforts he was making to better himself. He shared how drugs had harmed his mind and that he was slowly getting a handle on his mental health.

They had been texting for three weeks when Macaulay found the courage to talk about his time with the Broncos: “Do you remember when I went to Swift Current?” he texted.

“I knew where he was going, and I literally just bawled my eyes out as soon as he told me,” Cindy says during a lengthy phone interview. “I was shaking. I was angry because I knew something had happened out there.”

”Jay was, like, textbook to what happens when a teenage boy has some man mentally overpower him.”

That conversation lit a fire. Cindy spent the next two weeks researching childhood sexual abuse and watching documentaries about James’ time in Swift Current. She also looked through items she had kept from that era for any clues she might have missed.

“After Jay told me what Graham James did to him, I could not get it out of my mind, because so many things started to finally make sense as to why he was so angry,” Cindy says.

“I just got immersed in it for the entire two weeks. The story that they talk about with Sheldon Kennedy and Theo Fleury, that’s exactly what happened to Jay. The effects on their social behaviour — partying, anger, fighting, drug abuse, completely different social circles — were so similar, it was like, ‘Wow, Jay was, like, textbook to what happens when a teenage boy has some man mentally overpower him.'”

She says Macaulay was a normal teenage guy who was fiercely loyal to the people he could trust before he left for Swift Current. He had a great sense of humour and possessed an infectious laugh that made everyone smile.

“He had such a kind, caring soul to him when we first started dating that not a lot of people saw,” she says.

Cindy recalls how nervous Macaulay was about going to Swift Current and how exciting he thought it would be to make the team. Hockey was his ticket to a better life.

She remembers how troubled Macaulay’s relationship was with his father, making him a perfect target for James.

“Graham went after kids whose backgrounds didn’t have a solid foundation, and Jay didn’t have that,” she says.

“That monster sees that little bit of weakness in a good-looking teenage boy and preys on it. Jay was looking for someone to guide him, and his dad sure wasn’t going to.”

”That monster sees that little bit of weakness in a good-looking teenage boy and preys on it.”

When Macaulay left the Broncos the first time, he told Cindy that to play in the WHL he had to eat, sleep and breathe the game and he just wasn’t willing to be that dedicated. She knew that didn’t make sense, because hockey was something he loved to do and was really good at.

She says Macaulay felt pressure to return to the Broncos the next season. He hated disappointing people and Trosky, whom he deeply respected, had suggested giving it another chance.

When Macaulay returned home again and was acting even stranger than before — he was confused about life, much angrier and less emotionally available — Cindy says she wrote Trosky a letter asking for his assistance.

“I reached out to Mr. Trosky to say something is wrong with Jay and that he needs help. I asked if he could talk to Jay because he wouldn’t talk to me,” she says. “I really wanted Jay to get help because something just seemed off and I didn’t know exactly what it was.”

”I really wanted Jay to get help because something just seemed off and I didn’t know exactly what it was.”

Once Macaulay was finished with the WHL he was angrier and, eventually, as he began pushing away those closest to him, he started getting into serious drugs. He and Cindy would fight constantly and the arguments could turn physical. He was cheating on her, acting unpredictably and hanging out with people she didn’t know.

“We were experiencing the cycle of abuse at a very young age,” she says.

None of that was normal, she says, adding Macaulay once had strong morals and values and would often look down on people who turned to drugs and alcohol to have a good time.

The anger, the cheating, the abuse — suddenly it all made sense.

And, she thought, if that could happen to Macaulay — one of the strongest men she’s ever met — then it could happen to anybody.

“I remember thinking before, that ‘no way Jay would let that happen,'” she says. “But then you realize it’s not a physical thing — it’s power and control.”

●●●

Macaulay likens his life to a storybook; it plays out more as a horror movie.

His existence has been well-documented over the years. He has a long criminal record, with many newspaper clippings detailing brushes with the law.

Macaulay points to two starkly different photos in the local newspapers that best summarize his downfall.

The first is from March 1988. He and his teammates on the John Taylor Pipers are celebrating a 7-3 win over St. John’s-Ravenscourt to capture the Winnipeg High School Hockey League championship. In the other, Macaulay’s car is littered with bullet holes after police unloaded multiple rounds following a pursuit.

Macaulay says he was extremely drunk and had just robbed a pharmacy to feed his drug addiction.

“This was my life after Swift Current,” he says. “All it was for me was drugs and alcohol… for years this went on.”

Macaulay says there have been stretches where it wasn’t all bad; he even owned his own business at one time. But rarely would it last, his drug and alcohol addiction always the cause of his undoing.

He’s lost track of the number of times he’s gotten so high that he would just sit and stare at a wall, sometimes for weeks. He’s been in and out of jail for much of his adult life; he estimates that during a particularly rough period, from 2014 to 2017, he racked up at least 50 criminal charges.

“I’ve been a walking nightmare,” he says.

His most horrifying moments, though, came in 2014, shortly after his mother’s death. He was left a modest inheritance; he spent it all on drugs.

”What have I done to myself? What have I done to my family?”

Needing more cash to feed his opiate addiction, he decided to rob another pharmacy but got caught. His then-girlfriend was eight months pregnant with their child; because of his arrest, she was kicked out of their rental home.

“Now I’m sitting in jail, sweating from all the drugs coming out of me and it’s a horrible comedown like you wouldn’t believe,” he says. “I’m thinking, ‘What have I done to myself? What have I done to my family?’”

When he’s granted bail, he runs, breaks into another pharmacy and is placed back behind bars. When Macaulay gets out the next time, he becomes hooked on meth, only to return to prison a short time later.

“The thing is, my brain wasn’t focused enough to understand what I was doing to myself,” he says. “So every time I got out of jail or I got out on bail, I just wanted to go back to partying, back to my escape. It was a revolving door for me.”

For years, he was told by family members, friends and the police — including his older brother, Don, who was a high-ranking officer but is now retired — that he desperately needed professional help. He has been asked about his time in Swift Current, too, and whether James had tried anything with him.

But every time those questions arose, he refused to listen, instead falling deeper into the hole created by his drug abuse. For decades, Macaulay says, that was the only way he knew how to handle his problems.

It wasn’t until his most recent arrest, in 2017, for robbing another pharmacy, that he would finally seek the help he needed. This time Macaulay would be sentenced to more than two years to be served in a federal penitentiary.

It’s during this sentence that Macaulay was able to take back some control over his life and release himself from the grip drugs had on him. Through regular counselling, he now has a better understanding of how his brain works and why, for years, he worked hard to suppress his pain.

Macaulay completed his sentence early last month and is now focused on further healing his mind and body. He hopes to eventually get a job. However, his hope of going to the gym each day was quickly derailed by COVID-19 restrictions.

If he has any worry, it’s in securing a support system on the outside. While in prison he was able to regularly meet with a psychologist for his trauma but that won’t be readily available anymore. He hopes to make amends with his family but knows he has a ways to go before he can earn any trust back from the people he’s hurt.

“I still got a long road ahead of me and I can’t just sit here and be bitter at everybody because of what happened to me in Swift Current. I got to keep fighting,” he says. “But it’s like a wood tick on me, thinking could this have all been prevented?”

As for James? Granted full parole on Sept. 15, 2016, he has fulfilled the requirements of his last sentence, which expired in late 2019.

He is a free man, believed to be living in Montreal.

jeff.hamilton@freepress.mb.ca

Jeff Hamilton

Multimedia producer

Jeff Hamilton is a sports and investigative reporter. Jeff joined the Free Press newsroom in April 2015, and has been covering the local sports scene since graduating from Carleton University’s journalism program in 2012. Read more about Jeff.

Every piece of reporting Jeff produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, December 11, 2020 10:02 PM CST: Fixes typo.