Pandemic’s hidden pain Delaying, cancelling children's and elective adult surgeries has serious, sometimes lifelong, consequences for patients

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 27/11/2020 (1839 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Delayed medical procedures will hurt Manitobans for years after the COVID-19 pandemic ends, as painful ailments drive patients toward opioids and children outgrow the period for surgery to prevent lifelong problems.

In Manitoba, at least 5,300 surgeries were officially delayed in the spring, though some estimate the figure is likely closer to 12,000. The province is also the first in Canada to again postpone elective surgeries this fall.

Health professionals across the world are urging governments to mitigate the impact of these delayed surgeries, but are finding the second wave of the novel coronavirus has nearly monopolized the public’s attention.

“Surgery is a very serious microcosm of the impact on health care as a whole,” says Janet Martin, a Western University professor in London, Ont., who has advised global organizations on how to alleviate the harm from delayed care.

“The knock-on effects really do impact a large portion of our society.”

Overflowing funnel

Across the world, COVID-19 closed down operating rooms for about 12 weeks in the spring. Developing countries that closed their borders experienced shorter disruptions.

GlobalSurg, an international research project on the pandemic, estimates that the initial shutdowns cancelled or postponed 28 million surgical procedures, including almost 400,000 in Canada.

Martin, a professor specializing in anesthesia and epidemiology, notes that wealthier countries are less used to preparing and dealing with epidemics, and tend to schedule surgeries months in advance, leaving little wiggle room for disruptions.

Canada, particularly, has a problem of funnelling people into hospitals, leading to “bed blocking.” It’s often easier for doctors to send someone to a hospital than it is to adequately meet their needs through home care or a personal-care home.

When the pandemic hit, Manitoba followed most other developed countries in prioritizing essential and time-sensitive surgeries, especially those addressing cancer, cardiac issues and trauma.

“These slowdowns were needed to both mitigate further spread of the virus and to redeploy staff to other areas to assist with the rising number of hospitalizations involving COVID patients,” wrote a Shared Health spokesman.

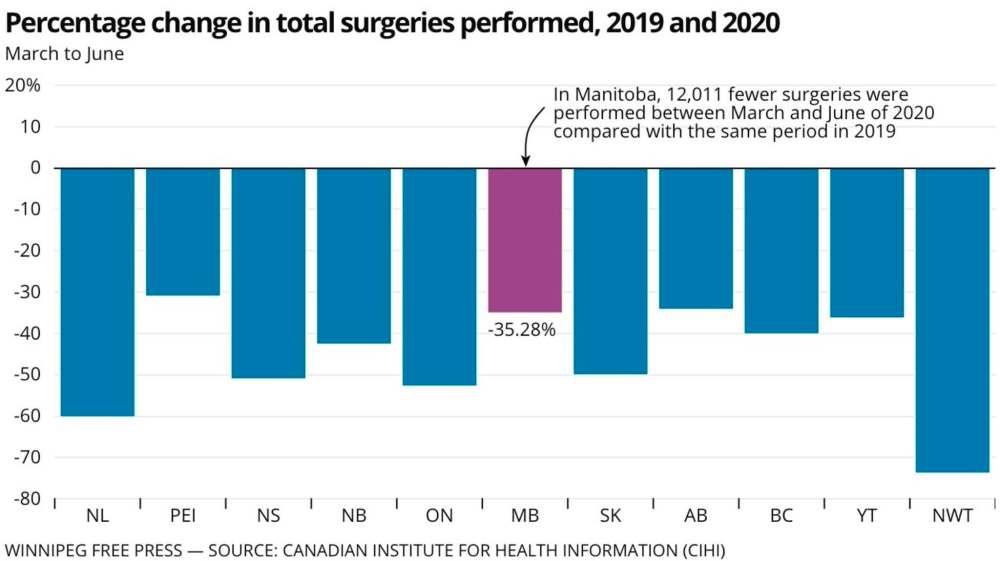

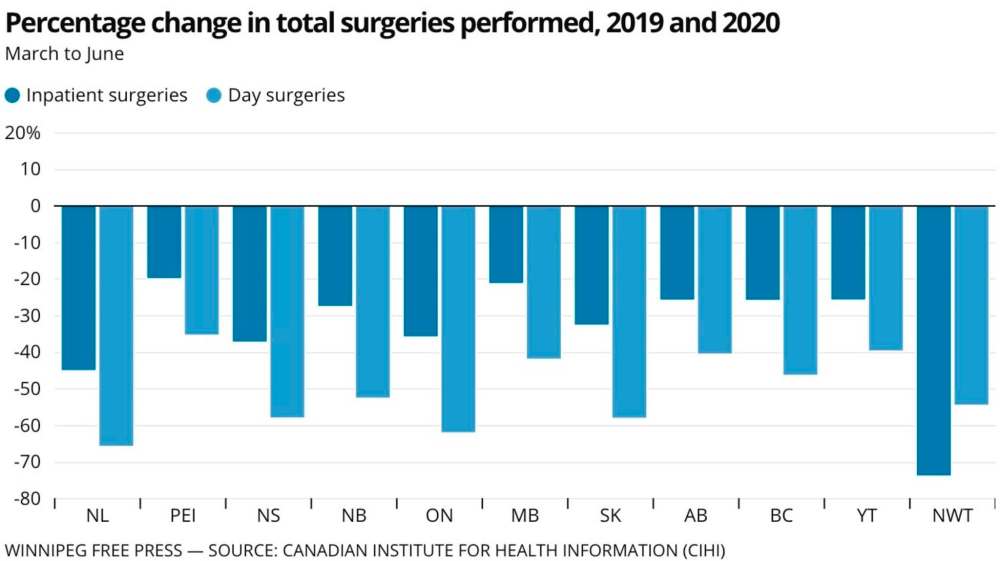

In an analysis of data provided by the Manitoba government, the Canadian Institute for Health Information found the province had 12,000 fewer surgeries between March and June of this year compared with the same time frame a year prior.

However, Shared Health said approximately 5,300 surgeries had been postponed within the Winnipeg health region, as well as the Health Sciences Centre’s services for those living outside the city. That excludes surgical facilities outside the Perimeter Highway, and the agency noted a 2019 boost in certain services due to extra funding could be inflating the CIHI number.

Manitoba initiated a second surgical slowdown on Oct. 26. As of Nov. 24, 968 non-urgent and elective surgeries were postponed, half of them involving orthopedics, head or neck surgeries or obstetrics and gynecology.

Yet that number does not reflect surgeries that were simply never scheduled because of the pandemic, Shared Health cautioned, adding that all data is hard to quantify, as some surgeries take multiples of more time than others.

“Given the current demands within critical care and medicine, and the ongoing high volumes of active COVID cases, normal surgical volumes will not be established within the next four weeks,” an agency spokesperson wrote Thursday.

Meanwhile, Winnipeg emergency-room visits dropped 11 per cent between March and October, compared with a year prior.

Winnipeggers generally avoided going to the ER for anything not life-threatening — there was a much lower drop in patients with the most severe needs, such as resuscitation or going into labour.

As a silver lining, general-practitioner data suggests a tenfold increase in virtual-care visits from a year prior, according to Health Department billings.

That meant Manitoba doctors were able to offer a similar number of appointments as last year, with a third of them occurring virtually during the pandemic.

Intractable backlogs

As part of the GlobalSurg project, Martin’s colleagues have published guidance on how to safely run hospitals in the pandemic, and how to catch up on backlogs.

A major challenge is COVID-19 itself. Patients carrying the virus, including people who do so unknowingly, have a higher risk of complications and death.

A month ago, Manitoba officials said one person who was aware they’d been in contact with someone experiencing symptoms showed up for a medical procedure anyway, putting an entire surgical team into self-isolation for two weeks.

Within the past two months, Shared Health implemented rapid testing for COVID-19 the day before a patient’s surgery. Before that, nurses went over a questionnaire with patients, who were tested only if they presented symptoms or risks of exposure to the virus.

Manitoba chief nursing officer Lanette Siragusa has urged patients not to fear going ahead with surgical procedures that have not been cancelled; their needs have been deemed a priority.

Looking solely at spring’s first wave, Martin’s colleagues at GlobalSurg looked at how Canada could catch up. They figured that ramping up the capacity to do surgeries by 20 per cent above the pre-pandemic baseline would take just over 10 months.

“We know is that a 20 per cent increase in capacity over baseline in the surgical setting is impossible, because we have too many bottlenecks which are very challenging to address,” Martin says.

That’s because backlogs can be fixed only if four criteria are filled: staffing, space (such as hospital beds), equipment such as PPE and drugs, and co-ordinated, efficient planning.

Few places have all of four at the same time, and yet provinces tried. Before the second wave, Manitoba said it managed to clear 300 of 5,300 postponed surgeries.

British Columbia managed to increase its capacity above the baseline from before the pandemic in an effort to catch up. But others, such as Ontario, have not been able to bounce back to their normal baseline.

Dr. Theresa Tam, Canada’s chief public-health officer, says she fears “significant long-term impacts” from postponed treatment and that she regularly discusses health-care capacity with the provinces.

But Ottawa doesn’t do central planning or offer guidance on prioritizing procedures, she says.

Martin says Canada can’t just find a cadre of extra surgeons, anesthesiologists and operation-room nurses to cut down backlogs.

“It’s out of our hands; we really don’t have an additional capacity,” she says. “When some of our basics go away, we have nowhere to turn.”

Lifelong impacts

As with everything related to the pandemic, society’s most vulnerable bear the brunt of surgical backlogs.

Children stand to be the most impacted, despite having some of the least severe outcomes from COVID-19.

That’s because many problems kids face can be fully solved only at particular points in their development.

“Children waiting for surgery in general hospitals may become lost in the large backlog of adult surgeries,” reads a recent commentary in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

The surgical heads of Canada’s children’s hospitals say children often need to get surgery in other provinces, raising questions about who gets prioritized.

“Children are not small adults and they are not less deserving. Children have unique surgical needs that require prioritization within our health system,” the doctors wrote.

As The Globe and Mail reported this month, two-thirds of children waiting for surgeries at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children have missed the “developmental window” that would have been most effective to fix conditions such as uneven legs and cleft palates.

Manitoba recorded a 32 per cent reduction in elective pediatric procedures between March and October of this year, compared with a year prior. The most commonly delayed procedures include tonsil surgery and draining ears to avoid infection, according to internal data.

In January, before the first COVID cases appeared, Winnipeg’s Children’s Hospital was already scaling back surgeries because of a nasty flu season.

Meanwhile, Martin warns that some adults with serious medical needs are included under the list of elective procedures.

People needing transplants or early cancer care can often be kept alive for months with treatments to manage failing organs, though this obviously affects their quality of life.

Despite including cancer surgeries among their priorities, provinces reported conducting one-third fewer of those operations in the spring compared with a year prior, though the drop was only nine per cent in Manitoba.

“The thing is, a number of cancers are slow-going enough, that they’re actually not urgent — but they can’t be non-urgent forever,” Martin says.

Some of the most painful problems are among those being pushed off for months, and that likely means more painkiller use.

Hip and knee replacements have been among the most commonly delayed procedures in Canada during the pandemic, along with procedures meant to alleviate intense pain, such as hysterectomies and repairing hernias and gallbladder issues.

“People need to have pain relief, and opioids may be, in some cases, the best option,” Martin says.

“It can put patients at risk of entering issues of dependence and abuse,” she says, pointing to particularly vulnerable patients who can’t currently access social programs or family support due to public-health orders.

How to cope

Before the pandemic, a University of Manitoba team set out to analyze the impact of cancelled and postponed surgeries.

In normal times, a delayed elective surgery increases pain, but also depression and anxiety.

Analyzing data Statistics Canada collected between 2005 and 2014, researchers found patients with delayed procedures reported “poorer physical health, increased functional impairments and worse psychological functioning,” and a heavier reliance on relatives and friends.

In a global pandemic, all those factors could get even worse.

“It’s really challenging to know what the scope of the problem will be, but I think we can anticipate that there will be additional challenges for patients,” says clinical psychologist Dr. Renée El-Gabalawy, a U of M professor.

“These challenges will outlive the pandemic.”

In a separate, ongoing study on Canadians’ mental health during the pandemic, she found the most vulnerable people tended to be more stressed about their regular appointments and medications than actually catching COVID-19.

“We may want to be thinking about additional resources and funding that may be needed to meet the demands relating to these backlogs, and make sure these patients are supported.” — Dr. Renée El-Gabalawy, clinical psychologist

El-Gabalawy says Manitobans need to bolster their mental and physical health by eating well, exercising, sleeping enough and limiting drinking and recreational drugs.

She recommends mindfulness and tapping the province’s mental-health program.

“More than ever, I think people need to take an active role in their health care right now and focus on aspects that are within their control,” she says.

“Unfortunately, they have no control over when they’ll get surgery, or their procedures and appointments. But they do have control on being able to maximize their health by focusing on those aspects.”

On a systemic basis, it will take an influx of cash to cut down wait lists when the pandemic ends. But El-Gabalawy says research suggests there are positive spinoffs when people get the care they need.

“We may want to be thinking about additional resources and funding that may be needed to meet the demands relating to these backlogs, and make sure these patients are supported,” she says.

What can help right now is getting the coronavirus under control.

Martin is alarmed by Manitoba’s persistently high case numbers, and she hopes people heed public-health rules.

“COVID circulating in the community directly has an impact on our ability to provide life-saving, life-giving surgery,” she says.

“There are people right now who don’t know they’ll need a surgery during peak-COVID. And gosh, I hope the system is there for them when they need it.”

dylan.robertson@freepress.mb.ca

History

Updated on Friday, November 27, 2020 7:06 PM CST: updates bg photo

Updated on Friday, November 27, 2020 7:08 PM CST: Updates background photo

Updated on Friday, November 27, 2020 7:22 PM CST: Removes corrupt image.

Updated on Friday, November 27, 2020 10:07 PM CST: Adds new background photo