Labour, delivery, distrust Ending a decades-old practice flagging high-risk – mostly Indigenous – births hasn't stopped painful hospital-ward newborn apprehensions

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 27/11/2020 (1840 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Nearly five months after Manitoba ended the practice of reflexively deploying child-welfare agents to maternity wards, newborns are still being taken from their mothers’ hospital beds and placed into foster care.

The province officially ended birth alerts July 1, and the number of newborn apprehensions is decreasing. But Manitoba isn’t tracking whether foster agencies are following new rules to ramp up contact with high-risk mothers before their babies are delivered.

Advocates say that will only delay the separation of children from their families, instead of preventing apprehensions.

“What’s important here is the work that is being done with parents pre- and post-birth, and the resources that are available,” says Daphne Penrose, the Manitoba Advocate for Children and Youth. “What are the checks and balances to make sure that’s happening?”

Manitoba leads the country in the proportion of kids in care, and they are overwhelmingly Indigenous. Social workers say it’s the result of decades of policies that set up First Nations families to fail.

Meanwhile, internal records show the Pallister government’s decision to end birth alerts was fuelled by pressure from Ottawa and a national uproar surrounding a video that went viral showing a newborn being taken away from a Winnipeg mother.

Hiding in the shadows

A birth alert is a form that social-service agencies fax to the Manitoba Health Department when they feel a pregnant mother is high-risk. Hospital staff are instructed to notify child-welfare agencies when the mother is admitted to a labour and delivery ward.

Not all birth alerts lead to apprehension; social workers are supposed to assess whether the newborn is headed for a safe home or needs to be put in the province’s care.

Penrose, whose role is to act as an arm’s-length inspector of Child and Family Services, says birth alerts date back at least two decades.

The original purpose, she says, was to prevent kids from going to homes where registered sex offenders lived, or when parents had cognitive issues that put the child’s safety at risk.

“How the practice has been used seems to have evolved or changed over the years,” she says.

“The birth alert is just a piece of paper and a process. It does not and should not guide social work.”

“The birth alert is just a piece of paper and a process. It does not and should not guide social work.” – Daphne Penrose, the Manitoba Advocate for Children and Youth

Everyone following Manitoba’s CFS system agrees that children whose parents put their well-being at risk should be placed in a safer environment.

Yet advocates have complained for years that birth alerts are no longer being used as helpful reminders for agencies to work with families to ensure babies have a safe start in life.

Instead, apprehensions increasingly appear related to issues such as poverty, though the province has studied the reasons listed on birth-alert forms for a single month. The analysis found substance and domestic abuse as the most common concern, though unstable housing was often cited.

Media have interviewed pregnant mothers in Winnipeg with prior involvement in CFS who intentionally avoid any contact with the health-care system and instead plan covert home births, putting their health and that of their babies at higher risk in order to avoid another apprehension.

Those anecdotes seem to align with Manitoba health data analyzed last year in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Between 1998 and 2015, women who had a newborn taken away tended to not participate in prenatal care in subsequent pregnancies including ultrasounds and weight checks, which can spot emerging problems for both mother and child.

Meanwhile, an exhaustive review of all published research on birth alerts in Canada released in February by University of Toronto professors found no conclusive evidence on whether they help or harm children.

Hundreds of newborns removed

In 2015, the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs hired a grassroots advocate, Cora Morgan, to help First Nations families constantly reporting issues with CFS agents.

A few months into the job, a pregnant woman asked Morgan to visit her maternity room in the former Women’s Hospital at Winnipeg’s Health Sciences Centre.

“That memory will be burned into my brain forever; it was the most horrifying thing I’d ever witnessed,” says Morgan.

The pregnant woman was living on welfare, and had planned to take her baby to her cramped rooming house, which the agency deemed an unsuitable living situation.

“This mom had nothing in the world, but put together a little bag of second-hand clothes and a few diapers,” Morgan says, recalling the CFS worker standing in the corner, tapping his foot impatiently.

“The mom couldn’t see because she was crying so hard, trying to change her baby’s diaper and getting him ready to be taken away.”

Morgan remembers the baby staring at her when social workers put the child seat on the sidewalk while opened the CFS worker’s car door.

“It was just overwhelming to me; I couldn’t understand how this was happening in our world,” she says.

It was far more common than she expected.

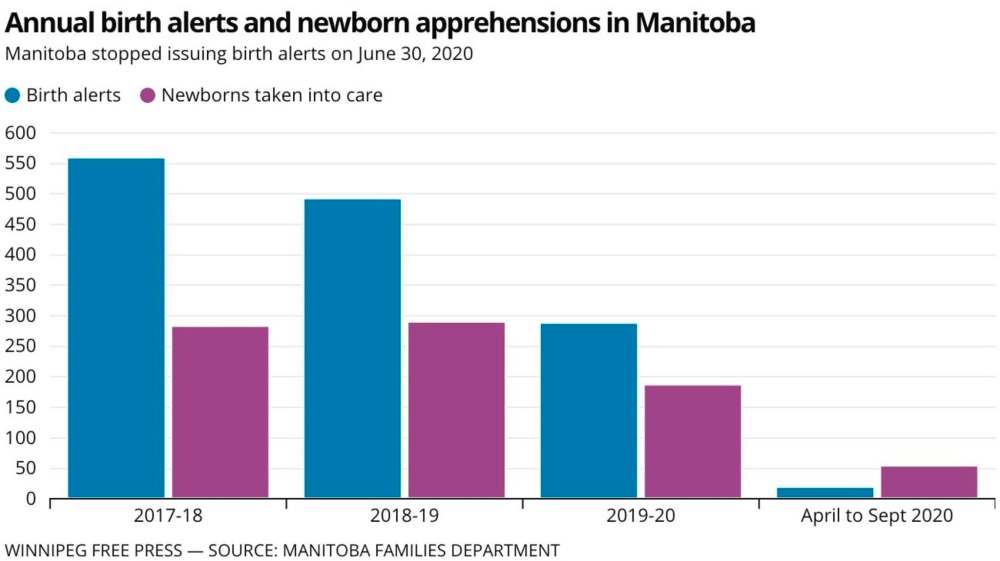

Internal data shows the province issued 558 birth alerts in the 12 months ending in March 2018.

During that time, 282 children were taken into foster care within the first three days of their life. (The province does not correlate how many of those apprehensions originated with a birth alert).

In Saskatchewan, just 157 birth alerts were issued during the 2018 calendar year despite an only slightly smaller population.

Manitoba data doesn’t include ethnicity on birth-alert forms, but the province believes it’s mostly the First Nations and Métis agencies who are being called to maternity wards.

“Indigenous families, who are overrepresented in child welfare, are disproportionately affected by the practice of birth alerts,” a provincial spokeswoman wrote.

The National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls called for “an immediate end to the practice” of birth alerts in its June 2019 final report.

It said birth alerts are part of the continuum of residential schools and the ‘60s Scoop, the mass apprehension of Indigenous children and placement in white families.

“Systemic racism, to me, is the most potent when it’s perpetrated by state governments,” says Cindy Blackstock, a longtime activist and social worker. “They’re interested in reform everywhere except within themselves.”

Manitoba data suggests the number of birth alerts and newborn apprehensions have both declined over the past two years, though Manitoba started recording specific data only in 2017 amid mounting political pressure.

It’s no coincidence that as of last March, 89 per cent of Manitoba children in foster care were Indigenous.

In 2016, a federal tribunal ruled that Ottawa had racially discriminated against First Nations children for decades by underfunding child welfare as well as the numerous supports that could prevent kids from being taken from their homes.

“The issues that drive the over-representation of First Nations kids in care are poverty, poor housing, caregiver substance abuse and multigenerational trauma, whether from residential schools or other forms of colonialism,” says Blackstock, executive director of First Nations Child and Family Caring Society, which filed the decade-long tribunal case.

“You have all these inequitable services going to the people who have been, arguably, the most disadvantaged by the Canadian government, which means that they’re more likely to experience family hardship (at which point) there are very few services to be able to react to that crisis.”

For decades, the federal and Manitoba governments both funded CFS agencies based on how many children were taken into care, leaving little room for training and grants that would help prevent taking a child out of the home in the first place.

It wasn’t until 2018 that Ottawa removed an economic incentive for child-welfare agencies on reserves to take kids out of their family homes. Manitoba had a similar funding model until 2019.

Both were the result of Blackstock’s tribunal case, as was the Trudeau government’s decision to introduce a national child-welfare standard that took effect last January. It requires provinces to have CFS agents make every effort to keep kids with relatives, if not their own parents, to maintain cultural ties.

But the MMIWG inquiry said those reforms will work only if families have access to things such as classes, child care and mentoring, both in Canada’s inner cities and on remote reserves.

Otherwise, families can’t support themselves, and many will repeat the trauma passed down from relatives who attended residential schools.

Morgan argues that ending birth alerts without those supports just means kids get taken into the system further down the road.

“Sometimes parents, mothers, need supports and those supports don’t exist — and there is no mechanism in place to do things in a better way,” she says.

‘Shooting from the hip’

The province ended birth alerts on July 1, after the COVID-19 pandemic delayed an original plan to do so in April.

Both the initial announcement and the delay came out of the blue for Indigenous leaders and child-welfare advocates. Families Minister Heather Stefanson told media she made the call after her department found a lack of evidence for continuing the practice.

In fact, there seems to be a lack of data or analysis from within Stefanson’s department. Instead, scores of pages of departmental correspondence and briefing notes for the minister, obtained in freedom-of-information requests, show a focus on external pressures.

Stefanson’s briefings point to the MMIWG inquiry’s criticism and demand to end birth alerts, and the looming 2020 national standard that requires provinces to prevent apprehensions at birth.

The Pallister government’s child-welfare legislative review committee asked for birth alerts to end in its September 2018 report, but that gets scant mention in Stefanson’s briefing notes.

Instead, the records touch numerous times on the January 2019 viral video of a baby girl being taken away from her mother in a St. Boniface Hospital room. The livestreamed video received more than a million viewers on Facebook.

A court later heard the mother had tested positive for oxycodone use during the pregnancy and had been previously investigated for possible abuse of her older children. The child was returned home 10 weeks later.

In terms of actual analysis, the department pointed to the CMAJ analysis on Manitoba mothers avoiding prenatal services.

The department also assembled a snapshot of birth alerts issued during a single month in 2018. The analysis does not say which month it studied, but noted there were 48 alerts issued.

The vast majority of those forms indicated substance abuse, while half of them claimed the parents had documented problems raising older children. One-quarter listed concerns about domestic abuse, mental health or “transiency.”

Of the 48 alerts, six children were not born in Manitoba hospitals (either due to moving outside the province, aborting, miscarriage or a home birth). Among the remaining 42, agencies had planned to apprehend 10 newborns, but ended up taking 24 children out of their families, and all but one were permanently placed in foster care within two years.

That appears to be the only analysis the province undertook to learn how many birth alerts are issued, and for what reasons.

Blackstock says governments tend to respond only to child-welfare issues under pressure from media scrutiny and sensational videos. She notes that Canada is among the few industrialized countries with no national tracking of children in care.

“What that means is that leadership are too often relying on kind of public opinion and media coverage of often the most egregious cases, and not the most typical cases that come to the attention of child-welfare, to guide their decision-making,” she says.

“Children deserve us to be making interventions that will actually work for them, versus shooting from the hip.”

Blackstock points out that some jurisdictions in Ontario have cut down on child apprehensions, but saw little change in the death rates of children in foster care.

“Solving the birth-alert issue isn’t solving child-welfare issues; we need to get at those underlying factors,” she says.

Supports questioned

Stefanson agrees, telling the Free Press the best way to cut down on birth alerts is to fund programs run by local communities. The government lists dozens of the programs it funds, with many run by Indigenous groups in the areas of Winnipeg and the province that have high apprehension rates.

Last fall, the province launched a doula project with the help of donors and private investors that provides an individual mentor to 200 Indigenous mothers considered at high risk of having their children taken away. The program is available only in Winnipeg.

In January, the province funded a new drop-in service in the North End called Granny’s House, which takes care of children so mothers can do errands or attend classes.

Officials figure this up-front programming will end up saving the province from costly foster-care cases.

“What we want to do is keep families together,” Stefanson says, declining to offer an opinion on whether there are sufficient supports in place.

“I’m confident that we’re moving in the right direction… and I think we will see more positive results, as a result of working closely with community-based partners.”

Penrose says the province needs to assess whether there are enough support programs, and that they’re available wherever families need them.

“It is critically important to the safety of children that these resources be in place, so that families that need them can rely on them,” she says.

Morgan argues the current range of programs are clearly inadequate.

“If they were that effective then we wouldn’t have this issue,” she says.

Hospital apprehensions continue

According to the province, the key to ending bedside apprehensions is repeated pre-birth contact between expectant mothers and CFS agencies.

The agencies are supposed to craft a “birth plan,” such as which relative or close friend could look after the child if the mother was deemed unsuitable, or needed to first take parenting classes.

Agents are supposed to assess those alternative options, including running background checks on relatives. Ideally, the parents can resolve addictions issues or take classes before the birth, so the baby can stay in the home or have another family member provide care for the first few weeks.

Until last spring, CFS agents simply had to make one attempt at contacting a pregnant woman deemed high-risk and file a birth alert if she refused help.

“Systemic racism, to me, is the most potent when it’s perpetrated by state governments. They’re interested in reform everywhere except within themselves.” – Activist Cindy Blackstock

Now, agents are supposed to make “repeated attempts to engage with family during pregnancy to asses risk, develop (a birth) plan,” reads an internal slide show from the Families Department.

Medical staff are supposed to phone CFS workers if they suspect safety is at risk, such as the potential of a baby going through withdrawal, or the mother is under the age of 18.

There were 45 such referrals in July and August; it’s unknown how many resulted in apprehension.

The province believes that between July and September, 22 babies were taken into care within the first three days of their life, though it’s still verifying that data with CFS agencies. That’s down from 31 newborns apprehended between April and June.

Meanwhile, the department logged 50 cases of high-risk pregnant women receiving CFS support to try keeping the baby in the family in July and August, up from 39 cases in the same period in 2019.

The department recorded another 80 families voluntarily accessing these services this fall, from September until now.

“The province continues to work closely with agencies and authorities related to the end of the use of birth alerts,” a Families spokesperson wrote.

“This includes monitoring the number of referrals from health-care facilities as well as the number of voluntary files opened with expectant parents.”

“Because they made this announcement that they’re ending the practice, it gave women this false sense of not believing that their baby could be taken.” – Cora Morgan

So far, 130 families have sought help from that voluntary service, which connects them with supports.

Yet the Pallister government has set no target for the percentage of mothers who should have a birth plan, or how many contacts agents should have with women before they go into labour.

“An exact number of contacts isn’t specified, because that may depend on each family’s situation,” a spokesperson wrote.

Stefanson said her only goal is a reduction in children being taken away from their families.

“We obviously want to focus on keeping families together, and reducing the number of children in care,” she says.

Stefanson notes that the numbers show a steady decline in children removed from their families. “I’m confident that we’re moving in the right direction,” she says.

But Morgan says the system isn’t operating as it should.

Her staff were called to 10 births in July and August where CFS agents were ready to apprehend babies, and another three in September and October.

Of those 13, five were taken into care. She says that’s likely just the tip of an iceberg that includes only mothers familiar with her office.

“Because they made this announcement that they’re ending the practice, it gave women this false sense of not believing that their baby could be taken,” says Morgan.

“There wasn’t planning in place so that the agency could select family homes.”

Stefanson says she hopes families and activists file formal reports if they’re not contacted by CFS agents before giving birth.

“We obviously are concerned with any situation like that,” she says.

“There are a number of initiatives that we are working in conjunction with (the) community on, to prevent those very issues from happening.”

Morgan says she has no clue what’s happening now, because code-red restrictions prevent advocates from visiting hospital wards.

Penrose says she’ll soon be asking the province how it assesses prevention work and infant safety, and whether agencies have ramped up pre-birth planning.

“The thing that’s most important is making sure workers are developing relationships with families… and identifying risk factors and helping parents to mitigate those risk factors,” she says.

“There are so many workers (and) so many families across such a broad geographical area, there is too much room for error if those processes, and a clear articulation of what is to happen, are not in place.”

dylan.robertson@freepress.mb.ca

Excerpts from freedom-of-information requests on birth alerts