Portage residential school named national historic site; First Nation plans museum

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 01/09/2020 (1644 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

A former Manitoba residential school has been deemed a national historic site, which local First Nations plan to use to educate the world about the system’s impact on generations of Indigenous children.

“The story needs to be told through Indigenous eyes,” said Chief Dennis Meeches of Long Plain First Nation.

He was speaking Tuesday, moments before Parks Canada deemed the Portage la Prairie Indian Residential School a national historic site, along with a similar site in Nova Scotia, called Shubenacadie.

The federal agency has also designated residential schools a “national historical event,” joining a list of hundreds that includes the 1919 General Strike and the construction of the Hudson Bay Railway to Churchill.

The commemoration responds to part of the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s calls to action.

The federal government separated at least 150,000 First Nations, Inuit and Métis children from their families, starting in the late 1800s, putting them in schools often run by various churches, in which abuse was commonplace. Children learned little curriculum and often lost their language and cultural ties, sparking intergenerational trauma.

Sir John A. looms over commemoration

The recent toppling of a Montreal statue of Sir John A. Macdonald, Canada’s first prime minister, loomed over Tuesday’s designation of two residential schools as historical sites.

The recent toppling of a Montreal statue of Sir John A. Macdonald, Canada’s first prime minister, loomed over Tuesday’s designation of two residential schools as historical sites.

“Historical accuracy (and) truth-telling require the establishment of new memorials — just as much as it requires us to question those that we have celebrated in our past,” said Ry Moran, director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation.

His comments during a Tuesday ceremony in Winnipeg came days after Montreal protesters pulled down a bronze, century-old statue of Macdonald.

Though hailed as a father of Confederation, Macdonald also helped establish residential schools and ordered the execution of Louis Riel, the Métis leader who founded Manitoba.

At a Tuesday ceremony in the RBC Convention Centre, Chief Dennis Meeches of Long Plain First Nation noted Macdonald’s disregard for Indigenous people “has seeped into the consciousness of the nation, generation after generation.”

Moran said statues to people such as Macdonald need more context than just their accomplishments, in order for people to understand history.

“When it comes to understanding someone like Sir John A. Macdonald, it is insufficient to tell his story only through the eyes of the colonizer,” he said in an interview.

“Those racist ideas and underpinnings of our country are what prevent us from reaching our full potential, and reaching a society that is truly embracing the full spectrum of human rights.”

— Dylan Robertson

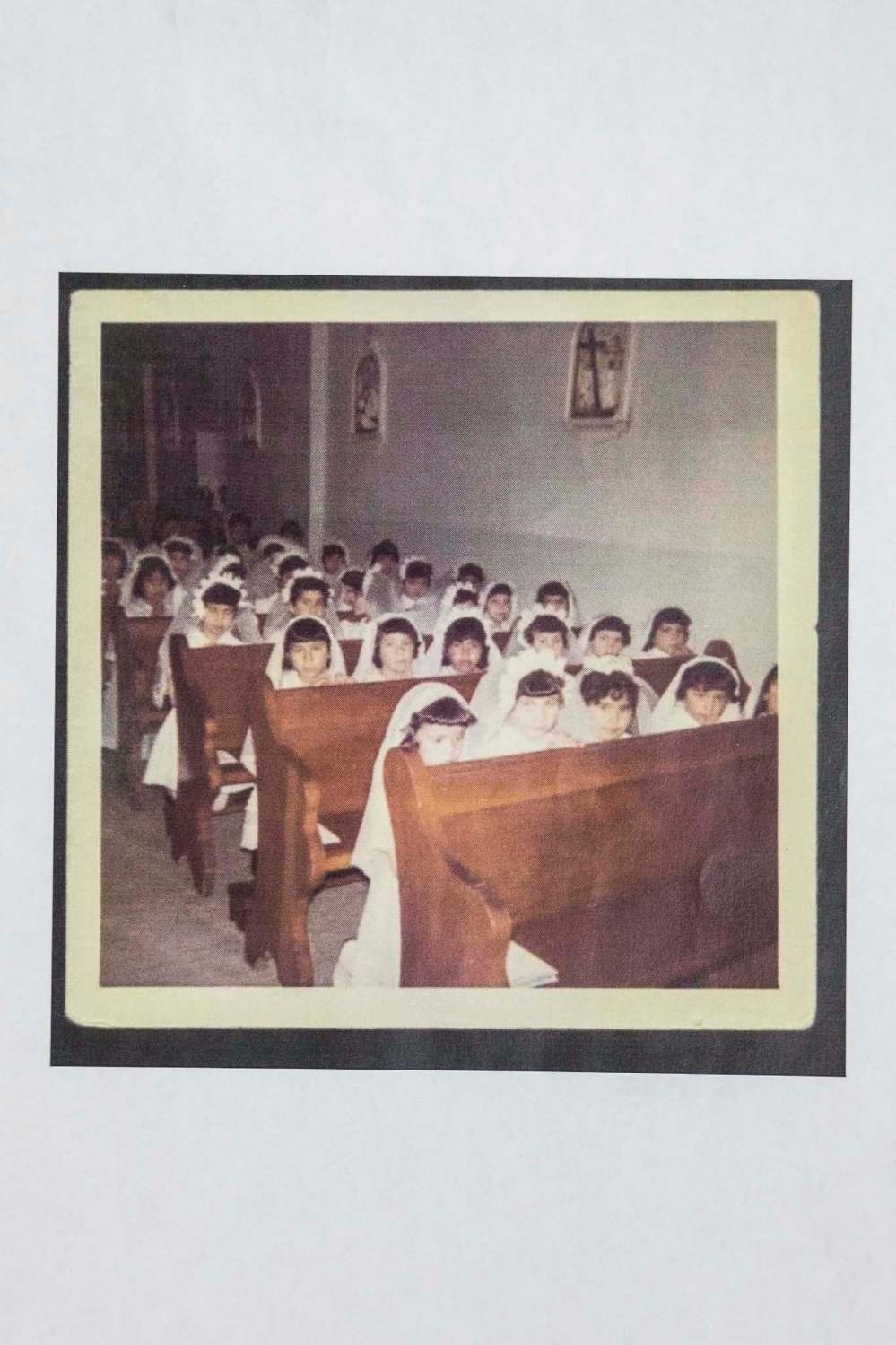

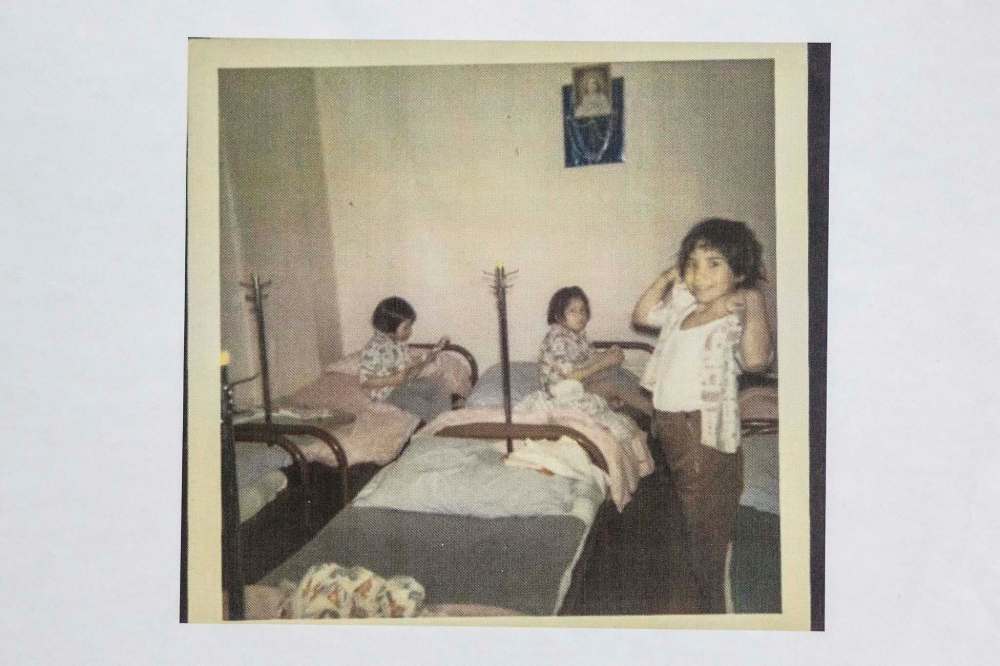

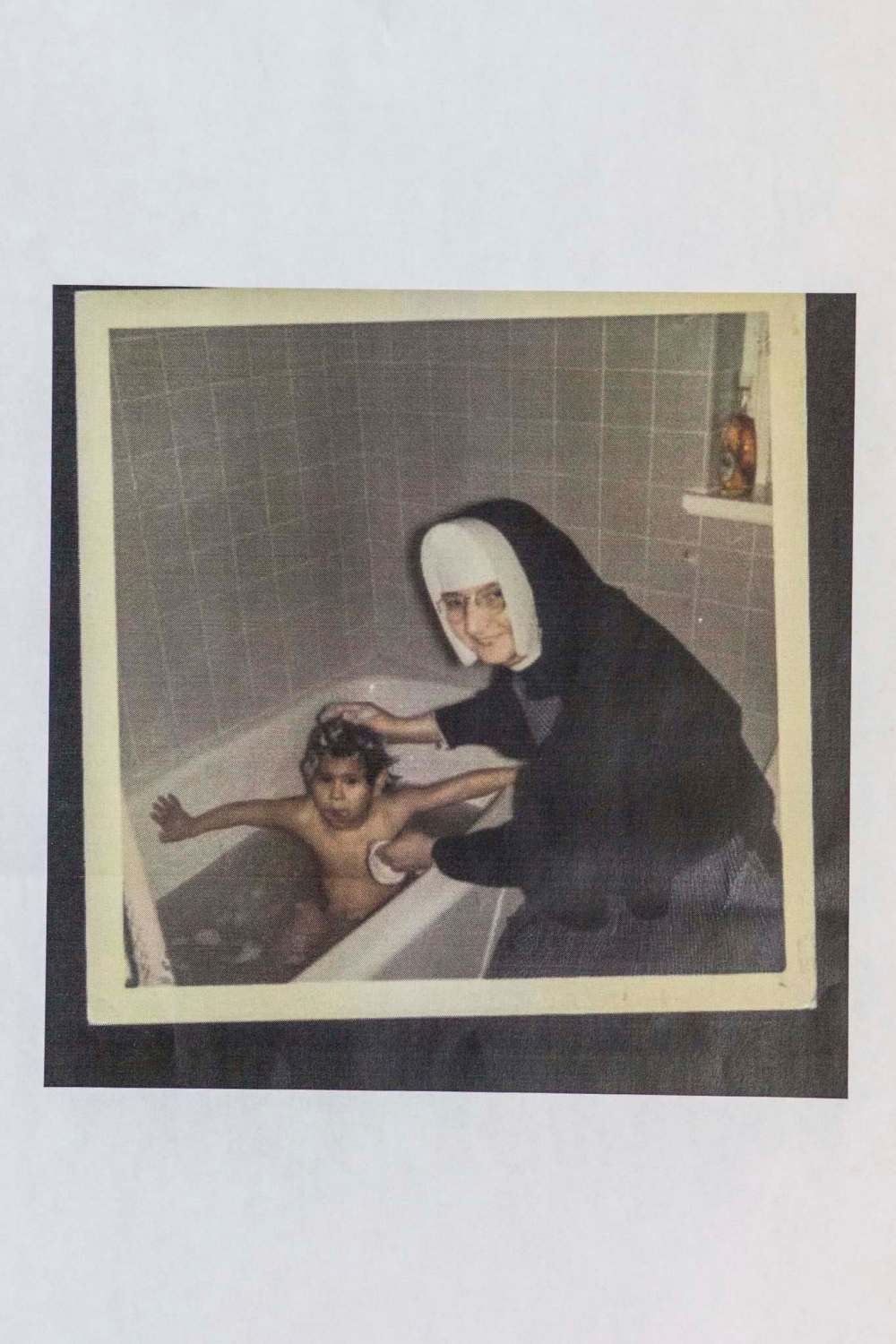

Children from numerous First Nations in Manitoba were sent to the school in Portage la Prairie, some 70 kilometres west of Winnipeg, where they endured harsh labour, horrific abuse and isolation from their families, according to testimony and national records.

Meeches’ own mother attended the school, and tried running away from the abuse, only to have her head shaved to serve as an example for others, he said. His uncle recalls being left outside while sick with pneumonia. He recovered, and eventually fought in the Canadian army.

The school houses deep scars for hundreds of Manitoba families, Meeches said during a Tuesday ceremony at the RBC Convention Centre, which was livestreamed across Canada.

The building in Portage has a provincial designation, with a plaque explaining the building’s use but little of what went on inside.

Ry Moran, director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, said there are scores of sites in Manitoba that most people don’t know about. One former residential school sits in Winnipeg’s River Heights neighbourhood.

“Most Winnipeggers aren’t even aware that it exists, and it’s located in one of the most affluent neighbourhoods of the city. That’s the insidiousness of the erasure that has happened in this society.”

The NCTR lists a registry of residential schools, with photos and testimonies from survivors. It also tries to track hundreds of unmarked cemeteries where children were buried.

“The buildings are but a shell; it is the stories of the children and people who attended these schools that are so important,” Moran said.

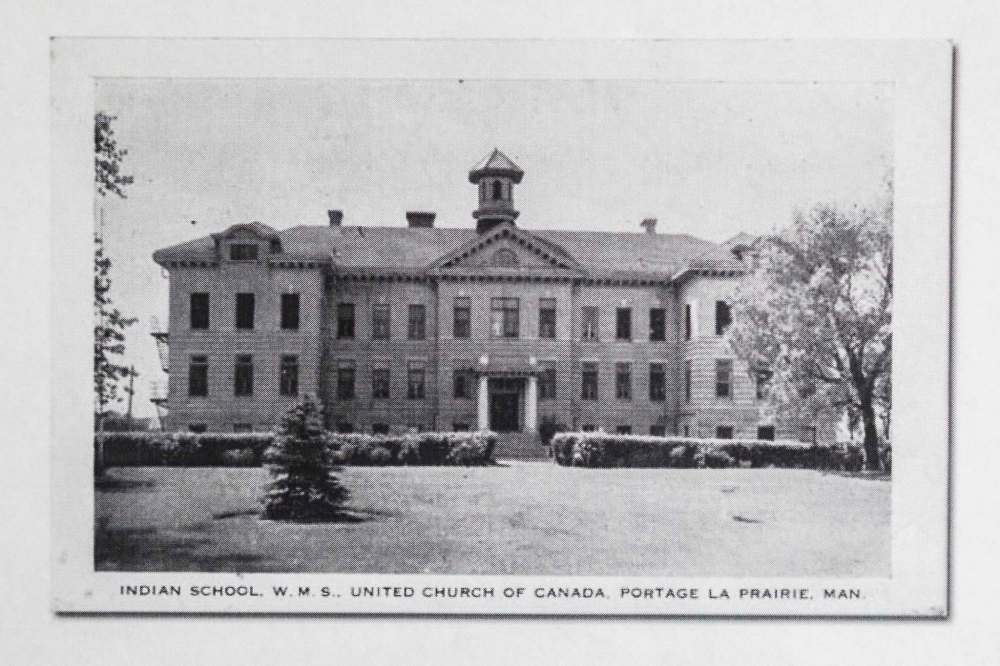

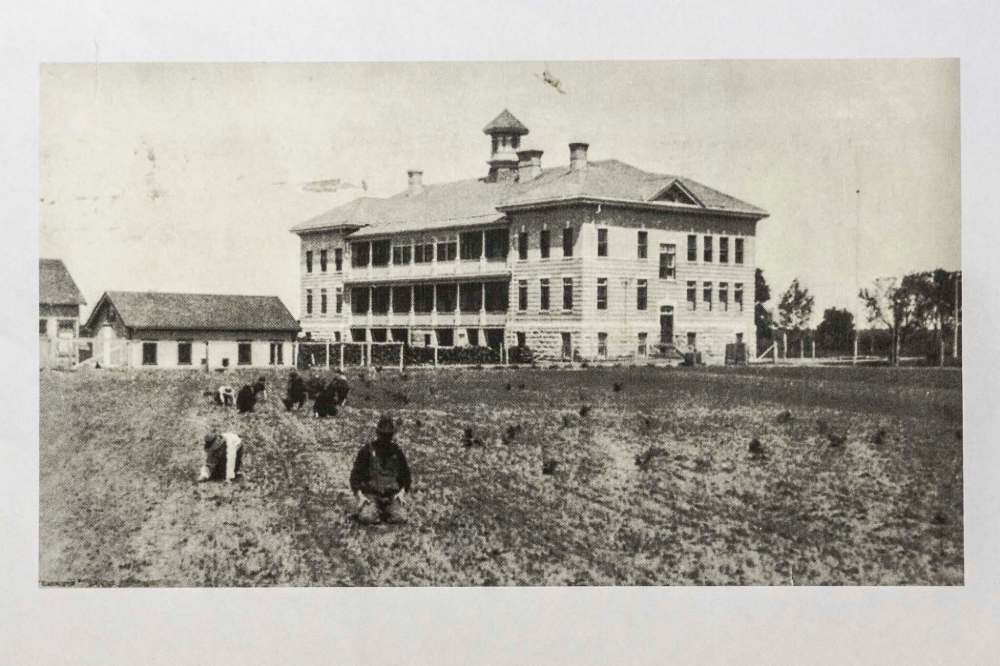

The building designated Tuesday in Portage opened in 1915, though the school operated at another site just east of the town for years, established in 1888.

The school ran under United, Presbyterian and federal leadership, operating as a residential school until 1960 and then a student residence until 1975.

Meeches said his band has operated tours through the building, but wants to make it a proper residential-school museum, library and memorial garden. That’s why the First Nation nominated the school for the Parks Canada designation.

“We are very honoured to host a national historical site, basically in the centre of Canada, and to work towards highlighting and educating, and bringing awareness about these schools to the world,” Meeches said.

Long Plain acquired the derelict school building in 1981, as part of its treaty-land quota, and installed a college that has since moved to Winnipeg.

“There’s a lot of scars in that (building), but I think it’s made us stronger and more resilient,” Meeches said.

“We’re recognizing Canada’s efforts to reconcile with Indigenous people. Although sometimes they get it wrong, today is an important milestone, and a recognition of what happened.”

Parks Canada says the three-storey brick building is “a rare, surviving example” of residential schools. It says the imposing shape and size in an isolated space “generated feelings of dislocation, intimidation and fear in the Indigenous children who lived there,” who were raised in open-air environments.

dylan.robertson@freepress.mb.ca

History

Updated on Tuesday, September 1, 2020 10:07 PM CDT: Fixes spelling of neighbourhoods