The cost of hoarding Pandemic panic buying has pushed Canadians' food waste bill to $2,000 annually per household

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 01/09/2020 (1929 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Canadian households are paying an annual $2,000 “invisible bill” in food waste, boosted this year by $238 because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

And research suggests that invoice isn’t going away anytime soon.

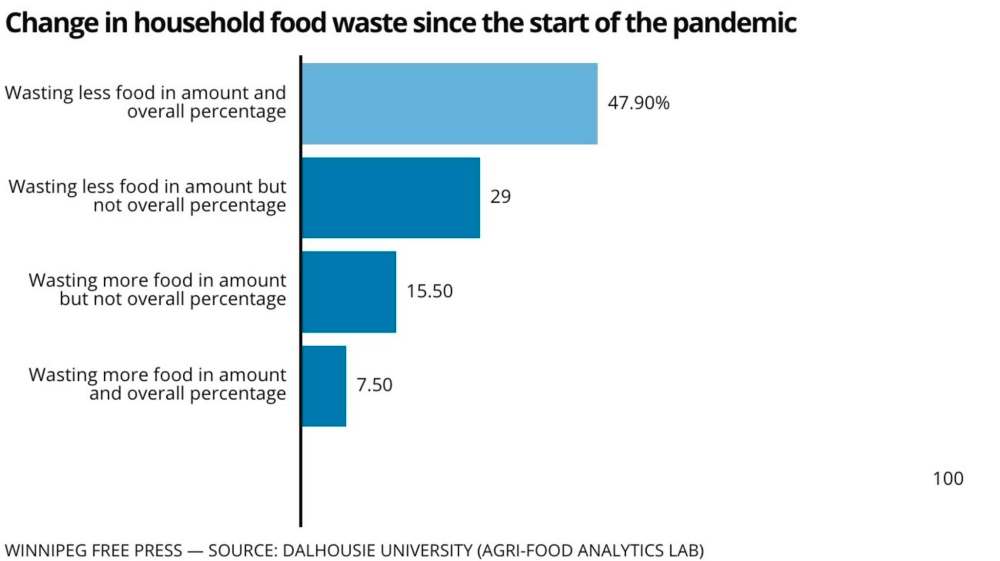

Households across the country are tossing up to 13.5 per cent more food than before the pandemic, according to a new study by Dalhousie University’s Agri-Food Analytics Lab that surveyed over 8,000 Canadians in August.

That’s roughly five pounds of food per week for every house in the country — totalling about 20- to 24 million kilograms of additional organic waste per month and an annual increase of at least $238 per household for all of Canada. That’s on top of the $1,766 annual avoidable food waste per household, pre-pandemic.

“A lot of it comes from the anxiety produced by the pandemic that’s shifted, changed and created all these different food consumption trends,” says food supply chain expert Sylvain Charlebois, who conducted the study.

“When COVID-19 hit, environment consciousness and personal finances sort of took a backseat,” he said. “People went out panic buying and costs or how their waste increase would affect the planet didn’t matter because there was this scarier thing to worry about.”

Prior to March, around 40 per cent of every dollar spent on food went towards dining out, according to Statistics Canada. Amid shutdowns across the country, that number fell well below 10 per cent — which Charlebois believes added to rising residential waste during the pandemic.

“It all shifted when people had to start making more food at home than they were used to,” he said. “That meant more erratic grocery-buying habits and eventually more waste.”

“General fear is also shockingly quite a big factor”

– Sylvain Charlebois, food supply chain expert

WM, North America’s largest privately-run waste management provider, told the Free Press that “shift” in eating at home versus eating out might also be why they saw a rapid change in their commercial versus residential garbage disposal services.

“We’ve definitely seen a major increase for waste management required in our residential client base compared to our commercial clientele as a result of the pandemic,” said Rina Blacklaws, WM’s spokesperson for Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. “Our collection, disposal and recycling for Canada and the U.S. switched gears because of the pandemic. And while those trends appear to be stabilizing as commercial operations are opening up, it’ll take a while before that changes back to normal.”

But apart from not dining out, there’s several other reasons for why people might be wasting more food.

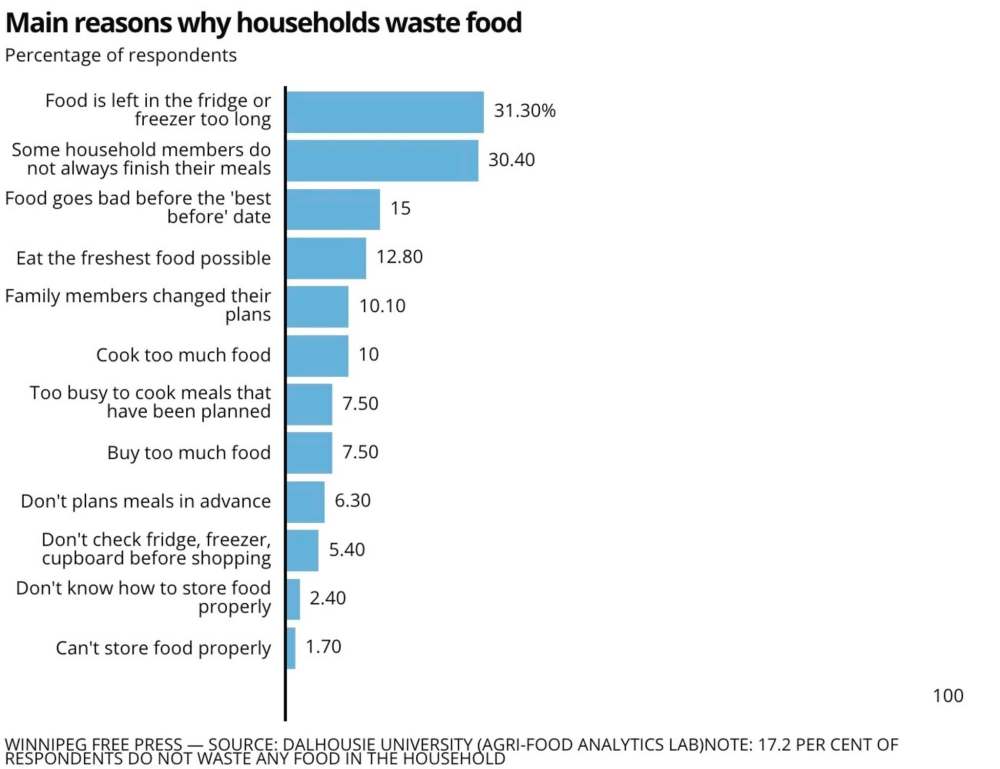

The study suggests some of it is because of poor planning behaviours (31.3 per cent of respondents), or not consuming food before best-before dates (15 per cent of respondents). Other reasons include household members not finishing their meals (30.4 per cent of respondents) or “preferring the freshest possible food” (12.8 per cent).

“General fear is also shockingly quite a big factor,” said Charlebois, citing one in 10 respondents who said they’ve thrown away food thinking it was contaminated by COVID-19 — with that number highest in Quebec (14 per cent) and British Columbia (13 per cent).

Despite disposing more groceries and food from home, however, Charlebois says the lack of commerical waste means that Canadians are producing less waste overall.

And according to the study, respondents are trying various eating habits — newly developed since previous years — to produce less waste from their food: about 34.5 per cent said they’re eating more leftovers; 22.5 per cent are canning, freezing or preserving food more often; and in Manitoba, more than 20 per cent people said they’re eating more food past its expiration date.

“One easy way to produce less waste though is by considerating donating what you can instead of buying in excess then wasting it,” said Meaghan Erbus of Winnipeg Harvest.

Erbus said she’s seen more people access their Winnipeg Avenue food bank than ever before, but “inventory continues to go downhill.”

“Give back instead of wasting.”

Currently, the City of Winnipeg does not track food waste in its garbage collection. But in a statement made Tuesday, communications officer Adam Campbell said they’re beginning a pilot program for residential food waste collection in select neighbourhoods next month.

“The pilot will divert food waste from the landfill and turn it into compost at the Brady Road Resource Management Facility,” reads the statement. “The pilot will help us determine how to collect food waste from all homes in Winnipeg and if residents feel it is valuable.”

Twitter: @temurdur

Temur.Durrani@freepress.mb.ca

History

Updated on Tuesday, September 1, 2020 7:55 PM CDT: Fixes quote at end of story.