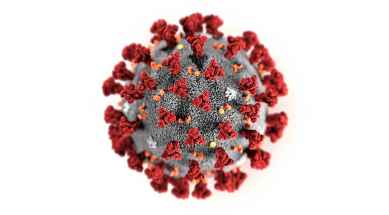

Fear and loathing Coronavirus symptoms include running nose, headache and fever... and can lead to misinformation, hysteria and bigotry

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 06/02/2020 (2134 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

To understand what a culture most fears, it is sometimes useful to look at its visions of horror. The scary tales told at night around fires, or in dog-eared paperbacks, or even on movie screens populated by D-list actors: all of these can give a hint to the anxieties that hiss the loudest in the mass public psyche.

Among the best examples of this is the ongoing evolution, and unending popularity, of zombies.

In the early days of zombie pop culture, the archetypical living dead was most often moved by supernatural forces. The word “zombie” itself entered the English lexicon from the Haitian vodou tradition, where the myth arose during centuries of suffering under French enslavement; Haitians knew far too well the restlessness of cruel deaths.

Through the 20th century, as zombies gained a firm foothold in North American culture, different origin stories arose. For awhile, it was in vogue that they were scientific experiments gone wrong, their reanimation brokered by a mixture of machines and madness, as an anxious public wrestled with the rise of technology it did not understand.

But years and history turned, and even as modern technology grew more powerful, it also became more accessible, less mysterious; the public no longer feared what scientists could do. It was then that the zombie archetype settled into its current form: today, the cause of a zombie infestation is almost invariably biological.

A virus. A bacteria. A fungus. Something that infects the bodies of their victims, and leaves them to hunt others. In these stories, the zombie isn’t only a horror: it’s the last retort of a natural world that this society has long sought to bring under control. The nature that birthed us, now twisting us into something less-than-human.

This is the threat that feels the most vivid now, the last unconquerable weapon of the living world. We brought most species on the planet to heel. We chased many of our animal competitors and great predators into near-extinction. We display the survivors in zoos in tacit testament to our control over them, or just a delight for children.

But the smallest lifeforms on our planet, the ones we cannot see, this is the fear we cannot shake. We have made great strides in medicine, but never won the war we daily fight against microbial life. We live in a time of increasing antibiotic resistance, dense urban environments and vast animal agriculture acting as hotspots for infection.

And above all, we live in a time of travel that can move people and pathogens to the other side of the world within hours, faster than any public health response we devise could catch up to. So it was in these last two months, as headlines breathlessly tried to keep up with the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus.

They beat out everyday, like a parade: the first case reported in Dubai, in the United Kingdom, in Wisconsin. A headline some weeks back asked if coronavirus would come to Canada; by late January, it had, with just a few confirmed cases, none of them critically ill and all of them recovering well.

There is fear in these stories, and in much of the discussion that surrounds them: on social media, misinformation and fearmongering has spread like wildfire. But fear does not lead to good policy or good reporting — and as news now all too painfully shows, panic does not lead to being good neighbours.

One of the least surprising but most heartbreaking effects of the coronavirus outbreak, is how it has inflamed bigotry. Across the country, Chinese-Canadians have reported being targets of xenophobia, similar to what the community in Toronto endured during the 2003 outbreak of the SARS virus.

At a dentist office in Toronto, a sign told patients who had been to China, or knew anyone who had been to China, and showed symptoms of illness to cancel their visit. Parents in one Toronto school district started a petition calling for students who had been to China to be “tracked” and told to stay home from school in isolation.

In Ontario, one news story described how two ethnically Chinese boys were taunted by peers through a playground game to “test them for coronavirus.” In a now-deleted tweet, the University of Berkeley, California listed xenophobia alongside anxiety or depression as a list of “common reactions” to coronavirus concerns.

A CTV journalist was fired after he tweeted a photo of his barber, an Asian man, wearing a mask. “Hopefully ALL I got today was a haircut,” he wrote, along with the hashtag #coronavirus. He later apologized, saying the tweet was “insensitive,” but it was impossible to detach from the spread of xenophobic suspicions.

A Postmedia survey last week found the majority of Canadians were carrying on as normal, but that nearly a fifth of us would move if a person who appeared Chinese sat next to them on the bus due to coronavirus concerns, even if that person showed no signs of illness. Manitobans were among the most likely in Canada to agree.

And in Alberta, Premier Jason Kenney was moved to speak out against the threat of xenophobia with a publicized visit to a Chinese restaurant in Calgary, where he told media “the notion that Canadians of one ethnic background would be more likely to carry a virus that doesn’t exist in Alberta is just misinformation.”

It is misinformation and it is bigotry, naked and simple. It has nothing to do with public health, but if it persists it will do real social damage. To believe that anyone with connections to China should be isolated from public participation is a toxic idea; it certainly won’t help the public better understand how to navigate an epidemic.

To believe that anyone with connections to China should be isolated from public participation is a toxic idea.

If we want to tackle the fear of coronavirus — or whatever pathogen will come next — the answers are already in front of us. We need more investment in health care: a system already groaning to supply beds is not sufficiently equipped for a sudden spike in illness requiring hospitalization, regardless of the reason.

We need more investment in public health education. We need more resources to facilitate access to care and quick diagnosis. And we need to highlight and promote responsible medical journalism — and there is much of it out there — which can deliver information to the public with proper perspective and context.

Right now, we do not need panic. Because the thing is, zombies aren’t real. Despite the horror stories we tell, it has never been nature that can render us inhuman; it has only ever been our own fears. If those now let loose bigotry, if they make us cruel to each other, then all we’ll have done is chosen to make our own nightmares real.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.