Health-scare misinformation spreads like a virus

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 31/01/2020 (2139 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Wash your hands. Don’t touch your face. Think before you tweet.

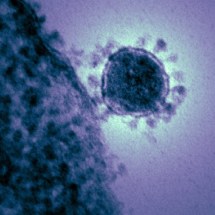

Those three tips may be your best defence against twin viruses: the coronavirus, as well as the viral spread of misinformation about it online.

A new member of the coronavirus family (2019-nCoV) was first identified in Wuhan, China, at the end of December. According to China’s National Health Commission, the death toll in China was at 170 as of Jan. 30. According to the World Health Organization, more than 7,800 people worldwide were infected as of Thursday, the majority of them in China. Canada, so far, has very few confirmed cases.

The virus’s symptoms include runny nose, headache, cough, sore throat and fever, and it can cause pneumonia.

The news of an outbreak of an infectious virus never before seen in humans can be frightening, especially when it comes on blaring emergency-red banners. Dynamic and rapidly evolving situations can make it hard to stay informed, especially with social media acting as an accelerant. Clear communication is a cornerstone of public health — we need to know what to do to keep ourselves safe and what our risks are — but we’re getting a front-row seat to what happens when a virus goes, well, viral.

Over the past couple weeks, the internet has been rife with coronavirus misinformation and wild conspiracy theories — including one involving the National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg. The theory claims that Dr. Xiangguo Qiu and her husband Keding Cheng, the two scientists who were escorted out of the Level-4 lab last summer, are actually a husband-and-wife spy team who were removed from the Winnipeg facility for sending the coronavirus to a Level-4 lab in Wuhan. The Public Health Agency of Canada has dismissed this as baseless.

Canadian public-health officials have not recommended masks or quarantine, and yet, many pharmacies in Canada are sold out of surgical masks. People are reacting out of fear, not fact.

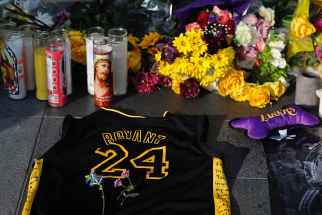

Others are using the anxiety about the virus to justify their own xenophobia. Take the bat-soup panic, for example. Videos said to be showing Chinese people eating bats began circulating online after bats were identified as a possible carrier of the virus. The most popular clip, of a smiling woman eating a cooked bat, is not from China. It’s not even from this year. It’s a 2016 video of influencer and travel-show host Mengyun Wang during a visit to the island republic of Palau, where bat soup is a delicacy.

Under all the many shares of bat-soup photos and videos, there’s a common disheartening comment: “What’s wrong with these people?”

Many Chinese-Canadians are rightly concerned that the racism they experienced during the SARS epidemic in 2003 will rear its ugly head once again. It’s worth remembering, too, that SARS pre-dated social media. It’s so easy — too easy — now for xenophobic sentiments and misinformation to spread online. It’s incumbent on all of us to think critically about the sources of our information.

As for personal hygiene, Canadians would do well to worry more about the flu, which is much more common, can also be deadly and causes thousands of hospitalizations every year. Cover your coughs and sneezes. Stay home if you’re sick.

Wash your hands. Don’t touch your face. And think before you tweet.