Jurors didn’t hear judge defend their right to decide, deny defence bid for him to acquit Raymond Cormier

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/02/2018 (2847 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

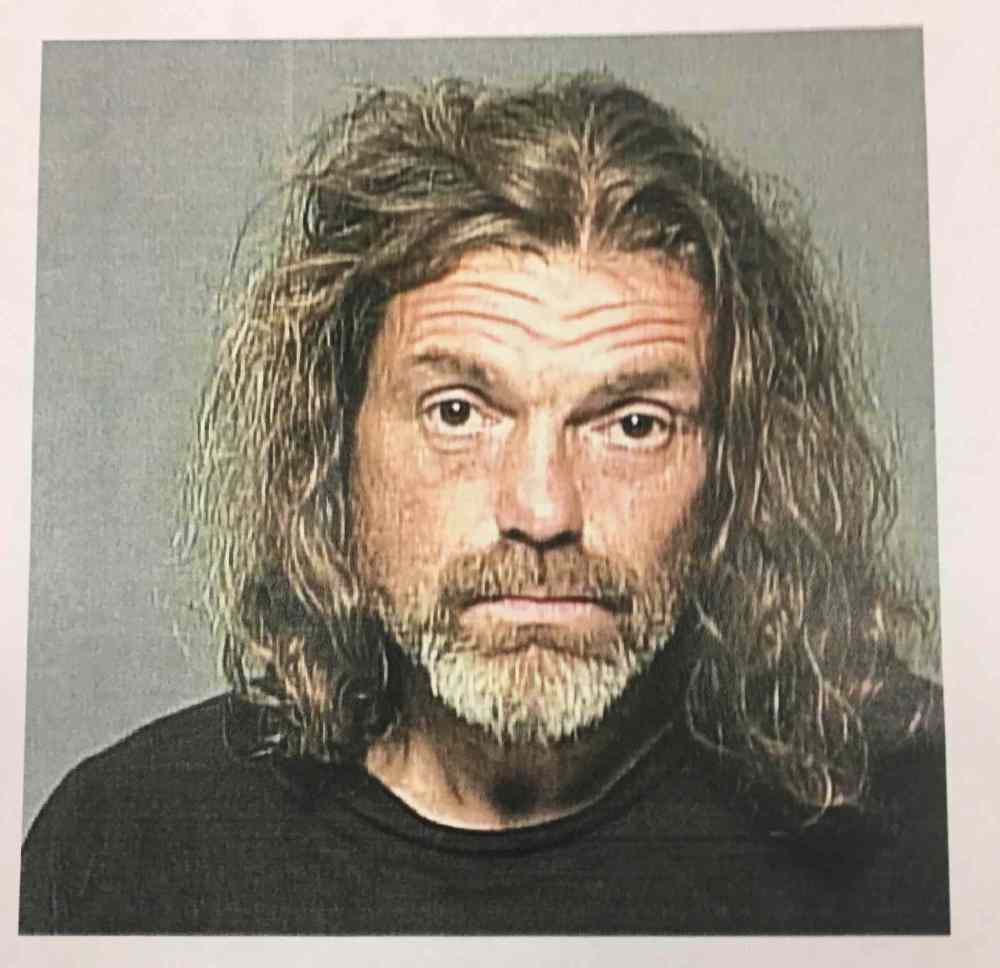

The jury that will decide whether 56-year-old Raymond Cormier is guilty of killing 15-year-old Tina Fontaine has begun deliberations, unaware that the accused killer’s defence lawyers tried to have the case tossed for lack of evidence.

After Crown prosecutors presented all of their evidence against Cormier, who pleaded not guilty to second-degree murder, his defence team argued there wasn’t enough to convict him. They asked Court of Queen’s Bench Chief Justice Glenn Joyal to deliver a “directed verdict,” meaning they wanted him to acquit Cormier without putting jurors through their deliberations.

The argument didn’t fly with the judge, and after he ruled against it, Cormier appeared upset and demanded to speak to his lawyer, all away from jury members’ eyes and ears.

The Crown’s entire case, defence lawyer Andrew Synynshyn argued on the 14th day of the trial last week, was built on speculation. No properly instructed jury would be able to reach a guilty verdict, he suggested, so the case should effectively be dismissed.

“This is where I believe our strongest argument is, is that you have inferences that because a body was found wrapped in a duvet cover that there’s ultimately an unlawful act,” Synynshyn argued in court last week in the absence of the jury. Tina’s cause of death remains unknown, and no DNA evidence was recovered that links her body to Cormier.

“The ultimate question here is, can this jury convict Mr. Cormier at all? Is there a legal basis to do so in fact, is there an evidentiary basis to do so?” Synynshyn said.

“And what we’re submitting is that… (there is) an inference that someone, not necessarily getting into identity at this point, didn’t want, or intended for Ms. Fontaine’s body not to be found. That, I think, is a reasonable inference that can be drawn from the way she was discovered. But we submit that’s where it has to end, because at that point now there is nothing else in terms of how she may have come to be in the river.”

Jurors shouldn’t be asked to speculate on how Tina died, or even whether she died in Winnipeg, Synynshyn suggested, presenting what he described as a “novel” argument to the judge. The defence briefly argued that there was no proof Tina died in this jurisdiction, even though her body was found in the Red River.

“Realistically, it’s the entire case, to some extent, that’s built on inference over inference and speculation. We also would suggest to some extent there’s no evidence of jurisdiction, which is not an admitted element in this case.”

Synynshyn suggested Tina could have been taken out of province between the time she disappeared and when her body was found. Crown prosecutor James Ross called that argument “conjecture and speculation,” that goes against the most probable timeline of events.

Tina was last seen alive Aug. 8, 2014. Her body was found nine days later, on Aug. 17, in the same clothes she’d been wearing the day she was last seen. The pathologist, Dr. Dennis Rhee, who conducted her autopsy, testified Tina’s body could have been in the water for as many as nine days or as few as three.

“It is true that you cannot say on the pathological evidence alone what caused Tina Fontaine’s death. But we don’t just have pathological evidence in this case. We have admissions of an unlawful act from the accused, the concealment of the body, as I submitted to you, and the inference that can be drawn from that,” Ross argued.

Cormier’s admissions, the Crown said, came from secretly recorded conversations collected via probes in his apartment during a six-month undercover Winnipeg Police Service investigation.

“The problem with that, again, is what we have is an interpretation,” of what Cormier’s words meant, Synynshyn argued.

How to interpret the wiretap evidence is exactly what the jury must decide, Joyal ruled. He ultimately decided he would not take that responsibility away from the jurors by ordering an acquittal — “to take that possibility away from them is to usurp the function of the trier of the fact,” he said.

“There’s always a potential to develop the law in areas where it should be developed, but this is an area that’s pretty clear, and it’s clear for a reason. If juries are going to continue to exist, we can’t take away responsibilities that otherwise should go to them,” he said.

katie.may@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @thatkatiemay

Katie May is a general-assignment reporter for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.