Threads of kindness where evil lurks

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/02/2018 (2853 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

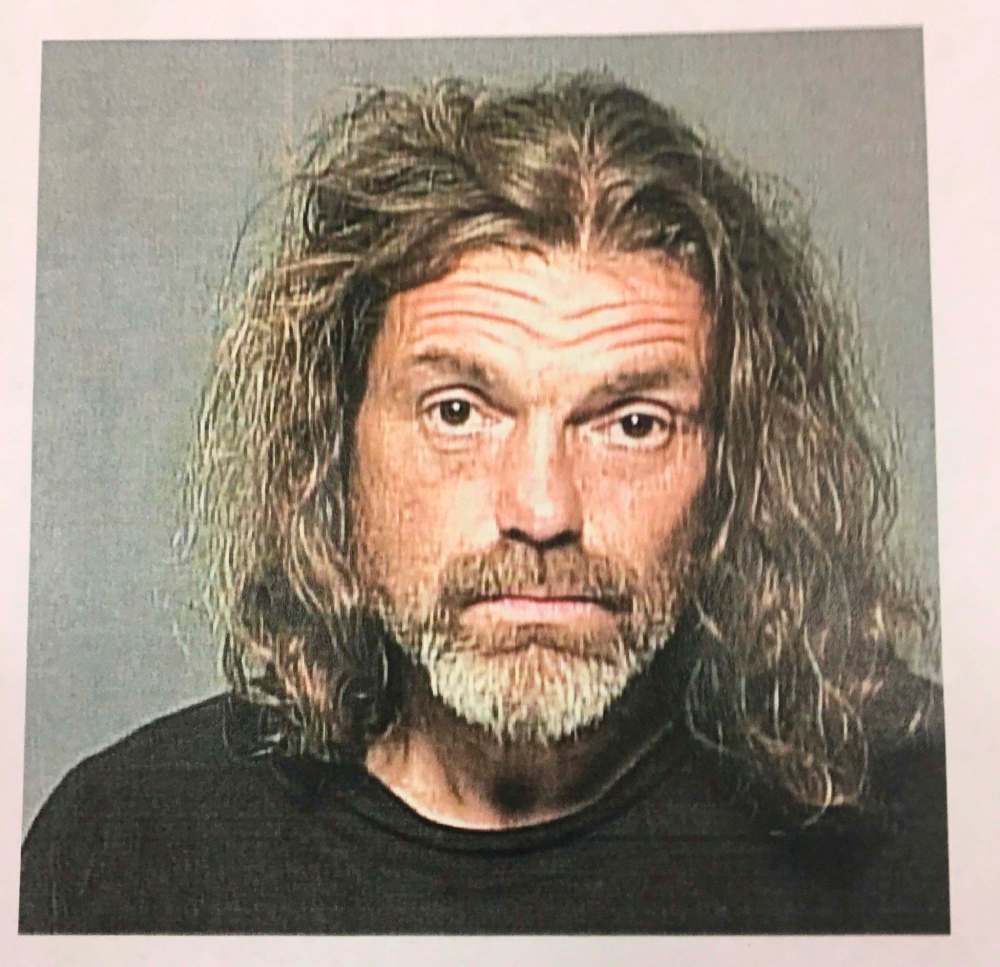

Raymond Cormier did not love Tina Fontaine, or at least, in 2015, that’s what he wanted to tell one of his neighbours.

Only thing was, that neighbour was an undercover police officer. So now, thanks to a hidden microphone the officer was wearing, the jury that will decide whether Cormier is guilty of second-degree murder for Fontaine’s 2014 death, knows it too.

Those tapes fill in more of the story of Tina’s last days. Most of it is dark, but there is a fleck of light in it.

But first, the question of the love that was utterly lacking. In one long 2015 conversation the undercover officer, posing as a neighbour in a Manitoba Housing apartment block, mentioned that Cormier must have loved Tina.

“No,” Cormier replied. “No, no, no, no, no, wrong. I wanted to f— Tina.”

These words, muffled on the tape, thud into the courtroom like lead. Some observers shift uncomfortably in their seats, recoiling, taking in sharp breaths. It takes a moment to rest the hairs standing taut on the back of the neck.

At the time of Tina’s death in August 2014, Cormier was in his early 50s. Tina was just 15 years old, and, according to some who knew her, looked even younger: her hands, one witness told court earlier in this trial, were tiny.

Yet Cormier talked about his lust for Tina on numerous occasions, to that undercover cop and other people in his orbit who listened. To some, he insisted he never sexually exploited the girl; to others, he said that he did, multiple times.

Once, she went to his house: “So automatically I’m thinkin’ ‘alright, I’m gettin’ laid tonight, right?'” he told a friend.

There were other things court heard on Wednesday, that gave a window into how Cormier sees girls and women.

Because there was another occasion, after Tina was dead. This time, the woman was an undercover police officer, posing as a 19-year-old named Jenna. In 2015, she met Cormier in the hall of his Logan Avenue apartment block.

In that scenario, she appeared distressed, banging on a nearby door and screaming for its occupant — another undercover cop — to come out. She was crying, her sobs choking the audio recorded by a hidden microphone.

Cormier emerged from his apartment and tried to console her. He told her to breathe in, breathe out. He asked if she needed to go to the hospital for psychiatric treatment. He urged her to remember there were children in the building.

As he did this, the officer told court, Cormier stood very close to her, right in her personal space.

Yet in October 2015, two months before he was arrested in Vancouver, Cormier seemed content to let “Jenna” die.

On that occasion, the undercover officers staged a domestic violence incident inside their apartment. Cormier later entered to see Jenna appearing battered (thanks to make-up) and comatose (thanks to acting), lying on the floor.

The male officer left it to Cormier to decide how to handle her body, he told court. Few other details about this scene emerged at the trial, but somehow Jenna ended up being carted away in a truck, unconscious and unresponsive.

So whether or not Cormier is guilty of murder — and it is not up to me to decide — evidence suggests he is at least guilty of this, a moral if not legal crime: he saw some of the girls and women who cycled through his life as things.

Things to be used, should it please him. Things to be abused. Things to be f—ed.

And this is the core of the hurt, the root of so much violence against girls and women: the entitlement to take or coerce or exploit bodies which are not or cannot be freely given. This is where so much human unravelling starts.

But there is also this: some people in Cormier’s orbit tried to help Tina, in their own way.

For instance there was Cormier’s acquaintance, Sarah Holland. She did drugs with him and, according to Cormier’s secretly taped conversations that heard in court, once asked what he was doing hanging around with the young girl.

“I’m trying to get laid, what the f— do you think I’m doin’?” he said that he replied.

Holland, according to Cormier’s taped account, told him flatly how young Tina was. (In some versions of his story caught on the recordings, Cormier said he backed off pursuing her at that point; other statements contradict that.)

Holland testified earlier in the trial that on one occasion, Cormier tried to grab at Tina’s breasts. The teen tried to move away from him, eventually taking refuge in Holland’s bedroom because Cormier was “creeping her out.”

Cormier tried to enter the room. Tina and Holland, the latter testified, told him to get lost.

What is awful to think: that could be one of the last flashes of kindness anyone offered Tina, before her body ended up in the river. And she deserved so much more love, care and protection, but maybe that counts for something.

Or maybe not.

– – – –

While the jury in the Cormier trial listened to the tapes, another trial was underway on the second floor of the building. It’s a manslaughter trial against Danny Williams, in the agonizing death of 21-month-old Kierra Williams.

The toddler was rushed to hospital in July 2014, malnourished and suffering from grievous wounds. For this abuse her mother, Vanessa Bushie, was convicted of second-degree murder last year, and sentenced to life in prison.

Yet like Tina, Kierra too had people who tried, with what little power they had, to help her. On Wednesday, court watched video of a police interview with one of Kierra’s older siblings, not yet a teen herself when it happened.

She told an officer about an older sister who had sometimes visited, who never yelled when Kierra cried and instead murmured “shhhhh,” and rocked her to sleep. She spoke about how she would feed her little sister baby food.

“She’d only eat when I fed her,” the girl told police.

There are people who cared about Kierra, and tried in their own ways to help her. People who saw Tina for what she was — a vulnerable child — and at least tried to deter a middle-aged man from turning a lecherous gaze upon her.

In each of their cases, these points of care were not enough to save them.

Yet the fact they exist is something to build on. If there are points of care around vulnerable children, how can we build a society that links them, creates a net, something that will catch and hold young lives safe from the abyss?

It is late afternoon, now. On the street outside the Law Courts building, underneath the arcing steel sculpture that presides over the York Avenue plaza, men with flags march in quiet vigil. One of them holds a sign, calling for justice for Tina.

She is remembered enough to be just Tina, now. Four letters for a life. No last name needed.

And it is Valentine’s Day, and there are no words to say, if not about love. So what do you do? All that you can: you lock eyes with the man holding the sign, put a hand over your heart, and hope that justice, like love, will be done.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.