The perils of civic myopia

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 07/03/2016 (3567 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

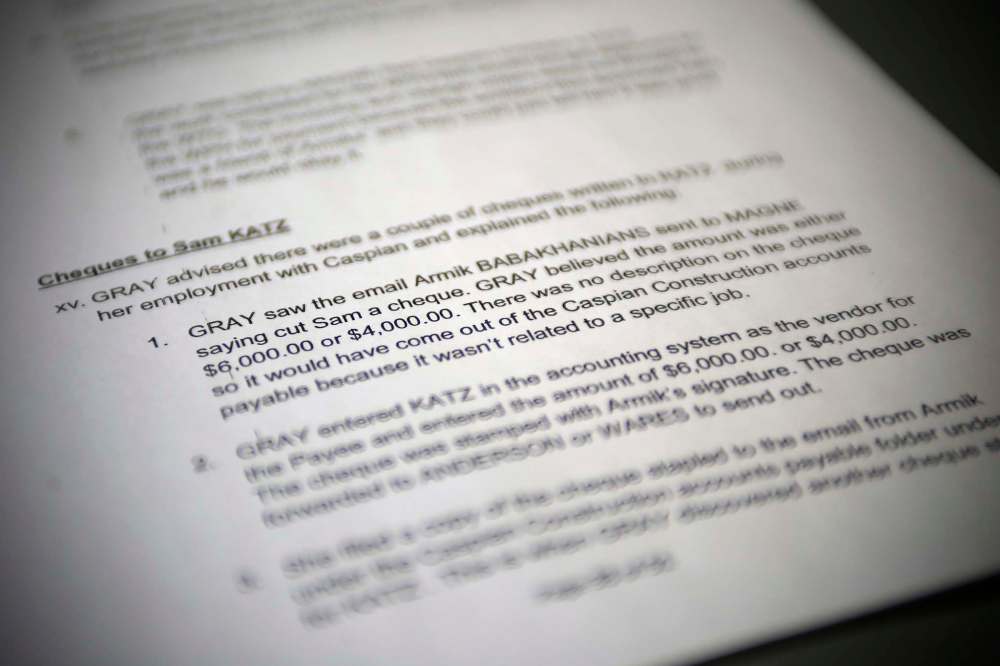

With recent fraud and forgery allegations against Caspian Construction arising from an RCMP investigation, the much beleaguered new police headquarters is once again front-page news in Winnipeg for the wrong reasons. In a recent editorial, the Free Press raised the spectre of the Charbonneau Commission in Quebec as an indication of things to come in Winnipeg. So far, there is little evidence fraud and corruption in this city is on a scale anywhere near what’s emerging in Montreal and Quebec.

That said, elected officials in this city clearly have a problem maintaining oversight of city staff.

Evidence of lack of oversight extends well beyond the police HQ and the city’s decision to spend above a hard budget cap put in place by council. For instance, it was only a few months ago the civic administration’s failure to inform council about structural issues with the city’s new water treatment plant came to light.

Council’s decision last October to allow projects tagged at less than $20 million to go ahead without reporting to the city’s finance committee appears to only exacerbate an issue that has chiefly been attributed to the city’s previous administration under former mayor Sam Katz.

Such decisions are all made in the name of expediency for efficiency’s sake. Unfortunately, both in Winnipeg and elsewhere, there is ample evidence the sidestepping of oversight often leads to much greater costs in the long run.

Every year in my second-year course on city politics, I discuss such examples with my students.

The RIM Park scandal in Waterloo, Ont., is the least salacious of my case studies, but it is particularly apt for comparison to Winnipeg, as the scandal and related boondoggle arose, in large part, from city council’s decision to delegate responsibilities for the financing of a massive multiuse recreation centre to the city’s CAO and CFO. The two men found a private-sector partner to provide “innovative” financing for the $49-million project. Council was told the total cost of the project over 30 years would be $122 million. With part of the cost of repayment to be covered through user fees, councillors were also told the financing would only cost taxpayers $1.2 million a year. The deal came with a caveat, however. When presented to council, councillors were told they had to agree to the deal on the spot or else lose out on savings. Without much debate and few questions directed toward city staff, council unanimously endorsed the deal.

Unfortunately for both city staff and council, they did not adequately scrutinize the document they had signed off on. The city’s private-sector partner, MFP, was not in fact providing the city with some new form of financing. Rather, the city had agreed to hire MFP to find a lender for a regular loan, and to pay MFP a stipend for acting as a middle man. This arrangement only emerged once a journalist for the Waterloo Chronicle decided to write a story on the innovative financing the city was using, alerting the actual lender, Clarica, that something wasn’t right.

It was only as a result of Clarica’s intervention and an eventual meeting among all partners that the true cost of the financing came to light. The city had agreed to pay $227 million after interest over 30 years, almost twice the original estimate. Taxpayers were left paying an additional $3.8 million a year on top of the $1.2 million council agreed on. Not long after this debacle, the city’s CAO and CFO were fired. During the next election, the mayor and all incumbent councillors running for re-election lost. Nevertheless, taxpayers in Waterloo remain on the hook for $5 million a year until about 2030 as a result of this deal and the failure of those tasked with the oversight of city affairs to do their job.

The RIM Park affair resulted in an inquiry, which in turn led to substantial changes in how the City of Waterloo conducts its business. Out of all the recommendations that resulted from the debacle, the most glaring issue was city staff’s failure to present city council with vital information about the deal, and council’s failure to scrutinize city staff’s reports and ask questions.

This same issue seems to plague Winnipeg city hall today. The police HQ may turn out to be Winnipeg’s RIM Park.

Even so, the city needn’t wait to conduct an inquiry into what went wrong in that instance before making changes to how it does business. After all, the city could well blunder into an even bigger boondoggle in the meantime.

Aaron Moore is an assistant professor of political science at the University of Winnipeg specializing in city politics and governance.

History

Updated on Monday, March 7, 2016 6:04 PM CST: Corrects name of commission.