It’s time for a harder look at city hall

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 01/03/2016 (3571 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

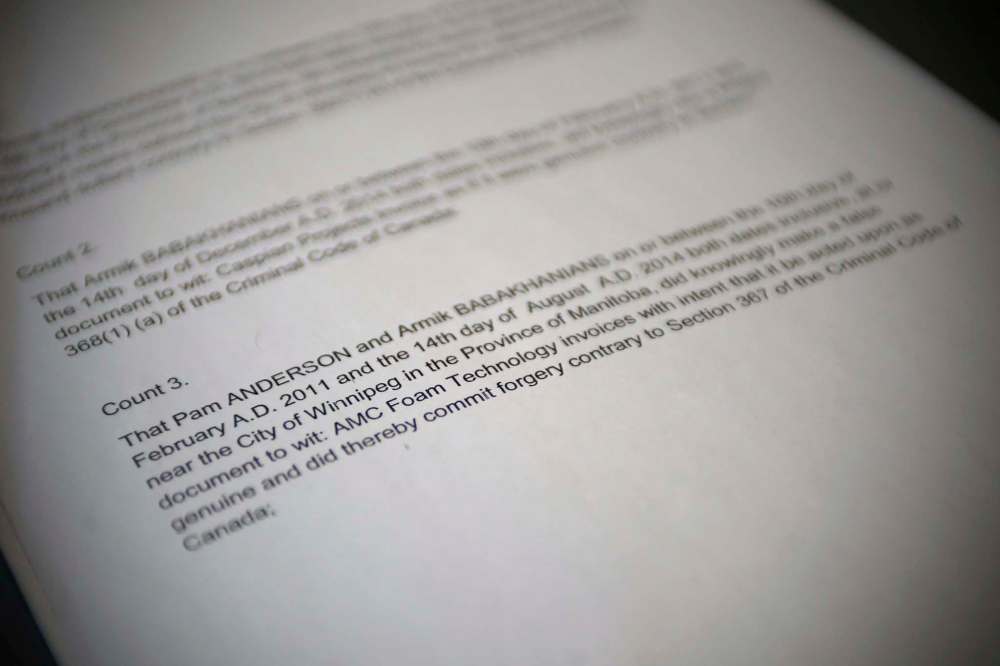

THE allegations in an RCMP search warrant against Caspian Construction are just the beginning of what is likely to become a rising chorus of demands for answers from a cast of characters at city hall and beyond.

Even if the accusations do not lead to criminal charges and conviction, which requires a high standard of proof, there is still enough smoke in the reports of company whistleblowers to expect further action by the province and city.

The absence of criminal charges, in other words, does not necessarily mean the case would be closed.

RCMP have been conducting an exhaustive investigation into Caspian’s billings for the new headquarters of the Winnipeg Police Service, which has cost taxpayers $214 million, roughly $70 million over budget.

RCMP are also looking into the circumstances surrounding the construction of new fire halls and a controversial land swap that seemed to favour a developer over the city. There is no word yet on this investigation.

External audits of these projects did not find any criminal wrongdoing. Auditors did not have the mandate or investigative tools of law enforcement, which shows the limits of independent audits and the need for caution in assessing their results.

The city has conducted numerous audits over the decades, some of which raised ethical questions about the conduct of elected officials, developers and contractors. Some led nowhere, while more recent reviews triggered minor changes to processes.

When the case involving Caspian is closed, the province should consider what it can do to strengthen the way public contracts are awarded and managed.

In Quebec, for example, the Charbonneau Commission was established in 2011 to look into the awarding and management of public contracts in the construction industry following reports of collusion and bid-rigging.

Among other things, the inquiry said the public system was vulnerable to corruption and abuse. A lack of internal expertise and the autonomy of public officials to award contracts were identified as problems. It recommended a special body be established to award and manage contracts.

Three mayors were forced to resign following the inquiry, and two were charged with criminal offences.

Cities are particularly prone to corruption, partly because their processes are less rigorous, but also because individual councillors have considerable power over land development in their wards. Civic officials also have authority to issue large contracts.

Former Winnipeg mayor Sam Katz himself observed in 2007 that private companies had been over-charging the city on major construction projects. “There’s no doubt in my mind,” he said, “the city pays more than the private sector.”

Unfortunately, he did not take any steps to remedy the situation.

Mr. Katz’s entire time as mayor was dogged by the fact he had too many fingers in too many pies. He never grasped the importance of perception and optics, stating on one occasion that he believed “in reality, not perception.”

Well, the reality is he doesn’t look very good in connection with reports he was selling hockey seats and even a portion of an MTS suite to the president of Caspian. Mr. Katz doesn’t see the problem, saying he obtained seats for hockey games, concerts and other events for people all the time.

He also didn’t see any problem using a restaurant he owned to host a party for councillors, billed to the city.

There is no suggestion he benefited personally from the tainted police headquarters project or any other civic project that fell under a cloud during his administration. Other officials, however, may be eventually be drawn into the gathering storm.

The criminal probe might not answer all the questions; they rarely do in these cases. That’s why the province should start considering what it might do to restore trust in the system.

Quebec found a public inquiry was needed to get to the root of the problem. The Manitoba government has that option, too.