Leaf year One year after marijuana legalization, feared increases in use and impaired driving haven't materialized, although the black market remains alive and well

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/10/2019 (2256 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It’s Saturday evening at a Winnipeg weed store.

Shoppers come in quick waves on the way home from work, on their way out for the night or while making their way through a list of errands.

And buying a pre-rolled joint — the smokable symbol of a groundbreaking government effort to replace illegal marijuana trade with a regulated, controlled sector — is an utterly mundane transaction.

To a loitering reporter, nothing seems terribly newsworthy in this little corner of cannabis capitalism. It bears no resemblance to a year ago, when national and international media were on hand to document long lineups of curious shoppers as Canada’s first handful of government-licensed cannabis stores opened for business.

Shopper James Burton embodies the transformation of legal cannabis from hype to predictability in just 12 months.

“It makes life easy,” says Burton, the drummer in a local thrash-metal band, as he waits for a helpful Delta 9 Cannabis employee to transform his just-purchased bud into some joints.

Burton appreciates the sheer convenience of the stores, along with the added benefit of getting it without breaking the law.

“I don’t have to worry about calling somebody at 10 at night. I just know when I can get my weed, and it’s during regular hours.”

Legalization’s debut on Oct. 17 fulfilled a 2015 election campaign pledge from Justin Trudeau, whose Liberal government overhauled the criminal law surrounding the drug and took on the enormous responsibility of regulating non-medical cannabis production. All 13 provincial and territorial governments created their own sales regimes and laws within the federal framework, resulting in 13 different flavours of legalization across Canada.

At this Delta 9 store, there are shoppers who don’t share Burton’s sense of satisfaction. Some still hold a place in their heart for the trappings of prohibition.

“I guarantee you, I could find another guy, and he would be cheaper than this,” customer Paul Bergvall declares.

Bergvall stayed away from marijuana stores at first, having mixed feelings about the way legalization was achieved. The shifting of fortunes from black marketeers to legal corporations reminds him of Pioneers Who Got Scalped, a 2000 album by subversive synth-pop band Devo.

“These (dealers) had it all taken away from them and given to somebody else to look after,” he says.

Bergvall eventually tried some of the shops, but was turned off by the boutique atmosphere and unimpressed with the initial quality of the product on offer. Then again, the weed from his guy wasn’t fantastic, either, and Bergvall noticed the legal stuff getting better over time — so now he’s here, buying government-regulated marijuana, taxes and all.

But he doesn’t believe Ottawa has made good on its promises.

“What I hope is, that they actually do what it said and it drives the prices down. I don’t care if it’s a business or not, to me it wasn’t supposed to be that,” he says. “It was supposed to be something to kill this other market, to save kids, to keep the money out of the bikers’ hands, and all the illegal guys.”

Trudeau’s objectives were lofty, indeed. And after a year of legalization that’s been rolled out unevenly across the country, the work is just getting started.

● ● ●

Eliminating Canada’s deep-rooted illegal weed supply line wasn’t going to happen overnight. Black-market production was worth $4.6 billion in 2017, Statistics Canada estimated before legalization.

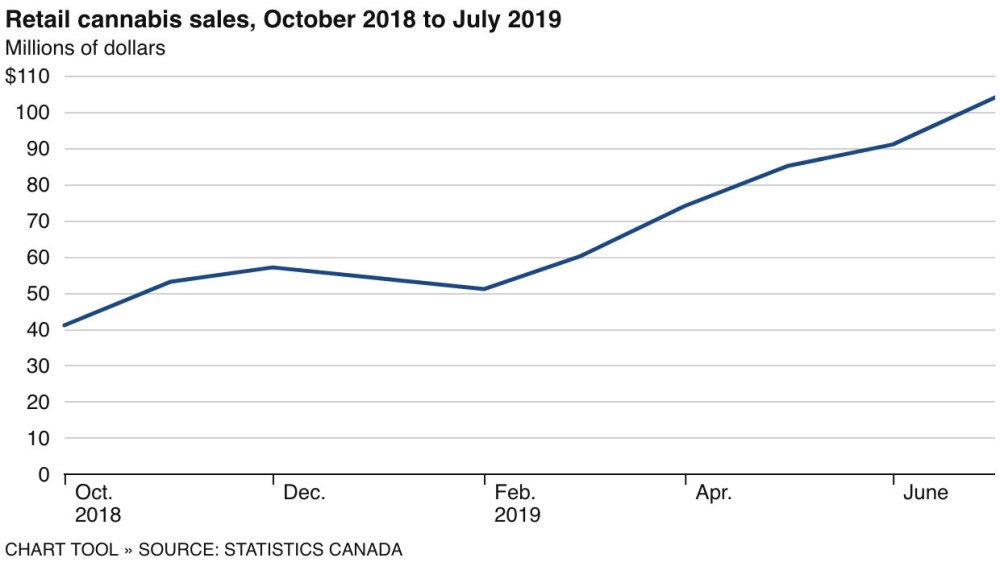

Illegal sales of any product are difficult to measure, of course, but since legalization the agency can track retail activity the same way it watches sales of alcohol, furniture or car parts. The latest data shows monthly cannabis retail sales have grown steadily, from about $41 million last October to more than $104 million in July. It’s an upward trend, despite a temporary dip in legal sales during the first two months of 2019.

“If it were any industry except cannabis we’d be saying it’s fantastic, because we’re talking about sales increases per month that most industries would be happy to get per year,” says Michael Armstrong, an associate business professor at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ont., who analyzes weed market data.

Armstrong suspects Statistics Canada’s $104 million figure in July is actually an under-estimate, citing his own calculations based on data from provincial cannabis agencies.

But no matter how much market share Canada’s marijuana industry has captured so far, there’s plenty more to go; Statistics Canada’s latest quarterly survey of cannabis users found that 48 per cent of current users sourced at least some of their supply from a legal provider during the first half of 2019, and 42 per cent bought at least some from illegal sources. About 29 per cent of current users purchased exclusively from legal sources.

“We’ve got the first chunk of the black market,” Armstrong says.

Friendly Marijua-toba?

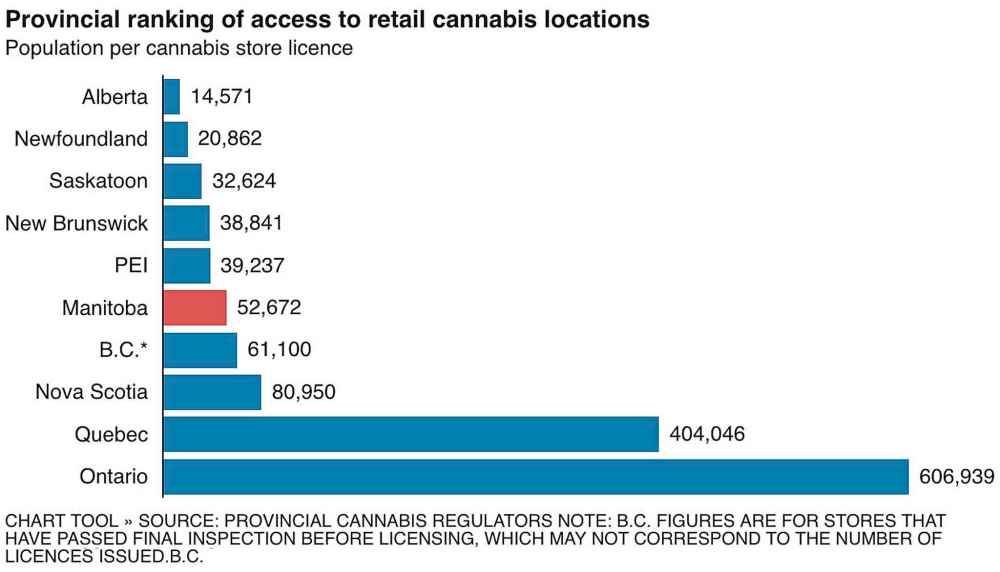

The province has issued 26 cannabis store licences to serve a population of more than 1.3 million Manitobans. That ranks Manitoba sixth out of 10 provinces in terms of population served per licence.

On a per capita basis, Manitobans have better access to retail weed than British Columbians, Quebecers and Ontarians, but worse access than consumers in Alberta, Newfoundland and Saskatchewan.

The province has issued 26 cannabis store licences to serve a population of more than 1.3 million Manitobans. That ranks Manitoba sixth out of 10 provinces in terms of population served per licence.

On a per capita basis, Manitobans have better access to retail weed than British Columbians, Quebecers and Ontarians, but worse access than consumers in Alberta, Newfoundland and Saskatchewan.

The government is working towards issuing licences for more private stores in rural areas, with the ultimate goal of giving 90 per cent of the population access within a 30-minute drive from home.

Manitoba’s licence plate may claim friendliness, but it is less so towards weed users. Even though Premier Brian Pallister’s Progressive Conservative government rejected public cannabis sales similar to alcohol retail at Manitoba Liquor Marts in favour of a private-sector approach, it completely banned home cultivation of any amount and restricted consumption to private property only.

The Tories plan to extend that law to ban the public consumption of edibles, although it’s not clear how the prohibition can be enforced.

It’s also the only province in Canada where the legal age for weed use (19) isn’t the same as it is for alcohol (18).

Statistics Canada estimates that 178,600 Manitobans, or 17.6 per cent of the population aged 15 and older, used cannabis at least once in the second quarter of 2019. That’s a slightly higher rate than the 16.1 per cent national average that quarter, but considerably lower than Nova Scotia (24.4 per cent), New Brunswick (20.7 per cent) and Alberta (20.3 per cent).

Winnipeg-based Delta 9 Cannabis is the only Manitoba company that currently holds the federal licences required to produce and sell the product. Another Winnipeg producer, Bonify, had its licences suspended by Health Canada earlier this year after the company brought in cannabis from an unlicensed source and sold it on the legal market.

In provinces where consumers enjoy the greatest access to retail outlets, such as Alberta and the Maritimes, Armstrong believes legal sales could be capturing more of the market.

Conversely, where things have moved slower — Ontario, British Columbia and Quebec, for example — the battle won’t begin in earnest until retail access improves, he says.

“And then, once we have that, then it becomes more of a head-to-head competition — black market versus legal product. And that’s where pricing becomes more important, that’s where product quality becomes more important and, potentially, advertising as well.”

● ● ●

Hype notwithstanding, legalization doesn’t appear to have had a lasting impact on the overall number of Canadians using the drug. Not yet, anyway.

The first quarter of 2019 saw a bump in the number of people trying marijuana, either for the first time or for the first time in years. But by the second quarter, Statistics Canada estimated that roughly 16 per cent of Canadians aged 15 and older had used the drug at least once in the three months prior — a rate that held steady from pre-legalization, in the same quarter of 2018.

That’s no surprise to University of Guelph associate sociology professor Andrew Hathaway, who has studied how Canadians use cannabis.

“My overall impression is: ‘boy, this is boring,’” he says.

“It’s just an indication that, as has been reported for a long time… the law has never been a particularly effective deterrent. If that had been what was preventing people from smoking weed, we would have seen higher prevalence rates post-legalization.

“So it’s nice that Canada is able to really fully demonstrate that for the first time.”

The widespread, pre-legalization assumption that greater access to legal cannabis would result in higher rates of use simply doesn’t reflect the reality that it has been widely available to Canadians for decades, Hathaway says.

Of course, the long-term effects of legalization on use rates are unknown at this point. But in the meantime, there’s an important short-term exception to the largely consistent demographic of users: older people.

Statistics Canada estimates that among Canadians aged 65 and older, the rate of use increased from about three per cent in the second quarter of 2018 to about five per cent in the second quarter of this year.

“That is a group of more conservative Canadians… and the change in law was enough to bring them over to the dark side,” says Hathaway.

The proportion of baby boomers visiting stores took the industry by surprise in the first few months, says Greg Engel, CEO of New Brunswick-based weed manufacturer Organigram. He calls them “boomerang consumers.”

“There were a lot of people that may have been cannabis consumers 15, 20, 30 years ago and decided, ‘Well, now that it’s legal and I can actually understand what I’m buying and I can talk to people about effects; I’m interested in trying it again,’” he says.

Legalization may have eased the taboo surrounding cannabis for some, but the stigma is a long way from dissipating completely.

“I think the law was one component of the stigma, but there’s a lot more of an informal stigma that tends to be what gets (users) into problems with those who are less approving of it,” Hathaway says.

“It’s still associated with certain stereotypes. You know, lower-class individuals, ‘dirty hippies,’ that kind of stuff and, to a certain degree, I think that’s been maintained.”

● ● ●

Given the presumption that legalization would translate to more users, it’s no surprise that before it happened, much of the discussion was focused on the expectation of an increase in stoned drivers.

It’s difficult to determine whether the worry was justified, since federal crime statistics don’t distinguish cannabis-impaired driving from other drug-impaired driving. Police reports of driving impaired by any drug did increase by 25 per cent between 2017 and 2018 in Canada, to 4,423 offences. But the rate of police-reported drug-impaired driving cases in 2018 (12 per 100,000 Canadians) remained a small fraction of the number of alcohol-impaired driving cases (177 per 100,000).

When the Canadian Press canvassed Canadian police forces six months into legalization, the majority reported no noticeable increase in cannabis-impaired driving charges in their jurisdictions. Anecdotally, some lawyers who work on impaired-driving cases are saying the same thing.

“The majority of my practice is impaired-driving cases, so I see case after case after case,” says Matthew Gould, a lawyer with Winnipeg firm Brodsky Amy & Gould. “And since the legalization, I have had one single case with an allegation of impaired by marijuana, and that charge was dropped.”

Vancouver criminal lawyer Kyla Lee practises exclusively around driving-related offences.

“I have not seen an uptick in any drug-impaired driving cases, and the few drug-impaired driving cases that I have had after legalization, by and large, have not been cannabis-based,” says Lee, adding that the vast majority of her files involve alcohol.

Opiates are most often involved in her drug-impaired cases, she says.

“We would see the occasional charge even before legalization, and I would (still) call it occasional that you see a charge post-legalization…. The short answer is, I haven’t seen anything that I would term a measurable increase in impaired-by-cannabis-related charges since it was legalized,” says Katherin Beyak, a Calgary-based lawyer with the firm Foster Iovinelli Beyak Kothari who focuses mostly on impaired driving.

“I have not seen an uptick in any drug-impaired driving cases, and the few drug-impaired driving cases that I have had after legalization, by and large, have not been cannabis-based.” – Vancouver criminal lawyer, Kyla Lee

Driving impaired by cannabis or other substances was already a crime when the Liberals started their push for weed legalization. Regardless, Ottawa packaged its legislation with another new law that overhauled the way police approach impaired driving. Bill C-46 established new criminal offences for drivers exceeding specific blood-drug concentrations, allowing police to charge drivers for having certain amounts of various drugs in their bloodstream.

Police need reasonable grounds to demand a driver’s blood, so new roadside cannabis saliva-testing devices were rolled out to help officers quickly establish those grounds before conducting blood tests or performing a formal evaluation of whether a driver is impaired.

But Lee, whose firm has obtained and tested the two federally approved roadside saliva testers currently available in Canada, says the gadgets simply don’t perform as advertised. She’s representing a Nova Scotia driver who’s currently challenging the devices in court after testing positive for cannabis at a police checkpoint.

Complicating matters further, the cannabis blood-drug concentrations established by Ottawa have not been scientifically proven to correspond to a certain level of intoxication, unlike blood-alcohol concentrations. Lee suspects government prosecutors have been hesitant to rely on them for that reason.

“Very few charges are being laid in relation to any blood-drug concentration provisions,” she says.

“I think the rationale behind that being that as soon as they go heavy on those charges, they’re going to get people challenging those regulations. They don’t accord with any scientific research, and I think the government knows that they’re vulnerable to a constitutional challenge, and they don’t want to risk having that law struck down before they need to use it in a serious case involving a death or very serious bodily harm.”

“Very few charges are being laid in relation to any blood-drug concentration provisions.” – Vancouver criminal lawyer, Kyla Lee

Gould says he can’t speak to prosecutors’ intentions, but notes that the blood-drug concentration law failed to secure a conviction in the sole cannabis-impaired driving case he’s handled, and it took nine months to resolve.

“What I suspect strongly, is that if people were getting charged (with cannabis-impaired driving), regardless of where it ended up, I would be getting those phone calls, which I’m not,” he says. “So it gives the impression, from my end, that people are not getting charged in the first place.”

The pre-legalization panic around weed-impaired drivers, Gould adds, reminds him of the Y2K computer-bug scare at the turn of the millennium:

“A whole bunch of hype that nothing came of,” he says.

● ● ●

Marijuana advocates and law-reform activists have tried to focus the legalization conversation away from business, and towards achieving justice for people who paid a hefty personal cost for using and selling the drug before last Oct. 17.

Ottawa recently introduced an expedited pardons process for people convicted of possession for personal use only; anyone with a past conviction for growing or selling is out of luck, even if those offences were non-violent and not connected to organized crime.

The special cannabis pardons program waives the regular waiting period and $631 application fee for the pardons, which are formally called “cannabis record suspensions.” Applicants must obtain and provide legal documents such as their criminal records and proof of conviction. If successful, the record of their offence will be set aside, but not permanently erased.

No one knows how many Canadians could be eligible for possession pardons, although Justice Minister David Lametti said his government hopes the figure will “reach into the thousands.”

That means there’s plenty of pardoning left to do: the Parole Board of Canada says it received 129 applications for record suspensions between the program’s Aug. 1 debut and Sept. 30. The board approved 61 of them, 19 were still being screened, 47 were “returned to the applicant as incomplete or ineligible” and two were discontinued for other reasons.

“I mean, it’s good news for those 61 people,” says Toronto attorney Caryma Sa’d, who practises criminal and housing law as it relates to cannabis.

“But I think that number seems small considering the amount of Canadians who have cannabis-related charges. So what that tells me is that not many people actually affected by (cannabis) criminalization have been either able, or willing, to access this regime.”

Meanwhile, Canadians who violate the new federal Cannabis Act could still end up with criminal charges for a variety of new cannabis-related offences, such as possessing more than the 30-gram legal limit in public, knowingly possessing illegal black-market weed or growing more than four plants at home.

Federal criminal penalties for Cannabis Act offences range from tickets for minor versions of some offences, to fines and prison terms. Provincial laws also include some offences that correspond to federal offences, but with lesser provincial penalties.

The Public Prosecution Service of Canada declined to share the number of charges laid so far under the act, saying its internal data is unsuitable for statistical purposes.

But police-reported crime data gathered by the Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics and reported by Statistics Canada shows 1,454 violations of the act in 2018. That’s four per cent of all police-reported cannabis offences in 2018, even though the law was in effect for roughly 20 per cent of the year.

Even before the new law took effect, Statistics Canada says police-reported marijuana offences had been declining for years. The 2018 statistics don’t say whether the violations resulted in criminal charges, or how any charges were resolved.

Illegal imports or exports were the most common Cannabis Act violation in the final months of 2018, comprising nearly 21 per cent of incidents. The next most common weed crime involved adults caught with more than 30 grams of dried flower in public, which made up about 18 per cent of incidents. Another 12 per cent of offences in the period involved youths possessing more than five grams. About ten per cent involved possession for the purpose of selling.

Nearly 1,500 offences in the months following legalization might not jibe with what Canadians imagine when they hear the government “legalized” marijuana. But Trudeau never promised to simply legalize weed and leave it at that; the exact commitment in the 2015 Liberal party platform was, “We will legalize, regulate and restrict access to marijuana.”

However, the platform also said it was too costly to arrest and prosecute cannabis laws that “(trap) too many Canadians in the criminal justice system for minor, non-violent offences.”

But when the act received royal assent and became law in June 2018 the language in the preamble had changed direction from the civil liberties perspective to a focus on public health and the safety of children, Sa’d says.

“More lower-case ‘c’ conservative talking points,” she says.

“I think this is a continuation of prohibition, in some ways. And this isn’t to say that there need to be no regulations or rules whatsoever — but I think that we are repeating some of the same mistakes, in terms of getting people caught up in charges that are effectively victimless crimes.”

● ● ●

From a consumer’s perspective, legalization has more to deliver. Government-regulated versions of cannabis-infused foods could be in stores by mid-December, a few months after new federal regulations take effect Thursday. Potent concentrates called “shatter” and hash, along with topical salves and oil-vaping pens, are part of that second wave of products, which the industry has dubbed Cannabis 2.0.

Organigram’s Engel hopes those new products will help licensed producers capture more market share from the illicit market. He says his company should have vape pens ready to launch in December, but will hold off on releasing some other new products, such as edibles and a powder meant for mixing into beverages, until the first quarter of 2020 in order to ensure a steady supply and avoid the product shortages common after stores opened their doors last fall.

“If you really look about building a brand and building consumer loyalty and looking to have return-purchase consumers, you’ve got to have your product out consistently,” he says.

The pens, which vaporize concentrated cannabis oil similar to the way e-cigarettes vaporize liquid nicotine solutions, are currently implicated in a U.S. public-health crisis in which, as of two days ago, more than two dozen confirmed deaths from lung injuries have been linked to liquid cannabis and nicotine vaping products.

“If you really look about building a brand and building consumer loyalty and looking to have return-purchase consumers, you’ve got to have your product out consistently.” – Greg Engel, Organigram CEO

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has identified 1,080 probable cases of the injuries in 48 states and the U.S. Virgin Islands territory. Only Alaska and New Hampshire have yet to report cases.

On October 4th, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration warned consumers not to use THC vapes.

Engel says he doesn’t expect those health risks from government-regulated vape pens in Canada.

● ● ●

Back at Delta 9, two 19-year-old university students are walking out with a bottle of cannabis oil gel capsules — essentially the same as upcoming legal cannabis edibles, minus the food. The duo were too young to vote in favour of legalization in the 2015 federal election, but now they’re just old enough to buy marijuana in Manitoba. They’re part of the first Canadian generation to grow up with legal cannabis.

Elyce and Meghan don’t want to share their last names, but they’re happy to explain it was never difficult teens to find weed before legalization. In their small group of friends, it’s more popular than alcohol.

“I still live with my parents, and I think (legalization) makes them a little bit more at ease with everything, you know what I mean?” says Meghan.

“My parents were like, completely closed-minded to it before, but now they’re like, ‘OK, maybe,’” adds Elyce.

solomon.israel@theleafnews.com

@sol_israel

History

Updated on Thursday, October 17, 2019 12:38 PM CDT: Statistic fixed.