By a hair Artist specializes in traditional craft of Victorian hairwork

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/10/2019 (2256 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Is there anything worse than finding a hair in your soup?

When it’s not on our head, many people find hair, well, kind of gross, but Winnipeg artist Sandra Klowak finds it inspiring.

“I’m fascinated with human hair because it is a material that is incredibly culturally charged,” she says. “It’s coveted and worshipped when it appears in socially acceptable places, yet it’s reviled when it shows up somewhere undesirable or in unsanctioned forms.”

Klowak, 33, began learning the traditional craft of Victorian hairwork three years ago after being inspired by pieces she had seen at historic houses. With little documentation and supplies that are not easy to find, lessons proved to be a challenge.

“But between a YouTube video of a New Zealand artist teaching a hairwork workshop to kids at a camp and a book I ordered from Utah via the Victorian Hairwork Society, I managed to figure it out.”

As far as sourcing the actual hair, Klowak had to get creative and turned to social media.

“I put a call out on Facebook,” she says. “I’ve received 29 donations of various lengths and I’m still getting them fairly regularly.”

“I need a minimum of five inches (12.5 centimetres),” says Klowak, who is always on the search for more hair, “but the longer it is, the more I can do with it.”

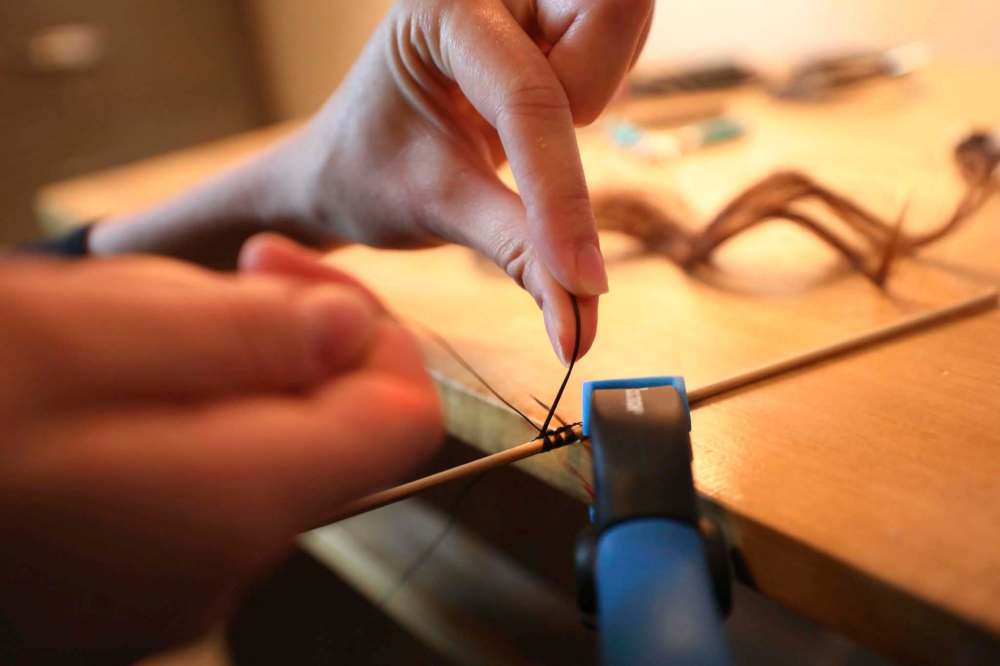

Klowak makes hairwork in the style known as wreathwork or wirework, where the hair is weaved with wire into a series of loops to make designs — typically wreaths or other shapes — that would be framed then hung on a wall.

“I’m inspired by historic hairwork styles, but I don’t limit myself to them. I create framed pieces with flower and foliage themes but my style is generally more minimalist than what you would see historically.”

She also explores different forms such as barrettes, pins and earrings… and doesn’t limit herself to just hair.

“I incorporate other media such as dried flowers and, most recently, discarded cat-claw sheaths, which served as thorns for hairwork roses.”

Klowak’s style of hairwork adds a contemporary twist on a technique that has been around for centuries. Examples can be found in Europe as early as the 16th century, but the craft exploded in popularity during the Victorian era in the 19th century.

“Queen Victoria, the ultimate trendsetter, was a huge fan of hairwork,” she says.

The original intention of hairwork was to memorialize the dead. Later, different styles began to emerge to represent and celebrate the bonds of family, friendship and romance.

While hair may seem an odd choice of medium to represent concepts such as undying love, Klowak notes that hair is extremely durable and long-lasting.

“There are many hairwork pieces going back hundreds of years at least that show no signs of disintegration,” Klowak says. “As far as I know, hair can last thousands of years.”

The longevity of hairwork is hard-earned: it’s an intricate process and it takes a substantial amount of time to create even the smallest pieces.

“One flower can take a few hours, but a larger piece made up of many flowers, tendrils and leaves can take days or weeks to complete,” Klowak says. “You see some historic wreaths that are so full and detailed that it must have taken the artist months to finish — it’s absolutely amazing.”

Amazement is just one of the reactions Klowak’s work evokes. The most common, though, is fear and disgust.

“It’s often very disturbing to people on a visceral level,” she says. “Perhaps it has to do with finding hair in a place they weren’t expecting, which sometimes seems to give them a similar reaction to finding it in their food.”

But the occasionally negative reactions haven’t deterred Klowak in continuing her work and research.

“Hair and hairwork invite us to engage with concepts of gender, power, control/chaos, the body and more,” she says. “It has the power to immortalize our bodies through art.

“It’s important for us to be able to connect in a real way to those from the past and learn lessons from them, especially in a world where we’re seeing history repeat itself all the time, often in frightening ways. For me, seeing the exact colour of an otherwise inaccessible historic person’s hair really drives that connection to the past home.”

If you want a piece of hairwork of your own, the search can be difficult. There are few artists working in the medium. Klowak hasn’t found any peers locally or in Canada, but connects online with a small international community.

She happily does commissions — and all she needs is your hair.

“I work with the customer to come up with a custom design and set a price based on what they want specifically,” she says.

“It could mean creating a memorial piece with hair from a loved who has passed away or creating a unique piece of art in celebration of someone living — such as with hair from a child’s first haircut — or as an intimate, one-of-a-kind gift.”

For those who want to learn how to make their own pieces, Klowak will teach at a workshop on Oct. 20 (1 to 4 p.m.) at the Manitoba Museum. Participants will learn to make a hairwork flower from start to finish. Supplies and synthetic hair will be provided.

“But people are welcome to bring their own hair if they like,” she says.

Klowak’s work can be seen today from 11 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. at the Into the Mystic Metaphysical Expo at the Masonic Memorial Centre at 420 Corydon Ave.

To register for the hairwork workshop, visit manitobamuseum.ca.

frances.koncan@winnipegfreepress.com

Twitter: @franceskoncan

Frances Koncan (she/her) is a writer, theatre director, and failed musician of mixed Anishinaabe and Slovene descent. Originally from Couchiching First Nation, she is now based in Treaty 1 Territory right here in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.