Tender roots, fierce pride Anger, joy, connection 80 years after Japanese-Canadian grandmother was dubbed an enemy alien

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/04/2022 (1334 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

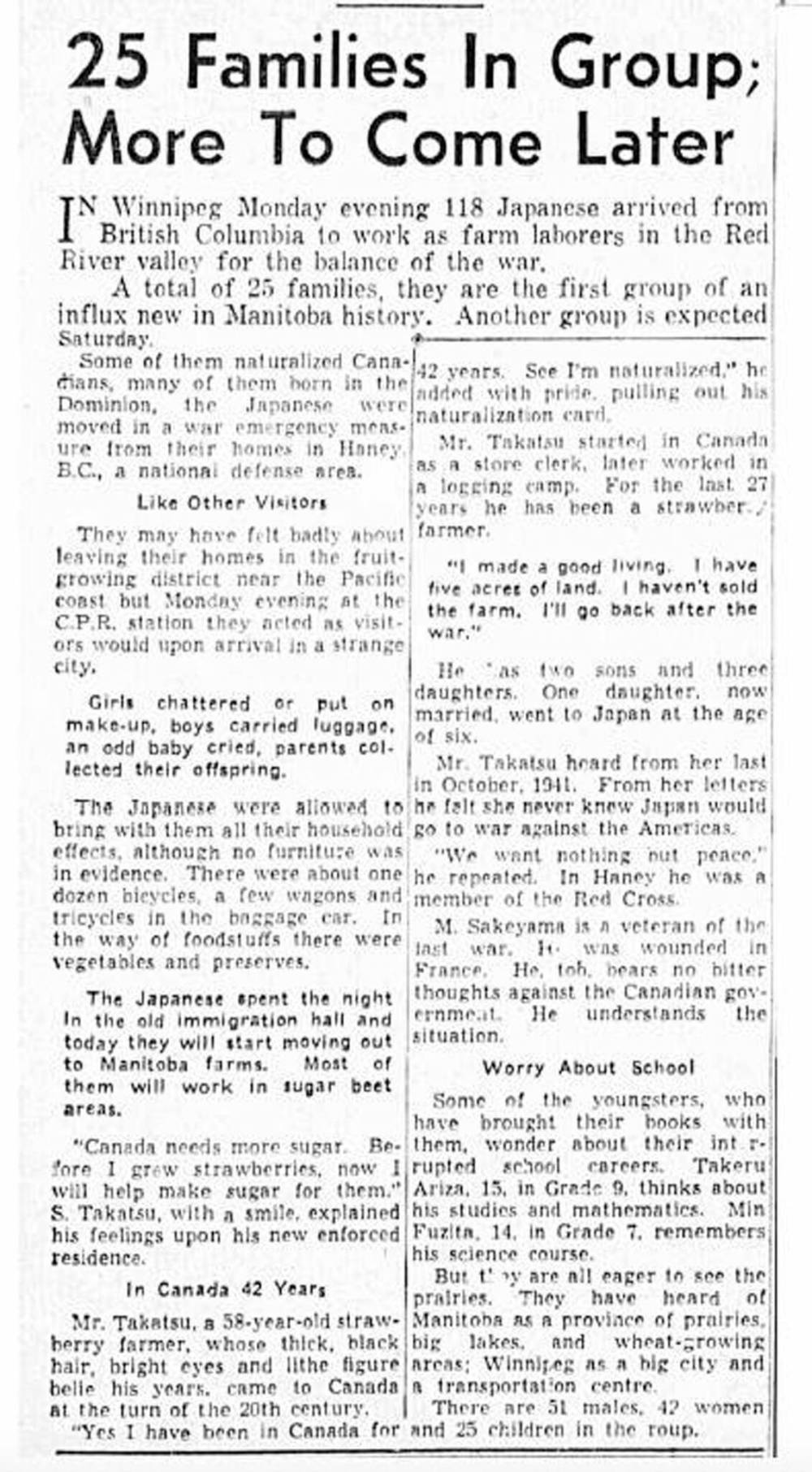

Eighty years ago today, my grandmother, Rosa Takatsu, appeared on the front page of the Winnipeg Free Press. She was just 17 when her family came to Manitoba, among the first Japanese-Canadians to arrive via train after being forcibly displaced from their B.C. homes by the Canadian government under the War Measures Act.

Underneath my grandmother’s photo, a banner headline expressed concern regarding the arrival of these ‘Japs’, in language typical of its day that now reads as archaic at best and racist at worst, describing people who could still be alive, remembering what it was like to be forced from their homes. The Free Press describes an attitude of co-operation among the 118 newcomers, armed with decades of farming experience to serve in their new homes.

Though the headline is 80 years old, the dehumanizing language of the report remains jarring, especially while aimed at the closest connection to my own heritage and generational family trauma.

The federal legislation that forced the ‘Japs’ from their homes and livelihoods came months after the Dec. 7, 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbor. More than 22,000 Japanese Canadians were torn from the lives they knew on the west coast of British Columbia, and were dispersed among internment, labour and road construction camps. Some were forced into farming contracts across the Prairies and Ontario. Many of these so-called enemy aliens were naturalized Canadian citizens, as well as their first-generation offspring.

Dispossessed of their assets in Haney, B.C., the Takatsus opted to farm sugar beets in Manitoba to remain together as a family. Rosa and her loved ones — father Shunsuke, mother Tatsu, brothers Kojiro and Henry, and sister Alena — settled as best they could into their assigned dwellings: a gutted livestock coop in La Rochelle, Man., located at the present-day junction of Highways 23 and 59 just south of St. Pierre Jolys. Like the rest of the displaced population, the family’s assets and possessions were reduced to what could fit in a single suitcase.

“Canada needs more sugar. Before, I grew strawberries, now I will help make sugar for them,” Shunsuke is quoted amicably in the April 1942 Free Press story. As an experienced former strawberry farmer in Haney (now Maple Ridge), Shunsuke’s graciously complacent attitude reflected that of many of the new arrivals, going through the displacement quietly, keeping their heads down and wits about them. “Shikata ga nai” (in English, it cannot be helped) became the emblematic phrase through these years, a symbol of the community’s dignity in the face of remarkable injustice.

“Canada needs more sugar. Before, I grew strawberries, now I will help make sugar for them.” – Shunsuke, April 1942 Free Press story

In the post-war years, the Takatsus settled in Winnipeg. Rosa took on domestic work and manual labour, such as housekeeping and cotton picking, in and around the city before marrying and starting a family in the North End on Boyd Street. Her husband, George, was a sign-painter who seldom spoke of his time in Ontario road camps, if at all.

Fearing a repeat of history, Rosa and George worked hard to protect their seven children from the lingering prejudice against the newly established Japanese Canadian community. The kids, my aunts and uncles, were the Sansei — third-generation Japanese Canadians, the grandchildren of immigrants. They were given western names, spoke no Japanese, and, like many other Sansei in North America, married interracially (fourth-generation Japanese Canadians, or Yonsei, are famously mixed). Commonly referred to as “whitewashing” today, assimilation into “Canadian” culture was pushed out of both love and a paralyzing fear of further racist persecution. Today, Japanese Canadians are among the most assimilated and integrated ethnic groups in the country.

—

After I was born, my parents worked hard to support their new family. Every moment away from them I spent with Rosa in her Transcona home, where my aunts and uncles primarily grew up. She helped to raise me, the youngest of her four grandchildren.

As a librarian in her later life, she showed me the bright yellow shorts dutifully painted on the illustrations of Max’s naked body in every copy of Where the Wild Things Are after a parent complained. She fed me cold tofu with shoyu, inari (“rice bags”), and child-sized cucumber maki. We folded origami, tended to her prolific garden, visited her library, watched Studio Ghibli animated films, and counted to five together in Japanese. I was eight years old when she died, and my frail connection to my Japanese roots seemingly went with her.

As time went on, no social studies nor history class covered this dark period affecting my family. For me, the extent of the plight of the Japanese Canadians was obscured until university, when I was assigned a paper on a 20th-century historical event of choice. Diving deep through government archives and comprehensive publications, I learned of the cruel bigotry inflicted upon those who raised me, and ultimately resolved to explore the family history and connect with the local community.

As time went on, no social studies nor history class covered this dark period affecting my family. For me, the extent of the plight of the Japanese Canadians was obscured until university, when I was assigned a paper on a 20th-century historical event of choice.

By consuming every and any resource available, I was able to slowly piece together the Takatsu family’s journey through dispossession. After many hours spent in the Japanese Canadian Association of Manitoba’s condensed library tracing registration cards and land titles, census records and immigration papers, reclaiming the lost aspects of my heritage felt like a radical act of resistance, something not afforded to many of the older generations.

Today, communities of Japanese Canadians exist and gather in cities across Canada. Many of these community members share journeys eerily similar to my grandmother’s, and all are undoubtedly touched by the events of the Second World War in one way or another. But still, healing continues — arts and cultural festivals celebrate the heritage and history of the Nikkei, or descendants of Japanese immigrants, inviting us younger descendants to rediscover our roots and reclaim what our grandparents lost.

Sydney Christie is a Winnipeg freelance writer.

.jpg?h=215)