WSO conductor helped wife, mother-in-law flee Ukraine Russian-born maestro suspends all future work in his home country

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/03/2022 (1085 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine hit shockingly close to home for Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra music director Daniel Raiskin.

His wife, Larissa, and his mother-in-law, Galyna Reznikova, barely escaped war-torn Ukraine with little more than the clothes on their backs after a perilous, 40-hour train ride to the relative safety of Slovakia late last month.

“Total disbelief,” Raiskin says of his state of mind over the phone from Bratislava, Slovakia’s capital. The Russian-born maestro has led the Slovak Philharmonic Orchestra as its principal conductor since 2020 and had been preparing for a concert when the first missiles began raining down on his Ukrainian wife’s birthplace of Kharkiv.

“This has been a terrible example of how close this tragedy can get to your own front door, and how it can dramatically impact your loved ones where you feel completely desperate. This is not a movie,” he said in an interview Saturday.

Raiskin recounted how his wife made the decision to take one of the last planes flying into Ukraine from Europe in late February. She travelled via Istanbul from their Amsterdam home to the country’s second most populous city of 1.4 million to support her mother, alone and waging her own battle with cancer, having just begun a gruelling new round of chemotherapy that week.

As the Russian bombs and missiles grew more deafening, and after Larissa texted her husband at 5 a.m. on Feb. 24 saying they were under rocket attack, the family made the gut-wrenching decision for the two women to leave Kharkiv, joining the now 2.7 million — and counting — Ukrainian evacuees desperately attempting to escape their ravaged homeland.

After waiting 45 minutes in sub-zero weather on the street, a kindly passerby finally offered to drive them to the local train station, where they were joined by hundreds of fleeing passengers.

Squished into a railcar originally designed for four passengers with 11 others, including a five-year old child and a cat, they began slowly snaking their way through western Ukraine for what is normally a 16-hour journey, first stopping at Kyiv, by then nearly surrounded by Russian forces. They were accompanied by a barrage of shelling and the wails of air-raid sirens, often travelling in complete, terrifying darkness to avoid detection by the Russian military.

Feeling helpless in Bratislava, Raiskin kept in “sketchy” contact with his family members throughout the ordeal. Fearing losing precious battery power on her cellphone, Larissa could only send short messages and text one-word names of train stations they had just passed to let her husband they were still alive, safe, and on their way.

They eventually made it to Ukraine-Slovak border, where Raiskin had been anxiously waiting, literally parking his car by a potato field.

“There were many tears and we were able to kiss and embrace each other, but still had to walk a few miles to my car, which was parked outside the village,” he says, noting the border had been closed by the military to avoid potential influxes of journalists and gawking, curious bystanders.

“We were getting warm pizza shoved into our hands, with volunteers from both sides of the border asking us if we had transportation and somewhere to go. Happily we did,” he says. The trio left for a hotel an hour’s drive away to rest overnight before the next leg of their journey to Amsterdam.

“There were many tears and we were able to kiss and embrace each other, but still had to walk a few miles to my car, which was parked outside the village.” – Daniel Raiskin

However, Larissa’s mother unexpectedly tested positive for COVID-19, becoming too ill to travel further.

She is now fighting for her life with COVID-19-related pneumonia in a Bratislava hospital, with the Raiskins “hoping and praying” for her recovery. However, they are deeply grateful to be together, with the conductor acknowledging that his wife and mother-in-law were still the “lucky ones” to get out with millions unable to flee.

The couple will remain by her side; their son Ilia, 23, and daughter Sophia, 18 are both living in Amsterdam and they hope to take turns visiting them as soon as possible.

The conductor, who has been on the WSO podium since 2018, had been billed to lead this past weekend’s (A)bsolute Classics concert, featuring Ukrainian-born Israeli violinist Vadim Gluzman performing Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto, Op. 35. Associate conductor Julian Pellicano filled in during his absence.

Saturday night’s program, whch opened with the Ukrainian National Anthem, Shche ne vmerla Ukraina, included Raiskin’s pretaped video greetings from Bratislava, where he introduced his last-minute program change to include Hymn 2001 by 84-year-old Kyiv-born composer Valentin Silvestrov, who had escaped to Berlin three days prior from Ukraine. His stirring string orchestra work offered a message of peace and solace for the 21st century.

Raiskin was audibly exhausted from stress and worry during the interview, but his voice flashed with anger when speaking of President Vladimir Putin, the “monster” leading Russia. Raiskin, who left what was then the Soviet Union in 1989 at age 20, has openly condemned the Russian government for its “senseless barbarism” and atrocities being inflicted on a peaceful sovereign nation.

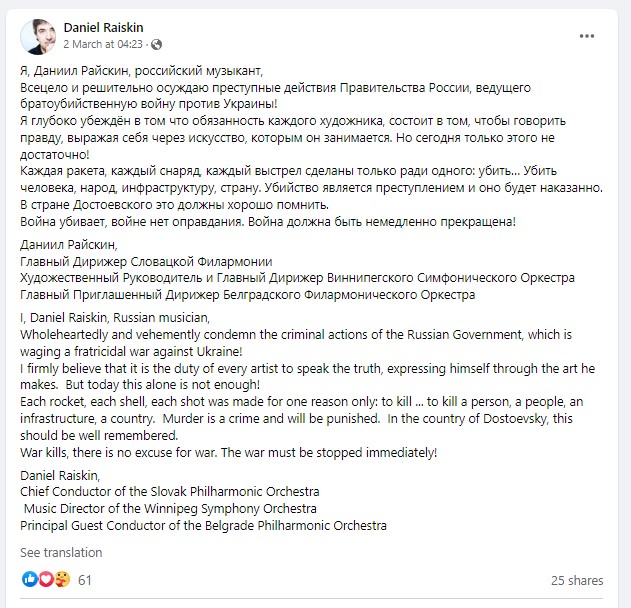

Having made regular past guest appearances with the St. Petersburg-based Mariinsky Orchestra, Moscow Philharmonic, and the St. Petersburg Philharmonic Symphony, among others, the conductor posted a strongly worded statement on his personal website, the WSO home page and his own Facebook page in which he formally suspended all future work and concert engagements in Russia. He says this will last for the foreseeable future, or at least until there has been a radical change in the Russian regime, underscoring that his career-altering decision has been made not for political reasons, but out of respect for “universal basic human values, rights and responsibilities.”

“The probability of me seeing my 86- and 85-year-old parents soon is zero, and still alive is questionable.” – Daniel Raiskin

Raiskin, the son of a prominent Russian musicologist and mathematician, grows resigned when asked when — or if — he expects to see his elderly parents again. They still reside in his native city of St. Petersburg, where Raiskin attended the famed conservatory that claims such illustrious alumni as Tchaikovsky, Prokofiev and Shostakovich.

“The probability of me seeing my 86- and 85-year-old parents soon is zero, and still alive is questionable,” he says frankly, adding that he keeps in touch via telephone. “This is one of the things that is giving me lots of torment and pain, but I can’t stay silent. I feel that especially for us artists, our primary duty is to speak the truth whenever we can, and if it’s possible, to express it through the art we make. You have to stand up and be loud and clear about what you believe in.

“But I can tell you that my parents have seen a great deal over their lifetimes; as children, the horrors of the Second World War; later, the repressions of the Soviet state. They remember everything very well, and are under no illusion of what is happening today.”

holly.harris@shaw.ca