In timely fashion Electrician deserves a big hand for keeping clock at city hall up to the minute

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/03/2022 (1459 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

At 7:40 a.m., on the second Monday in March, Mike Pereira punched the clock at city hall.

At 8 a.m., he changed it.

The city electrician went up the elevator from the main floor of the Susan A. Thompson Building — the city’s administrative building — wearing a white hard hat. He opened a door on the seventh floor before climbing up a sunny flight to the eighth tier. There, he put on his gloves, shimmied up a ladder, and pushed open the hatch to the rooftop, where he belatedly took the City of Winnipeg out of the past and into the present.

The two-sided clock on the roof was an hour behind, because the day before, daylight time (often called daylight saving time) officially began. The task of saving the daylight this year fell to Pereira.

If the 57-year-old electrician had his way, he’d have been been up there the day before. “I would not mind going in on Sunday,” he says. “But that would mean overtime.”

So he’s a day late and an hour early. When he got to work Monday, the clocks read six when they should have read seven, and to someone who respects precision as much as Pereira, that was an issue that needed to be fixed as quickly as possible.

“I’m a very punctual person,” he says, wearing his work watch, a military-green Timex Combat Commander, which he says is one of the thinnest and lightest watches on the market. “If that clock is not set and Mayor (Bowman) sees it, we will hear about it.”

To set the clock, Pereira sidles carefully across the icy roof, where he opens up a metal panel on the clock’s south-facing side. Inside is a control panel, on which is a switch Pereira flips to speed up the arms of the 3.6-metre-wide, 3.6-metre-tall, 25-cm-deep timepiece. It takes about 10 minutes for the arms to revolve one hour, depending on the wind and the temperature. In the winter, the arms tend to take their time to go around the face.

As a City of Winnipeg electrician, Pereira gets the chance to tinker with the wires in any of 1,600 buildings on a given day. But working with the clock is a special privilege that comes with a vantage few are ever afforded. From the top of the Thompson Building, he is at eye level with the cornices of the Exchange District’s oldest buildings. He can spot the ornate domes of the historic North End churches. He can see the way Main Street curves in a way nobody on the ground ever could.

“It’s nice to work outside,” he says. “Out here, you’re alone. No one bothers you. And the views are just fantastic.”

He also gets up close to the clock, which has quietly ticked above King Street since 1974. He can see the patina: the yellowing panels, a football-sized smudge on the south face from an oil leak. He can even look inside, where he sometimes has to rid the mechanism of dead gnats and dragonflies. Every timepiece needs maintenance and a watchful eye.

This clock came late. When the city built its new civic complex to replace the “Gingerbread” City Hall — a grand Victorian structure built in 1896 — there was no timepiece included. The former city hall had a four-sided clock, which hastened the end of the Gingerbread era.

“At the end of May 1961, Council Chambers on the second floor of City Hall were closed as a result of an architect’s assessment that the clock tower was structurally unsound,” a city report says. “It was, in effect, the final straw.”

Work on the new civic centre began in 1962, and it officially opened in October 1964. Ten years later, as Winnipeg celebrated its 100th anniversary, the city got its clock back, and it didn’t pay a cent.

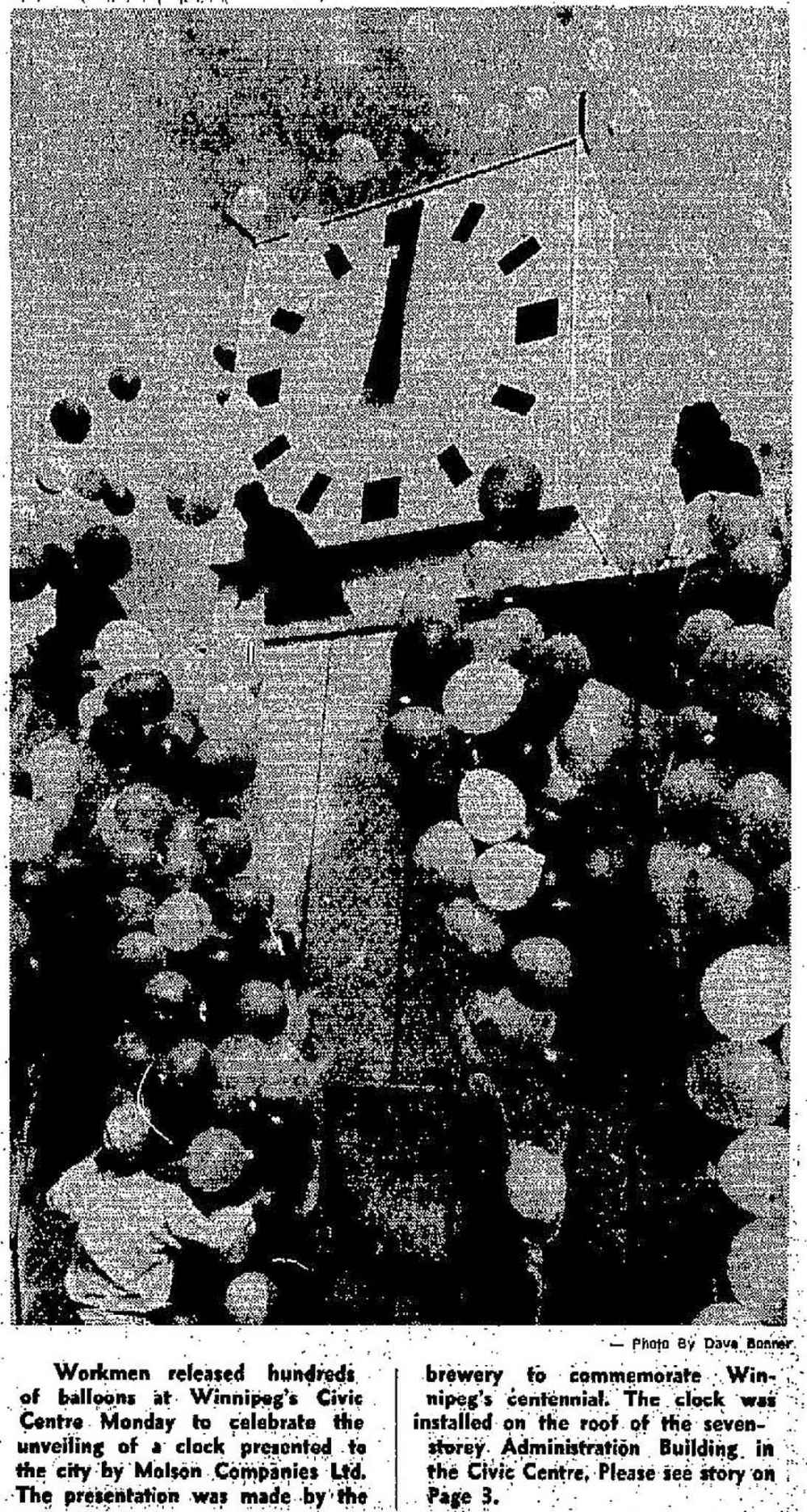

It was a gift from D.G. (Bud) Willmot, the chairman of the Molson Company Limited, a brewing corporation with a local workforce topping 800. Molson commissioned Winnipeg’s Claude Neon Company — which also painted the portrait of Queen Elizabeth at the old Winnipeg Arena — to fabricate it, and when it was unveiled on Sept. 16, 1974, Molson made sure the clock’s first moments were a spectacle, replete with balloons, scotch and likely a keg or two.

Willmot gave prepared remarks from the adjoining balcony over the city’s sound system, followed by comments from mayor Stephen Juba, who unveiled the clock to a crowd on the complex grounds. Then, 600 helium balloons were released into the sky, 200 of which contained a printed card promising those who retrieved it a single silver Molson centennial dollar if brought back to city hall.

Juba and his council then invited the Molson brass to lunch at the private dining room at the William Tell restaurant, followed by cocktails and a reception aboard the River Rouge cruise ship.

On that day in 1974, Mike Pereira’s older brother, Emmanuel, was one of the lucky 200 to catch a balloon, and promptly went downtown to retrieve his dollar. “Here it is,” the electrician says, holding the coin — embossed with the profiles of Winnipeg’s first mayor, Francis Evans Cornish, and its longest-serving, Juba — in his palm nearly 50 years later.

After people found out it was often his job to set the clock, Pereira started getting calls from friends to tell him it was off. “I call central control and ask them to walk outside and check both sides,” he says. “It’s not a bad joke.”

“One time, the north clock really was off,” he says. “The roofers plugged into the circuit, tripped it, and didn’t say anything. Nobody noticed until a friend called me. He says he was coming up the Disraeli and noticed it was three-and-a-half hours off.

“I went out and corrected it,” he says. “Sure enough, someone called and said thank you.”

Though clock duties are divided among the city’s electricians, Pereira would be a natural choice to be Winnipeg’s timekeeper. He has a collection of 18 watches, including his father’s Omega Classic, which his dad brought with him when he immigrated from Portugal.

He tinkers with his watches constantly. “If you don’t mind the pun, I like to know what makes things tick,” he says. “Some people want to be doctors or lawyers. Others just want to work with their hands.”

In Pereira’s case, his hands are frequently working on the hands of clocks. Aside from his wristpieces, he has many clocks at his house, and unlike at city hall, he could not stand to wait to adjust them Sunday. However, he is never happy about daylight time’s arrival.

“I think we should scrap it,” he says. “Setting the clocks is kind of ridiculous.” He adds, “I always see a lot of people confused by it. At my house, I have 14 clocks, so I go around from wall to wall, clock to clock. It’s just a hassle resetting timepieces.”

But even if he opposes the concept of daylight time, Pereira is punctual, so he resets his clocks as soon as he wakes up on the second Sunday in March every year. He would hate to be the reason anybody is late.

That’s partly why he cares so much about keeping the clock at city hall as accurate as possible: it bugs him to see its arms telling a different time than the ones on his wrist. For Pereira, that goes beyond punctuality and reaches the point of civic duty.

“It shows people the city is still working,” he says. “If the clock is always wrong, everyone will ask who is maintaining this city. And what does that say about us?”

Ben.waldman@winnipegfreepress.com

Ben Waldman is a National Newspaper Award-nominated reporter on the Arts & Life desk at the Free Press. Born and raised in Winnipeg, Ben completed three internships with the Free Press while earning his degree at Ryerson University’s (now Toronto Metropolitan University’s) School of Journalism before joining the newsroom full-time in 2019. Read more about Ben.

Every piece of reporting Ben produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.