Outside the box Architect of WAG's Inuit Art Centre inspired by the endless space and distant horizons of the North

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 22/10/2019 (2247 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

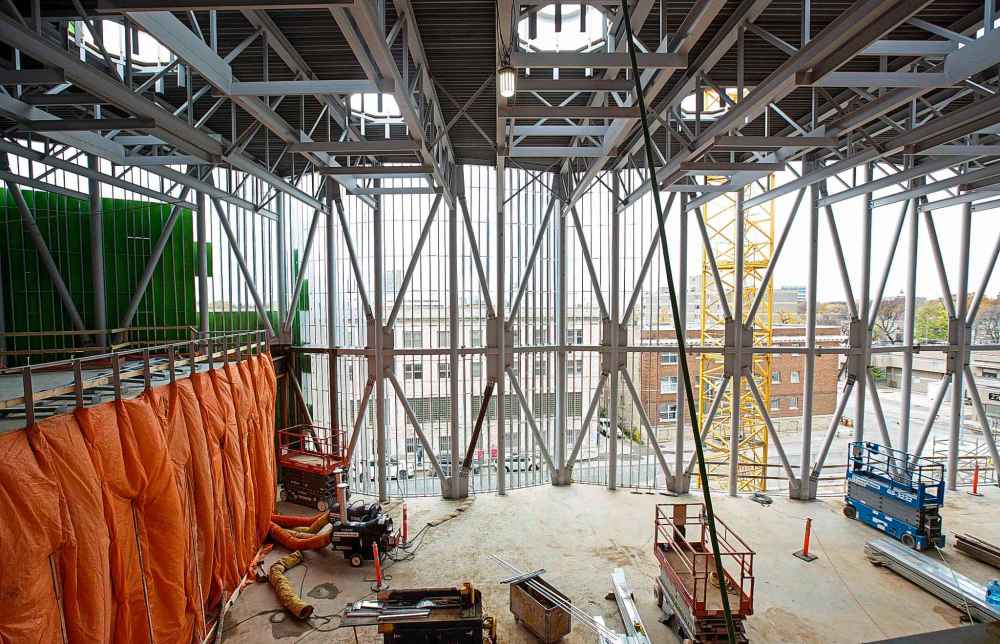

At the edge of the observation deck, Michael Maltzan pauses, his bright yellow safety vest glaring bright amid the lines of soaring steel bars and flat concrete floors. He looks down over the gallery below, or what will soon become the gallery, for now exhibiting only a tangle of cables and crates waiting to be opened.

It is Saturday afternoon at the site of the Winnipeg Art Gallery’s new Inuit Art Centre, the gleaming new facility rising at the corner of Memorial Boulevard and St. Mary Avenue. The construction that buzzes most days is quiet for the time being, so as to allow three tours of the site for a small group of WAG donors and journalists.

The tour rose from the entry atrium, dominated by the serpentine steel frame of the three-storey visible vault, where the gallery’s archived collection of Inuit art will be visible to all who enter. It’s a rare feature for an art gallery: usually, works not on display are locked away in the back of house.

But here, Maltzan explains, all of these things will be in conversation. The artwork, the curation, the second-floor learning centre and the vast main exhibition hall: all of it is intended to flow together, inviting visitors to stream into and through and around it.

He gestures 30 feet over his head, to the curving ovals of 22 recessed skylights that will bathe the gallery in what he calls “diffused and suffused light.” They will give light back to the city, too: at night, Maltzan says, they will glow like a “lantern for the neighbourhood.”

“It has a huge scale, as you can see,” he says.

It is the first time media has gotten a peek inside the new $65-million centre. When it opens next fall, it will house the world’s largest collection of Inuit art in 40,000 square feet of space spanning four levels.

This preview arrives at a pivotal moment in the facility’s construction. Not long ago, the site gave little more than an idea of its final form, sketched in slabs of concrete and naked steel bones; not long from now, it will be clad in a skin of glass and off-white stone, finished to a shine, ready to be filled with art.

So the time felt right, WAG executive director Stephen Borys says, to give the public a sense of how far it’s come. The facility has a shape now, and a presence, and yet it is still open to the October bluster. (Construction crews are focused on closing it in before more winter snows come.)

“It was a chance to see the building both as a frame and an enclosure, and when you’re standing inside you can still look out,” Borys says. “It was a key moment, where there’s this interesting alignment with the design.”

Inuit Heart

In 2016 reporter Randy Turner and photographer John Woods collaborated on a two-part series investigating the impact the Winnipeg Art Gallery’s Inuit Art Centre.

● Northern Stars: Inuit carvings, jewelry and wall-hangings are not just pieces of art; they’re stories – some thousands of years old – spoken by hands

● Raising their voices: The WAG’s Inuit Art Centre will be about people, not just things they create

It’s been about a decade since the WAG started working full-steam on the centre, and more than seven years since Maltzan, in partnership with local firm Cibinel Architecture, was chosen for the design, beating five other finalists from an original pool of 65 applications.

What began then was a conversation about Winnipeg, about Inuit art, and about the purpose of what they were to create. It would culminate in a trip to the North that changed how Maltzan saw the project forever — a project he hopes will redefine the Memorial Boulevard streetscape and draw the communities it serves closer.

It was an interesting challenge. Maltzan had long known the Winnipeg Art Gallery structure; years ago, he says, he’d seen photographs and drawings of the 1971 Gustavo de Rosa structure, considered one of the finest late-modernist designs in North America, and he had a sense of the cultural shadow it cast.

“I was always fascinated by the building,” Maltzan says. “When it was built, it was an extremely adventurous and really avant-garde building, but done with such a sense of how the urban grid was shifting, how the neighbourhood was evolving. It really presents multiple faces to each of the parts of this district of the city.”

The difficulty for his team, he continues, is that the building did not invite an addition. Leaning over a model of the site, he points out its features: the sculptural Tyndall stone prow, looming across the western edge of Winnipeg’s downtown, the bold lines cutting a statement out of the streetscape beyond.

The Inuit Art Centre’s design had to complement de Rosa’s achievement, but it also had to speak of its own vision; finding a balance would be tricky, especially on an odd footprint bounded by loading docks on the WAG’s south end.

“There aren’t that many great pieces of architecture in the world, and this was one of them,” he says. “I didn’t want to mess it up.”

Easier said than done. Art, the team knew, looks best in space that echoes the places it was first made: think 18th-century paintings, Maltzan says, viewed in richly decorated classical-style rooms.

So the Inuit Art Centre, they knew, must not only continue the story started by de Rosa’s building, but also hum with the resonance of where most of its collection was created. Yet the Arctic is not an easy environment for an architect to capture; nature creates on a scale beyond what humans can do.

In the North, Maltzan found his answer. Together with a small group that included Borys, George Cibinel, Maltzan’s family and a photographer, he spent a week travelling Nunavut, hopping from Iqaluit to the hamlets of Pangnirtung and Cape Dorset.

He watched Inuit sculptors at work, carving soapstone. He soaked in the way the summer light filled up the vastness of land, changing hue and tone as the days rose and fell. He marvelled at the scale of it all: the undulating lines of the great ice shelves that loomed over the water, the skies that met the land where both had no end.

When Maltzan landed back in Los Angeles, he was “invigorated,” he says, but nervous too. He had grown up mostly along the East Coast of the United States, and he had always been at home in nature; but he’d never seen anything quite like the sheer scale and ancient energy of the North.

“I really felt like all my preconceptions needed to be thrown out the window,” he says.

In the end, what he took from the North was a story about vastness, and now, he can point out how it speaks through the rising construction. When a visitor comes in, they are greeted by the visible vault, and then by a path of stairs and mezzanine that wraps around and rises to the floors above, flowing from one place to another.

The idea, Maltzan explains, is that the facility should feel open. It may suggest directions visitors can take to explore what it contains, but it makes no firm prescriptions. There is a weight to the building, but an openness, too: the scale of it looms but does not limit, just like the northern horizons.

“There is a fluidity to that landscape which isn’t just about the water,” he says. “It was this idea that their world is not confined by the normal rectangles and boxes that often architecture is dependent on… the idea of forms that didn’t have strict beginnings and ends was something that I thought we could capture.”

In a matter of months, the public will decide if Maltzan succeeded. Construction has been relatively steady — a few bumps here and there, as is perhaps inevitable with a project of this scale, but nothing insurmountable. PCL construction is expected to turn the site over to the WAG and its team of Inuit curators next summer.

They will be ready. For years, Borys has eagerly gauged the level of interest in the project; he is regularly peppered with questions from intrigued visitors, he says. Now, as the project shifts into its home stretch, it is beginning to give its own answers, revealing the ways it will alter Winnipeg’s streetscape for generations to come.

And architecture, Maltzan believes, is fundamentally about those relationships: the ones buildings have with the street, with each other, with the people who use them. For years, he has carefully envisioned what the Inuit Art Centre’s relationships will look like, but now, they are coming into the public view.

Over the years, he adds, architects learn to be patient. Still, there’s a thrill as the completion draws nearer, too.

“Architecture is fundamentally about the building,” he says. “You can talk about it, but it’s not until it’s finally physical and out in the world that you get to start to see the true nature of what the design does, how it’s working and what it is. To finally see that happening, it’s pretty exciting.”

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Mike Deal started freelancing for the Winnipeg Free Press in 1997. Three years later, he landed a part-time job as a night photo desk editor.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.