Raising their voices The WAG's Inuit Art Centre will be about people, not just things they create

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 16/12/2016 (3285 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

This is the second of a two-part series investigating the impact the Winnipeg Art Gallery’s Inuit Art Centre, with the world’s largest collection of Inuit art forms, will have on Winnipeg and on the Nunavut commnities that have filled the WAG’s vaults for generations. Read Part I, which looks at the Inuit’s often painful history and how it is beautifully told through art.

It’s mid-November, and Stephen Borys is sitting in a large leather chair in his second-floor office at the Winnipeg Art Gallery, enveloped by limestone walls and history.

Inside and out.

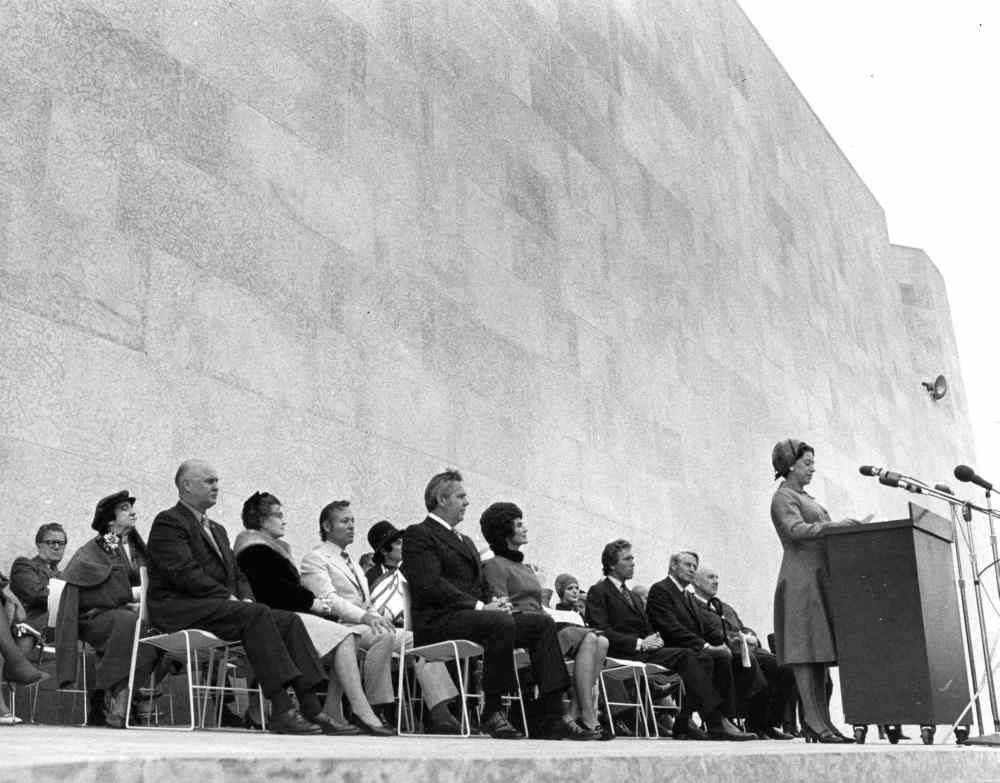

After all, when Her Royal Highness Princess Margaret opened the WAG on Sept. 25, 1971, Winnipeg architect Gustavo da Roza’s arrowhead design — described as a ship’s prow pointed north — was heralded as both "bombastic and brilliant."

In two years, give or take, that ship will have a new stern — the four-storey, $65-million Inuit Art Centre that Borys — the WAG’s director and CEO — calls "a gallery for the 21st century," and a means to redefine the template of the now-104-year-old institution.

Borys believes galleries and museums must start asking themselves new, inward-looking questions. Why is the WAG here? What difference is it making in people’s lives?

“We always figured those were United Way questions," says Borys, who has been at the ship’s helm for the past nine years. "But more and more museums have got to rethink what their place is in the community and what their impact is. Not just because of taxpayers’ dollars. We want to be meaningful, we want to be relevant.”

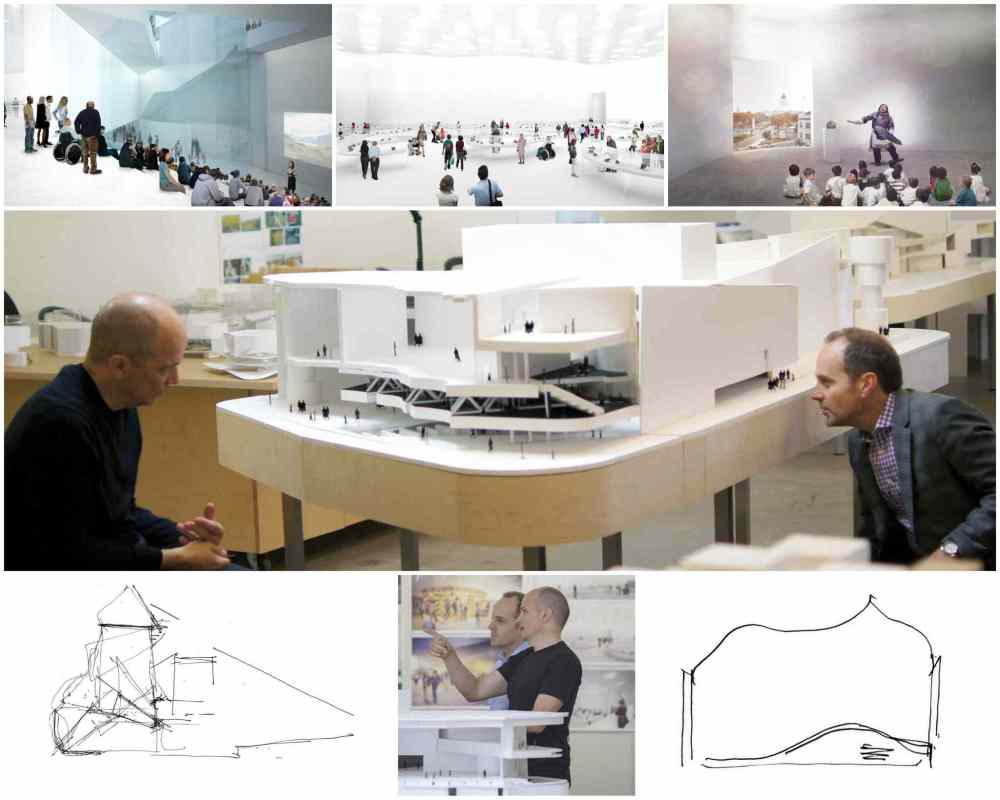

The WAG is about to get that rare chance. In the spring, ground will be broken for the IAC, which will become home to the more than 13,000 pieces of Inuit art already in the gallery’s possession. The building, designed by award-winning Los Angeles-based architect Michael Maltzan, is scheduled to open by early 2020.

Naturally, such an ambitious project evokes some trepidation, even after decades of fundraising, planning and false starts.

But Borys has seen the architectural renderings: Maltzan attempts to capture the light, vastness and scale of the North. He has confidence the IAC will do justice to the WAG’s cutting-edge architectural history.

“I no longer lose sleep over the art centre building," Borys says. "It’s going to be a spectacular, world-class building. That’s going to happen.”

Programming for the centre, already well underway, includes virtual tours, in-studio demonstrations and live performances.

“But what keeps me up at night," he says, "is whether the Inuit voice is the first thing you hear. That’s going to be critical. You know, we’re calling this an Inuit Art Centre, so that could mean 100 different things to 100 different people. We have to make sure if we can deliver on that."

You see, it’s not just about delivering the art. If only it was that easy.

It’s about telling the story of an isolated people whose history — how they’ve lived, how they’ve struggled, how they’ve survived — has largely been told in the images produced by their hands and imported south, not by their voices. Which is why the mission of the Inuit Art Centre is grounded in the spirit of reconciliation.

That’s what fuels the WAG director’s insomnia: will anybody hear?

“When this building opens, what if that 12-year-old kid comes in and says, ‘So what?’ We’ll have missed something huge… And it’s not just the 12-year-old. Whether it’s Inuit elders, Inuit artists, WAG members, scholars, students — what will it mean to them? Will it be that ‘wow’ moment?”

Hopefully. A moment more than 65 years in the making.

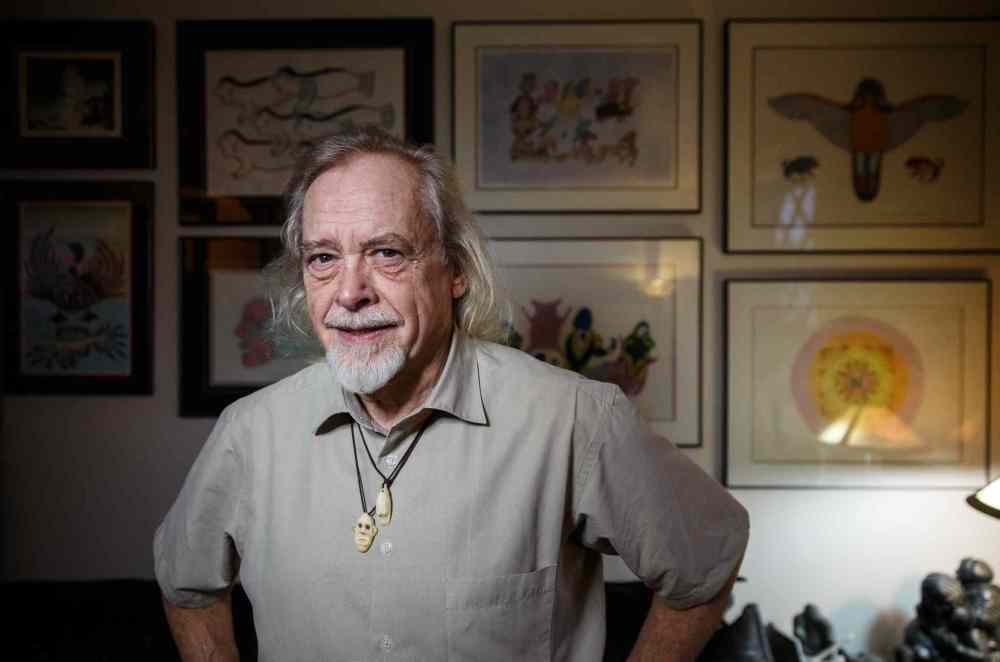

For almost 30 years, Darlene Coward Wight’s office was a vault in the bowels of the WAG housing an "encyclopedic collection" of Inuit art dating back to the late 1880s.

The shelves are stacked with carvings categorized by community, by individual artists. Thousands of them. There are more than 6,700 carvings alone.

The drawers contain boxes with delicate bone carvings that the Inuit would trade with European whalers in exchange for a precious possession: sewing needles. There are carvings of whale bone hundreds of years old.

“It’s hidden," says Wight, the WAG’s longtime curator of Inuit art. "People know we have 13,000 pieces in our Inuit collection, so they come to the gallery and say, ‘Where are they?’

"Of course, we can’t put them all out. That’s why it’s so exciting. The Inuit Art Centre will have a visible vault that would allow us to put our stone collection, at least, in permanent view."

Indeed, the defining feature of the IAC will be a three-storey high (11.5 metre) glass vault that will hold the entire carving collection of the WAG. The vault will have the capacity to accommodate a collection double the size during a 25-year growth period.

"People will be able to see it from the street," Wight says. "We’ll be able to get this out of the basement where people can see it."

Wight calls her occupation a labour of love that began with her first trip to the North in 1981, shortly after graduating from Carleton University with a master’s in art history. Then employed by the Arctic Co-operative Ltd., she flew to Taloyoak, Nunavut (formerly known as Spence Bay) — a tiny village located 1,200 kilometres due north of Churchill — determined to meet the artists whose work she’d studied.

There was only one other passenger on that late-fall DC-3 flight and Wight still remembers his name: Eddie Kikoak, a resident of Taloyoak, who pointed out the muskox on the ground.

When she woke up the next morning, there was snow on her cot that had blown through a window covered by plastic. The hamlet’s children swarmed Wight, asking her name. She told them it was "Darlene," which they’d never heard before.

Wight travelled to the isolated village to meet carvers Judas Ullulaq and Maudie Okittuq before their work became staples in galleries and museums across the south.

"I wanted to approach the art the way I would approach any art form," she says. "I didn’t want to treat it as a craft or an ethnic curiousity; I wanted to treat it seriously. Art that was worthy of being put in museums. To do that, I thought I had to focus on the artists, not just make it about polar bear shows. I wanted to bring out who they were.

"So much that had been written about Inuit art up to that time was just sort of talking about subject matter and guessing about what it was. But I was determined to find out right from the artists."

Wight didn’t just ask questions. She went out on the land, camping and hunting caribou.

"It was like going to the moon," she recalls. "It was so fascinating."

Wight vividly remembers waking up one morning and looking outside the tent. They were surrounded by a herd of caribou. Guess what they had for lunch?

"That’s why I had to go north," she reasons, some 35 years later. "I had to meet the people and sit on the floor and watch them skin white foxes.

"The most important thing is to see the people behind the art."

Wight, who joined the WAG in 1986, has since made dozens of excursions to the Arctic, including a return visit to Taloyoak in the mid-1980s.

A young Inuit woman in the community introduced Wight to her baby girl. She had named her daughter Darlene.

• • •

Wight’s experiences only underline the continuing evolution of the deep relationship between the WAG and Inuit art that began, innocently enough, with the marriage of serendipity and shopping.

In 1953, Dr. Ferdinand Eckhardt walked into the bustling Hudson’s Bay Co. store at Portage Avenue and Memorial Boulevard and came upon an unexpected discovery.

Eckhardt, a Vienna-born art curator, had just been named director of the Winnipeg Art Gallery, which was founded in 1912 at the intersection of Main and Water streets and was the first civic art gallery in Canada. Inside the store, Eckhardt found a shop that sold small soapstone carvings, an art form he instantly considered fascinating and exotic.

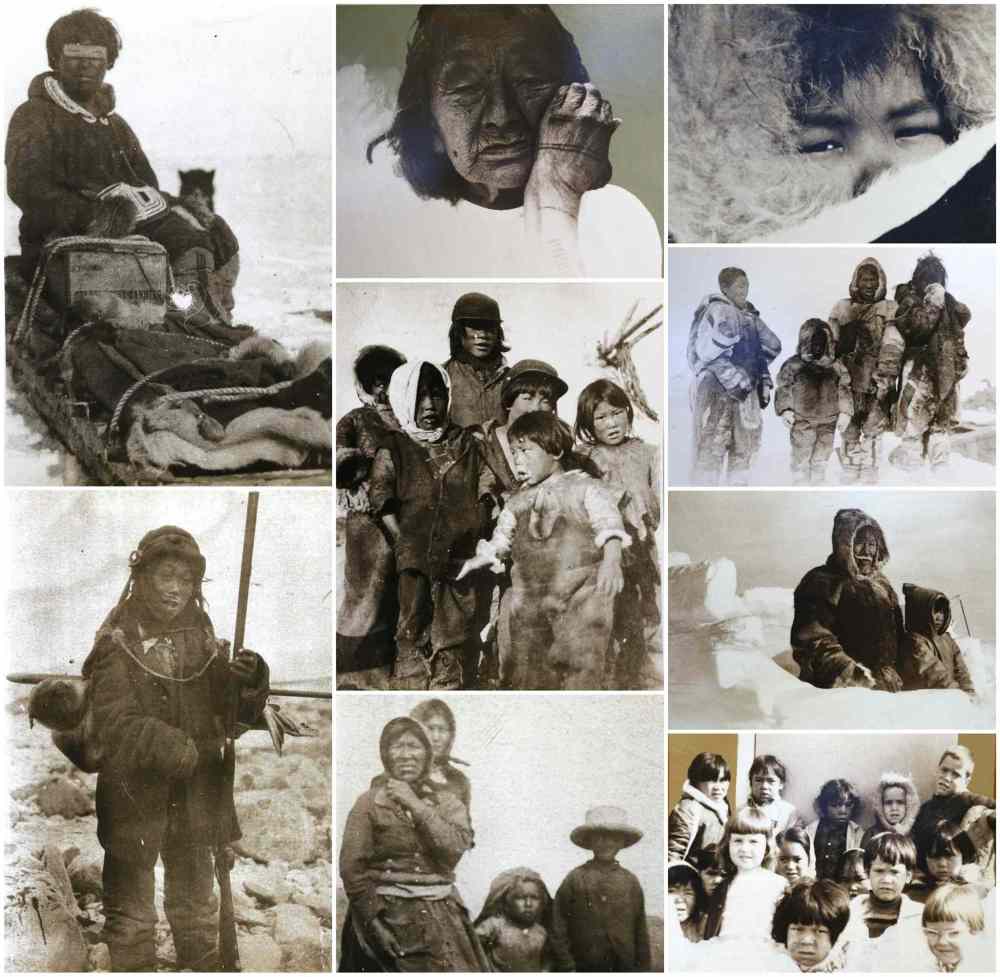

The carvings were the first exports of a fledgling federal arts-and-crafts program designed to provide, at minimum, temporary employment and means to the hundreds of Inuit families who were relocated — some estimates peg the number more than 6,500 — from the early 1950s to the mid-1960s. They were scattered throughout dozens of Arctic communities that, at the time, were little more than RCMP and Hudson’s Bay Co. outposts.

Each of the settled Inuit were given ID tags and Christian first names. Their children were forced into federal and residential schools. Thousands of their sled dogs were slaughtered, mostly by RCMP officers and federal officials.

The children were not allowed to speak Inuktitut in school, or face punishment. They were made to wear western clothing and learn English. If they didn’t attend school, their parents — who left the land to stay close to their children — were denied federal assistance.

In almost every way, the Inuit were trapped: struggling to adapt to an Anglo-based culture while facing the void left by centuries of a semi-nomadic existence living off the land.

Eckhardt, like the vast majority of Canadians, would have known little of the Inuits’ plight. Still, he immediately returned to the WAG, then located on Vaughan Street (now the Manitoba Archives building), wanting to know, "Why aren’t we collecting these things?!"

It was only the beginning. Within a decade, wall hangings and printings depicting the Inuit life story flooded south.

“It was a very visual culture," Wight says of the Inuit’s innate ability to master so many art forms. "They didn’t really have a written language. So everything was memorized. Mythological traditions were handed down orally from generation to generation. Hunters literally knew what an animal looked like from inside out. And they were able to navigate on the land simply by looking, observing, seeing the ripples in the snow.”

So in a roundabout way, the concept of the Inuit Art Centre was born at the time of Eckhardt’s first trip to the HBC store. It just took a lifetime to gestate.

It was a natural fit from the beginning: the WAG just a few steps away on Vaughan Street and then directly across Memorial Boulevard from the Hudson’s Bay store, the early trader in Inuit art imported south; most air travel to the North went through Winnipeg; over time, the gallery acquired thousands of pieces donated by local collectors.

Since Eckhardt’s first purchases in 1953, the gallery has amassed the world’s largest collection of Inuit art, now more than 13,000 pieces. Another 7,300 works are on loan from the Government of Nunavut for five years. The WAG has presented more than 160 exhibitions and published some 60 Inuit art catalogues.

“We have the collection, we have the exhibition records, the publication records, we have the outreach with the North," Borys says. "So for some reason we feel there’s a justification, there’s a responsibility.

“On the other hand, this is a whole new game. Because Inuit art as you know it, as I know it, has been largely curated, presented, documented by non-indigenous people. This is the big chance for us to do it right — to actually rethink the template.”

In fact, the WAG began studies on establishing an IAC more than two decades ago, but things never went beyond the planning stage. Borys says the difference this time was a perfect storm of readiness — from the WAG, the Inuit community and the city — combined with the cultural recommendations of the federal Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

“This fit right in,” he says.

Besides, Borys says, there is no major gallery or museum in Canada currently focusing on indigenous culture, a fact he calls "incredible."

Charlene Bearhead, education lead for the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation at the University of Manitoba, believes the IAC will play a unique role in the healing process for both Inuit and for other Canadians, most of whom aren’t aware of that community’s miserable history: forced relocation, residential schools, federal government-issued ID tags with numbers, not names.

"Education is reconciliation," says Bearhead, who also serves as a consultant for the WAG’s indigenous art initiatives. “What’s really amazing about the potential of this (centre), it gives the Inuit an opportunity to see themselves, to express themselves. To voice what they believe non-indigenous people need to know about them. But also a place to take their own children and grandchildren.

“The most important thing about the programming and education is that it comes from Inuit. It comes from the communities, it comes from the knowledge keepers, it comes from the families. That’s key in all of this. Because that was the problem when we look at education as reconciliation: When other people outside First Nations, outside Inuit, outside Métis (took charge).

“What’s really important is that it doesn’t matter what I would like to see," Bearhead concludes. "It matters what Inuit would like to see, and their children would like to see of themselves. And they will know what that is.”

Rachel Baerg, the gallery’s head of education, said the WAG has been working with several stakeholders — artists, Inuit elders, the Manitoba Inuit Association, the provincial Department of Education — to design programs ranging from theatrical productions to virtual tours.

The IAC’s entire second floor will be dedicated to education, including a 100-seat theatre and five state-of-the art studios.

“I would like to think of this as a living museum; a breathing, vibrant, active museum," Baerg says. "When I think of the IAC, I think of a centre that will be lit up day and night, where people will be coming and interacting with the art in different ways.

“We have the opportunity now to do this right, and create a much more empathetic, perhaps, society. Where we can reflect on the positive and not-so-positive aspects of our history.”

Baerg sees the IAC as a global classroom. In January, for example, the WAG will be holding its first virtual tour of its current Our Land exhibition — a collection of Inuit work on loan from the Nunavut government.

The pilot project — a collaboration between Cisco, TakingITGlobal and Connected North technology firms — will include a live 45-minute tour seen by students in Arviat, Nunavut, Brampton, Ont., and Vancouver.

In the future, Baerg says the IAC will be able to record and offer virtual tours, or elders’ storytelling, or curators explaining how art is displayed to classrooms "from coast-to-coast" and throughout the North.

“We want to have a broader conversation about Canada and its history," she says. "For so many years the North has been isolated. It’s time that we embrace and learn that education.

“I think, in the past, museums and galleries have been seen as exclusive places," she adds. "Places for people who are scholars, people who have money. We want to change that. We have the opportunity to make it more inclusive. That means rural communities, that means new Canadians, that means indigenous people who may never have felt welcome in this space.”

Over time, WAG officials plan to hire more Inuit staff to deliver that message of inclusion.

Fred Ford, the president of the Manitoba Inuit Association and WAG board member, contends that every indigenous exhibition the gallery produces now contributes to the healing process. The IAC can only amplify that effect.

"To bring in people to talk about their own work as artists, and not have anybody speak for them… that’s an act of reconciliation," says Ford, whose Inuit heritage stretches back three generations.

"Those stories need to be heard. I mean, in order to reconcile you need to know what happened. And the Inuit experience was very different from people from First Nations — similar, but different. The stories about relocation and the impact of the families being separated. The Inuit Art Centre will tell those stories.”

Ford relates an anec of American anthropologist Margaret Mead who, during her studies, expressed an urgency to reach a community before the oldest living person there died. Before their stories, their myths, their knowledge was lost forever.

Ford is reminded of that urgency when it comes to the Inuit Art Centre.

"If we had invented a writing system or had the luxury to write our story, it would have been done in a very eloquent way," he says. "This (centre) does that; the caribou crossings and a lifestyle that was in harmony with nature — not that long ago.

"Stories that need to be told to young people for them to take ownership, an incredible story of survival and being a part of the Canadian fabric."

Adds Wight: "There’s such interest internationally in indigenous peoples now. Not just Inuit. So I think we’re really on the cusp of something amazing, just as the world is opening up and becoming more interested, hopefully, before the culture disappears."

Wight, the curator, is referring to the declining number of traditional artists and a past lifestyle that that has been largely dwarfed by technology and assimilation. Yet it’s just as clear the Inuit will to pass on those traditional values isn’t vanishing.

It’s not dying. It’s evolving.

Victoria Kakuktinniq always knew she wanted to sew, just like her mother and sister.

But sports and high school at Rankin Inlet had consumed much of her time until her late teens, when the urge became too strong.

Kakuktinniq took a five-month course in traditional Inuit sewing, learning to make kamiks (footwear usually make from seal or caribou skin) and amouti (a specially constructed parka with a baby pouch on the back).

Immediately, Kakuktinniq realized, "This is what I want to do with my life. I wanted to take it to the next level."

So she did.

Mere months after graduating from fashion design at MC College in Winnipeg, Kakuk moved to Iqaluit, the Nunavut capital, and began selling a few of her custom-designed sealskin parkas over the Internet early in 2014.

Kakuktinniq hasn’t stopped sewing since. She has sold more than 600 parkas —all stitched with her own hands — and hundreds of mittens, headbands and broaches in the last three years.

Her business, Victoria’s Arctic Fashion, has been all-consuming. Her exclusive products aren’t cheap, either: a sealskin parka sells for $2,400, mittens are $240 a pair.

Still, using only a Facebook page (her website is just a few weeks old), orders keep pouring in. Who’s buying? "Everyone," she says, from her home/studio in Iqaluit. "From all over Canada."

But for the 27-year-old Kakuktinniq, her passion was never just about business.

"Some people say our language is dying, our culture is slowly fading away," she explains. "But because it is, there’s so many people trying so hard to prevent it from dying. There are so many young artists who are sketching and drawing and bringing back the traditional art and culture. Throat singers, performers."

Kakuktinniq is far from a lone wolf in the Arctic. Iqaluit has become a spawning ground for a new generation of young artists.

"Everybody is inspired by everybody else," she notes. "There’s concerts and trade shows. Everyone is trying to promote culture and keep it alive, to gain as much knowledge as we can from our elders so we can continue to share and understand."

At a recent trade show in Rankin Inlet, the tables in the middle-school gymnasium were populated by as many 20- and 30-somethings as elders.

Keenan "Nooks" Lindell, 26, was displaying his hand-crafted "pana" — snow knives used to cut blocks to build igloos. They included the "Thorogood Chopper," which he designed while blaring the George Thorogood song Bad to the Bone.

"It’s really a good way to connect my family again," Lindell says of his creations, which feature handles of caribou antler and muskox horn. "I’m asking my grandfather. I’m asking my uncle. I hand out (his pana designs) at the elders centre and show them everything and ask them to critique it."

Lindell, his wife Emma Kreuger and friend Paula Rumbolt were also selling a line of clothing — scarves, dresses, leggings — all with traditional patterns from sealskin to ulus (cutting knives) to traditional Inuit tattoos.

The trio created their fledgling company, called Hinaani Designs, after attending an entrepreneurial course.

"This," says Lindell, a substitute teacher, "is our first big test."

Again, the concept is not just about selling leggings. The Hinaani website also has how-to blogs on traditional skills, such as drying caribou.

"So you’re kind of bridging the gap between elders and kids on their iPods, showing kids that Inuit culture is cool. And it is cool," Lindell says.

Adds Rumbolt, 26: "It (the Arctic) is where we come from. We want to show our pride and we want people to be able to wear it every day. It may be a few years down the road, but for now it’s a nice side project."

Sherri Van Went, the WAG’s retail operations manager, says sales of Inuit carvings alone at the gallery’s two gift shops — including the WAG at The Forks, which opened last May in the Johnston Terminal — have increased 500 per cent since 2012. The sale of all Inuit art has increased tenfold.

"I don’t know what the numbers (of artists) are now compared to what they used to be," Van Went says. "I know that there’s less. But I still meet people who’ve learned from their grandparents or their parents and they’re in their 30s. So I do see young people using traditional skills.

"I’m consistently blown away by the work that comes through our door. I think there’s still a lot of room for hope. It’s not going to be the same as it was, but nothing is anywhere. Everything changes.

"Like artists anywhere, they’re coming up with new and interesting ways of creating and expressing themselves. There’s lots of room for growth."

For example, Van Went cites the work of Adina Tarralik Duffy, a Coral Harbour jewelry-maker and founder of the design company Ugly Fish, who fashions earrings out of beluga whale vertabra discs and seal claws, and pin cushions made of sealskin.

Designers such as Kakuktinniq and Duffy are redefining Inuit fashion using the same traditional skills, Van Went says. And consumers are responding.

"What I’ve experienced is that people, in general, are embracing things that are handmade, that are one-of-a-kind, that tell a story," Van Went says. "People are looking for quality and authenticity."

But the resurgence of Inuit culture hasn’t been confined to sealskin and soapstone.

Tanya Tagaq, a throat singer from Cambridge Bay, won the Juno for Aboriginal Recording of the Year in 2015. Filmmakers such as Alethea Arnaquq-Baril, whose documentary Angry Inuk defended the seal hunt as a vital means of sustainability in northern communities, are reaching mass audiences.

The software company, Pinnguaq, based in Pangnirtung, is developing games and digital experiences designed to "push the limits of technology and cultural expression." One project in development is a survival game centred around the mythical Qalupalik sea monster — a creature with long hair and fingernails — who kidnaps children who get too close to the ice.

Yet, there remain human touchstones to Inuit culture in each community.

In Baker Lake there are Hugh and Ruth Tulurialik, artists and musicians in their 70s who have performed from Nunavut to New York. Hugh is described as an "inumariq" — meaning a "real man" in Inuktitut — who still goes to local schools to teach children how to make igloos and kayaks, or skin caribou and gut fish.

"If they like to do it," he says, "I will teach them."

Tulurialik, 72, can play the accordion, keyboard and guitar. And if he hears word of a caribou herd near Baker Lake, he’s out the door.

In Rankin Inlet, there is Levinia Brown, now 69, who was delivered by her father on the open tundra near Whale Cove, on the western shore of Hudson Bay. "We were on the dog team when my mother went into labour," Brown explains.

That baby girl born on the land grew up to become the first female mayor of Rankin Inlet, and later the deputy premier of the Nunavut government.

Brown raised 10 children. And her wall hangings have graced the Canadian Museum of Civilization across the Ottawa River from the Parliament Buildings, and galleries in Russia, Japan and the United States.

"Art is like a university, an education," she says, sitting in a living room filled with family photos. "I can sit for hours. It reminds me of my childhood. I think about my family and my marriage… what can I do better? It’s almost like praying, I think."

That’s the complexity of Inuit art, and not just what it means to the people who perfected the craft. It could mean something so profound as the bond between animal and man.

It could mean something as practical as a young man from Baker Lake named Noah Noah, whose caribou carving pays for some groceries and a few packs of smokes.

It could be a 27-year-old designer such as Victoria Katuktinniq, with dreams of someday showing her parkas on the fashion runways of Milan and Paris.

Or Inuujaq Fredlund, a 32-year-old seamstress from Rankin Inlet who spins muskox wool (qiviut) into scarves and tuques. "It’s almost like a rite of passage growing up. That’s how I was raised," Fredlund says.

The art of Inuit takes a lot of forms. So, too, do the artists.

Turns out, if you’re coming to kidnap their aspirations, you’re going to need a bigger Qalupalik.

Back in the WAG basement, Darlene Coward Wight is telling the story about the Inuit mythical times when animals and humans lived together, and understood each other’s language. In the shamanic lore, all living beings have a soul. So taboos always existed about not angering the souls of animals killed on the hunt.

There was a sea creature, too, usually a woman, who controlled the supply of fish and seals. The sins of the humans would catch in her hair, so the shaman would come and braid it, and the sea creature would release the animals.

The Inuit have also experienced first-hand the sins of the humans: Relocation. Residential schools. The unforgiving attempts by a federal system to change their names, their identities, their belief system, their language.

Their hair is full.

One building, no matter how shiny and well-intentioned, will not wash away decades of colonization and mistreatment. But it’s a new beginning, Borys believes.

Recently, a donor asked the WAG director a fair question: Would his new Inuit Art Centre change the quality of water in Iqaluit? Borys mulled it over for a moment.

“I said, ‘yes,’" he recalls. "Because artists are producing prints on the impact of mines on the water. Artists are doing carvings about abuse, about alcoholism, about the school system. And we’re showing those images and… people are understanding it.

“We’re exposing much more than the art form. We’re exposing the way they live, their values. We’re looking at their histories."

The WAG now attracts 125,000 visitors annually. When the IAC opens its doors, the number is expected to rise to 200,000.

“The fact that it (Inuit culture) is going to be front and centre for every school kid, every visitor, tells us that the Inuit story is going to be told over and over here," Borys adds. "And it’s going to be told with a new honesty, a new authenticity, because it’s got to be supported and grounded by the Inuit.

“If the Inuit Art Centre becomes a mouthpiece, a forum, for that type of dialogue, I think we’ll have succeeded.”

To artists such as Levinia Brown, the centre means history. Heritage. A way of life preserved.

Just the thought of displaying thousands of pieces of the Inuit story under one roof — even if the opening is at least two years away — is reason enough to hope.

No, it may not be heaven for Brown, but it will get her a little closer.

"I will be on Cloud 9," she says. "That’s going to be good for all of Nunavut. And the whole world."

Then she goes back to tending to her granddaughter, Nathalie.

The next seamstress waits.

randy.turner@freepress.mb.ca Twitter: @randyturner15

About this project

Ground will be broken on the WAG’s Inuit Art Centre in 2017. The ambitious project, which will feature the world’s largest collection of Inuit art forms, is scheduled to open in 2020. In anticipation, the Winnipeg Free Press wanted to investigate the impact the centre might have, not just on Winnipeg but on the Nunavut communities that have for generations filled the WAG vaults.

In Part I, the Free Press looked at the Inuit’s often painful history and how it is told through art. Part II focuses on the Inuit Art Centre’s mission, and how those behind the project believe it will redefine the role of galleries and museums.

Randy Turner

Reporter

Randy Turner spent much of his journalistic career on the road. A lot of roads. Dirt roads, snow-packed roads, U.S. interstates and foreign highways. In other words, he got a lot of kilometres on the odometer, if you know what we mean.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.