Northern Stars Inuit carvings, jewelry and wall-hangings are not just pieces of art; they're stories - some thousands of years old - spoken by hands

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 09/12/2016 (3292 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

This is the first of a two-part series investigating the impact the Winnipeg Art Gallery’s Inuit Art Centre, with the world’s largest collection of Inuit art forms, will have on Winnipeg and on the Nunavut commnities that have filled the WAG’s vaults for generations. Read Part II, which focuses on the IAC’s mission and how those behind the project believe it will redefine the role of galleries and museums.

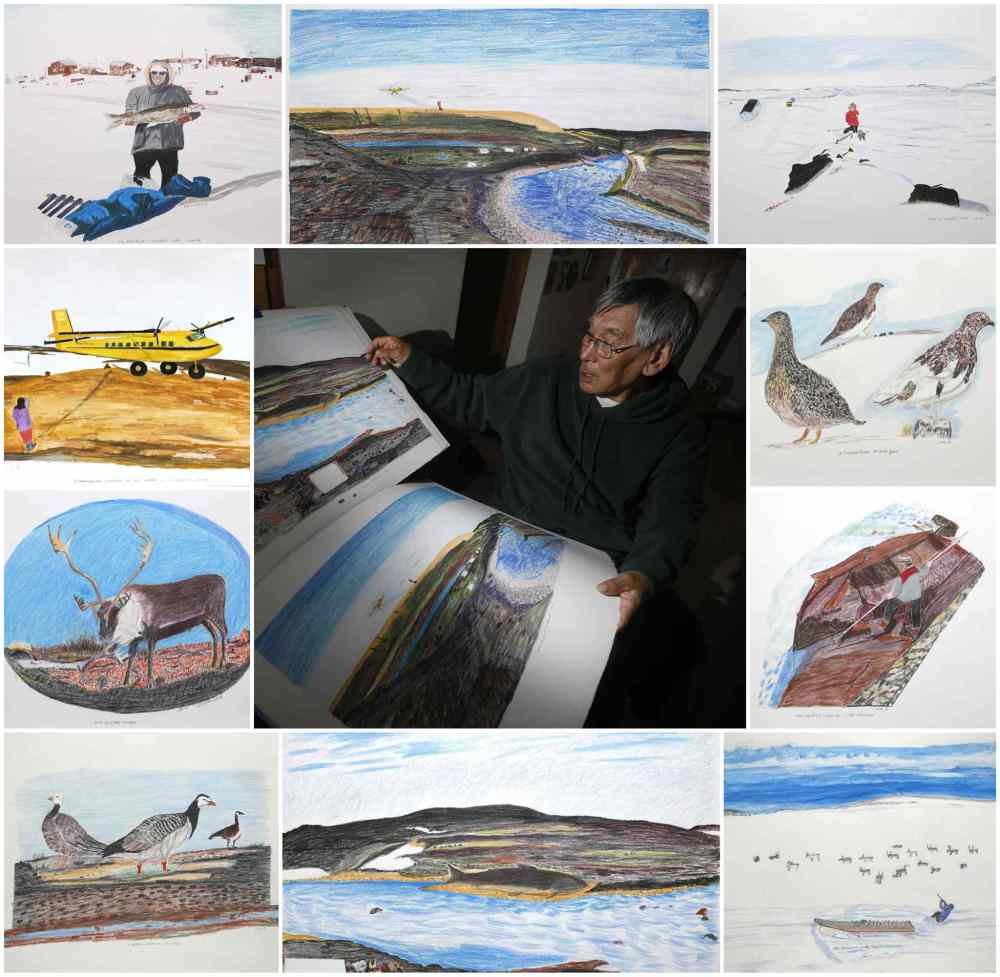

RANKIN INLET — Noah Tiktak has these brown, smiling eyes. They light up when he talks about the generations of his family — his father, his daughters — who have told the story of the Inuit using their voice, their hands, their paint.

“Art is in my blood,” he says. “It’s who I am.”

Tiktak, now 55, is seated in a small shack just outside his home in Rankin Inlet, where he comes to create his jewelry and dancing drums. It’s late September, and the weather is starting to turn in the Arctic community, on the northwest shore of Hudson’s Bay.

In that shack, Tiktak tells of two experiences that synthesize the brutally beautiful existence of an Inuit people steeped in mysticism, mistreatment and, ultimately, an innate desire to tell their own stories.

The first: While serving as a counsellor at a youth camp years ago, Tiktak was taught how to drum by an elder. It was in a small tent, holding about 25 mostly young campers, and everybody took a turn.

As a boy, Tiktak remembers being too small to hold up a drum, but he would try anyway. His late father, John, a well-known soapstone carver, would help by holding up one end of the instrument.

When it was Tiktak’s turn to take the drum, he was nervous. All these strangers. And then…

“Everybody disappeared in the tent,” he says. “Who popped up? My uncles and aunties. My grandparents. And I’d never seen them. They passed on before I was born. But I recognized them. They’re smiling, they’re happy, they’re singing.

“That’s the best high I’ve ever had in my life. It was nothing to do with Shamanism but… powerful. I was the happiest man. And then when the song ended… where am I? I’m back to reality. But I’m smiling away. That was the best thing ever.”

The second story: Tiktak is a boy in grade school. Like other Inuit children, he must attend a school operated by the federal government. If not, his parents won’t receive a children’s allowance.

He remembers the teacher’s strap was burgundy, about five centimetres wide. He remembers one classmate, a girl, being dragged by her braids for a minor infraction.

“They tried to make sure we didn’t use our language in school,” he says. “Anything I said in Inuktitut, I’d get punished. Imagine a Grade 2 child or a Grade 1 child getting the rubber strap or getting hit (because) he just didn’t understand a foreign language, a different way of living.”

Mostly, he remembers the pain in the faces of his parents, John and Atangat.

Tiktak’s mother died in 1977. His father passed in 1981. To this day, he breaks down when discussing a system that made his parents feel so powerless.

“They saw what was being done to us,” he says, wiping away tears. “They could do nothing. They were afraid of the officials. It bothers me because I know how much it hurt them.”

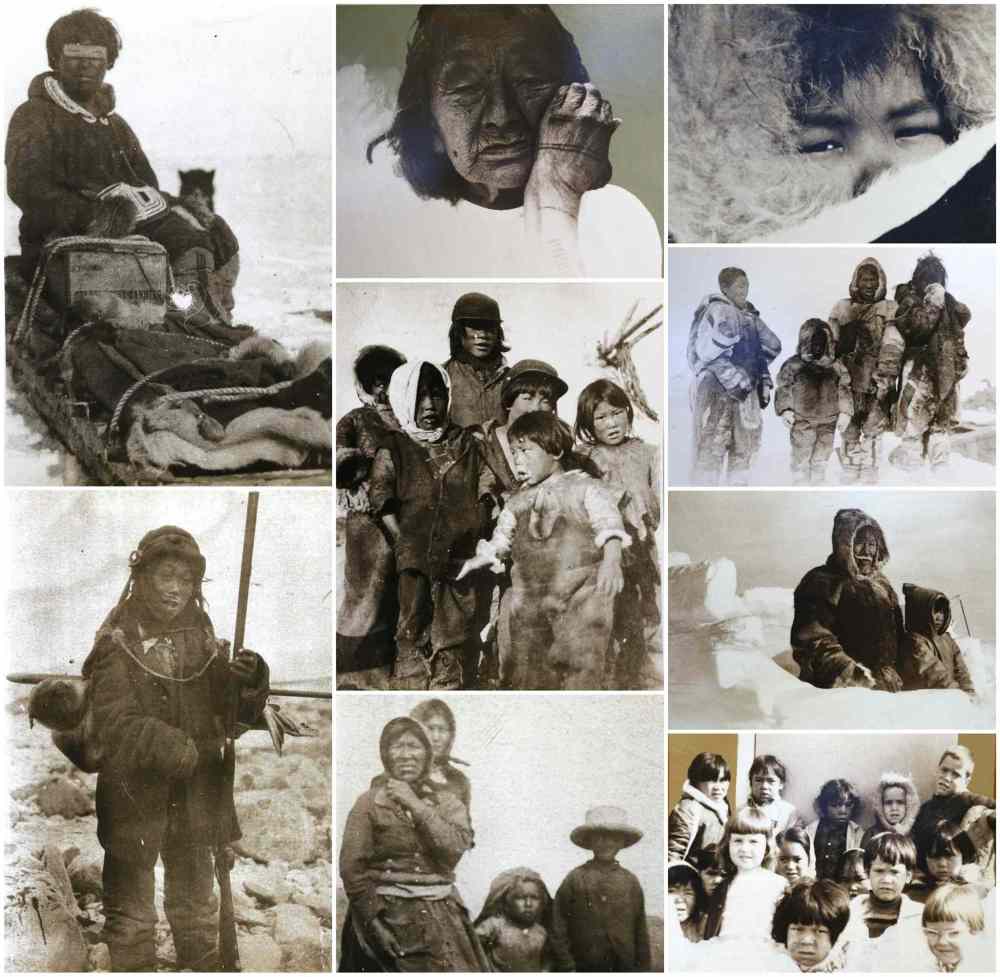

It’s not that the Inuit just didn’t have a voice. Most didn’t have names, at least not their own. To the federal government, they were numbers. Literally.

Under the Eskimo Identification Tag System, first implemented in the early 1940s — and abolished in 1978 — Inuit were given a letter (E for eastern, W for western), then a number for their community, followed by a personal ID number.

The numbers were engraved on a copper or leather disc, 2.5 centimetres in diameter, with a crown in the middle. If you needed medical attention, show your number. Federal assistance? Show your number.

Tiktak still has his disc, E3-1457. And he can still recite the numbers of his mother (E1-267) and father (E1-266).

In fact, one striking revelation of spending a week in Rankin Inlet and Baker Lake interviewing dozens of Inuit is how many have their identification numbers seared into their consciousness.

Yet, at the same time, Inuit scholars note how most Canadians aren’t even aware of a practice that critics long ago described as frighteningly dehumanizing. Non-Inuit often referred to the discs as “dog-tags.”

“It’s shocking,” says Heather Igloliorte, an assistant professor at Concordia University and research chair of Indigenous Art History.

“This is what blows my mind. We have this serialized history of categorizing people by codes and numbers, and that’s how they (Inuit) had to be known. But nobody knows that in Canada. It’s really like a hidden history.”

Relocation is just one aspect of the Inuit experience foreign to so many Canadians.

How many know, for example, that much of the commercial art being imported south for last the 60 years — soapstone carvings, wall hangings, print-making — was non-existent prior to the Second World War?

That’s right, the modern Inuit art movement was founded when some white guys started traveling around the Arctic promoting it as a new way to make a living in the late 1940s.

The Inuit don’t even have a word for art. Or artist.

Yet in a matter of years, men and women born in tents or igloos were being hailed in galleries all over North America and Europe. They became stars.

Igloliorte says the lack of general awareness of the Inuit story is largely a function of isolation and distance.

“We’re just not close to the North,” she says. “We are, geographically, so far apart.”

Tiktak would agree.

“We’re the forgotten ones,” he says.

Not for long, perhaps. Sometime in 2020, the Winnipeg Art Gallery is expected to open Canada’s first Inuit Art Centre, a four-storey, 40,000-square-foot building adjacent to the WAG’s downtown location. The $65-million project will be unprecedented, and WAG director and CEO Stephen Borys believes the centre will become a world-class beacon for showcasing Inuit art and culture.

The centre will be designed to link Canada’s Far North to the south. It will feature the world’s largest collection of Inuit art, studio space, performance theatre and, most important, the voices of Inuit telling their stories.

“This is going to be our Smithsonian for Inuit,” says Fred Ford, a former Baker Lake resident, WAG board member and president of the Manitoba Inuit Association.

So what kind of impact will the centre have on Winnipeg? The Inuit community? Or even on the way museums and galleries will have to reinvent themselves?

And who are these artists? How did the Inuit, without any formal training, produce works that to this day can sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars on auction?

To find out, the Free Press recently visited the communities of Baker Lake and Rankin Inlet for a week, speaking with dozens of artists, both young and old, in an effort to not only trace the beginning of the modern Inuit art movement, but look at its future, as well. Will it survive?

The result is a two-part series; this first instalment focusing on the artists of the North in their own environment and the second on the vision for the Inuit Art Centre, an ambitious mission to tell stories centuries in the making, most of which have been passed down from generation to generation.

Art is not just in Tiktak’s blood. It was in the blood of his father, a renowned stone carver who in 1973 became an elected member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts. And it’s in the blood of his daughter, Becky Okatsiaq, a painter.

The art is in the drums he makes in his little shed, which Tiktak uses to perform and express “who we are as Inuit.”

“I was just a number before,” E3-1457 says. “Now I’m a taxpayer. I have a voice. It’s a reminder for how far we’ve come being a number to governing ourselves and having a vote.

“The way we were treated back then… holy smokes. We’ve come a long way.”

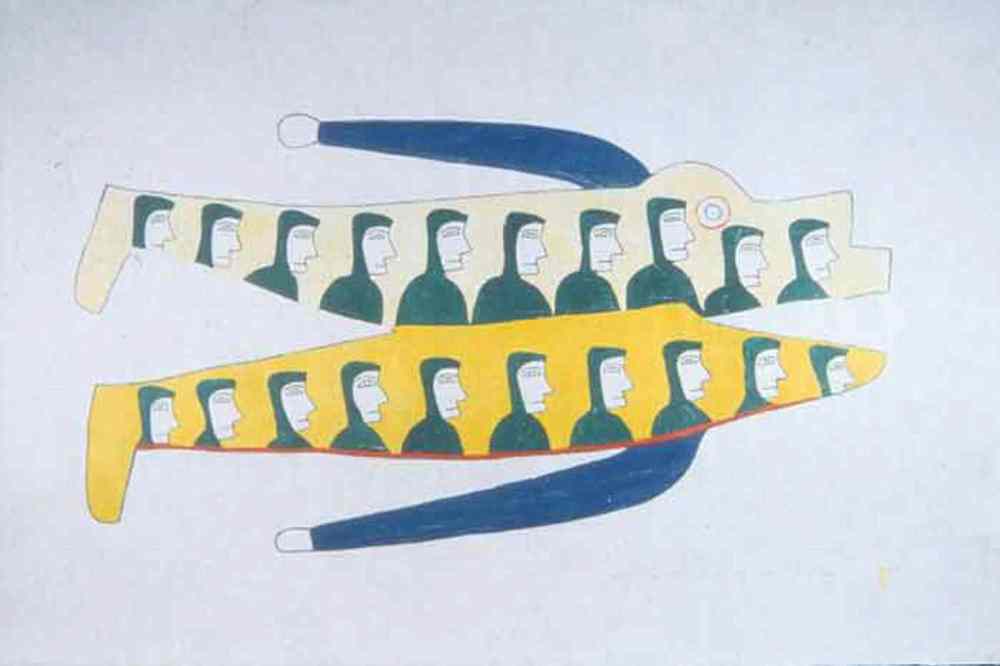

BAKER LAKE — It’s no small irony that the birth of the modern Inuit art movement arose just around the time Jessie Oonark almost died.

It was the mid-1950s, when Oonark’s family — who had hunted and fished for years in the Back River region, located deep in the heart of Nunavut (then part of the Northwest Territories) — was forced to split up and scrounge for food.

“My stomach was completely empty most of the time,” recalls Oonark’s son William, now in his 70s. “There were too many of us and (his parents) couldn’t feed us properly anymore.”

Forest fires had disrupted migration routes of the caribou in the area. Caches of meat had run dry.

William, about 10 years old at the time, said he and his siblings lived off dried sinew they found in caribou hooves lying on the tundra. “We would walk all day looking for them when the snow would melt,” he says.

Oonark and her youngest daughter, on foot in mid-winter, almost froze to death while attempting to reach a relative’s camp.

Eventually, the family would be reunited in Baker Lake, then a tiny inland hamlet that included little more than an Hudson’s Bay Co. trading post, an RCMP detachment and a few dozen Inuit families at the mouth of the Thelon River.

What transpired next for the Oonark family was a microcosm of the seismic cultural displacement experienced by Inuit over the next two decades, as the federal government systematically relocated a semi-nomadic people — who had for millenia survived on a lifestyle of hunting and fishing — into anglo-based communities.

They were assigned numbers. They were given Christian names. (For, example, William was originally named Noah by his mother and now goes by William Noah.) They were baptized by the Anglican or Catholic church. The children were forced to attend schools where Inuktituk was a forbidden language. Many were sent to residential schools in far-away communities.

“It was hard,” William recalls. “I was wearing caribou skin from head to toe and the next day I had to wear these western clothes with no heat. It was awful.”

Classes and communities were now composed of Inuit from several tribes, who William calls “strange people with different dialects.”

The majority of parents, such as Jessie Oonark, stayed in the community to keep close watch over their children. Without traditional means of seasonal hunting and trapping, Inuit became more and more dependent on federal assistance.

As a result, according to Igloliorte, where colonization of First Nations people in North America occurred over centuries, the Oonarks of the North faced such upheaval over decades.

“With the Inuit in the Arctic all of those same things, or similar things, happened in a really compressed time period,” she says. “So you had people that within a space of 30 or 40 years went from living entirely independently on the land to being settled into new communities.”

At the time, the federal government reasoned the Inuit required settlement for their own good, since many were facing starvation, which Igloliorte says represented the patrimonial attitudes of the time.

“They thought indigenous people needed to be cared for, even though they had survived in the Arctic for millenia,” she says. “It was like, ‘We know what’s best for you and now we’re going to do it.’”

Another reason for resettlement, critics have long contended, was over sovereignty, especially the disastrous relocations of Inuit families to the High Arctic in the 1950s.

“The Inuit,” Igloliorte says, “were like human flagpoles.”

Igloliorte, an Inuk from Nunatsiavut (northern Labrador), believes the federal government’s relocation motives were neither purely ulterior nor in the best interests of the Inuit. “Probably both,” she says, adding, “It’s complex.”

Regardless, the all-too-human experiment was past the point of no return. Not only had the Inuit been relocated, but thousands of their sled dogs — their primary mode of transportation for hunting — had been shot by RCMP and provincial police. (The RCMP claim the dogs were shot for health and safety reasons. Inuit elders contend it was to intimidate and disrupt their way of life.)

“You don’t hear about all this stuff, but that was part of how they were treated,” said Ford, whose Inuit grandfather, Henry Ford, operated and built the first Hudson Bay Co. trading post in 1915. “And they worked for a pittance for the Bay or police or the churches. Good little Inuit. The impact of that…

“So you’ve got this whole generation of people who were elders who knew where to be and how to live, how to make tools and how to survive,” added Ford, who returned to Baker Lake in 1980 to run the Igloo Hotel. “All of a sudden they were relegated to sitting in those old matchbox houses (a wooden house consisting of one 12-by-24-foot room provided by federal government). That was a poor life.”

The problem: Thousands of displaced Inuit now living in settlements with virtually no available full-time employment or means of financial support. So much time on their hands.

And that was the answer, perhaps. Their hands.

For centuries, the Inuit had been entirely self-sufficient, surviving in one of the planet’s most hostile environments because of their extraordinary ability to make almost anything — shelter, clothes, sleds, tools — with their own imagination and two hands.

“Artistic genius isn’t created out of the blue,” says Marie Bouchard, who moved to Baker Lake in the mid-1980s after completing a master’s degree in Canadian art at the University of Manitoba. “It seems like these artists became stars overnight, but that’s not the case.

“They have years and years and years of honing their traditional skills; in cutting patterns for clothing, in sewing, in designing. Fashioning tools by hand. They learned how to choose the right materials for the right project.

“As part of their esthetic, everything that they made, although functional, had to be beautiful,” added Bouchard, now community grants associate at the Winnipeg Foundation.

“And it had to be distinct. You could tell at a glance where someone was from based on the design of their parka. And then you could look at it more closely and think, ‘That’s how so-and-so does her caribou skin trim, or how she combines colours.’

“But that took years. The women started sewing at a very young age. That accounts for their amazing ability, once they were introduced to new materials, to be able to produce art.”

Bouchard, who now lives in Winnipeg, spent 11 years in Baker Lake, eventually starting a sewing co-operative with her husband after the federal government closed the community’s local operation.

In 1986, she curated an exhibition of Jessie Oonark’s work for the WAG, and has since produced other Inuit art essays, exhibition catalogues and shows, in addition to her work as a historian.

It’s somewhat ironic that there is no word for art in the Inuk language. They call it “visual expression.”

The men were experts at spacial reasoning. They had intimate knowledge of their surroundings and the animals they hunted. Memory was key to survival. Nothing was written down.

“They had to make their own sleds, their own kayaks, their own mittens, their own parkas. Everything,” says Baker Lake businessman Boris Kotelewetz.

When there was no wood on the tundra, Inuit would use frozen fish wrapped in caribou skins for sled skis. Then they would eat the fish after arriving at their destination. “It shows you how inventive they were,” Kotelewetz says.

After all, the Inuit had made carvings of walrus ivory with whalers dating back to the 1880s.

So when pioneering artist James Houston, who lived in the Arctic after returning from the Second World War, began bringing Inuit small carvings south in the late 1940s and early ‘50s, it convinced federal officials to introduce “craft officers” into the new Inuit settlements.

“When (federal officials) were looking for an industry to introduce, they realized that they could use the art market as one way they could possibly help the Inuit to regain self-sufficiency,” says Igloliorte.

Kotelewetz, 75, is a businessman now. His companies include a lodge, an earth-moving business and charter air service. The walls of his lodge office feature a collage of photos of Inuit and artists stretching over a century.

But back in 1966 he was a free spirit who arrived in Baker Lake as an arts-and-crafts officer after serving with the Exhibition Commission that marketed Canada to the world.

First impressions?

“It was mostly tents and igloos,” he says. “The biggest thing I learned when I came here was how much the government didn’t know about the country and the people. The intention was good, but a lot of times it didn’t turn out to be the best.”

Notwithstanding the myriad harmful, force-fed policies that would leave generational scars still visible to this day, the establishment of arts programs in the North was an unqualified success, almost immediately.

In Baker Lake, Oonark was given coloured pencils and paper in 1958 by a biologist named Andrew Macpherson, says Bouchard.

Already in her 50s, Oonark was a natural. Within a couple years, her drawings — mostly images of a lifetime in Back River country — were in print collections in the south, then around the world.

When Kotelewetz arrived in the mid-’60s, he provided Oonark with a studio. He provided her with more materials, markers and paint.

“I just turned her loose,” he says. “There was no stopping her mind. I gave her the freedom to explore herself.

“When I saw her work, I thought, ‘Holy crap, man!’ You could go to school, but you couldn’t learn that. You have to have a born sense of that.”

Oonark became one of the first true stars of Inuit art. Her work appeared in galleries and publications around the world. The money she earned mostly went to raising her 13 children.

But Oonark never moved away from Baker Lake. She died in 1985, one year after being made an Officer of the Order of Canada.

“She just stayed the same Jessie that she was,” Kotelewetz says. “She was a real character. She liked lingerie and thought they were classy dresses.”

And she oozed of confidence.

“There was a mountain of it. You couldn’t move it,” he says.

When Oonark travelled south to the big cities where her art was being exhibited, hosts expected her to be in awe of skyscrapers and waited for her reaction.

“Your air stinks,” she sniffed, at least once.

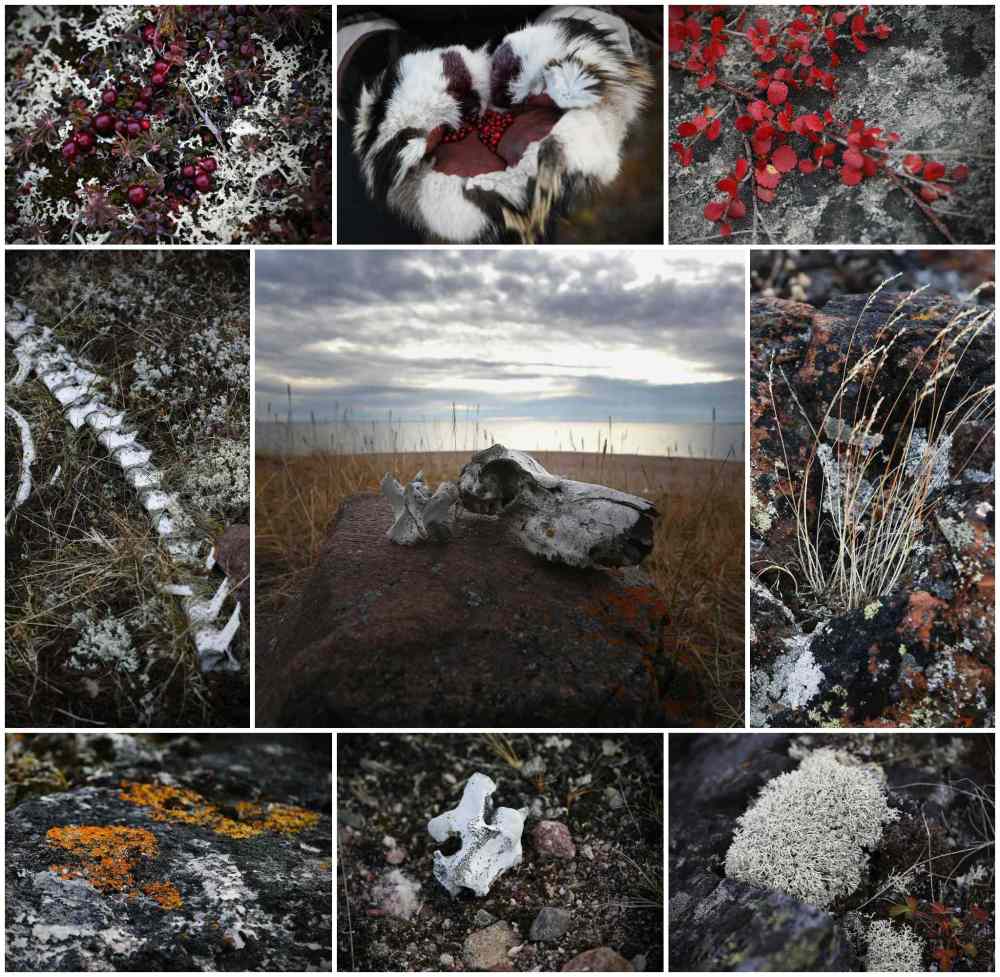

It’s an unusually warm evening when Salomonie Pootoogook ventures to his work table behind his wood-framed home to begin carving a five-pound hunk of soapstone into life.

Pootoogook (Big Toe) is 62 years old. The first question he’s asked: How did he get here?

He smiles before replying.

“Because of the girl, that’s why. She brought me here. It’s always a girl, right?”

The girl is Polly, his wife. Together, they have raised five children in Baker Lake, now home to about 2,000 residents.

The days of tents and igloos are long gone. There are modern schools, government offices (one has the only elevator in town) and the two major retail outlets can provide most anything offered in the south. The Internet can take care of the rest.

There’s even a Tim Hortons coming soon to the Northern Store.

But some things never change. Baker Lake is still populated by dozens of working artists, the second and third generations of the original pioneers.

Pootoogook’s only source of income is from his carvings, a trade he first learned in 1980 on Cape Dorset — long a treasure trove of Inuit artists on the southern tip of Baffin Island.

Over the next two hours, Pootoogook meticulously transforms the rock into a polar bear while the sun sets over a barely rippling lake. The stone bear will net him $100 from someone who works at the nearby gold mine. Some pocket money.

Pootoogook is seated on a wooden chair, his feet planted in a bed of splintered rock and antlers, remnants of other carvings. His tools are electric chisels and grinders that produce a fine green powder that floats away like smoke.

And it leaves green splotches on parts of his face not covered with goggles and mask. One tooth is green.

He says the rocks, their shape, tell him what they want to be. Picking up another nearby chunk of soapstone, he declares: “It’s a woman. I can see it.”

He has five children to feed and realized many years ago, “no work, no money.”

Next door, Fanny Avatituq is sitting on the floor of her living room, stretching out a square of black felt that will become her latest wall hanging.

She has yet to decide what objects she will incorporate into the image. Maybe polar bears, maybe swans. Then Avatituq will painstakingly embroider a colourful background and frame. She can spend weeks on one wall hanging.

“I don’t mind,” she says. “It’s something to do instead of just sitting around. When I have nothing to do, I start sewing. Even if there’s no one to buy.”

She sells most of her work on Facebook now, fetching between $250 and $800 for one of her creations. She also has mouths to feed: 12 children, 27 grandchildren and two great grandchildren.

No work, no money.

But it’s getting more difficult. In the past, most artists in Baker Lake sold their works through the town’s Jessie Oonark Centre, one of a handful of arts-and-crafts studios scattered throughout Nunavut. The studio offers workspace for jewelry-makers, print-makers, carvers and seamstresses.

For years, the centre has purchased and sold a bulk of the art produced in the town.

David Ford has operated the centre since 2008, after running his own gallery in Baker Lake, beginning in 1984. Ford says the amount of art purchased — and the number of artists — has declined considerably during the last two decades.

“The Inuit art market is not what it used to be,” Ford says. “A lot of the artists have died, a lot of galleries (in major cities such as Toronto and Vancouver) have closed. It’s been harder and harder to sell Inuit art.”

In the 1990s, for example, Ford would spend up to $300,000 a year on local art. Five years ago, that figure was between $100,000 and $120,000. Last year, Ford spent about $35,000.

Wall hangings that once sold for several thousand dollars now fetch a fraction of that, he says.

Remember Jessie Oonark’s youngest daughter, who along with her mother was rescued near starvation by RCMP in the winter of 1958? Her name is Nancy Aupaluqtuq, and she now has 11 children of her own.

Aupaluqtuq also became a distinguished artist and sculpturer, whose creations would retail for up to $10,000.

“I had galleries lined up to buy them,” Ford says. “(Now) almost all of those galleries are closed. I don’t have any place to market her work anymore. It’s still beautiful, but there’s no galleries calling.”

Such examples abound in Baker Lake. During one visit to the centre, a tiny, elderly woman walked in and spoke quietly with Ford. She left after a brief visit.

“She’s always looking for money every day, or fish,” he explains.

The woman’s name is Ruth Nuilaaik, 84, whose wall hangings have graced the National Art Gallery and the WAG. She is the daughter of the legendary Inuit artist Luke Anguhadluq and widow of Jessie Oonark’s son, Josiah Nuilaalik, a well-known sculptor.

In fact, it has long been a source of unfortunate irony to Ford that the Inuit artists who have produced works through the years that continue to sell for tens of thousands of dollars in auction spent the bulk of their initial profits at the Northern Store. And that was during the good times.

Their works hang in galleries alongside Van Goghs and Picassos, but most live in modest homes and still live largely off meals of caribou and fish, which they hunt and catch themselves.

“Every one of them is poor,” Ford says. “But you go into southern galleries and they’re like gods on the wall. They see their stuff in galleries for thousands of dollars and they got hundreds. They’re feeling they’re taken advantage of sometimes.

“It is sad. Sometimes people cry in front of me. I’m dealing with artists who are hungry and they need diapers for their grandchildren. It’s awful.”

However, others in the Inuit art industry bristle at any notion the art form is dying.

Debbie Jones, vice-president of art marketing for Arctic Co-operatives — the largest purchaser and wholesaler of Inuit art in the north — says Baker Lake is particularly affected by the loss of artists, not only to time but to the lure of jobs at a nearby gold mine that opened in the last decade.

“(Baker Lake) is one small community from a production perspective,” says Jones. “There are many communities that continue to produce at a very high level. It’s a sliver of what’s really happening in the market place.”

For example, Jones says there are communities such as Iqaluit and Pangnirtung where art production is increasing.

Arctic Co-operatives has 32 stores across the Nunavut, the Northwest Territories and the Yukon, where the art is purchased, then flown to the company’s wholesale outlet in Mississauga. The outlet still attracts buyers from around the globe: museums, collectors, galleries, gift shops. From where? Paris, London, the U.S., Switzerland.

“We’re holding our own, because there are new players coming into the market place,” Jones says, when asked about sales. “Where we’ve seen a drop off is those dedicated galleries that have closed in the last number of years.”

Jones acknowledges the co-op’s purchases have declined about 15 per cent in the last five years — not due to a lack of galleries or collectors — but to simple attrition of older artists.

Further, Jones adds, there’s a distinct difference between traditional art still being produced for collectors versus more marketable contemporary art forms, including fashion and jewelry.

“It’s important to note the industry has many different facets,” she says.

Still, in Baker Lake, it’s fair to begin questioning the future of an art industry that once provided the “bread and butter” for a community going on three generations.

Then you meet Mary Yuusapiq Singaqti, 80, who is moving gingerly. She seems frail at first before you find out she’s nursing two broken ribs from a recent ATV accident while out hunting with her husband Norman, who is in his 70s.

“We were up on the land,” she explains, in Inuktitut. “We’re going to go hunting until we can no longer walk. My husband says, ‘If I die out there, leave me out there. Bury me right there and then.’”

This is the same Mary Yuusapiq Singaqti, another daughter of Oonark, whose wall hangings will soon be featured in a WAG solo exhibition.

Is she looking forward to such a distinguished honour?

“I worry if people are going to like them,” she says. “We were brought up like that. We were always brought up to not thinking you’re too famous or too proud.”

Her answer echoes what Ford describes as a personality trait shared by many Inuit artists.

“They don’t recognize themselves as being famous,” he says. “Things are no different for them. Everybody still goes hunting and fishing. That’s their main source of food.

“People here are very modest. They don’t like to show that they’re proud. Most of them would say they’re not good artists… even though they’re amazing artists. They always think they could have done better.”

But then they’ve never had much. Rarely wanted more.

Over 50 years after surviving on the sinew of rotting caribou hooves, William Noah, 72, is perched on his favourite chair in a house in Baker Lake he built with his own two hands. Noah and his wife, Martha, have been married almost 55 years and raised six children.

Noah’s paintings depicting images of his youth in Back River have been shown in galleries in Toronto and Ottawa. But these days he has about 20 more paintings waiting unsold in a spare room and hasn’t had an exhibit in more than three years.

“Some days you get discouraged but you just keep on working,” he says.

Martha, 73, was raised about 100 kilometres north of where William did, but the two met only after their families were relocated to Baker Lake in the late 1950s. When they started dating, Martha says, the priests watched them like “guard dogs.”

Martha is an acclaimed jewelry-maker whose work has appeared in galleries from Vancouver to New Brunswick. And almost every day she walks a couple of kilometres to the Jessie Oonark Centre to work.

“I’m an old woman,” she says. “If I get tired, I go home.”

Martha’s specialty is earrings — “Whatever hangs, I make it” — and she works for some “bread-and-butter” money along with, she strongly believes, an extended lease on life.

“I like it,” she says. “It’s… myself. Coming from me.”

So by the time Martha is asked how long she will continue to trek on foot to make her earrings, the answer is obvious.

“As long as I walk or see.”

The Arctic is beautiful. It is open. It can hide pain beneath a serene exterior.

The Arctic demands that you survive.

For visitors such as Boris Kotelewetz, who never left, it explains why the inhabitants who settled an unforgiving land more than 1,000 years ago — who traded with Norsemen and European explorers and whalers — always had within them the modern art produced in the last 60 years.

They had made necklaces out of caribou teeth. Women in some tribes wore face tattoos and adorned their braids with sticks.

“The skill was always there,” Kotelewetz says. “It was an innate thing. If we didn’t have something of beauty, I don’t know what kind of life we would live, or even if we could survive. We need that, just as much as we need the wilderness.”

The art, he believes, is essential to see how the work reflects the environment, how an artist sees their world.

“How important is that, not just for art but for us as Canadians?” he asks, citing soapstone carvings as a prime example. “The first thing you notice is the pride oozing out of the rock. How do you capture that? How do you carve pride?”

David Ford, whose Inuit heritage dates back three generations reasons: “Look, it was a big change of life for them. They’re coming in off the land and now living in modern civilization. The church was quick at recruiting them and saving their souls. They were told their Shamanism was wrong and they had to be Christians if they wanted to go to heaven. It’s like they were shot from the Stone Age into modern civilization.”

Elders born in tents or igloos now watch satellite TV and check their iPhones for texts.

So how have Inuit people managed to survive, as best they can, in a world not of their own making? How to they tell their stories?

Noah Tiktak has one answer: Ask them.

“With all these modern technologies, if we want to learn something we just Google it or go on Facebook,” he says back in his shed in Rankin Inlet.

“Come north and learn from the heart, learn from the person. All too often, people who don’t know about us teach others about us. You want to learn about Inuit culture, go to the source.

“We’re here. We’ve always been here. Even before Christopher who? in 1492.”

Tiktak’s eyes are smiling again.

“Inuit humour,” he says.

And what would Tiktak tell those who asked?

“We’re very open,” he says. “We’re very strong. Our culture is very rich. Even in this year, 2016. We’re still doing something that our ancestors have been doing for thousands of years: sharing.

“You want to survive in this world? You have to share your catch, share your knowledge. That’s what we love to do, is share a part of who we are. Because when you look at the world, there aren’t very many Inuit. And we want to teach the world about ourselves, whether it’s through our art, our songs.

“That will to teach is still there. That will to learn is still there. It will never die. The government tried to kill us off. They tried to make sure we didn’t use our language in school.

“But no matter what they did to us, we never died. They did not break me.”

The Arctic is beautiful.

The Arctic demands that you survive.

randy.turner@freepress.mb.ca Twitter: @randyturner15

About this project

Ground will be broken on the WAG’s Inuit Art Centre in 2017. The ambitious project, which will feature the world’s largest collection of Inuit art forms, is scheduled to open in 2020. In anticipation, the Winnipeg Free Press wanted to investigate the impact the centre might have, not just on Winnipeg but on the Nunavut communities that have for generations filled the WAG vaults.

In Part I, the Free Press looked at the Inuit’s often painful history and how it is told through art. Part II focuses on the Inuit Art Centre’s mission, and how those behind the project believe it will redefine the role of galleries and museums.

Ground will be broken on the WAG’S Inuit Art Centre in the first part of 2017.

The ambitious $65-million project, which will feature the world’s largest collection of Inuit carvings, wall hangings and painting, among other art forms, is scheduled to open sometime in 2020.

In anticipation of the project, the Winnipeg Free Press wanted to investigate the impact the centre might have not just on Winnipeg, but the Nunavut communities that have for generations filled the WAG vaults. And just how both north and south will benefit from the bridge between cultures.

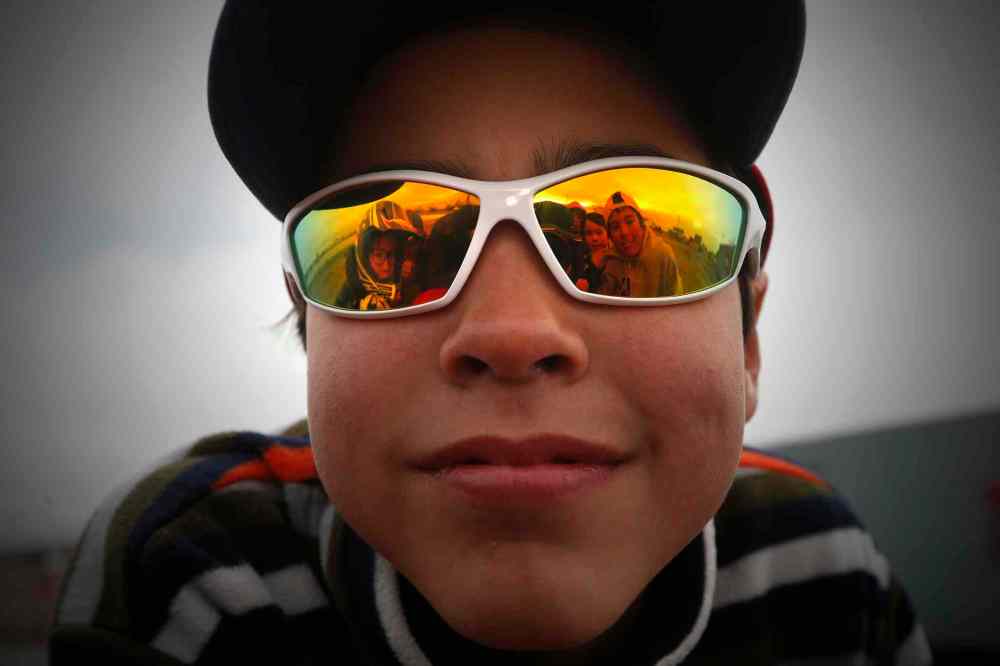

And we wanted to begin at the source. In late September, reporter Randy Turner and photographer John Woods travelled to the communities of Baker Lake and Rankin Inlet to interview and capture images of Inuit artists, young and old. They attended jigs, they ate boil caribou with an appetizer of cubes of beluga whale blubber.

But, mostly, they discovered firsthand what most Canadians don’t know: that the Inuit’s often painful period of colonization, which gave birth to the modern art form, has left lasting scars and a fierce will to persevere.

This is the first of a two-part project. Part 2, next Saturday, will focus on the IAC’s mission, and how those behind the project believe it will redefine the role of galleries and museums in the community.

Randy Turner

Reporter

Randy Turner spent much of his journalistic career on the road. A lot of roads. Dirt roads, snow-packed roads, U.S. interstates and foreign highways. In other words, he got a lot of kilometres on the odometer, if you know what we mean.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.