She shoots, they score Hutterite women find ways to respect culture, faith while playing hockey

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 09/03/2018 (2837 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

MACGREGOR, Man. — On the scoreboard, the seconds tick down: six, five, four. The ice around the goal is cluttered with defenders, but somehow the young woman spies a lane. She lines up the shot and snaps her stick forward.

The puck hits twine; it’s a goal. The buzzer sounds. The crowd bursts into a roar.

Yet as her teammates glide off the ice for intermission, they do not look euphoric. The first period was a grind; the second one, too. They clomp single file to the dim-lit dressing room, cheeks flushed from the effort, faces drawn in frustration.

Once inside, they sink onto benches with a tired sigh and pull off their helmets. Underneath, to keep the sweat from their eyes, some have tied their simple black kerchiefs — called tiechlen — around their braided hair, like a bandana.

Against one wall, Tirzah Maendel leans an elbow on her knee and adjusts the sky-blue cotton skirt that flows down to her ankles. She surveys the team with a wry smile and a glint in her eye; to those who know her, the look is familiar.

“Can I start swearing now, or what are we gonna do?” she says.

Outside this room, the utilitarian MacGregor rink is filled to the rafters with people. Every seat in the heated viewing gallery is taken, and fans cover the benches inside the arena. In the cold, their breath condenses into plumes of fog.

For years, this Louis Riel Day charity game has become a local tradition, a flash of excitement in the long grip of winter. There is no other event quite like it, in all of Manitoba — and maybe not even the world.

Welcome to the annual clash of the MacGregor Iron Maidens and an all-star squad of Hutterite women.

Their jerseys declare them the Baker Storm, but these 15 players come from Hutterite communities scattered across southern Manitoba: from Fairholme and Maple Grove, and from Keystone, Crystal Spring, Oak Bluff and Oak River.

The roster includes two of Tirzah’s sisters, Judith and Hannah, and a passel of her cousins. Among them, there are three Wurtz sisters: Doris, a teacher at the Baker school, as well as game rookies Tabitha and 17-year-old Anya.

(“This is not helping the stereotype that all Hutterites are related,” another relative groaned, earlier.)

And there is Tirzah’s sister-in-law Karissa Maendel, the de facto captain, who has the stance of a seasoned defender. The Maendel sisters sometimes joke that their brother Jonathan married smart; he married the best hockey player.

This is the only time each year they get to play all together, and they share one mission: to win.

But right now, they are losing. They are only down by one goal, thanks to that buzzer-beater in the second period, but the score is flattering. The Hutterite women have been scrambling: rushes fizzle out, forwards trail the defensive play.

Still, they go into the second intermission with the score locked at 4-3. Goalie Esther Waldner has kept the Hutterite women in it; by the end of the second, she’d faced nearly a third more shots than her team unleashed the other way.

So there is a path to victory, for the Hutterite women. They have 20 minutes to find it.

The dressing room erupts with lively discussion, mostly in the Hutterisch dialect of German, peppered with English. The women chatter about how to counter odd-man rushes, and the need to poke-check the MacGregor attackers.

“And for Pete’s sakes, skate,” one woman calls out.

Once, a man from Long Plain First Nation came to visit nearby Fairholme. He made a wry quip about the overall tone of Hutterite life: “they always yell,” he said, “but they never fight,” and now Tirzah, 37, reminds a reporter of that quote.

She raises her voice, to cut through the clamour. “We are playing completely by ourselves,” she laments.

The problem there, another player replies, is that they never get to practise together. Considering the lack of familiarity they’re still holding it together, and coach Chris Maendel — another of Tirzah’s cousins — agrees.

“We’re doing good, considering everything else,” he says.

To beat the Iron Maidens, they’ll need to do better. Karissa stands up to make an observation: the MacGregor goalie almost never goes down into butterfly, she notes, but the Hutterite squad has been shooting mostly at her shoulders.

Keep the shots low, Karissa explains. She demonstrates in the middle of the dressing room floor.

“We’re not shooting for the moon out there,” Tirzah declares, in agreement.

So there is a chance, and yet the task ahead of them seems daunting. Yes, the score is close; but the Iron Maidens, in their all-black hockey pants and jerseys, look so much sharper, more dangerous, more controlled.

But are they really? Or is it just that they’re what the world outside expects hockey players to look like?

It’s time to go. The Hutterite women grip their sticks and slip their helmets back on. For a moment they huddle together, eyes bright with determination. In the sallow light of the room, their skirts bloom a garden of colour.

They march out. Back to the cheers of a crowd that, Hutterite and outsiders alike, is very much on their side.

As they leave, Karissa delivers one last set of marching orders to her team.

“Play good, skate fast,” she calls out.

It’s just hockey. It doesn’t need to be complicated.

If you were to set out from Winnipeg searching for the heartbeats of Hutterite hockey, this is where to find one.

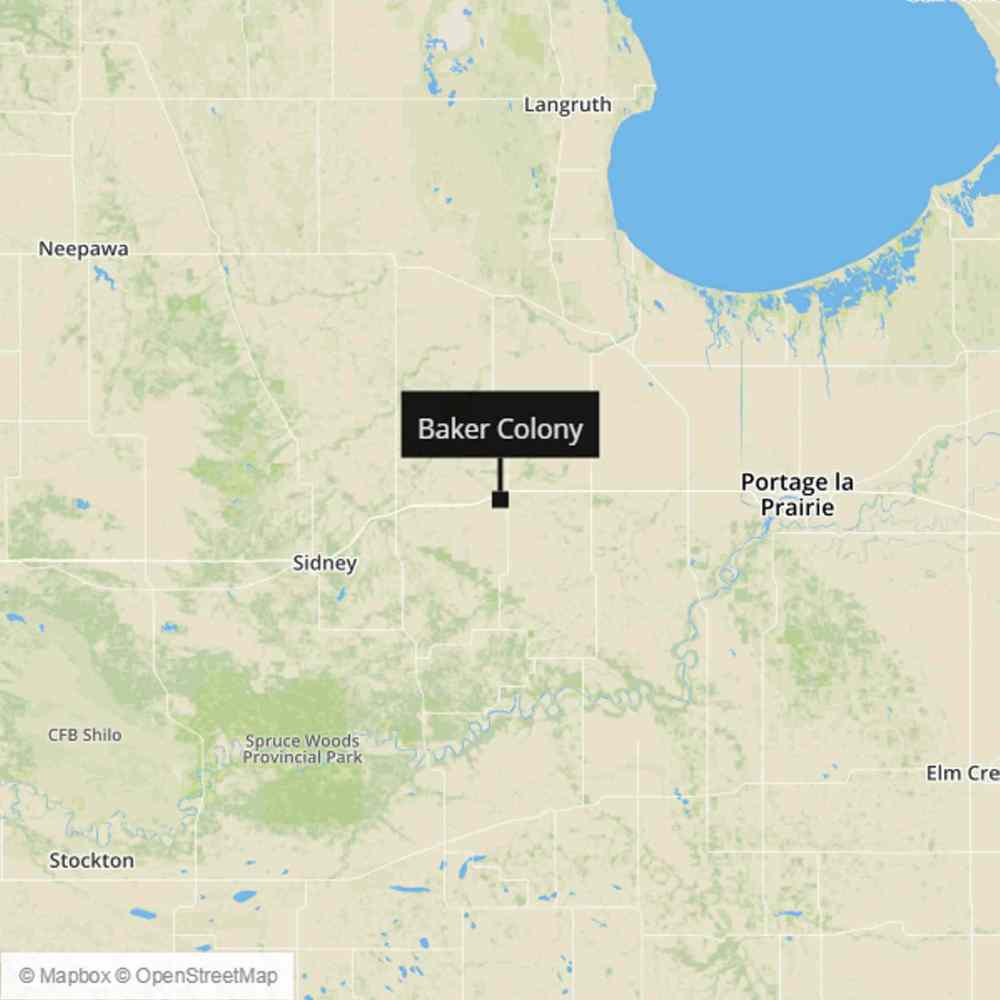

Turn south off the Trans-Canada Highway, about 24 kilometres west of Portage la Prairie. Keep straight until you meet a narrow gravel road. Follow it west, over the lip of the Manitoba Escarpment, past furrows and farms and hibernating fields of corn.

At the road’s end is a tidy cluster of buildings, bounded by spruce, and this is where Baker Colony grows.

About 110 people live here, most of them Maendels and Waldners, following the vision of a communal Christian life their ancestors set out nearly 500 years ago. Since 1973, that life has bloomed on these 4,500 acres of sandy soil.

The road makes a slow circle through Baker. It winds past the bustling Better Air manufacturing plant, where the colony makes barn ventilation fans and concrete accessories; past the two-family houses set in manicured rows.

At the heart of the settlement is the kitchen, where the community’s meals are prepared and served. Downstairs, a busy sewing room, where Baker women make blankets for charity missions, including an orphanage in Haiti.

On the southern edge of the community lies a school with gleaming-clean floors. About 30 K-12 students from Baker come here to learn; through televised links to other colonies, teachers provide distance education to many more.

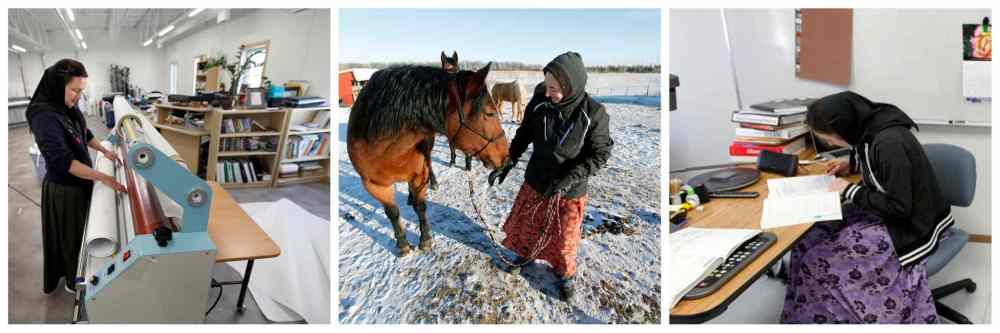

Next to the school is a hockey rink, a little narrower than regulation, dusted with snow. Beside the rink is a bookstore, stocked with Hutterite histories and German-language picture books; above that is a print shop, its window winking down at the ice below.

Here, among tall rolls of canvas, paper and the smell of warm ink, is where Tirzah Maendel spends most of her days, and some of her nights: folding and cutting cardstock from the printer, watching hockey on the print shop TV.

In a way, the annual MacGregor game is Tirzah’s project. She demurs from taking too much credit; it’s a community effort, she insists, and that is also true. But other players trace the Louis Riel Day game’s roots back to her efforts.

“Honestly, this whole thing started because of her passion,” her sister Judith says.

They were always an athletic family. In the 1960s their mother, Pauline Maendel, and aunt Rita Wurtz played on a landmark all-women’s baseball team in Fairholme; in 1979, Rita and another aunt ran in the first Manitoba Marathon.

“We blazed the trail for you,” Pauline tells her daughters one afternoon over coffee.

Among the Maendel kids, that sporty spirit blossomed. When the sisters were younger, Judith remembers, some colonies’ kids didn’t much like to visit Baker; her family had a way of pushing friendly volleyball games to the edge.

It wasn’t intentional, Judith explains. It’s just the way they loved to play.

Her cousin Doris Wurtz laughs, and shakes her head. “Tirzah convinced me once to play hockey here, with their guys,” Wurtz says. “I think I quit midway, and you couldn’t shoot me on that ice again… they were so intense.”

As the middle of the eight Maendel kids — two boys and six girls — Tirzah was a natural heir to that competitive tradition. From the time she could skate, she adored hockey; she was a “rink rat,” Doris says, always clamouring to play.

To her grandfather’s chagrin, Tirzah never had a knack for knitting: “We can’t all be seamstresses,” she says brightly, “and we can’t all be hockey players.” But her hands heard the language of sticks and pucks, and spoke it intuitively.

Baker didn’t have enough boys to field full teams, so the Maendel sisters were enlisted to round out the numbers. Judith, sometimes, resented the pressure — she prefers tennis — but Tirzah thrived every time she got on the ice.

She wasn’t the fastest player out there or the strongest. But she was tenacious: when she took bumps, she gave back as good as she got. She took pride in planting herself in front of the net, mucking in corners, digging for pucks.

“The competition was way more intense, but she loved that pressure, she loved that challenge,” Judith says. “She loved competing with the boys. And then even her mental toughness, made her capable of having that edge.”

The fact that hockey flourished on Baker, for girls and boys alike, was in itself a progression of Hutterite life.

That life can change very slowly until it changes fast. For instance, older men remember the days of their youth, when they tilled the fields with teams of horses; one year, their communities bought tractors and they never looked back.

Hockey, too, was a little like that. As a boy growing up on the Elm River community, about 50 kilometres east of Baker, Tirzah’s father, Jonathan Maendel, soaked up the legends of the old six-team NHL from a crackling radio.

Once, when he heard grown-ups talking about the Montreal Canadiens and Toronto Maple Leafs competing for the Stanley Cup, the youngster thought the game was to be held in Portage la Prairie. They were simpler days, then.

But there was no rink in Elm River, back then, and kids weren’t allowed skates. So they weren’t supposed to play hockey; adults thought that youthful afternoons would be better spent on chores or catching up on Bible study.

So the boys, undaunted, fashioned skates out of lumber and wire. After school, they’d slip down to the frozen river, where they’d cut sticks from tree boughs and knock around horse-manure pucks. They were disciplined if caught.

The very essence of sport

We live in a world saturated by sports. Through this wall-to-wall attention, simple games are transformed: becoming an entertainment behemoth that raises legends and arenas and, in the Olympics, the greatest spectacle on earth.

Underneath it all, a question we must sometimes pause to consider: what does sports really mean?

Until three months ago, I thought I had an inkling. Through a few dabbling years on the sports beat, and in the years since, I bore witness from the sidelines of glory. I covered Goldeyes playoffs and the last FIFA Women’s World Cup.

I was there in 2014, on the floor of the MTS Centre, when Jennifer Jones became an Olympian. And there a little more than a year later when she led her team to her fifth Canadian championship; and again last month, when she made it six.

And I have known high school and university players, as they strived for championships. Talked to David Onyemata, the first Manitoban drafted into the NFL, minutes after his first pre-season game as a New Orleans Saint.

I have spoken to Jets, in a dressing room thick with the tang of fresh sweat, and craned my neck to ask questions of NBA players. So I have seen how sports celebrates who we are, making myths of the best (and worst) of our nature.

But until this story, I don’t think I really saw the heart of what sports could be.

We live in a world saturated by sports. Through this wall-to-wall attention, simple games are transformed: becoming an entertainment behemoth that raises legends and arenas and, in the Olympics, the greatest spectacle on earth.

Underneath it all, a question we must sometimes pause to consider: what does sports really mean?

Until three months ago, I thought I had an inkling. Through a few dabbling years on the sports beat, and in the years since, I bore witness from the sidelines of glory. I covered Goldeyes playoffs and the last FIFA Women’s World Cup.

I was there in 2014, on the floor of the MTS Centre, when Jennifer Jones became an Olympian. And there a little more than a year later when she led her team to her fifth Canadian championship; and again last month, when she made it six.

And I have known high school and university players, as they strived for championships. Talked to David Onyemata, the first Manitoban drafted into the NFL, minutes after his first pre-season game as a New Orleans Saint.

I have spoken to Jets, in a dressing room thick with the tang of fresh sweat, and craned my neck to ask questions of NBA players. So I have seen how sports celebrates who we are, making myths of the best (and worst) of our nature.

But until this story, I don’t think I really saw the heart of what sports could be.

This is an intimate story, following a Hutterite women’s hockey team in the leadup to, and aftermath of, their annual charity game against the MacGregor Iron Maidens. It is about pioneers, and how sports finds its life in a culture.

And it is about the women I met, particularly the unflappable Tirzah Maendel, whose sheer passion for hockey animates the event. She is the lens through which a story is told; but it is bigger than her, and bigger than that.

This is also about how I rediscovered sports, in an outdoor rink on a Hutterite community near Portage la Prairie.

Over the last several months, and well over a dozen hours spent in vivacious conversation, I listened to Tirzah’s patient explanations about the roots of Hutterite women’s hockey, and how it carried them to this landmark game.

There are, properly speaking, no material stakes in this game. There are no scoresheets and no statistics; the players will earn no money and no fame. After the game, neither team could recall who’d scored each goal.

Yet so passionate was Tirzah about the sport that sometimes I had to step back and remind myself that we were discussing a rural exhibition game. She could just have easily been talking about a national championship run.

It was then I realized that when you strip it down, sports means nothing, if not people and community.

Over the years, I have met enough athletes for whom the world is not enough. And, like climbing the world’s highest mountains, there is something beautiful in striving to be the best in the world, simply because it’s there to be seized.

Yet the material glories of elite achievement also serve to unmoor sports from their anchors, lifting the most coveted rewards out of reach. Fame changes sports; so does money, and these can drive wedges between sports and love.

Because I have also known enough young athletes, burned out by the pressure pushed on them by coaches or parents. I have known disappointed minor-league pros, clinging to an identity that depended on their greatness.

Or, I remember the words of Olympic gymnastics star Aly Raisman, after the former USA Gymnastics team doctor was convicted of molesting young athletes in his care; she had sharp words for the organization that enabled him.

“Their biggest priority from the beginning, and still today, is their reputation, the medals they win and the money they make off of us,” she said, of USA Gymnastics. “I don’t think they really care.”

This is the level where sports, all too often, goes right off the rails.

But what I discovered, in the course of reporting this story, was an antidote to those pressures. It was a vision of what athletic achievement can mean when players alone create the context of their successes, rooted in their community.

It is not lost on me that this lesson is shaped by Hutterite values, and their connection to place.

Over the course of several daylong visits to the communities of Baker and nearby Fairholme, I was reminded of just how little most Manitobans know about Hutterite life. We know so little about their history, who they are, what they believe.

In some ways, that’s unavoidable. The majority of Winnipeggers — and that’s most Manitobans — have few opportunities for meaningful interactions with Hutterite people, and Hutterites aren’t looking to evangelize.

Yet we are connected, by geography and economy and shared shared points of culture. And through this game — which annually draws hundreds to the humble MacGregor rink and now raises thousands for charity — that glows.

What the Hutterite players created, in this event, calls us back to the true heart of sport. Love for a game, and for each other; a love where achievements are defined not as escape from, but as part of everyday community life.

After the Olympics, when a nation celebrated those who succeeded but also bemoaned those who fell short, perhaps it is even more timely to remember this kind of example.

The elite summits of sports are glittering, fantastical. They saturate our media with near-mythological stories of heroes and villains, triumphs and failures. It is not without reason; many of those stories are indeed beautiful.

Yet so is this: an outdoor rink in a quiet rural corner of Manitoba. A woman who cherished hockey so much that she helped build a new height for it in her part of the world; unfettered by outside pressures, existing only for love.

-Melissa Martin

That was more than a half-century ago. Elm River has its own rink now; so do Fairholme, Springhill, Green Acres, and others. Perspectives changed, over time, and in many places.

At Baker, hockey started from a seed and sprouted into tradition.

It was not the first Hutterite community to play hockey. Yet even just among the 107 colonies in Manitoba, divided between two groups of the comparatively liberal Schmeideleut branch, the sport’s presence is not universal.

Like many things, if you ask five different Hutterite communities about it, you may get five different answers.

The divergence falls along internal political lines, moderated by the issue of how to keep communities in balance between Hutterite culture and the world outside. Communal bonds depend on that, as does economic survival.

In Hutterite faith, the needs of the community come before those of the individual. So at the core of any colony’s endeavour, activity or investment, there is one overarching question: what is the value of this, for the whole?

To navigate that question, every colony goes through its own process of deciding what it will allow. A community’s management is elected for life, and over a long span of time, their decisions colour and shape local conventions.

“The culture within each community is a little bit like towns,” says Frances Maendel, Tirzah’s sister and a teacher at the Baker school. “It’s the people, it’s the leaders you elect in, it’s the environment.

“Even if the Church has a specific set of rules, they create their own as well. The freedom is there.”

And at Baker, the structure was already changing. In the 1980s, the community began to transition away from hog farming, focusing on its promising manufacturing business. It was one of the first colonies to make that investment.

But manufacturing work is different than farming: more static, less varied, more repetitive. Now, colony members worked regular 9-5 shifts at the plant keeping production humming; in the evenings, they craved active outlets.

Whatever the reason, the community embraced sports. When Tirzah was young there were road trips to Winnipeg, to revel in the excitement of Bombers and Jets games; when she was eight, all of the Baker kids got their own skates.

The community then refurbished an old hog barn, turning it into an indoor rink. Around 1996, they replaced it with the crisp, brightly-lit outdoor sheet that stands there today. It was an investment, one they believed would be worth it.

“Why are we so into sports here?” Frances says. “It’s because people have valued it, and promoted it and encouraged it and paid for it. And they’ve participated.”

And few on Baker valued hockey more than Tirzah. A lot of her identity crystalized around being a good hockey player; she nurtured it even knowing she would never play in a formal league, or on a full-time women’s team.

Success in the sport, she realized, would look different for her than an athlete on the outside.

Outside her community, so much is invested to raise up one athlete’s greatness. Families routinely go into debt and uproot their whole lives to support just one person’s dream; in Hutterite life, that would, quite simply, never happen.

There was a beauty in that, though. It meant that the shape of success was Tirzah’s to define. What was the pinnacle of achievement, for a Hutterite female athlete? The path ahead was fresh and uncharted; the horizon stretched wide.

In her mind, she turned over those familiar questions: what is the value in this? How is this useful?

Through hockey, Tirzah had found her answer, one that hummed in tune with her culture.

“Confidence, work ethic, perseverance, teamwork, integrity, bravery can all be worked over, tripped over and stumbled upon at the hockey rink,” she wrote in a heartfelt 2017 essay about life as a female Hutterite player.

But those words came later, in the long afternoon of her playing career. Long after she was a feisty teen, mucking about for pucks on the Baker rink. Gritting her teeth to keep pace with her brothers, stoking the fire inside.

Back then, she didn’t yet know where hockey would take her.

In December 2007, a young woman named Danelle Wurtz, from the Oak River community, fired off an email to a group of other Hutterite women across southern Manitoba. (Wurtz has since married; she is now a Wollman.)

“No more mittogsht’n holtn and chatting late on week nights,” she wrote. “It’s an athlete’s life for you girls for the next week.”

When asked to translate that Hutterisch word, Tirzah bursts into laughter. It means “afternoon naps,” she explains: the traditional break for Hutterite women in the hours after the morning’s work is over and before supper begins.

That email served as the official invitation to the second-ever all-Hutterite women’s hockey game.

The first edition, organized the previous March at Oak River, had been a smash hit with players. It took a group effort to arrange it, and the hockey was far from perfect. But they were thrilled just to play together; the mood was exuberant.

After that game, the women buzzed with elation. They noshed on pizza, eagerly dissecting the game’s misfires and successes. Within days, they were emailing each other angling for a rematch; now, they just had to make it happen.

That was easier said than done. The women all played on their own communities where, depending on demographics, they’d team up with women and children, or slip in to compete with the men’s teams.

But logistics made it difficult for them to face off at the same place, on the same day.

“It felt like you were moving mountains to get everybody there,” Tirzah says, looking back.

Still, over the next few years, they managed to make it an annual event. Emails flew back and forth, as players brainstormed locations to play, and who else to invite. There were inside jokes, even tongue-in-cheek posters.

After games, Tirzah and others wrote recaps, recounting the action with the zest of any sports reporter.

Soon, Tirzah started to wonder how they would stack up against teams from the outside.

The Hutterite men sometimes played against outsiders; there were occasional games against beer league teams from nearby towns. Tirzah has played in a couple of those matches: one in MacGregor, another in Notre Dame.

Now, in 2009, she wanted to try it with the women — and when opportunity knocked, she listened.

One day that year, Tirzah and Karissa were visiting MacGregor. They decided to swing by the arena, just to see what was happening. The Iron Maidens were there, hosting a tournament, and the two Baker players settled in to watch.

When it was over, Tirzah approached the Maidens: would they be up for a game against the Hutterite women?

At first, the MacGregor team was surprised — and interested. The team had existed since the late 1990s, playing recreational games mostly against squads from places like Pilot Mount or Brandon; but this was something new.

“(The first reaction) was ‘oh, they play hockey?’” MacGregor veteran Dayna Yurkiw remembers.

Soon, that initial curiosity gave way to caution. The Hutterite women, Tirzah had told them, didn’t play in full hockey equipment. Gear purchases had to be approved by colony management, and they weren’t decked out like the pros.

“When you play an opponent that doesn’t have all the equipment, it changes the game,” Yurkiw says.

But Tirzah was persistent. Over the months to come, she approached five different Iron Maidens players to promote the idea of a game. In January 2010, she sent a message to the team’s Facebook, looking to ease their concerns.

The Hutterite women could try to scrounge up some equipment, she wrote, but it would be difficult for them to get used to the “cumbersome” padding. Still, she assured the Maidens, her group knew what they were signing up for.

“I think we can take care of ourselves, given that this is the way we have played for years and years,” she wrote.

She closed the message with a sentence that left no doubt of their convictions.

“The bumps and nudges are to be expected and can be taken as given and vice-versa,” she wrote.

One month later, she got her answer. The Iron Maidens extended the formal invitation to come play in MacGregor.“They were really, really good. It was exciting even to lose to them.”–MacGregor Iron Maidens veteran Dayna Yurkiw

Tirzah, excited, began contacting other players. That spurred another flurry of emails, good-natured and a little nervous. One player thought the MacGregor team would win, “for sure.” They’d have big plays, she figured.

“How bad can it be, and so what if they do beat us?” Tirzah wrote. “I’m fairly confident we can at least hold our own.”

As the game day drew closer, the Iron Maidens were also wondering about their opponents. They knew the Hutterite women would be playing in their traditional dresses. They didn’t know if the skirts would billow, or slow them down.

“I assure you, it doesn’t,” Yurkiw says, deadpanning.

At that first warm-up, watching the Hutterite women fly over the ice, one thought flashed in Yurkiw’s mind: “wow.”

The puck dropped. One of the Hutterite players was wearing black magic mittens instead of typical hockey gloves; when a puck struck her hand, the Iron Maidens gasped in sympathy. They weren’t expecting what happened next.

“She didn’t skip a beat, she went on to score a goal pretty quickly,” Yurkiw says.

The goals kept coming. The Hutterite women didn’t just win that first game: they dominated, crushing the Iron Maidens 11-2.

At the time, the MacGregor team was among the best in their recreational league, and the blowout left them both stunned and delighted. In net, goalie Chelsea Guy thought the Hutterites had the fastest release she’d ever seen.

“They were really, really good,” Yurkiw says. “It was exciting even to lose to them.”

She got used to the feeling. The Hutterite women won the next year, too, and the year after that. In fact, they collected an unbroken streak of victories right up until February 2017, when the Iron Maidens at last scrapped out a 3-2 win.

Tirzah is frank about that record: “I think we’ve gotten a little worse,” she says, “and they’ve gotten a little better.”

As the years turned, any early concerns about the matchup faded away. The Hutterite women adopted helmets, and the MacGregor team grew accustomed to how pucks would sometimes dance through the folds of opponents’ skirts.

The skirts are still a striking sight, to outsiders. But if that’s all people see, they’re missing the story.

“It’s the grit of the Baker ladies,” Yurkiw says. “They don’t give up, and they don’t get off the ice.”

In February 2014, one of the Iron Maidens’ usual players took a video clip of the action, and posted it to Facebook. It showed the game at full-tilt: the Hutterite women battling to get out of their end, then rushing into the offensive zone.

“This was my Hockey Night in Canada,” the player wrote.

Over the next two years, the three-minute clip went modestly viral, racking up nearly 4,000 shares. The Hutterite players curiously tracked its spread, as it filtered through various people and groups around North America.

Most viewers were enthusiastic: “Awesome!” was a common response. Hockey players loved it; so did some conservative Mennonites, who applauded to see how the women honoured their culture by playing in skirts.

But other comments were more biting. Sometimes, the players wondered if viewers were laughing at them.

“There was a lot of joking about the skirts,” Judith says. “I guess we’re used to it.”

At the time, the game’s renown was growing. The first match drew a handful of fans, mostly friends and family. The 2011 edition doubled the attendance, attracting a crowd of curious onlookers almost entirely through word of mouth.

The momentum kept building. In 2016, the teams added a silver collection, to support a family of Syrian refugees. They invited a television news crew from the city to come do a story; once again, images of the game went viral.“It’s girls in skirts, and they’re actually half-decent at hockey. I think it’s surprising to people.”–Tirzah Maendel

When asked why she thinks the game generated so much buzz, Tirzah shrugs, as if it’s too obvious.

“It’s girls in skirts, and they’re actually half-decent at hockey,” she says. “I think it’s surprising to people.”

It’s a cold February afternoon, and the big game is just five days away. Tirzah has borrowed one of the Baker community’s vans, and struck out for the 30-minute drive to Fairholme to visit her aunts. As she chats, snow-laden fields slide by.

Truth be told, sometimes she’s bemused by how the skirts cause a spectacle.

For instance, they took a trip to Florida once, just the women. When they strolled on the beach in their dresses, people craned their necks to stare. But when they returned in swimwear to go snorkelling, nobody even looked.

“It felt like, wow, that drastic difference, to just magically becoming invisible,” Tirzah says.

That happens nearly everywhere they go. Tirzah has travelled widely in recent years; she recently returned from her third trip to Haiti, where the Baker colony does charity work; last year, she traced Hutterite people’s roots in Europe.

Sometimes, on those travels, people ask if she’s required to wear the dress.

“I find it a puzzling question,” she says. “It’s not something that crosses my mind. This is how I live, how I identify, how I’m comfortable. It almost feels like (with the dress), you’re a representative of where you’re from.”

That feeling finds its way into the hockey game, too. Once, one of the players wondered if she should try the game in hockey pants. Tirzah, surprised, encouraged her not to; if they are a team, she said, then they should look like one.

So the skirts are their uniforms, as much as any jersey. The drape of the cotton announces who they are.

And maybe that explains why Tirzah is so much more conscious of the win-loss record than Yurkiw. It’s not the Iron Maidens who are seen as delegates of their culture and faith; no wonder Tirzah wants her team to be great.

“Does that make up for it?” she muses, aloud. “If people say ‘oh wow, hockey in skirts,’ and the second reaction being, ‘they’re actually half-decent at doing it.’ Then we’ve almost one-upped the spectacle. I don’t know.

“Let’s say we did play in skirts, and we were absolutely horrible,” she continues. “Then it would be a mockery, and then we wouldn’t be doing this, if that’s the direction it took. Then we’d be clowns on the ice.”

In the backseat, her friend Helen Waldner pipes up. “Is it the skirts, or is it more the intrigue that we’re normal?”

Tirzah chews on this. “But what is the difference?” she replies. “What is the difference between our team and theirs?”

“Well, the fact we’re Hutterites,” Helen says. “They don’t know much about us, and that we have normal interests.”

“But look at our team, Helen,” Tirzah says. “It’s the same for them. We’re moms, we’re teachers, we’re nurses. We’re somewhat professionals. So we’re the same, but we’re still different.

“That one difference being, we are Hutterites. We do live in a community. I don’t know. Are there more differences?”

Maybe these are really the same question. Maybe the wider public’s fascination with hockey in skirts, and on the differences between those who play with and without them, are all leading back to the same, deeper discussion.

To the Hutterite women, the dresses are thoroughly normal. This is what they wear to work, to rest, to play. Maybe, they sometimes joke, they don’t know what they’re missing; but the skirts are like a “second skin,” Frances says.

But to outsiders raised on a constant diet of consumer fashion, the dresses’ very uniformity is all at once alien and deeply familiar. They issue a visual challenge, to a materialist culture’s obsessions with identity and expression.

In other words, it’s not the skirts. It’s how the sight of women backchecking in them shatters assumptions outsiders place on the fabric. Hutterite women live a life in the dress; it’s outsiders who conjure them into walls that divide us.

Still, there are some differences between one team and the other — and these, too, hold their lessons.

After one of the big matches, the Iron Maidens were eager to do it again; Yurkiw asked the Hutterite women if they’d want to play more often. The reply was polite, but quick: no, they said. The annual game would have to be enough.

In that moment, Yurkiw realized how much work it had taken the Hutterite team to make the event happen. It was easy to lose sight of that on the ice, when both teams were just skating, lost in the rush and the sheer joy of play.

They will always share that joy, but they do not share all of the same obligations. For the Hutterite women, whether they are perennial hockey stars or not, this is certain: the responsibilities to their community will always come first.

“We’ve all got our barriers, and that’s what makes this game so special,” Yurkiw says. “We all get to step outside of our lives for that hour. It matters to a lot more people than us, and we owe that opportunity to the Baker girls.”

“Ready or not,” Tirzah announces, and she shoves her hockey bag in the back of a black Mercedes Sprinter.

It’s two hours before puck drop. The Maendel house is a flurry of action; the players punctuate their conversations with anxious laughter. They hustle gear to the van in hockey bags, in reusable grocery sacks, in laundry containers.

Tonight, they do not take dinner in the communal kitchen, but load up plates with pre-game carbohydrates. There are toasted ham sandwiches and toriss totchella, a traditional pancake they douse with sweet Baker-made maple syrup.

Frances is not coming to the game: she gets too nervous watching, she says, and she paces. She follows the progress on Twitter instead; maybe, she jokes with rookie player Anya Wurtz, the teenager should do the same.

“As if they’d let me,” Anya says, with a knowing glance towards her cousin Tirzah.

Whether she likes it or not, Anya is one of the team’s hopes for the future of Hutterite women’s hockey. The first generation of players are now in their late 30s. Eventually, they’ll have to retire; some have done so already.

As the years turned, the faces on the roster changed. Some of the pioneers of those early all-women’s games stepped away from the sport: they got married, had children, turned their focuses to family and community work.

Even Judith needed some prodding to return this year. She has a busy slate, working weekly shifts at the Portage Hospital as a nurse, and is an active equestrian. Besides, unlike her sister, hockey was never her favourite sport.

“You have no idea how hard Tirzah worked to get me back on the ice,” she says, laughing.

So how exactly did Tirzah manage to convince her?

“Well, it’s Tirzah,” their cousin Doris says. “I think she could do anything, and we’d be there to help her.”

As Tirzah breezes into the kitchen, she announces there’s a small problem. On the radio, she said that last year’s game raised $1,200 for charity, but now she realizes she can’t remember the exact figure. Did she overstate?

Each Hutterite family, Tirzah explains, has a sort of tongue-in-cheek reputation. For Maendels, it’s that they have a tendency to be overly optimistic about their endeavours: “Our works can’t quite keep up with our talk,” she laughs.

The game inches closer. The women pick at their pancakes, full of jitters. This is the calm, before the Storm.

For a minute, the women flip through the old emails from their first all-Hutterite women’s games, laughing at their youthful exuberance and inside jokes. They had forgotten about so much of them, in the decade since it all started.

“What else has been forgotten, that hasn’t been dug up?” Doris says, wistfully.

“That’s the story of the Hutterite life, Doris,” Frances replies. “You know that, too.”

As skates hit the ice, cheers echo through the MacGregor arena, welcoming the teams back for the third period.

In the stands, a Hutterite man raises his phone, holding it steady to stream the action for Facebook viewers back home. On social media, Hutterites across Manitoba ask for updates: which team is winning? Who scored a goal?

The puck drops. The teams start wheeling. The Hutterite women start shooting, quick and low.

Hadassah Maendel is the first to score, notching a tally just 49 seconds into the period to tie the game 4-4. Minutes later, Judith strikes for the go-ahead goal; Tirzah builds the lead with her own marker, 90 seconds after her sister’s.

They are rolling, now. Their intermission pep talk seems to be working.

Yet as she gets off her shift, Tirzah is wary of the score. She watches the play on the ice, and it doesn’t feel quite right; to clinch the game, she thinks, her squad will need one more goal. And she can’t feel it waiting on her stick.

That hunch proves right. With just two minutes left in the third, the Iron Maidens tie it up at 6-6.

Overtime. Four-on-four. The MacGregor team comes out flying, pushing the play deep into the Hutterite women’s end. They battle back, but over the next two minutes the Iron Maidens regroup to pressure them again and again.

Suddenly, it’s over. The puck slips into the Baker net. For the second year in a row, MacGregor wins.

The crowd exhales, but applauds warmly. For a few minutes, players from both sides linger to take photos, then glide off the ice. Tirzah is one of the last to step off; she cradles her helmet in her arm, its facemask loaded with pucks.

Near the boards, a family friend offers condolences. “You worked hard for those goals,” the woman says.

Tirzah runs a hand over her head, and laughs. “Yeah,” she replies. “A little too hard.”

It’s over, now. The players trudge back to their dressing rooms; spectators zip up their parkas to ward off the cold. They trickle out of the arena, climbing into truck for the dark drive home, to their cities and colonies and towns.

A peaceful silence settles over the arena. The players left it all on the ice, and now the ice carries it all to rest.

An hour later, Tirzah texts a reporter with an update. The event raised $2,734 for the Portage Hospital Foundation, she says. That’s almost double what it raised the year before, and a sure sign that the game’s reputation is growing.

“So it’s not just my Maendel mouth,” she writes.

Time slips by quickly, in the frigid lashes of late winter. The hours shiver into days, and then into a week.

At Baker, at Fairholme, at all the places where Hutterite women’s hockey holds root, life returned to its pattern. The big game slid into memory, displaced by a familiar ancestral rhythm of faith and family and work.

There is always something to do. There are things to be printed, to be made, to be mended. Children to teach and communities to feed. Blankets to be sewn for the Mennonite Central Committee’s global charity missions.

And there are the times in-between, when the work pauses for the afternoon and families spill into their kitchens for the coffee break they call lunchn. Time to nibble on apple pies and cheeses, and chase fresh gossip with laughter.

Life is never contained by a sheet of ice. It spans out so much bigger.

Yet the night after the game, Tirzah couldn’t sleep. She lay awake, mind racing, breaking the game down to its component parts. Somewhere, she hoped to discover what her team could have done to change the result.

It was the structure, she finally decided, or the lack thereof.

Even on the bench, she thought, their team’s communication felt slapdash and sloppy. That’s not a new feature: the Hutterite women always started the games slow, even going back to those matches they won by wide margins.

They used to joke that they beat the Iron Maidens just by confusing them. Then, it was enough.

“It almost feels like, for all the games, as long as we were winning we were OK with it,” she says.

So maybe next year, she thinks, they could organize the lines by community, so that everyone was playing with linemates they skated with most often. She would do well if she was flanked by her sisters Judith and Hannah.

Then again, she sighs, that could create a competition within the team, too. You’d have to be careful of that.

Yet they could find more time to just play together, to practise rushes and drills. They are Hutterites, after all, and cooperation is at the core of their faith, their way of being. With a little time, they’d be able to knit the team closer.

“That might be my goal moving forward,” Tirzah says. “Hopefully that’ll help improve the teamwork.”

She started to let go of the score. She immersed herself in the print shop, and the days rolled on; but when she watched the Canadian women lose the Olympic gold medal to the Americans, she empathized all the more.

“It was heartbreak all over again,” she wrote in an email. “But… same as with our game, the better team did win.”

When the sting of disappointment pressed too hard, she looked at the photos they had snapped when the game was over. Everyone was smiling, she saw, even the rookie players who entered the game so wide-eyed and nervous.

After the Hutterite women scattered back home that night, one fan, who watched in the stands, sent Tirzah a text.

“I love days and moments when I feel proud to be Hutterite,” she wrote. “This evening was one of those times.”

So maybe that makes it all worth it, all the wins and the losses, and the balancing act it takes to create them. What these women have built, on that rink in MacGregor, connects them to each other, and also to something greater.“I love days and moments when I feel proud to be Hutterite. This evening was one of those times.”

Money for charity. Pride in a culture. A gentle rivalry that draws communities closer together, and gives them a spotlight all their own; if it weren’t for the holiday game, Yurkiw thinks, the Iron Maidens might have disbanded.

Life for them, too, has gotten busier over the last seven years. They’ve only played three games this season.

“We’re just grateful,” Yurkiw says. “Grateful to have that quality game with the Baker ladies, to have something that brings the community together. It’s a lot more than we ever expected for a rural women’s exhibition hockey game.”

Night slides its comfort over Baker. A jaunty tune rings over the public address system, signalling time for the children to gather for their communal supper. The adults will soon follow, and for a reporter and a photographer, it’s time to leave Baker to its rest.

Yet, as we turn to leave, one memory follows us down the highway, back to atomized urban life.

Flashback to the first time a Free Press crew visited Baker. It was a cold night in December, in the darkening hours after the community’s supper. The sky over the nearby hills deepened to an inky blue, splashed with pink and purple.

Everything was quiet, except for the clatter of sticks and the scrape of skate blades on ice.

Tirzah sat on the edge of the rink, watched the men play, and waited. She turned her head, and flashed that sly grin.

“It’s Hockey Night in Baker,” she said.

Then she hopped off the boards and flew into the fray. She settled a pass on her stick, kicked up her skates and hustled the puck over the blue line. Feet pumping forward, driving towards the net, long blue skirt flowing behind.

Play good, skate fast, Karissa said.

Lives find a rhythm, and some things do change. But the game is simple, and always the same.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, March 9, 2018 8:57 AM CST: Corrects reference to Danelle Wollman, corrects reference to Fairholme