Old ways, new world As Hutterites mark 100 years in Manitoba, some colonies are struggling with record defections as the powerful draw of modernity beckons young members

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 08/06/2018 (2744 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

JAMES VALLEY HUTTERITE COLONY — You wouldn’t expect revolutionaries to be dressed in polka-dot kerchiefs and ankle-length frocks, or sporting jaunty black fedoras with suspenders holding up black trousers.

But in the 1530s, the Hutterites, who make up the oldest commune still practising in the world today, and who celebrate their 100th anniversary in Canada this month, were revolutionary in their stance against church and state.

The Hutterites, along with other Anabaptists such as the Mennonites and Amish, posed a threat to the state because they believed in the commandment: Thou shalt not kill. They refused military duty. That included refusing to pay a war tax imposed on citizens whenever a country went to battle.

Just as troublesome was the Anabaptist rejection of infant baptism. They believed a person needed to be an adult before he or she could choose to be baptized and follow Jesus Christ.

We may wonder today why the state would turn so bloodthirsty over a seemingly innocuous issue such as adult baptism. The church and state weren’t separate back then, and infant baptism was how the state registered its citizens. If there was no infant baptism, there was no record of the individual and therefore no way to tax that person. Hutterites say the Anabaptists were the first to take a stand for the separation of church and state.

And they paid the supreme price.

Switzerland, for example, introduced the death penalty in 1726 for all Anabaptists, while Hutterites were commonly burned at the stake or died on the rack or in rat-infested dungeons in those earlier times in Europe. The Hutterite population reached levels of 30,000 to 40,000 in Europe but persecution reduced their numbers to less than 100 several times.

Jakob Hutter was just one example. He was a hat maker from Austria who emerged as a leader of the new Christian sect from whom it took its name. The Hutterites began in 1528 near Nikolsburg, Moravia (an area that covers part of the Czech Republic and Slovakia today) but the man from whom they derive their name became leader five years later. He lasted only a few years. He was arrested in 1535 and met with the same fate as Anabaptist leaders before and after him.

Tortured on the rack and whipped on several occasions, Hutter refused to give out the names of other Anabaptists or reveal their hiding places. That enraged King Ferdinand of Austria and he was determined to make a public spectacle of Hutter.

A special torture was arranged in which Hutter was tied up and held under freezing water, then ushered into a steaming hot room. Brandy was then poured into the wounds left by the whippings and the brandy lit on fire in a public courtyard.

What is pacifism?

One interpretation of pacifism by a Hutterite man is that you can defend yourself and others but you can’t kill. That doesn’t mean Hutterites just curl up in a ball and hope the trouble goes away.

One interpretation of pacifism by a Hutterite man is that you can defend yourself and others but you can’t kill.

That doesn’t mean Hutterites just curl up in a ball and hope the trouble goes away.

Many believe you do what you can to restrain your attacker, using all your wits and physical strength, but you can’t kill the person. If you die, that’s the way it goes. You may well have died if you had taken up arms, too.

According to Paul Doerksen, associate professor of theology and Anabaptist Studies at Canadian Mennonite University, pacifism isn’t “withdrawal from the world.”

“Rather, the Christian pacifist engages the world, seeking justice, order, mercy, peace and so on in ways that are not dependant on violence.”

Embracing the belief that violence ought to be used to bring about good is “to express commitments that deny the way of Jesus Christ,” he said.

Jacob Hutter explained this belief to the governor of Moravian in a letter dated from 1535:

“Here we lie upon the barren heath, as God wills, without harm to anyone. We do not wish, nor desire, to do harm or evil to any man, yea not to our worst enemies. And all our life and deeds, words and work, are open to all.

“Yea, before we would knowingly wrong a man to the value of a penny, we would rather lose a hundred pounds, and before we would strike our greatest enemy with the hand, to say nothing of a gun, sword, or halberd, as the world does, we would rather die and let our own lives be taken.

“We have no physical weapons, neither spear nor gun, as is obvious to all. Our teaching, speaking, life, and walk is that humans should live peaceably in the truth and justice of God as genuine followers of Christ.”

That was Feb. 25, 1536. The Catholic Church has asked forgiveness for its role in the persecution of Hutterites. Over their nearly 500-year existence many Hutterites either died or relinquished their religion under the threat of death.

By the time the Hutterites left Russia and immigrated to the United States in 1874, there were fewer than 2,000 remaining. They migrated en masse to South Dakota.

Forty-four years later, under attack in the U.S. for their refusal to fight in the First World War, large numbers of Hutterites migrated into Canada, specifically Manitoba and Alberta.

The Hutterites have been a communal people for nearly 500 years, yet we hardly know them. We know how they dress. We know they share property and live communally. But most of us don’t know much more than that.

They are endlessly fascinating to scholars and have been the subject of many studies. They garner international attention. Israel, which has it own communal population in the kibbutzim, has hosted delegations of Hutterites from Manitoba twice in recent years to gain information on how colonies operate. Today, a former Hutterite from just west of Winnipeg is a farm boss on an Israeli kibbutz.

Communal life is integral to Hutterites, not just a way of keeping out worldly influences, and it separates them from other Anabaptists, such as Mennonites.

“And all that believed were together, and had all things in common,” it says in Acts 2:44. It is their key religious tenet. The gifts of God, Hutterites believe, are meant to be shared with all people and not kept just for one’s own use. They believe living communally is God’s command and essential to salvation.

So, who are the Hutterites? It may look to an outsider as though little, if anything, has changed during their history.

The reality, however, is that in recent years, Hutterites have experienced an upheaval unlike any in peacetime.

According to the Inside the Ark: The Hutterites in Canada and the United States, by Yossi Katz, a professor at Israel’s Bar Ilan University and University of Winnipeg scholar John Lehr, the number of colony defectors was very low through early Hutterite history in North America. Fewer than 120 people left colonies between 1874 until 1950, one study suggests. But in the following five-year period, nearly 150 left, although most returned.

The number continued to rise. From 1983-93, 600 people left the colonies. The rate of defections reached a watershed moment in the early 2000s, when a study found defections exceeded the birthrate. While migration from Hutterite communities has slowed, it continues at a historically high rate.

Some return, but many do not, says Ian Kleinsasser, a teacher at Crystal Spring Hutterite Colony near Ste. Agathe who is regarded as an authority on Hutterite history.

The reasons for leaving vary. The lifestyle and career choices may be too limiting. There can be conflicts with the colony’s leadership, not so different from other workplace conflicts that result in an employee leaving to find another job.

Young people are most likely to test the outside world but, increasingly, entire families are heading for the exits.

What Hutterite defectors don’t do is reject religion. Inside the Ark says people most often leave to join evangelical Christian churches, attracted by their message of personal salvation rather than a communal life. The churches welcome Hutterites and help them get settled. There has even been some recruitment.

“People are influenced by religion outside our tradition that has de-emphasized the community aspect of Christianity. That is something happening that we struggle with,” Kleinsasser says.

It’s especially hard to keep the message of individualism out of communes in the digital age. Non-Hutterite churches also rely on community to an extent, and they too are struggling, says Kleinsasser. “Christianity seems to be in decline in North America because of rampant individualism, which is also manifesting itself in churches.”

Defections take a toll on colonies both emotionally and spiritually. Hutterites do not believe a person can attain salvation without communal life.

Policies on defectors vary from colony to colony. Some of the more conservative communities will take a hardline approach and shun runaways to set an example to others who may be thinking of leaving.

But others take a more charitable approach, recognizing defectors are the children of colony families. Some allow visits only on special occasions such as weddings and funerals. Others, however, impose fewer restriction, keeping the door open for a possible return.

“People leaving is a process being evaluated by colonies,” Kleinsasser says. “We say we believe in freedom of choice (adults choosing whether to be baptized) and then if we punish people by not allowing them to come back, then we actually don’t believe in freedom of choice. We’re punishing people for exercising freedom of choice.”

After all, it’s their skill managing change that has helped Hutterites endure for so long. Colonies have survived by bending but not breaking rules, Lehr and Katz say.

Inside the Ark and The History of the Hutterites, Revised Edition, by John Hofer of the James Valley Hutterite Colony, were invaluable resources for this article. Inside the Ark takes its title from the belief among Hutterites that their colony is an ark of righteousness adrift in a sea of secular sin, Lehr tells the Free Press.

Defections, in combination with a dramatic drop in Hutterite birthrates, have raised the anxiety level among colony leaders. It was not long ago that Hutterites built families of a dozen or more children, leading to new colony branches every decade or so when the population rose beyond 120, considered an optimum size to keep everyone occupied and discourage malingering. A sharp reduction in the birthrate means it can take 30 years for the creation of a new branch.

That is, however, another area of drastic change. As more colonies move into manufacturing, workforce requirements are leading to population increases; depending on individual economies, the traditional “optimum” size could grow to 300 or more residents, some speculate. The price of agricultural land is also making it too expensive to establish new branches.

The explanation for the lower birthrate is, simply, that Hutterite women have put their collective foot down and reduced family size in an effort to preserve their health. Birth control is officially forbidden without a legitimate medical reason and permission from the colony’s minister. The average family size today is four to six children.

The changing family size also reflects the changing norms of society in general.

“The more affluent society gets, the less children they have,” one Hutterite man says. “Families want time for other things.”

And Hutterite women are marrying at an average age of 24, about four years later than they did a generation ago.

● ● ●

When Hutterites first arrived in North America in 1874 and settled in the U.S., they were not alone.

Scholars have documented more than 100 different religious communes that once existed in the United States, some of which were instrumental in helping Hutterites get settled.

Hutterite leaders first travelled to North America in a delegation that included Mennonite leadership. Mennonites chose Manitoba, but the Hutterites preferred South Dakota. All the Hutterites in Europe migrated, although about half were non-communal, who were eventually absorbed into Mennonite congregations.

Two communes in particular — the Amana Colonies in Iowa, and the Harmony Society commune in Pennsylvania — helped early Hutterite settlers.

If Amana conjures up images of refrigerators and dishwashers, because that’s where the appliance brand originated. The seven Amana communes began in Germany. They drafted a constitution and chose the name Amana from the Song of Solomon and, in the spirit of communal living, shared their property. They existed for more than 200 years.

They became wealthy through craftmanship such as brewing and clock-making, as well as from agriculture. The Amana colonies abandoned communal practices in 1931 during the Depression, and it was then that the community began manufacturing freezers. The Amana Corp. still exists today. The seven colonies are now attractions.

“I toured it two years ago,” says Kleinsasser. “The corporation employs over 2,000 people (in the original Amana fridge factory). The town is built in German-style architecture, like Europe.”

The Amana colonies were very helpful, but Hutterites got even more assistance from the Harmony Society, a commune near Pittsburgh.

By then, the Harmony Society had become a celibate group, in the belief that Jesus Christ’s second coming would occur during their lifetime. The Harmony Society loaned substantial amounts of money to the Hutterites when they arrived to purchase large blocks of land.

Today, Hutterites number about 45,000 in North America.

Learning the Hutterite way begins at an early age. Infants as young as 18 months old are taught to put their hands together, as if in prayer, before meals. Starting in kindergarten, children learn the importance of sacrificing individual aspirations for the good of the commune.

While there are myriad similarities among all Hutterite communities, Manitoba colonies differ in many ways from those elsewhere. Manitoba has by far the most liberal colonies, called the Schmiedeleut (SHMEE-de-leut) — literally translated as blacksmith or smithy people.

An unfamiliar life

When you visit a colony, it’s like leaving your own world behind and entering a new one. There’s a tangible feeling of piety and safety, but also a playful spirit at work.

From business practices to clothing to seemingly archaic regulations, there are many unique aspects of Hutterite life.

When you visit a colony, it’s like leaving your own world behind and entering a new one. There’s a tangible feeling of piety and safety, but also a playful spirit at work.

From business practices to clothing to seemingly archaic regulations, there are many unique aspects of Hutterite life:

Business owners on the outside sometimes complain colonies have an unfair advantage when they enter manufacturing because they don’t issue paycheques.

True, but the colony cares for its members from cradle to grave, Johnny Hofer says. It pays for their accommodations and food and provides spending money. The colony can’t lay off members if there’s a business downturn. Most colony businesses aren’t likely to achieve economies of scale, because they’re limited by the size of their workforce, although some successful manufacturers have begun hiring non-colony employees.

Another issue is monetary compensation when a person leaves a colony. The people leaving have helped build the equity of the Hutterite colony, after all. But many colonies require its members, when they come of age, to sign a legal document saying they won’t sue the colony for money if they leave. Of course, people may argue they signed the documents under duress and had no choice.

Where members were evicted, courts have sided with the colonies so far. However, in one decision a judge said it didn’t seem right to evict someone without giving them something to live on. Colonies have taken that as a warning to assist departing members because the courts may side differently next time.

Clothing is another distinction, but those restrictions are starting to loosen.

One description of when Hutterites were still in Europe said one could identify Hutterites by watching them eat: if they said grace before and after their meal, they were Hutterites.

“So that tells you they weren’t dressed differently at one time,” said Kleinsasser. But at some point, “clothing became an identity tag.”

When we think of Hutterites in Manitoba we think of black. The reason black came to dominate Hutterite attire is that at one time black cloth was regarded as church cloth and was therefore tax deductible. “More people are starting to go back to different colours, different colour pants, including jeans,” Kleinsasser said.

As well, baseball caps are starting to replace men’s black fedoras. In Alberta, a wide-brimmed black hat is worn, like what Amish people wear, but Alberta colonies are more conservative.

The head covers women wear started as a cultural practice that took on a religious identity.

Hutterites have many regulations, and many are deemed archaic, such as the ban on bicycles.

This was proposed by colonies near cities or towns for fear members would ride off to town for a night. It was then adopted by all colonies. Many colonies like James Valley continue the bicycle ban while other colonies, particularly Group 1s, have repealed the rule.

Wearing suspenders instead of belts is another old rule. Belt buckles were becoming bigger and ostentatious so belts were banned on all colonies.

Most marriage partners are found outside the home colony.

There’s a large publication dubbed “the spy book” on colonies that traces ancestry back hundreds of years. It gets a lot of use as young people thumb through the book whenever potential romances surface.

The farther apart the couple is regarding family relationships, the better. Even though marriage between first cousins is legal in Canada, Hutterites forbid such unions due to fears of genetic defects. Some colonies are even forbidding marriage between second cousins, said Johnny Hofer.

“My dad married a second cousin, my grandfather married a second cousin, and his father married a second cousin,” he said. It was important to him to try to find a mate that wasn’t a second cousin, he said, and he happily succeeded.

Hutterites can be bracingly blunt, which you can either find rude or refreshing, depending on your take.

The most orthodox Hutterites are the Lehrerleut, or “teacher people,” and somewhere in between are the moderates, the Dariusleut — the name derived from a man named Darius. The latter two groups are found in Alberta and Saskatchewan; Alberta has the most colonies in North America. (South of the border, Schmiedeleut dominate in North and South Dakota and Minnesota, Lehrerleut and Dariusleut prevail in Montana and Washington state.)

The differences can be large. For example, the orthodox colonies don’t have fridges in their homes. Each family has a fridge, but they’re all located in a communal kitchen to help foster a sense of community. But Manitoba colonies allow fridges.

No Hutterite group allows stoves in homes because everyone eats communally. However, many Manitoba homes have microwaves.

The orthodox Lehrerleut stick strictly to agriculture and haven’t launched a manufacturing base as the Schmiedeleut in Manitoba have done, which necessitates greater contact with the outside world. The Lehrerleut also spurn higher education. Many colonies still view a Grade 8 education as sufficient.

Hutterites don’t own their homes or their contents; everything belongs to the colony and, therefore, to all colony members. For example, Hutterites don’t believe in knocking on doors. They just walk in. It’s communal property.

There was a great fracture in 1992 among Schmiedeleut Hutterites, when their bishop, Jacob Kleinsasser, tried to make the colonies more open. He was accused of violating the constitution by trying to force changes undemocratically. There were court cases. Family members took sides.

The Schmiedeleut split into two factions: the liberal Group 1 wing that followed Kleinsasser and a more conservative Group 2 element that elected a different leader. Manitoba’s 116 colonies are split almost down the middle; when Schmiedeleut colonies in the U.S. are included, about a third lean toward the more open, liberal movement.

After the split, “the liberal Hutterites became more liberal, and the conservative more conservative,” says James Valley teacher Johnny Hofer. “Before, the liberal pulled the conservative a bit, and the conservative pulled the liberal a bit. It was a nice balance.”

Churches have split throughout Protestant history over assertions of becoming too worldly, or too resistant to change; a segment of the congregation will leave and form a new church. For there to have been only one major split in the Hutterite church during its time North America suggests a relatively cohesive group.

Jacob Kleinsasser died last year at the age of 95. His successor, bishop Arnold Hofer of the Acadia colony near Carberry, has made conciliatory overtures to his conservative counterpart. But reconciliation would appear unlikely in the short term; Sommerfeld colony’s Mike Hofer, who leads the other group, is regarded by many as a conservative hardliner.

● ● ●

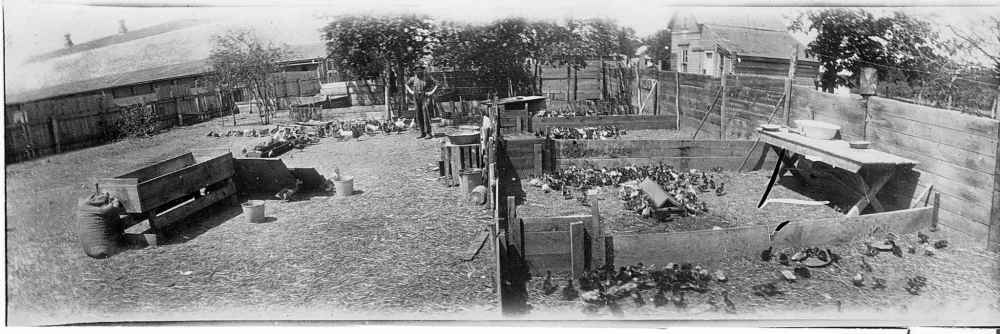

James Valley has four original buildings dating back to the birth of the colony south of Elie in 1918. They are believed to be the only structures still standing from the first settlements.

The plain, white buildings were constructed with the help of out-of-work carpenters during Winnipeg’s 1919 General Strike. Each houses four families.

“The buildings that we made ourselves later — we weren’t as good carpenters — are falling apart,” says Johnny Hofer, the German teacher at James Valley, and son of John Hofer, author of The History of Hutterites.

James Valley is one of the original five colonies in Manitoba, along with Milltown, Rosedale, Maxwell and Huron. All five settled in the RM of Cartier, just west of Winnipeg. Today, Cartier has 11 colonies, the highest concentration in Canada.

Before their arrival, the association for Manitoba municipalities sent out a circular warning that some people with a different culture and lifestyle would be arriving. By 1922, the RM of Cartier sent out a separate statement saying its experience with the newcomers had been nothing but positive. The document said Hutterites are hard-working, very moral and trustworthy, but they liked to stick to themselves.

Cartier may have been trying to mollify opposition, led by the Great War Veterans Association, which likened Hutterite pacifism to “complicity” with the enemy and a betrayal of Canadian values. It didn’t help the Hutterites were German-speaking. (Hutterites speak a German dialect from Austria commonly called Hutterisch.)

The GWVA went so far as to threaten to picket the border at Emerson and physically block the pacifists from entering. They called on their elected representatives to evict any Hutterites who entered and promised to work to oust politicians who supported their immigration.

The GWVA argued farmland should go to returning soldiers, not pacifist Hutterites. But it was really a non-issue as most returning soldiers weren’t interested in farming.

The Canadian government rushed through as many Hutterites as it could because it desperately wanted the Prairies settled with farmers. About two-thirds of the Hutterites from South Dakota made it across into Canada before the federal Privy Council gave in to public pressure and passed legislation restricting the flow.

The RM of Cartier is planning to commemorate the centennial of the five colonies, perhaps with a monument.

James Valley’s diversified agricultural operations include hogs, chickens and cows, as well as cereal crops and Old Mill Feeds. The colony also produces phone books for the 530 Hutterite communities in North America.

James Valley has not yet branched out into manufacturing as so many other Manitoba colonies have, making and marketing a host of products, including bike racks, picnic tables, fire pits, kitchen cabinets, fire engines, prefab homes, floor and roof trusses, meat smokers, wood-fired stoves, hog-processing equipment and graphic signage, among others.

Morning on a colony starts with a prayer thanking God for the day. There is a standardized part of the prayer, followed by a personalized part. Prayers are also said before and after each meal, once to say “please” and once to say “thank you.”

The church is a nondescript building that could, from the outside, be mistaken for a community centre or dance hall. It’s sparse and unadorned inside, but not gloomy. The walls are bare, without religious imagery or motifs, because Anabaptists believe nothing should distract from the word of God.

There are small, rectangular windows high up on the walls. The windows are there to let in light, not for congregants to look outside when they’re supposed to be listening to the minister. The glass is partly concealed behind wide, airy vertical blinds.

It has padded benches and is immaculately clean. That can sound redundant on a Hutterite colony as everything is spotless.

Members congregate in the evening for a half-hour service — 10 minutes for singing, 15 minutes for reading, and five minutes for prayer. The service is also broadcast into congregants’ homes.

Some colonies have scaled back evening services to only a couple times a week. Confession follows the Saturday evening service. Sunday — no holier than any other day of the week — is reserved for rest and spiritual refreshment.

The James Valley church has capacity for 225 people. The current population is 180, but it’s in the process of splitting. A branch is being built near Foxwarren in western Manitoba. There are 40 people at Foxwarren already but the entire branching process isn’t expected to be complete for another seven or eight years. The aim is to build a new colony and split equity from the old colony, so relocated members have the same standard of living they had before.

Of course, whether to adopt new technology and how to adapt to it is always a challenge for colonies, and the computer poses one of the greatest dilemmas they’ve faced. James Valley is no different.

The more orthodox communities in Alberta and Saskatchewan have imposed blanket internet bans, but many observers believe they’re fighting a losing battle; residents are getting their hands on smartphones one way or another. Blocking access to the outside world may keep some from defecting. Others may be motivated to leave because of the isolation.

On James Valley, a Group 2 Schmiedeleut colony, there are about 30 computers in the school and on business worksites. There is a single, overwhelmed public-access computer at the phone book production facility.

Computers aren’t allowed in homes. The concern, says James Valley colony manager Edward Hofer, is the effect on home life. Edward has a cellphone but he can only take phone calls or text with it. The colony is currently experimenting with a filter that would allow members to use smartphones, he says.

It’s vastly different at some Group 1 colonies. The most liberal, Crystal Spring near Ste. Agathe, permits home computers and many people have smartphones.

“As a previous elder said, the era of isolation is over. We cannot keep this out,” says Ian Kleinsasser, the Crystal Springs teacher.

Linda Maendel of Elm River Colony near Portage la Prairie even runs an online blog. Maendel is also author of the book Hutterite Diaries.

Technology has always been a challenge for religious communes, says Tony Waldner, of the Forest River Colony near Fordville, N.D. (although it’s located south of the border, it is a branch of a Manitoba colony). A century ago, Hutterite colonies nearly sided with the decision by Amish people to stick to the horse and buggy, he says.

“There was an issue about accepting the automobile and the Amish were against it and we were very close to making the same decision,” he says. “But we decided to go with technology. We decided first to go with the telephone, and then the automobile. Now we’re with the computer age.”

Those decisions are usually driven by business concerns.

“We don’t stay behind in any technology when it comes to farming and livestock operations. For that reason, we need the internet,” he says.

Then the rest of the colony typically demands equal rights. They’ll want to know why some people have access while others don’t. It’s a commune, after all, and property is supposed to be shared.

The problem is that the internet is far less regulated than television, which is banned on all colonies, as is radio. “We are at a crossroads right now,” Waldner says.

Crystal Spring leaders feel the church needs to help colony members make proper choices on the internet.

“We need to teach people what is appropriate and what isn’t and let them make decisions,” Kleinsasser says. “We feel that with an open and honest communal discernment process, and with an openness to God’s guidance, our communities will find a way.”

Orthodox colonies see the Group 1 Schmiedeleut as “a cautionary tale” — a people who have lost their way, some said. Conservative groups believe the openness at Crystal Spring will surely result in more defections.

Yet orthodox colonies in Alberta are experiencing the greatest exodus. Young men are leaving in droves to work in the oil patch. There are entire crews of riggers and drillers comprised of former Hutterites; they are popular with many employers because they have a reputation as good workers and are mechanically adept.

As a consequence, the ratio of women to men on some Alberta colonies is said to have reached crisis proportions. Lehrerleut women have had to take on traditionally male jobs. The shortage is so great the prohibition against mating with wayward Schmiedeleut colonies has been lifted, in some cases.

No one can say how much the exodus in Alberta colonies can be blamed on the digital world. The money that can be earned in the oil patch is certainly a factor. But there is always the fear that too many restrictions will only lead to more defections, according to Inside the Ark.

After the church, the community kitchen is the second centre of a colony, and that’s the case at James Valley. The entire community congregates there three times a day for meals and for special occasions such as weddings and funerals.

It’s run by two women, usually an older one and a protege. It’s a tough job and a huge responsibility. The women work from ages 17 to 45, then take early retirement. It’s more like semi-retirement because people always have jobs to do on a colony. The age 45 cutoff is a throwback to a century ago when women still had family sizes in the double digits and shorter lifespans.

In addition, two women work as kitchen assistants, rotating through the helper positions in two-week stints. That is followed by another two-week stint in the bake house down the hall.

Lunch one day is potato soup so delicious that seconds and, if no one notices, thirds aren’t out of the question, along with deep-fried balls of sweet dough —”our Timbits” — and beets, sauerkraut and fantastic boiled chicken. As in church, women are on one side of the room and men on the other.

Laundry is the responsibility of colony women. Washing machines are forbidden inside homes; each family gets two time slots per week at the communal laundromat. The times change on a rotating basis so no one is unfairly advantaged or disadvantaged.

All of the women are seamstresses and make almost all the clothes on the colony, save for a few items such as men’s hats. Johnny Hofer notes the socks he’s wearing were made on the colony.

Thelma Hofer is the colony’s “material buyer.” She travels at least once a month to Winnipeg to buy fabric. As is the norm with nearly everything purchased for a colony, she buys in bulk.

And she emphasizes that she doesn’t have to get approval for the colours she buys. There’s a veritable rainbow of materials in the storage room and not much black that Hutterites are often associated with.

About 75 per cent of marriages are between people from different colonies. Thelma, for example, is from the Souris River Colony. Wives move to their husbands’ communities, taking them away from family and longtime friends, but that’s just the way it is in the life she has accepted, she says, adding she has five sisters and three are in different colonies.

Her husband has two sisters at different colonies.

Hutterites travel a lot to visit family and friends spread all over the place.

The men wouldn’t be able to handle the change of moving to a different colony, one woman jokingly says. “We don’t choose our colony, ” she says. “We choose our guy.”

That provides an explanation, at least in part, for why most surnames on a colony are the same. The men stay put and wives take their husbands’ names. That, along with the inescapable fact that few families immigrated here in the first place.

Women don’t have a vote on colony affairs. Even the female position of head cook is voted on by men. A group of James Valley women collectively shrug and say they tell their husbands how to vote. When one Manitoba colony couldn’t decide on whether to become Group 1 or Group 2 Schmiedeleut, the women essentially went on strike, refusing to cook until the men made up their minds.

“Hutterite colonies have the most democratic systems you can conceive of except women don’t get to vote,” says Inside the Ark co-author Lehr. Women are able to cast ballots in municipal, provincial and federal elections.

Expressing opinions that would raise eyebrows outside the colony, Thelma says she likes the traditional male-female roles and doesn’t think a woman would make a very good leader of a colony; women are too easily swayed and don’t command authority the way a man does.

And she is emphatic in her belief that a woman should not run a country. Nellie McClung would surely put her head in her hands and start to weep.

But Thelma — young, intelligent and serious-minded; someone who would likely succeed on or off the colony — has no frame of reference, never having seen a woman in a leadership role.

Author Linda Maendel agrees that feminism hasn’t arrived yet at Hutterite colonies. At the same time, she says it’s not a big deal. She isn’t aware of any groundswell of discontent.

However, Maendel, an educational assistant at a colony school, takes issue with Thelma’s belief that women wouldn’t succeed in leadership roles.

And when it comes to women not having a vote on the colony?

“I don’t think I even have an answer that would satisfy you,” she says. “It’s just something that’s always been. It doesn’t bother me.”

Several women at James Valley bristle at the perception they simply obey their husbands.

And things are changing. Maendel’s cousin is one of a handful of trained nurses from Hutterite communities; she now works in Portage la Prairie. About 70 out of more than 80 university-trained Hutterite teachers are female. Some women at the Springfield Hutterite Colony work in traditional men’s jobs as carpenters.

However, colonies are like time capsules from a century ago.

Hutterite women insist the full dresses they wear are very comfortable and they wouldn’t want to wear some of the immodest shrink wrap that passes for clothing on the outside. The clothes are also homemade and better quality than most store-bought clothing, they say.

Colony rules vary, but women generally wear one-piece bathing suits with a T-shirt over top.

Thelma has a special-needs son and she is fiercely devoted to him. She feels that she can trust community members not to take advantage of him, something she doesn’t believe would be the case off the colony.

Simpy put, she likes her life.

“I have friends I visit in Winnipeg and I would not trade places with them,” she says.

As a parent, who wouldn’t want a lifestyle where you are constantly crossing paths with your children every day? “That’s one of our sons,” Johnny Hofer says several times throughout the day.

“You simply can’t find a better life,” he says. “That’s just the way it is. And no one is selfish. It’s security from cradle to grave. But we’re all human. All the pressures you face in the outside world we have internally.”

● ● ●

As for marking their 100th anniversary in Canada, Hutterites are still working towards coming up with more concrete plans but colony members are grumbling about the lack of movement.

Colony leaders are now saying that since Hutterite colonies came to Canada over a period from 1918-1920, any commemoration will likely take place over the next couple years.

Some projects are underway. For example, Johnny Hofer is writing the history of the James Valley colony. James Valley is considering inviting its branches — it has branched off four colonies in 100 years and is in the process of branching off a fifth near Foxwarren — to the colony for a ceremony.

There are also plans underway to establish a Hutterite Centennial committee whose task it would be to organize events and publications aimed at commemorating this milestone. Work is underway at creating a Hutterite archive which, among other functions, will gather photos of early Hutterites for publications and presentation purposes.

Even though early Hutterites did not own cameras, they allowed neighbours and friends to take portraits or pictures of special occasions. Hutterite scholars are in the process of tracking down and digitizing these images.

So where do Hutterites go from here? How do they continue to survive in the digital age and beyond?

One troubling aspect to some Hutterite members is how little influence they’ve had on the rest of society. Throughout their history they had missionaries but the mission work disappeared in North America.

Johnny Hofer, when asked if he feels proud to be a Hutterite and part of the longest-living communal group in the world, answers with a yes and no. Yes, proud of what his forefathers and foremothers accomplished. But he wonders why Hutterite colonies haven’t done more to spread the message of Christianity with their special emphasis on non-violence.

Problems of persecution

Hutterites have been running for their lives for much of their almost 500-year history despite promises of peace and prosperity made across Europe and, in the late 19th century, in the United States. Pacifist beliefs and religious freedom continued to wear out welcomes from host countries, fuelling the itinerant existence.

Hutterites have been running for their lives for much of their almost 500-year history despite promises of peace and prosperity made across Europe and, in the late 19th century, in the United States. Pacifist beliefs and religious freedom continued to wear out welcomes from host countries, fuelling the itinerant existence.

•••

Dark clouds gathered over American Hutterite colonies when the U.S. became involved in the First World War in 1917 and began conscription of men between the ages of 21 and 31.

Hutterites had asked for military exemption before they immigrated in 1874 but then-president Ulysses S. Grant said he couldn’t grant it. He assured them, however, that the United States wouldn’t be at war for at least 50 years.

Grant was out by about a decade, and it was disastrous for Hutterites.

“They were pressured to buy war bonds and have their young men conscripted and they refused to do either,” said Inside the Ark co-author John Lehr.

Mobs formed and raided colonies, taking livestock and auctioning it off at rock-bottom prices. Young men were seized and beaten, others imprisoned.

The barbaric treatment of four young South Dakota men — brothers David, Joseph and Michael Hofer and Joseph’s brother-in-law Jacob Wipf — is an oft-cited illustration. They were sentenced to 37 years in prison and shipped to Alcatraz for refusing military duty.

They were handcuffed by day and chained to each other at night. They slept on a wet concrete floor. Still, they refused to put on military uniforms. As punishment, they were tied to the ceiling and beaten with clubs.

They were later transferred to a prison in Leavenworth, Kan. David and Jacob were placed in solitary confinement, while Michael and Joseph were hospitalized due to maltreatment but later died. As the supreme insult in death, they were dressed in the military uniforms they refused to wear while alive.

Hutterites started selling their land for as little as half the value and fled to Canada where the government wanted to settle the Prairies. The Hutterites had a standing offer from 1899 from the Canadian government promising military exemption and religious freedom.

Oddly enough, the government in South Dakota started inviting the colonies to come back in the 1930s. Money was scarce during the Great Depression and the colony land bases were too large for individual landowners to purchase. Many colonies did move back into vacant colony lands left behind. An estimated 80 per cent of colony land parcels were bought back by Hutterites.

•••

Hutterites immigrated to Russia in the 1770s. Catherine the Great, the Empress of Russia at the time, was of German descent and needed to fill land acquired in war that is now known as Ukraine. So she invited German-speaking people to settle the area.

Mennonites are remembered fondly for helping out the Hutterite people in Russia, said Tony Waldner of Forest River Colony in North Dakota. The Hutterites didn’t have enough property to make a living. So the Mennonites welcomed them to a place called Molochna, loaned them money and helped them build a village.

Catherine the Great had gave the Hutterites a 100-year contract, from 1770-1870, guaranteeing freedom of religion, military exemption and autonomy from Russian society. There was no need for them to learn the Russian language.

Those privileges started to break down at the end of the contract, with military exemption proving the most troublesome. They were given 10 years to relocate and that’s how they arrived in South Dakota.

•••

Before moving to Russia, Hutterites were in Transylvania, a region now in central Romania, and before that they were in Hungary. Before that was the Thirty Year War between Catholics and Protestants in Central Europe from 1618-48.

In the first months, 12 colonies were destroyed and another 17 were plundered. In one attack of an unarmed colony, 56 people were killed and 60 wounded. In total, more than 150 colonies were destroyed, and not just because of their Anabaptist faith; Hutterites had become quite prosperous, generating hard feelings from less-successful citizens. Their possessions were seized and they were expelled from what was then called Moravia, the lone European country that tolerated religious freedom.

Before that was the Turkish War, lasting 13 years. Hutterite colonies were raided and members killed. Survivors hid in caves and dug underground tunnels.

•••

The Hutterite movement began in 1528 in Nikolsburg in Moravia, which is an area that covers part of the Czech Republic and Slovakia today. Namesake Jakob Hutter was not alone in suffering torture and eventual execution; some 2,200 followers were slain during the mid-1500s.

An estimated 80 per cent of Hutterite missionaries were killed. One, Hans Purchner, was tortured and beheaded. Another, Jans Mandl, was imprisoned four times and finally executed. He was bound to a ladder and burned alive.

Ian Kleinsasser of Crystal Spring thinks the same way.

“Hutterites are huddling inward to protect themselves. Then everything outside the community is seen as sinful. Whereas the old teaching never really stated it like that. Some teachings say we can have the world in our communities. Not everything in the world is sinful.”

After all, Hutterite people benefit from health care, public education, and various government programs. “All these things are good,” says Kleinsasser. “We shouldn’t be judgmental. Look at all the ways we benefit.”

Many Hutterite colonies are challenging the insular thinking. For example, Group 1 colonies started sending young people to Brandon University in 1995 to become teachers. Today, there are more than 80 Hutterites teaching the English public school curriculum in colony schools.

As well, several women have graduated from the BU’s nursing program and are practising outside their colonies. However, working off colony is a line most colonies don’t want to cross.

Group 1 colonies firmly believe in education. Other colonies worry that if members get an education they’ll leave. Kleinsasser says that’s not ethical. “If not educating them is for the sole purpose of keeping them on the colony, that’s wrong,” he says.

“People say educate (our children) and they’ll leave. That is one of the things we’ve challenged and we say, ‘No, that’s not true.’ People have always left our community.”

In fact, that is exactly why commune members should have an education, he says. “I want to ensure that my children, should they decide they do not want to live on a Hutterite colony, have an equal chance to secure a livelihood outside the community and that they don’t end up being a burden on society. We are obligated to ensure they have as good as, if not better, education as people around us.”

Still, communal life is paramount and that must continue.

“It raises the question, as we become more involved in social issues around our communities, how do we maintain our identity as a people?” Kleinsasser asks. “At the same time, we have to open up if we are to become relevant.”

Expect to see Hutterites more engaged with the world around them in the future.

For example, Green Acres Colony near Wawanesa has sent young men for paramedic training and runs an ambulance service from its colony for that part of southwestern Manitoba. The Hutterian Emergency Aquatic Response Team recently assisted in a search and recovery of a Winnipeg man drowned in the Red River.

Crystal Spring members are part of the St. Pierre Voluntary Fire Service. Crystal Spring youth recently performed the play, The Robe, a story about a soldier who wins the raiment Jesus wore during his crucifixion in a dice game, in a Steinbach theatre. James Valley stocks Winnipeg Harvest shelves with vegetables. One Hutterite minister sits on the board of Siloam Mission in Winnipeg. Many colonies support Siloam Mission with food and donations.

“We have benefited all these years from living in Manitoba and it’s time to give back,” Kleinsasser says. “That is the direction we want to be moving.”

bill.redekop@freepress.mb.ca