Confronting COVID-19 on Manitoba First Nations: same enemy, different results Cramped, substandard living conditions and existing health issues elevate the danger in many Indigenous communities

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/01/2021 (1867 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Sioux Valley Dakota Nation borders the heavily travelled Trans-Canada Highway in western Manitoba, yet the community held back waves of COVID-19 cases that swept the area last year.

In the opposite corner of the province, Shamattawa First Nation, a remote fly-in community in northeastern Manitoba, had an outbreak so severe that the Canadian military was flown in to help after one-third of the 1,500 residents were infected.

How the two communities, situated 900 kilometres apart, have been impacted by the pandemic speaks to the complexity of COVID-19, and the dramatic variabilities among the 63 reserves in Manitoba.

Yet all these First Nations have a shared history of foreign diseases threatening their communities — and of maddening, systemic failures that persist today.

Cramped, inadequate housing combined with substandard health services, patchy, unreliable internet and a lack of clean running water add challenges that few non-Indigenous Manitobans face.

The Free Press spoke with leaders from different tribal groups this week about how emergency planning and traditional teachings have helped some keep the coronavirus at bay, while others struggle to contain COVID-19.

● ● ●

Almost a year into the pandemic, the 2,350 residents of Tataskwayak Cree Nation felt they had things under control.

Sacrificing social gatherings and raising the alarm about a nearby work camp had kept COVID-19 cases low in the community, also known as Split Lake.

That was until a Jan. 8 funeral at the local church. Everyone wore masks, people tried to keep their distance and many, including Chief Doreen Spence, visited only briefly to pay her respects.

But 170 people attended and someone had COVID-19 symptoms three days later. The community went into lockdown.

“We let our guard down, and this is what happened,” Spence says.

Nurses worked tirelessly to reach everyone who attended the funeral, ultimately finding 191 contacts, Spence says. Among those, the band sent people with the highest risk of dying from COVID-19 to an isolation site outside the community.

Ultimately, 27 confirmed cases emerged and, as of Wednesday, only seven cases remain active, suggesting compliance with the lockdown and honest reporting of contacts.

“I think everybody took this situation seriously and co-operated,” Spence says.

At the time, provincial public-health rules allowed only five people to attend a funeral, a number that has since risen to 10.

Across Manitoba, funerals have been a driving vector for cases on reserves, according to Dr. Marcia Anderson, a Cree-Anishinaabe medical officer.

“We do still see a pattern of clusters or outbreaks following gatherings, especially funerals that are well over the public-health orders,” she told a Jan. 22 Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs video conference.

“The high number of contacts really, really do overwhelm the local health resources,” she said, adding the AMC at that point had support teams deployed to five different communities at the same time.

“It would be very, very hard for us to send a team to a different community if that type of situation arose again.”

Spence says communities that have sacrificed so much over the past year find it very difficult to not have a proper goodbye for a loved one.

“It’s a hard balance,” she says.

And while Winnipeggers have held ceremonies to honour people using online platforms, that’s often not possible on First Nations with patchy internet service.

The community was up front with federal officials about what happened, and quickly got testing underway.

“We dealt with it and we’re moving forward,” Spence says. “I think it opened our community’s eyes, to what can happen again with another funeral.”

Spence hopes other communities can learn from the example, and that it doesn’t obscure the work done by her community to control the spread.

They use a facility in Thompson to quarantine people visiting Winnipeg, including for dialysis. That lowers the risk of an asymptomatic patient introducing COVID-19 into a crowded home, which has been linked to outbreaks in numerous Manitoba communities.

They also have a delivery system for food where couriers drop items at the border of the community, and residents deliver them to the local store.

Spence was at the forefront of a road blockade at the Keeyask megaproject last May, when four bands felt Manitoba Hydro’s pandemic protocols were putting them at risk. (They reached an agreement after Hydro secured a court injunction to have police clear the blockades.)

Tataskewayak has been proactive on the radio and Facebook, providing updates on COVID-19 protocols and the vaccine rollout. Food deliveries are provided to people who shouldn’t risk leaving their homes.

Spence says she’s learned a lot from calls federal bureaucrats organize with Manitoba First Nations leaders. They monitor trends and share suggestions on how to be safe.

She says it’s empowering to be able to collaborate with other chiefs. Instead of top-down messaging for First Nations to follow, it gives her the opportunity to hear about challenges that communities have overcome.

“I think people are pretty resilient,” she says.

● ● ●

The northwest corner of Manitoba has largely been spared COVID-19 cases, with less than 25 over the course of the pandemic.

In a sparsely populated region that borders Nunavut, residents are used to being isolated from the rest of Canada — but not from each other.

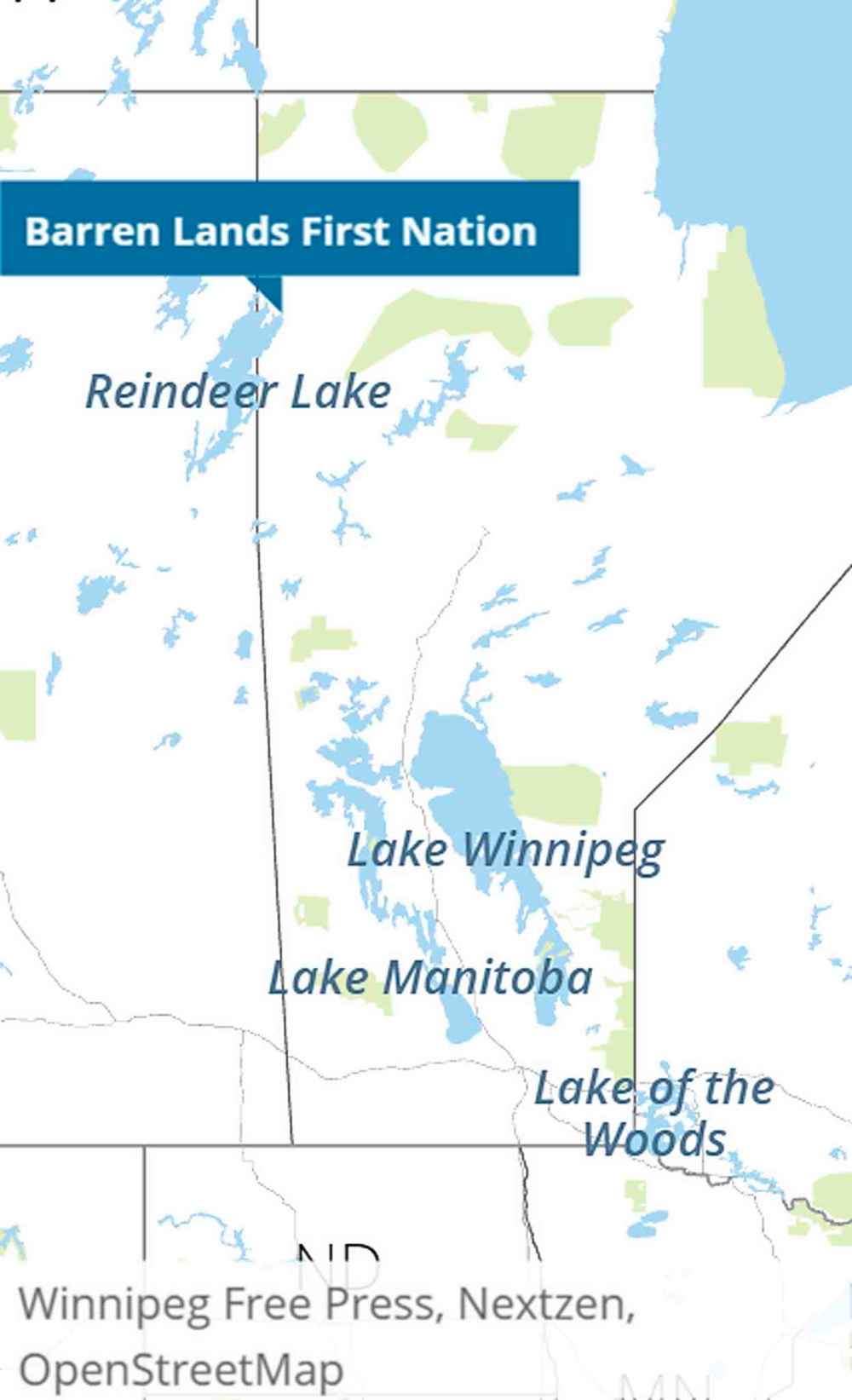

“It’s very hard, but we can do this if we follow the restrictions and the protocols,” Barren Lands Chief Trina Halkett says.

Her community of 500 sits 80 kilometres away from the nearest town, which can be reached by snowmobile.

In the summer, a barge travels 200 kilometres down Reindeer Lake to the nearest road in Southend, Sask. In the winter, ice roads link the community to the south.

Barren Lands’ most direct lifeline is a daily flight to Thompson that touches down in two other communities along the way; since the pandemic started, those flights have been reduced to three days a week.

Halkett’s community hasn’t faced a single COVID-19 case, thanks to the isolation and unrelenting sacrifices from its residents.

“I’m very honoured that the members are really taking every step for their safety,” she says.

Early in the pandemic, the band distributed large colour-coded signs for each house to display. People with red signs must isolate due to a possible COVID-19 exposure. Yellow signs are for people who have medical issues and must stay home and green signs are for those who can move freely.

Band staff routinely check whether yellow-sign homes need help — and if anyone with a red sign is breaking the rules.

There is also a large shelter, complete with bedrooms, a kitchen and laundry room, provided by the federal government to quarantine people returning from outside the community.

Most homes have a box for deliveries to be dropped off, whether it’s food from the grocery store or schoolwork for the kids.

Teachers are trying to stick with a system of delivering coursework on Mondays and collecting the completed packages on Fridays, with some classes online and some short lessons in class for only three or four students on a rotating basis, each lasting one or two hours.‘My siblings are in Lynn Lake, and I can’t see them…. I’m very concerned for them, where they’re at. But I do check up on them.’– Barren Lands Chief Trina Halkett

The grocery store closes every 90 minutes to disinfect high-touch surfaces. The nursing station requires appointments.

At the petroleum-tank terminal, workers continue to fly in to help replenish supplies and make upgrades. But even that process follows a detailed protocol to avoid close contact with anyone in the community.

The nearest outbreak is a 120-km journey by snowmobile to the small town of Lynn Lake, where approximately a third of the 500 residents have been infected.

Halkett says Lynn Lake RCMP work with local safety officers to help keep track of who has visited the community to make sure they’re isolating at home.

“My siblings are in Lynn Lake, and I can’t see them,” says Halkett, who relies on video calls.

“I’m very concerned for them, where they’re at. But I do check up on them.”

Winter roads will soon be open, with a short window for residents to get vehicles, construction supplies and other necessities for the year ahead. The band will have to balance the need for people to get what they need with the risk of introducing strangers into the community.

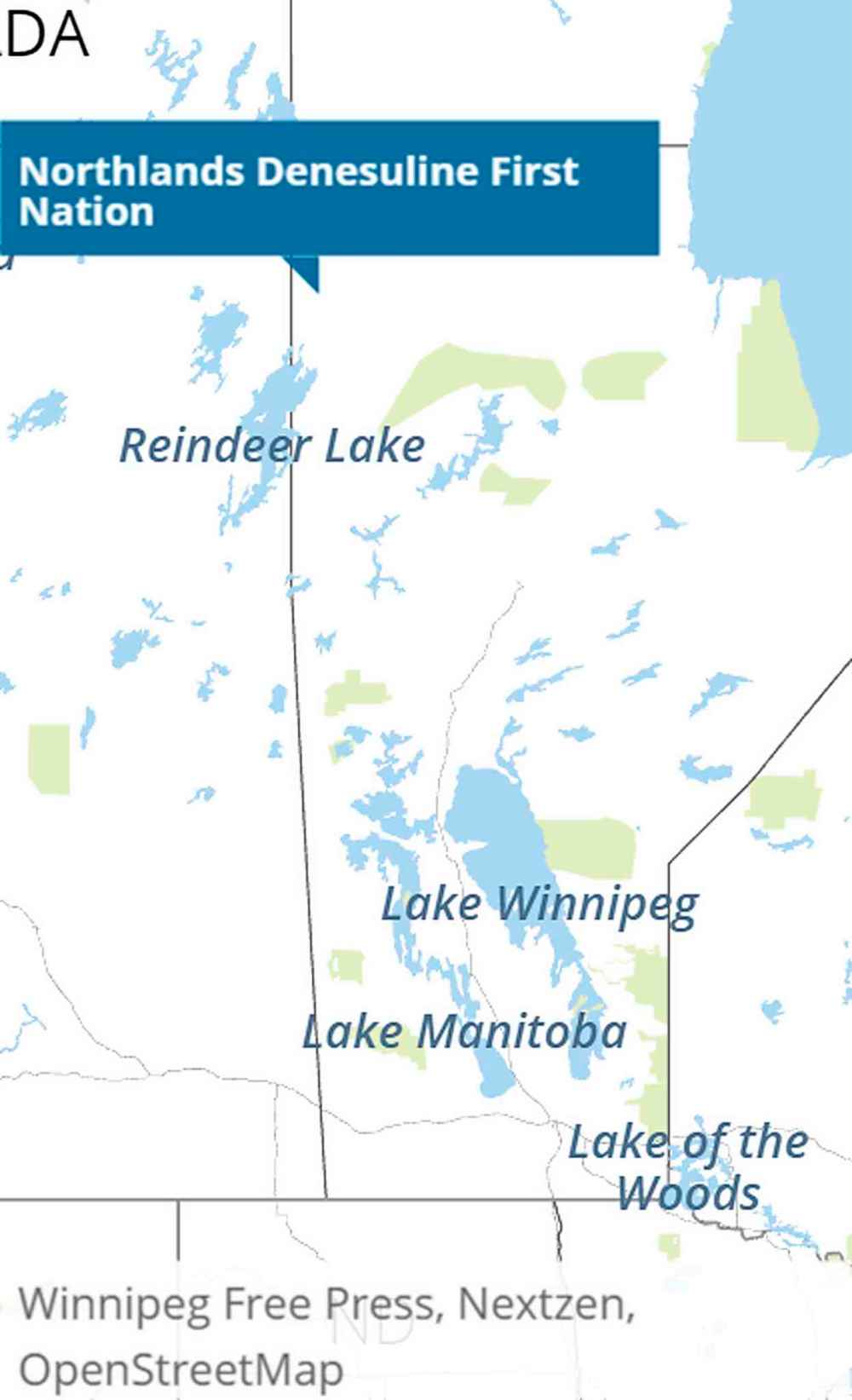

It’s a similar concern for nearby Northlands Denesuline First Nation.

Chief Simon Denechezhe lists many of the same protocols as Barren Lands for his community’s 957 residents. People entering the community have to have a negative COVID-19 test and isolate, sometimes using a housing shelter originally intended for visiting construction crews.

Both bands have doubled down on tapping into Dene culture to see them through the tough times.

“For the wellness of our community, we’ve got to keep their minds healthy,” Denechezhe says.

“It’s been a long time now that we’re in isolation, in a remote community.”

The bands are encouraging families to go hunting, trapping and fishing. That gets people moving and connected with the land, but it also helps secure healthy food.

“We ask the parents to go out on the land with them, and we purchase tools they need to be out on the land, even for a short period of time,” Denechezhe says.

Meanwhile, a Facebook page dedicated to events families can participate in from home has 1,600 members — almost everyone in the area, plus their cousins in Winnipeg.

A Halloween contest involved costumes and carving pumpkins.

Earlier this month, children were making craddleboards, the centuries-old device used to carry babies on one’s back, while adults joined in on making a cardboard display of dog-mushing.

Halkett hopes all Manitobans find ways to connect, and to get outside this winter.

“It must be very hard in the city; I can’t imagine what they go through. Being outdoors is mental and spiritual health.”

● ● ●

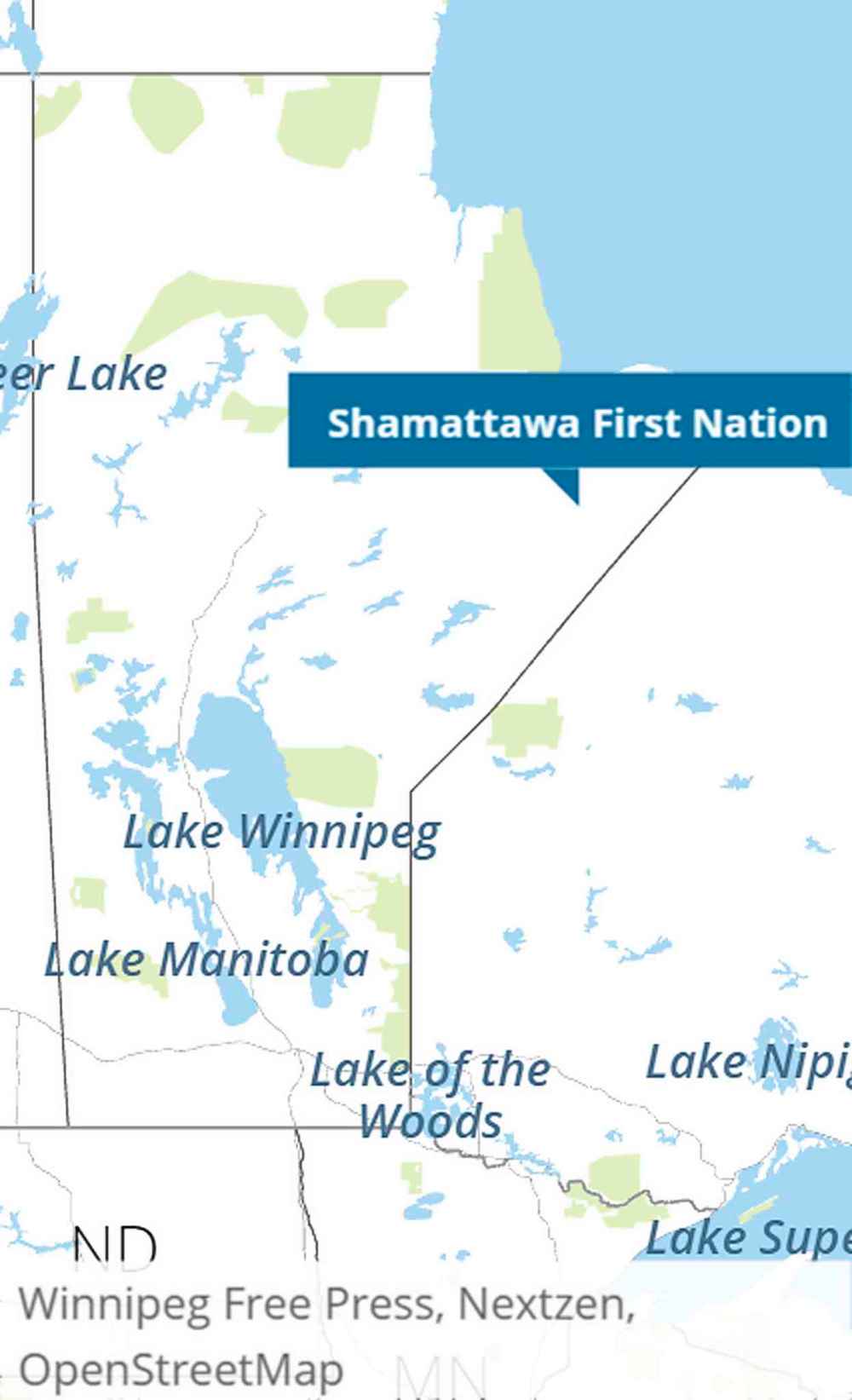

For months, Shamattawa, a remote community tucked into Manitoba’s northeastern flank, had no cases.

That all changed in mid-November, when a resident travelled to a Winnipeg hospital for issues unrelated to COVID-19.

By the time it was detected, a second person was infected. The community’s third case, a woman in her 60s, infected 14 others, including an infant, living under the same roof.

Within a month, one-third of the community of 1,468 was infected, and 75 per cent of tests were coming back positive.

Officially, 445 residents have had the virus as of earlier this week; all but three have recovered.

Yet the number of people who survived an infection is surely higher, insists Chief Eric Redhead, because the community never had enough testing.

Redhead warned last March his community lacked protective gear and testing capacity to control an outbreak.

Shamattawa is regularly studied by tuberculosis researchers, because the disease is so prevalent in a community where 15 people often live in a four-bedroom house.

Because of that, it was one of the first communities to get rapid COVID-19 testing after federal officials were able to rejig machines normally used for TB screening.

But those machines were overwhelmed in November, when dozens of elders had to be flown to Winnipeg to be closer to hospitals.

A First Nations pandemic-support team was similarly overloaded, and Redhead says federal officials mulled pulling nurses out of southern reserves to go help control the coronavirus in the North.

The Assembly of First Nations sounded the alarm about one of the worst outbreaks in Canada, prompting a military deployment.

“It all comes from overcrowded homes, with asymptomatic people going about their business,” Redhead says.

“I feel like a broken record; I keep saying that over and over — but it’s true.”

Redhead, 34, grew up in a house where water came from buckets dipped into a river through a hole carved into the ice. His family got running water when he was 14, around 2000.

“Being able to wash your hands with running water was just amazing,” he says.

The Indian Act essentially forbids home ownership, making it complicated to obtain a mortgage. Bands can rarely afford to build anything that isn’t a modular home, and the over-capacity buildings quickly rack up wear and tear, Redhead says.

And comparatively high birth rates — about 50 babies are born each year at Shamattawa — make years-long waiting lists swell.‘If there’s another pandemic, we’re going to be hit hard unless we really address the root cause of the spread, and that’s overcrowding in homes.’– Shamattawa Chief Eric Redhead

“The system is set up against us, and I don’t think most Canadians understand that,” he says.

Gatherings also fuelled spread, made worse by the housing situation.

“If here’s another pandemic, we’re going to be hit hard unless we really address the root cause of the spread, and that’s overcrowding in homes,” he says.

Redhead says every community in Canada has people who don’t follow the rules, but in Shamattawa people complied to a greater extent when local medical staff took to the radio instead of dropping off pamphlets or having elected councillors do interviews.

Redhead says he’s thankful that the military, Red Cross and Bear Clan Patrol lent a hand to his community.

Only a month ago, he had harsh criticism for the sluggish response; it took weeks for the military and First Nations support teams to arrive.

“Looking back, a bit calmer, they didn’t have anything to draw on,” he says now.

But he’s critical of how the provincial and federal governments prepared for what happened in the fall.

“With the first wave of the virus, they had a really good chunk of time where they could have prepared themselves,” he says, adding it’s a miracle nobody died from COVID-19 in Shamattawa.

“I think they dropped the ball.”

● ● ●

On paper, Sioux Valley Dakota Nation is a prime spot for COVID-19 spread.

The reserve is located just north of the Trans-Canada Highway about 50 kilometres west of Brandon, and families have ties to numerous communities across the Prairies.

The reserve operates a Petro-Canada station that attracts strangers travelling through, and faces the same factors that have allowed COVID-19 to wreak havoc on other First Nations, such as overcrowded housing and medical conditions including diabetes and asthma.

Yet the community of 1,500 did not have a single case in 2020, even during outbreaks in Brandon and on nearby Hutterite colonies.

“We had our plan in place, and knew what to do,” Chief Jennifer Bone says.

However, she stresses it’s still too early to declare victory.

Sioux Valley has kept its schools closed since March and implemented a mandatory quarantine on anyone who left the province, even though the Saskatchewan border is only 70 kilometres away.

“Clear, consistent messaging” to stay home and not hold gatherings avoided confusion, Bone says.

The band leveraged social media to provide regular updates through smartphones, an option that didn’t exist during the H1N1 swine flu pandemic in 2009.

In the wake of that pandemic, the community updated its emergency plan so it was ready in March to isolate and care for people.

The local gas station, at the crossroads of the Trans-Canada and Highway 21, has staff on the pumps filling customers’ vehicles to avoid close contact. The store limits how many people can be inside at one time.

Christopher Hersak, the First Nation’s incident commander, says the idea was to limit contamination as much as realistically possible.

“We don’t have a dome to go over our community,” Hersak says. “We’re not giving up our energies anytime soon.”

Sioux Valley’s first case emerged Jan. 11, after someone attended a Dec. 30 funeral at a home in the community.

Two weeks later, there were 33 infections and 92 people isolating.

Just this week, a worker at the personal-care home tested positive, prompting the community to establish checkpoints and roadblocks.

But by that point, each of the home’s residents had already received their first dose of the Moderna vaccine, which should prevent the worst outcomes.

That’s a safety blanket few other communities in Manitoba can claim, but it’s come at a cost.

The First Nation runs a huge winter festival in Brandon at this time of year that had to be cancelled in October.

Powwows and sweat lodges have all been cancelled, while elders are reminding locals about traditional teas and medicines that can boost their physical and mental health.

“We just really encourage people to keep that up in their homes,” Bone says.

The community declared a state of emergency last fall due to four suicides. Bone says it’s clear the lockdown is impacting mental health.

Leaders are thankful for federal support, both in the immediate aftermath of those deaths, and the more recent support to keep COVID-19 cases low.

“Even though pandemics have a tendency to exacerbate the health inequities, it often brings out the best in people too, and that is the spirits of helping other people,” Hersak says.

“It’s been a test of resiliency itself.”

Residents draw upon inspiration from the buffalo, which is spiritually important in Dakota culture.

In recent years, seven white buffalo have been born in the reserve’s compound, a rare occurrence that traditionally signifies change.

Bone says people visit the site to pray for the strength to get through this period of change, and to remind themselves of what Dakota have achieved over the centuries.

“Our people really look to that for their strength, for their courage,” she says.

● ● ●

With 10,600 members, including 3,600 on reserve, Peguis First Nation is large enough to have its own subculture of Internet memes.

The latest is an image of two professional wrestlers, with their faces replaced by those of Chief Glenn Hudson and Premier Brian Pallister; they have repeatedly sparred over how to keep COVID-19 cases at bay.

With cramped housing and limited access to health care, Hudson says the only real option to prevent outbreaks is aggressively targeting each case early on.

“We need to continue to stay on top, and monitor these things, so that we have the best outcomes,” Hudson says.

In April, the First Nation established a curfew and checkpoints, screening out anyone who doesn’t live in the community or on nearby reserves. The thousands of band members living in Winnipeg were forbidden to visit, unless they were on essential business.

Restrictions loosened over the summer as Manitoba’s daily case count trickled down to single digits, but resumed when provincial cases numbers surged in the fall.

The community hired contact-tracing staff and leaned on Ottawa to get extra testing capacity.

People driving off the reserve had to seek permission for specific tasks and had to register their mileage upon leaving and returning, to ensure they were making only essential trips.

Over the holidays, as case counts got under control, Hudson allowed “relaxed lockdown” days, where families could visit one home on the reserve, and that Peguis household then had to isolate for four days.

Hudson says this was a reward for keeping spread under control, and a sign of trust.

“Each of us has a responsibility to one another to keep our communities safe,” he says.

Yet the holiday exemptions flouted a provincial order against non-essential visits.

Pallister decried the community’s measures as a “massive mistake,” and urged Ottawa to intervene, since reserves are federally regulated. But Hudson says the top-down, colonial approach has never worked well in the past.

After Christmas, the reserve registered no new cases for 26 days, until a single person returning from Winnipeg brought the virus.

That case has been linked to 12 infections, as of Tuesday, all of whom are relatives from three households. Hudson says a minority of rule-breakers can create chaos in communities with cramped housing.

Hudson notes his reserve implemented a mandatory quarantine period for anyone who travelled outside of Manitoba about 10 months before the Pallister government did.

And while some of the premier’s comments have prompted accusations of racism, the Pallister government is getting accolades for putting First Nations in charge of their COVID-19 response.

The First Nations Pandemic Response Coordination Team is administering Moderna doses on reserves, analyzing and distributing data collected by the province’s public-health nurses, deploying support teams to outbreaks and shaping their own messaging around prevention and vaccines.

That’s a complete opposite of the H1N1 swine flu in 2009, which disproportionally hit First Nations and was managed with a top-down process led by Ottawa.

Hudson says he hopes the work of the response team along with bands like his own will convince Manitobans to give more power to First Nations when the pandemic subsides.

Before the pandemic, bands and tribal councils launched small-scale projects aimed to shift health-care services into local hands.

Many hope to fully control health services in their communities, to give good jobs to residents and provide care from people with the same cultural background.

Hudson sees that as part of a movement of drawing down authority over education and child welfare, instead of being ruled by the Indian Act.

“We are breaking out of that process, and that is something we are taking step by step,” he says, linking it back to the decisions around holiday gatherings.

“We have an inherent right to look after our community, and make decisions surrounding that right.”

dylan.robertson@freepress.mb.ca