Easy to judge, difficult to escape

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 22/10/2011 (5164 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

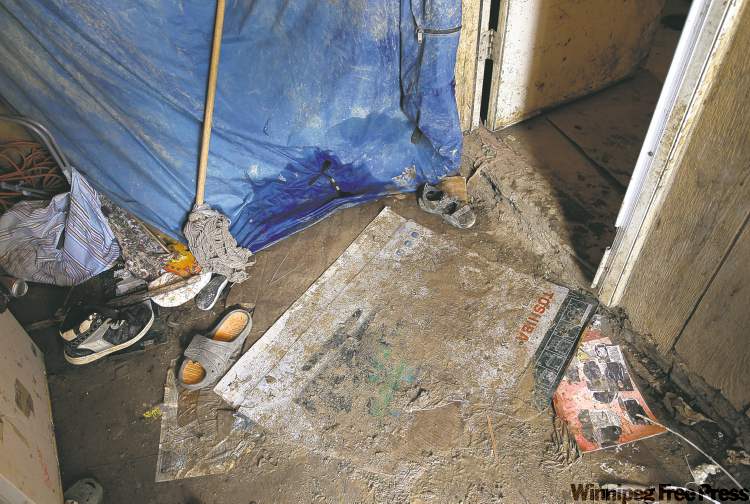

When we stepped into Richard Andrews’ home in Wasagamack, we had only one question: Why the hell are you living here?

For Free Press photojournalist Joe Bryksa, who has visited two dozen homes without running water all across this province, it was the worst he’d seen. Dirty clothes piled everywhere, floors gritty with mud, window frames crusted with mould. Most walls were covered with scribbles, and every piece of furniture looked like something left beside a dumpster.

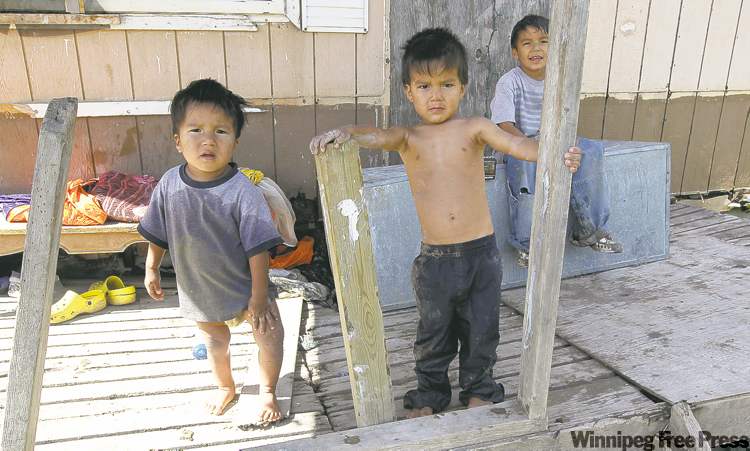

There are six adults and seven kids under the age of nine who live, off-and-on, in the old trailer, with no indoor toilet or running water. A few of the toddlers were so caked with mud I, to my own shame, paused for a second before lifting one up to help him onto a rickety porch in a yard strewn with garbage.

Why would anyone allow their children to live in a home like this? Why not pay for a water tank or a septic field? Or find another house? Or move to Winnipeg? Or Thompson?

These are questions readers asked of other families following our original, three-part series No Running Water, produced last year by Bryksa and assistant city editor Helen Fallding.

They are fair questions.

University of Manitoba psychology professor Katherine Starzyk, who is about to begin a research project on the North’s water woes, says most people are conditioned to believe they live in a fair and just society, that their government is fundamentally good. When we’re confronted with the opposite, we tend to rationalize, to downplay, to blame the victim. Our government wouldn’t allow 1,400 Manitobans to live in Third World conditions, so it must be their fault, we think.

Some families have the time, energy and money to create a reasonable life without proper running water. When the late Zach Harper, an elder, was staying with his daughter-in-law while he waited for a new house with proper water, we dropped by to visit the frail, old gentleman. His daughter-in-law’s bungalow was pristine. New laminate flooring was being installed in the living room, and there was not one speck of dirt on it. The kitchen was almost spartanly tidy.

Only later did someone tell us Harper’s daughter-in-law also has no indoor plumbing. But, unlike the Andrews family, she lives close to the lake and uses lake water for housecleaning. And her home is not jammed to the rafters with kids and extended-family members.

We also met people like the Taylors, profiled this weekend. Alice Taylor is among the most articulate, organized and upbeat members of this community. She is a vocal advocate for her son, who has cerebral palsy. The family also has no running water, but, for whatever reason, they have the resources to raise a little hell on their son’s behalf.

But there is also the grinding daily reality of poverty. If you have chronic diarrhea from drinking unclean water, it’s difficult to find the energy to lug buckets of water up from the lake or the communal tap to clean house. Do you wash the walls or do you use your pail of water for drinking?

If you’ve spent another uncomfortable night on a mattress in the living room in a house with 14 other people, you might not feel like labouring away at an old ringer washing machine to plow through piles of dirty clothes.

If your trailer’s walls are so papery they’ll melt if you try to scrub off the graffiti, it’s better not to try.

In a community with road access for only about a month of the year, it’s not possible to nip out to Rona, so supplies such as new linoleum, a can of paint or some drywall are hard to come by, even if you have the money to afford them.

While we were visiting Andrews’ family, we saw one kid, the goofball of the group, pour dish soap on his head as a joke while playing in the yard. Most moms would grab that kid and toss him in the tub. What do you do when you have no tub?

As Dr. Bruce Martin, the former director of the University of Manitoba’s northern medical unit, told Helen Fallding last year, spending hours a day hauling water steals time from more meaningful activities such as looking after your kids.

But there is also a sense of lethargy that grips some people in northern communities — a learned helplessness that comes from generations of poverty, the legacy of residential schools and dependence on fickle band councils and Ottawa, which traditionally does the bare minimum when it comes to housing, education, health and infrastructure. No one else really notices the effect of that because few outsiders visit remote reserves.

When we visited Island Lake in August, we asked several families when they thought they might get a new house, when they last lobbied their band councillor, where they stand on the priority list for a house. The answers were often the same. They didn’t really know. All they could do is wait.

We asked Richard Andrews why he doesn’t finagle a better house in the community.

“I don’t know where I’d stay if I moved from here,” he answered. “I don’t know, I guess there’s no houses.”

That’s an understatement. Wasagamack has about 250 houses, mostly two or three-bedroom bungalows, bi-levels or trailers, with an average of seven occupants per home. Many are as awful as Andrews’. If the band were to strive for more Winnipeg-like occupancy rates — four people per house — they’d need nearly twice the number of homes. There really is no place to go.

So why doesn’t Andrews move to Winnipeg? That’s not a question we’d ask someone from Dauphin or Morris. There, we’d just expect homes to have running water. And it dismisses the genuine connection aboriginal people have to their land, a connection consecrated in treaties with Ottawa that are more than 100 years old, treaties that guarantee the right to clean water.

“I like staying here, in my community,” said Andrews. “I just like it here. It’s a good place to stay.”

maryagnes.welch@freepress.mb.ca