Misery and indifference

It's been a year since the Free Press turned a spotlight on the lack of running water on Manitoba reserves. Desperate residents are still waiting for rescue from Third World conditions

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 22/10/2011 (5164 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

WASAGAMACK — Richard Andrews is a man of few words and a fan of understatement.

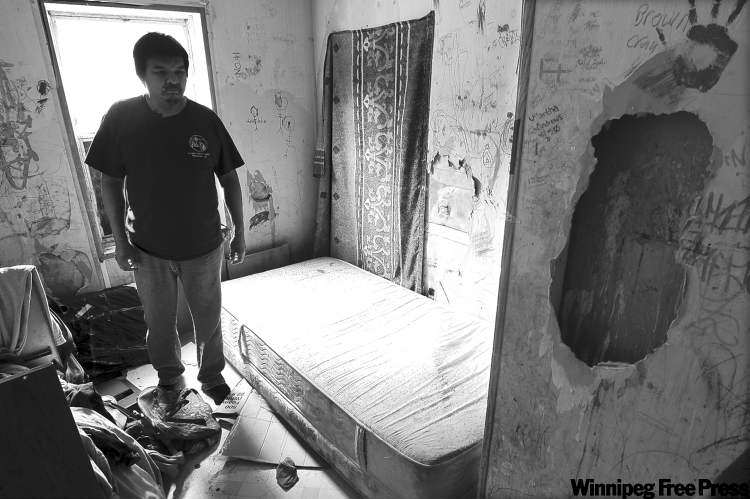

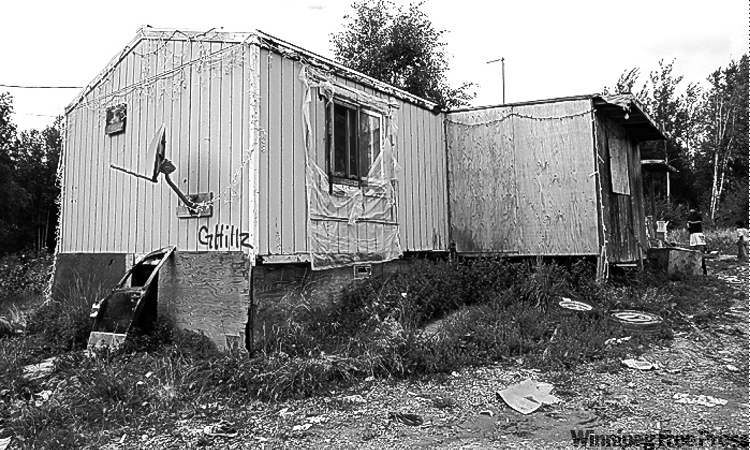

Standing in the gloom of his sagging trailer, he surveys the muddy floor, the goopy flypaper dangling from the kitchen ceiling, the piles of dirty clothes and the dishes stacked in a sink with no faucet. Graffiti and children’s scribbles cover what remains of the walls, around holes that allow pink insulation to peek out. It’s freezing in the winter, mouldy when the furnace kicks in and worse than even the slummiest apartment in Winnipeg.

“This place should be condemned already,” Andrews says with a shrug.

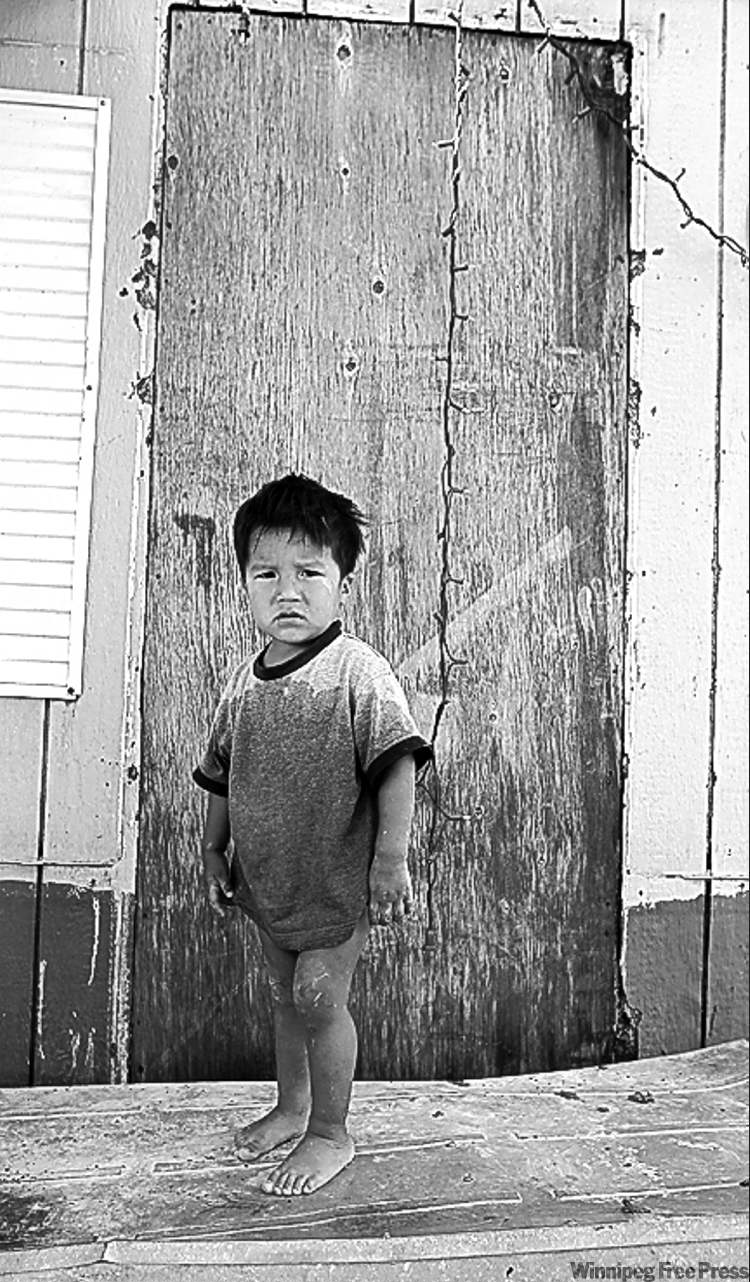

Andrews lives, often with five other adults and his seven or eight grandchildren in what is likely the most squalid home on the reserve with the most pressing sanitation problems in the province. There is no running water to wash clothes, bathe the gaggle of muddy toddlers, do dishes or keep the floors clean. The family shares a slop pail, lined with a garbage bag, in what passes for a bathroom.

In Wasagamack, more than 60 per cent of homes have no indoor plumbing, not even a cistern filled up weekly by a water truck or a sewage holding tank that gets pumped out by a honey wagon. Access to clean drinking water and real toilets is a fend-for-yourself hodgepodge of old plastic water tanks, long walks to communal taps that become ice-mountains in the winter, water trucks that break down and slop buckets dumped on garbage piles behind homes.

Getting proper drinking water can sometimes consume hours of a family’s time.

Only about 90 homes on the reserve have piped water and sewer services of the kind Winnipeggers rarely think twice about.

The four Island Lake reserves are all in the same predicament, but Garden Hill, Red Sucker Lake and St. Theresa Point have a slightly higher proportion of homes with running water and working toilets.

In all, 1,400 homes on First Nations reserves in Manitoba have no indoor plumbing, and most of those are in Island Lake.

Many families get by on less than 15 litres of treated water a day — imagine four, four-litre milks jugs of water to cook with, drink, brush your teeth, maintain basic personal hygiene. That’s less than United Nations’ aid workers recommend for disaster victims. The average Winnipegger uses 20 times that much each day.

The lack of running water on reserves contributes to remarkably high rates of skin rashes, superbug infections and flu outbreaks that often mean frequent trips to the nursing station or even medevacs to Winnipeg. One of Andrews’ grandsons has been sent to Winnipeg several times with respiratory problems. Those ailments don’t include frequent bouts of diarrhea, stomach cramps and vomiting that are accepted as regular occurrences in homes without clean running water.

This is not news.

It’s been a year since the Winnipeg Free Press shone a light on the lack of running water in many homes on the four reserves and then, with other media, forced the issue of northern sanitation onto the national agenda.

Since then, students marched to the legislature, politicians such as former Liberal leader Michael Ignatieff made it a federal election issue, native leaders sent a lobbying delegation to Ottawa and even visited Pope Benedict XVI about the problem.

There have been postcard campaigns, public meetings, a damning national assessment of existing water and sewage treatment plans and yet another report by Canada’s auditor general condemning the dismal state of on-reserve sanitation.

Premier Greg Selinger, under pressure from Manitoba’s native leaders to pick up Ottawa’s slack, raised the water crisis at a meeting of the country’s premiers in July.

Despite all that, virtually nothing has changed in Island Lake.

There has been little progress bringing modern services to the 800 homes without them. Only a handful of houses — about 30 in St. Theresa Point and another 14 in Wasagamack — were built or retrofitted over the summer so families without sinks and toilets can finally have them.

And, Ottawa spent $1 million earlier this year on 1,000 new water barrels and latrine pails — conveniently equipped with toilet seats. The water tanks and slop pails were distributed in the four Island Lake communities, but aboriginal leaders say they added insult to injury and suggested Ottawa was unlikely to solve the problem any time soon.

Ottawa also sent a new water truck and a new sewage truck to each of the communities but did not offer funding to hire operators, pay for gas or winter garages.

The Island Lake bands originally asked for $8 million for emergency aid, and came up with the creative idea of campground-style central laundry and shower facilities that could be built quickly over the summer as a stop-gap measure. Those never materialized.

There has been no commitment from Ottawa to fast-track the construction of more pipes or treatment plants or to retrofit homes with cisterns, which are cheaper and simpler to install but not as reliable.

No one can say when all 1,400 Manitobans without running water will get it.

That leaves Richard Andrews in limbo.

“I don’t know,” he says when asked when he might get a new house with indoor plumbing.

“I don’t know. I’m just waiting.”

Roughly 13 people live in his trailer on and off, including seven of his grandchildren under the age of nine. They spent one August afternoon playing on a rickety, muddy porch out front while their parents went to the Northern Store to get groceries.

About five of the children recently went to live temporarily with their parents in another unit on the reserve, but the family expected to get kicked out this fall and planned to return to Andrews’ home.

Wasagamack Chief Alex McDougall said there is some hope on the horizon for the family. Because of the home’s extreme overcrowding, the band is expected to earmark a new home for some of the family members. The band recently used insurance money to rebuild a home that burned down on the reserve, and that unit will likely be given to one of Andrew’s grown children. That will reduce the overcrowding in his trailer, but it won’t solve his water problem.

Andrews’ trailer, which was meant to be a temporary solution a decade ago, isn’t very close to the lake, so it’s tricky to haul buckets of lake water to wash the floors, counters and walls as many families do. At this point, washing the papery walls would only make the trailer disintegrate.

His kids and grandkids have used lighters to burn black graffiti into the stippled, plaster ceiling in all three bedrooms and oddities of trash — empty chip bags, a Pampers diaper, a rusty old curling iron, crumpled Christmas wrapping — is strewn on the filthy floors. The combination of overcrowding and the lack of proper sanitation has rendered his home a lost cause.

“I need a new house, to build a new house,” he says.

maryagnes.welch@freepress.mb.ca