Biden’s pot pardon is a preferable approach

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/10/2022 (1152 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The 250,000 or so Canadians who are still deemed cannabis criminals likely took note last week when U.S. President Joe Biden pardoned Americans who had been convicted at the federal level of possessing recreational cannabis. It would be understandable if the Canadians asked: if the U.S. did it, why doesn’t Canada?

Given the legal status of recreational cannabis in the two countries, it might be expected Canada would outpace the U.S. in the pardon process. In the U.S., possession remains illegal in most states. In cannabis-friendly Canada, where the drug has been legal since Oct. 17, 2018, and retail outlets are common, a pardon application system that started in 2019 can fairly be considered a flop, as only a few hundred Canadians have successfully negotiated the complex and expensive procedure.

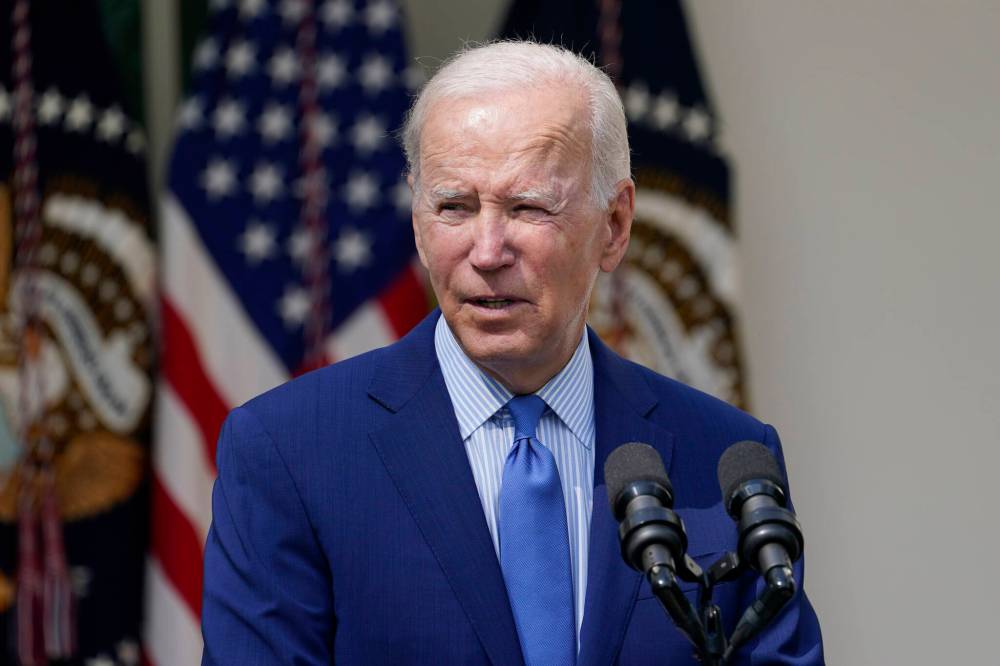

Susan Walsh / Associated Press files U.S. President Joe Biden

That means Canadians busted in the bad old days for possession of cannabis still carry the substantial burden of a criminal record that can be a deal-breaker when applying for a job, travelling outside the country or volunteering within the community.

Fortunately for these Canadians, help appears to be on the way in the form of an amendment to a bill that was passed by the House of Commons during the summer and is currently being studied by the Senate. The intent of the amendment is that Canadians with criminal records for simple drug possession will see their records disappear within two years.

The relevant section of Bill C-5, also known as the criminal justice reform bill, calls for the automatic “sequestration” of drug-possession records, which means the offence won’t be revealed on criminal-record checks. The change is intended to be a more practical alternative to the current pardoning process in Canada, which can involve many bureaucratic hurdles to update various police and court records.

Credit belongs to the New Democratic Party for this progressive effort to free cannabis convicts from the lifelong consequences that have plagued them since they were arrested. It was NDP justice critic Randall Garrison who proposed the amendment, which was accepted by the ruling Liberals.

“I said we needed a better bill. … Highest on my list was trying to get rid of criminal records for simple possession,” he told the Toronto Star.

The Liberal bill successfully amended by the NDP is far-reaching. It ends mandatory minimum sentences for all drug offences, lets police and prosecutors use their discretion to keep drug possession cases out of the courts and encourages conditional sentences.

A laudable intent of the bill is to reduce the over-incarceration of Indigenous and Black people in prisons, an issue of considerable importance in Manitoba, which has the highest per-capita population of Indigenous people in Canada and where about 75 per cent of incarcerated adults are Indigenous.

Of the 94 calls to action in the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 12 deal directly with the criminal justice system and how it serves (or fails to serve) Indigenous people. Calls include alternatives to imprisonment for Indigenous offenders and amendments to the Criminal Code to let judges to depart from mandatory minimums.

The response to such reconciliation calls are reflected in the criminal-justice reforms outlined in the bill currently winding through the political process. The changes are overdue, and will be welcomed by many people, including those Canadians eager to escape the burden of criminal records for possession of a drug that, after all, is now as legal as tobacco or alcohol.