Church’s apology must come from the top

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 04/10/2021 (1614 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

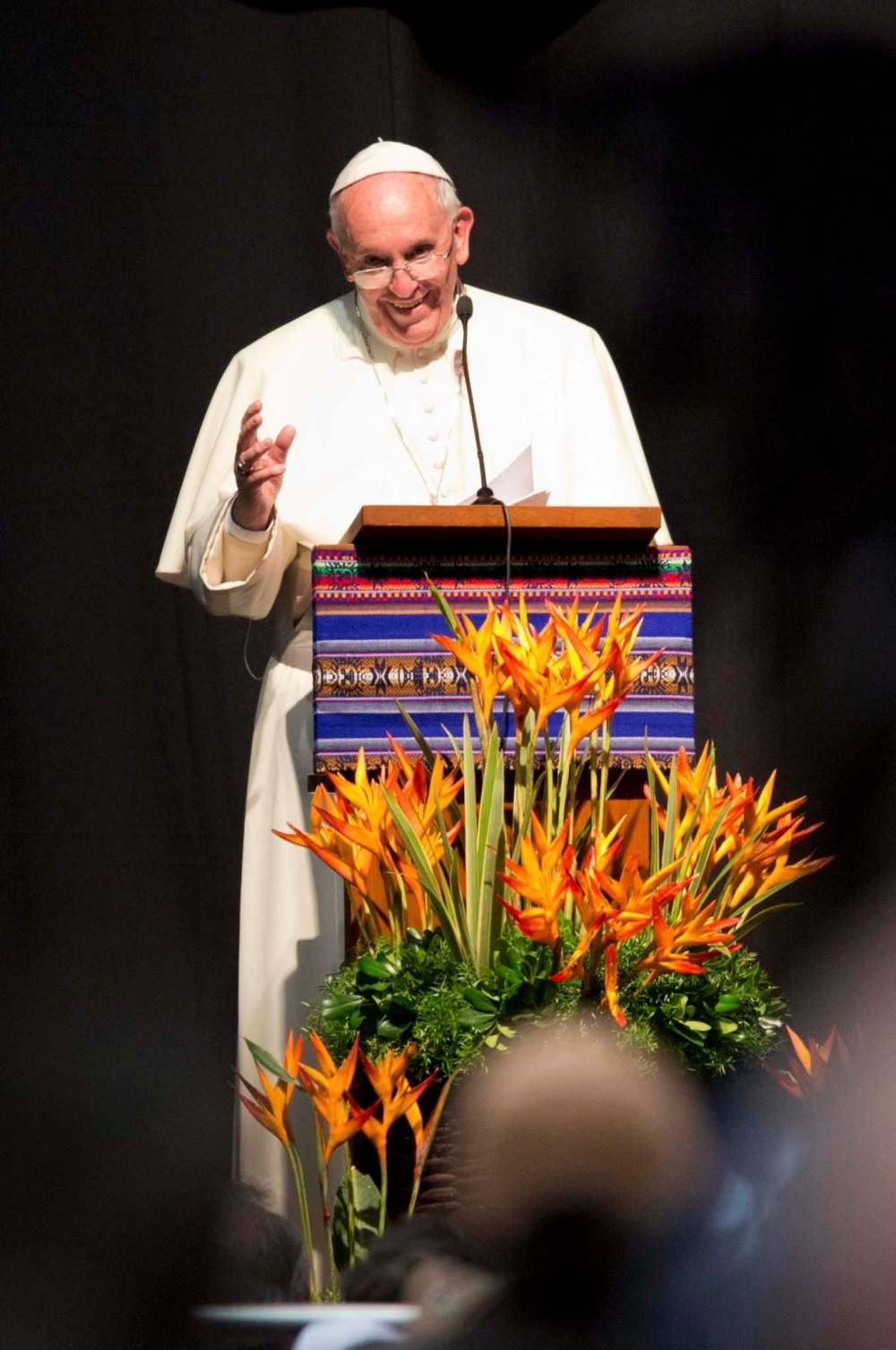

In 2015, Pope Francis delivered a powerful apology in Bolivia, humbly begging forgiveness for the sins and crimes committed by the Roman Catholic Church against Indigenous peoples.

“I would also say, and here I wish to be quite clear, as was St. John Paul II: I humbly ask forgiveness, not only for the offences of the church herself, but also for crimes committed against the native peoples during the so-called conquest of America,” history’s first Latin American pope told a summit of Indigenous groups and activists.

In 2018, the pontiff issued a sweeping apology at Dublin’s Phoenix Park, to children who were forcibly taken at birth from their homes. Ireland has thousands of now-adult adoptees who were seized from their mothers, women who after becoming pregnant out of wedlock had been forced to live and work in laundries and other workhouses for “fallen women.”

“May the Lord keep this state of shame and compunction and give us strength so this never happens again, and that there is justice,” the pope told a mass attended by 130,000 in the first papal visit to Ireland in almost 40 years.

Clearly, there is ample precedent for Pope Francis to do exactly what Indigenous leaders and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau have been seeking for years — deliver a full-throated apology on Canadian soil for the atrocities committed at church-run residential schools.

In the same year as the pontiff’s Bolivia visit, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission issued 94 calls to action, with No. 58 demanding the Pope apologize to survivors, their families and their communities for the church’s role “in the spiritual, cultural, emotional, physical, and sexual abuse of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis children in Catholic-run residential schools.” The TRC’s position is that an apology in Rome is not sufficient; it has to be made in Canada, where the harm was done.

In 2017, the prime minister met privately with the Pope at the Vatican and afterward stated, “I then told him about how important it is for Canadians that we move forward on a real reconciliation with Indigenous peoples and highlighted how he could help by issuing an apology.”

Calls for a papal apology have intensified since revelations regarding unmarked graves on the grounds of former residential schools earlier this year — beginning in May when ground-penetrating radar identified what is believed to be the remains of 215 children buried at the former Catholic-run residential school in Kamloops, B.C.The bishops’ apology is an important first step, but it falls far short of what is needed, and what has been requested.

Late last month, days ahead of the first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, Canada’s Roman Catholic bishops took a bold step by “unequivocally” apologizing to Indigenous people for the horrors of Canada’s residential school system.

Along with acknowledging “the grave abuses that were committed by some members of our Catholic community; physical, psychological, emotional, spiritual, cultural, and sexual,” the bishops pledged to work with Indigenous people toward arranging a long-sought papal visit.

The bishops’ apology is an important first step, but it falls far short of what is needed, and what has been requested. Their action does not free the Pope from an obligation to apologize; in fact, it heightens the pressure because it makes clear the church understands, and accepts, the anguish it inflicted on Indigenous people.

It is long past time for an apology from the man who is the head of the worldwide Catholic church and the Vatican City State. History shows the pope has been willing to do the right thing in the past; if there is to be true reconciliation in this country, he must find the grace to do it again.